Lyrebird

| Lyrebird Temporal range: Early Miocene to present | |

|---|---|

| |

| Superb lyrebird | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Suborder: | Passeri |

| Family: | Menuridae Lesson, 1828 |

| Genus: | Menura Latham, 1801 |

| Species | |

A lyrebird is either of two species of ground-dwelling Australian birds, that form the genus, Menura, and the family Menuridae. They are most notable for their superb ability to mimic natural and artificial sounds from their environment. As well as their extraordinary mimicking ability, lyrebirds are notable because of the striking beauty of the male bird's huge tail when it is fanned out in display; and also because of their courtship display. Lyrebirds have unique plumes of neutral-coloured tailfeathers and are among Australia's best-known native birds.

Taxonomy and systematics

The classification of lyrebirds was the subject of much debate after the first specimens reached European scientists after 1798. The superb lyrebird was first illustrated and described scientifically as Menura superba by Major-General Thomas Davies in 1800 to the Linnean Society of London.[1][2] He based his work on specimens sent from New South Wales to England.

Lyrebirds were thought to be Galliformes like the broadly similar looking partridge, junglefowl, and pheasants that Europeans were familiar with, and this was reflected in the early names the superb lyrebird had, including native pheasant. They were also called peacock-wrens and Australian birds-of-paradise. The idea that they were related to the pheasants was abandoned when the first chicks, which are altricial, were described. They were not placed with the passerines until a paper was published in 1840, 12 years after they were first placed in their own family, Menuridae. Within that family they are placed in a single genus, Menura.[3]

It is generally accepted that the lyrebird family is most closely related to the scrub-birds (Atrichornithidae) and some authorities combine both in a single family, but evidence that they are also related to the bowerbirds remains controversial.[4]

Lyrebirds are ancient Australian animals: the Australian Museum has fossils of lyrebirds dating back to about 15 million years ago.[5] The prehistoric Menura tyawanoides has been described from Early Miocene fossils found at the famous Riversleigh site.[6]

Species

There are two extant species of lyrebird:

- Superb lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae), called weringerong, woorail, and bulln-bulln in Aboriginal languages.[7]

- Albert's lyrebird (Menura alberti), was named in honour of Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria.

Description

The lyrebirds are large passerine birds, amongst the largest in the order. They are ground living birds with strong legs and feet and short rounded wings. They are generally poor fliers and rarely take to the air except for periods of downhill gliding.[3] The superb lyrebird is the larger of the two species. Females are 74–84 cm long, and the males are a larger 80–98 cm long—making them the third-largest passerine bird after the thick-billed raven and the common raven. Albert's lyrebird is slightly smaller at a maximum of 90 cm (male) and 84 cm (female) (around 30–35 inches) They have smaller, less spectacular lyrate feathers than the superb lyrebird, but are otherwise similar.

Distribution and habitat

The superb lyrebird is found in areas of rainforest in Victoria, New South Wales and south-east Queensland, as well as in Tasmania where it was introduced in the 19th century. Many superb lyrebirds live in the Dandenong Ranges National Park and Kinglake National Park around Melbourne, the Royal National Park and Illawarra region south of Sydney and in many other parks along the east coast of Australia as well as non protected bushland. Albert's lyrebird is found in only a very small area of Southern Queensland rainforest.

Behaviour and ecology

Lyrebirds are shy and difficult to approach, particularly the Albert's lyrebird, which means that there is little information about its behaviour. When lyrebirds detect potential danger they will pause and scan their surroundings, then give an alarm call. Having done so, they will either flee the vicinity on foot, or seek cover and freeze.[3] Also, firefighters sheltering in mine shafts during bushfires have been joined by lyrebirds.[8]

Diet and feeding

Lyrebirds feed on the ground and as individuals. A range of invertebrate prey is taken, including insects such as cockroaches, beetles (both adults and larvae), earwigs, fly larvae, and the adults and larvae of moths. Other prey taken includes centipedes, spiders, earthworms. Less commonly taken prey includes stick insects, bugs, amphipods, lizards, frogs and occasionally, seeds. They find food by scratching with their feet through the leaf-litter.[3]

Breeding

The breeding cycle of the lyrebirds is long, and lyrebirds are long-lived birds, capable of living up to thirty years. They also start breeding later in life than other passerine birds. Female superb lyrebirds start breeding at the age of five or six, and males at the age of six to eight. Males defend territories from other males, and these territories may contain the breeding territories of up to eight females. Within the male territories, the males create or use display platforms; in the case of the superb lyrebird, it is a mound of bare soil; in the Albert's lyrebird it is simply a pile of twigs on the forest floor.[3]

Male lyrebirds call mostly during winter, when they construct and maintain an open arena-mound in dense bush, on which they sing and dance in courtship, to display to potential mates, of which the male lyrebird has several. The female builds an untidy nest, usually low to the ground in a moist gully, where she lays a single egg. She is the sole parent who incubates the egg over 50 days until it hatches, and she is also the sole carer of the lyrebird chick.

Vocalizations and mimicry

A lyrebird's song is one of the more distinctive aspects of its behavioural biology. Lyrebirds sing throughout the year, but the peak of the breeding season, from June to August, is when they sing with the most intensity. During this peak they may sing for four hours of the day, almost half the hours of daylight. The song of the superb lyrebird is a mixture of seven elements of its own song and any number of other mimicked songs and noises. The lyrebird's syrinx is the most complexly-muscled of the Passerines (songbirds), giving the lyrebird extraordinary ability, unmatched in vocal repertoire and mimicry. Lyrebirds render with great fidelity the individual songs of other birds and the chatter of flocks of birds, and also mimic other animals such as koalas and dingoes.[3] The lyrebird is capable of imitating almost any sound and they have been recorded mimicking human sounds such as a mill whistle, a cross-cut saw, chainsaws,[9] car engines and car alarms, fire alarms, rifle-shots, camera shutters, dogs barking, crying babies, music, mobile phone ring tones, and even the human voice. However, while the mimicry of human noises is widely reported, the extent to which it happens is exaggerated and the phenomenon is quite unusual.[3]

The superb lyrebird's mimicked calls are learned from the local environment, including from other superb lyrebirds. An instructive example of this is the population of superb lyrebirds in Tasmania, which have retained the calls of species not native to Tasmania in their repertoire, but have also added some local Tasmanian endemic bird noises. It takes young birds about a year to perfect their mimicked repertoire. The female lyrebirds of both species are also mimics, and will sing on occasion but the females do so with less skill than the males.[3] A recording of a superb lyrebird mimicking sounds of an electronic shooting game, workmen and chainsaws was added to the National Film and Sound Archive's Sounds of Australia registry in 2013.[10]

One researcher, Sydney Curtis, has recorded flute-like lyrebird calls in the vicinity of the New England National Park. Similarly, in 1969, a park ranger, Neville Fenton, recorded a lyrebird song which resembled flute sounds in the New England National Park, near Dorrigo in northern coastal New South Wales. After much detective work by Fenton, it was discovered that in the 1930s, a flute player living on a farm adjoining the park used to play tunes near his pet lyrebird. The lyrebird adopted the tunes into his repertoire, and retained them after release into the park. Neville Fenton forwarded a tape of his recording to Norman Robinson. Because a lyrebird is able to carry two tunes at the same time, Robinson filtered out one of the tunes and put it on the phonograph for the purposes of analysis. The song represents a modified version of two popular tunes in the 1930s: "The Keel Row" and "Mosquito's Dance". Musicologist David Rothenberg has endorsed this information.[11][12]

Status and conservation

Lyrebirds are not endangered in the short to medium term. Albert's lyrebird has a very restricted habitat and had been listed as vulnerable by the IUCN, but due to careful management of the species and its habitat the species was re-assessed to near threatened in 2009.[13] The superb lyrebird, once seriously threatened by habitat destruction, is now classified as common. Even so, lyrebirds are vulnerable to cats and foxes, and it remains to be seen if habitat protection schemes will stand up to increased human population pressure.[3]

Lyrebird emblems and logos

The lyrebird has been featured as a symbol and emblem many times, especially in New South Wales and Victoria (where the superb lyrebird has its natural habitat), and in Queensland (where Albert's lyrebird has its natural habitat).

- A male superb lyrebird is featured on the reverse of the Australian 10-cent coin.[14]

- A superb lyrebird featured on the Australian one shilling postage stamp first issued in 1932.

- A stylised superb lyrebird appears in the transparent window of the Australian 100 dollar note.

- A silhouette of a male superb lyrebird is the logo of the Australian Film Commission.

- An illustration of a male superb lyrebird, in courtship display, is the emblem of the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service.

- The pattern on the curtains of the Victorian State Theatre is the image of a male superb lyrebird, in courtship display, as viewed from the front.

- A stylised illustration of a male Albert's lyrebird was the logo of the Queensland Conservatorium of Music, before the Conservatorium became part of Griffith University. In the logo, the top part of the lyrebird's tail became a music stave.

- Australian band You Am I's 2008 album Dilettantes and its first single, Erasmus, feature a drawing of a lyrebird by artist Ken Taylor.

- A stylised illustration of part of a male superb lyrebird's tail is the logo for the Lyrebird Arts Council of Victoria.

- The lyrebird is also featured atop the crest of Panhellenic Sorority Alpha Chi Omega, whose symbol is the lyre.

- There are many other companies with the name of Lyrebird, and these also have lyrebird logos.

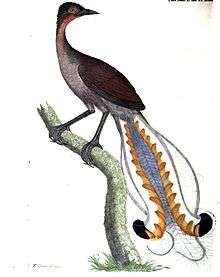

Painting by John Gould

The lyrebird is so called because the male bird has a spectacular tail, consisting of 16 highly modified feathers (two long slender lyrates at the centre of the plume, two broader medians on the outside edges and twelve filamentaries arrayed between them), which was originally thought to resemble a lyre. This happened when a superb lyrebird specimen (which had been taken from Australia to England during the early 19th century) was prepared for display at the British Museum by a taxidermist who had never seen a live lyrebird. The taxidermist mistakenly thought that the tail would resemble a lyre, and that the tail would be held in a similar way to that of a peacock during courtship display, and so he arranged the feathers in this way. Later, John Gould (who had also never seen a live lyrebird), painted the lyrebird from the British Museum specimen.

Although very beautiful, the male lyrebird's tail is not held as in John Gould's painting. Instead, the male lyrebird's tail is fanned over the lyrebird during courtship display, with the tail completely covering his head and back—as can be seen in the image in the 'breeding' section of this page, and also the image of the 10-cent coin, where the superb lyrebird's tail (in courtship display) is portrayed accurately.

References

- ↑ Davies, Thomas (4 November 1800). "Description of Menura superba, a Bird of New South Wales". Transactions of the Linnean Society. 6. London (published 1802). pp. 207–10.

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lyre-Bird". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lyre-Bird". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Lill, Alan (2004), "Family Menuridae (Lyrebirds)", in del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Christie, David, Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 9, Cotingas to Pipits and Wagtails, Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, pp. 484–495, ISBN 84-87334-69-5

- ↑ Christidis, L.; Norman, J.A. (1996). "Molecular Perspectives on the Phylogenetic Affinities of Lyrebirds (Menuridae) and Treecreepers (Climacteridae)". Australian Journal of Zoology. CSIRO Publishing. 44 (3): 215–222. doi:10.1071/zo9960215. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ↑ Boles, Walter (2011). "Lyrebird: Overview". Pulse of the Planet. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ↑ Boles, Walter E. (1995). "A preliminary analysis of the Passeriformes from Riversleigh, Northwestern Queensland, Australia, with the description of a new species of Lyrebird" (PDF). Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg. 181: 163–170.

- ↑ Reed, A.W. (1998). Aboriginal Words of Australia. Chatswood, NSW: New Holland. pp. 17; 34. ISBN 978-1-876334-16-1. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ↑ Parish, Steve; Slater, Pat (1997). Amazing Facts about Australian Birds. Oxley, QLD: Steve Parish Publishing. ISBN 1-875932-34-8.

- ↑ Tapper, James (7 May 2006). "The nation's favourite Attenborough moment". Daily Mail. Daily Mail Online. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ↑ National Film and Sound Archive: Sounds of Australia.

- ↑ Sheridan, Molly (2005). "In conversation with David Rothenberg". NewMusicBox.org. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ↑ Reilly, P.N. (1988). The Lyrebird: A Natural History. Kensington, NSW: New South Wales University Press. ISBN 0-86840-083-1.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2009). "Menura alberti". IUCN Red List. IUCN. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ↑ "Ten cents". Royal Australian Mint. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Menuridae. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Lyre-bird. |

- Lyrebirds - at the New South Wales Department of Environment and Heritage website

- The Albert's lyrebird project at the Queensland Department of Environment and Resource Management website

- Lyrebird videos at the Internet Bird Collection