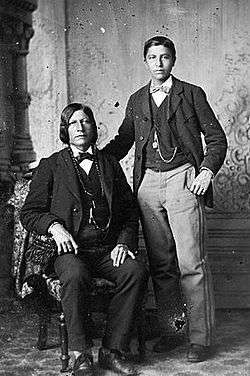

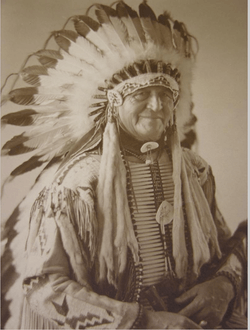

Luther Standing Bear

| Luther Standing Bear | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | Óta Kté or Plenty Kill |

| Born | December 1868 |

| Died | February 20, 1939 (age 70) |

| Nationality | Oglala Lakota |

| Other names | Matȟó Nážiŋ or Standing Bear |

| Education | Carlisle Indian Industrial School |

| Occupation | Author, educator, philosopher, and actor |

| Parent(s) | George Standing Bear (father), Pretty Face (mother) |

| Relatives | Henry Standing Bear (brother) |

Luther Standing Bear (December 1868 – February 20, 1939) (Óta Kté or "Plenty Kill" also known as Matȟó Nážiŋ or "Standing Bear") was an Oglala Lakota chief notable in American history as an Native American author, educator, philosopher, and actor of the twentieth century. Standing Bear fought to preserve Lakota heritage and sovereignty and was at the forefront of a Progressive movement to change government policy toward Native Americans.

Standing Bear was one of a small group of Lakota leaders of his generation, such as Gertrude Bonnin, and Charles Eastman, who were born and raised in the oral traditions of their culture, educated in white culture, and wrote significant historical accounts of their people and history in English. Luther’s experiences in early life, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Wild Westing with Buffalo Bill, and life on government reservations present a unique view of a Native American during the Progressive Era in American history. Standing Bear’s commentaries on Native American culture and wisdom educated the American public, deepened public awareness, and created popular support to change government policies toward Native American peoples. Luther Standing Bear helped create the popular twentieth-century image that Native American culture is holistic and respectful of nature; his classic commentaries appear in college-level reading lists in anthropology, literature, history, and philosophy, and constitute a legacy and treasury of Native American wisdom.[1]

Early life

Luther Standing Bear was born in December, 1868, on the Spotted Tail Agency, Rosebud, South Dakota, the first son of George Standing Bear and Pretty Face. Luther’s father, George Standing Bear was a Brulé Lakota chief who raised him as a traditional hunter and warrior. In the late 1870‘s, George Standing Bear built a general store, the first Native American-run business on the Spotted Tail agency.[2] In 1879, at about age eleven, his father enrolled young Luther in the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Luther’s father was aware of white peoples’ great numbers and influence, and believed that education was the path the Indians must follow in order to survive in the 'white world'. Luther was taught to be brave and unafraid to die, and was determined to do heroic deeds to bring honor to his family. Standing Bear’s father celebrated his son’s heroism by inviting his friends to a gathering, where he gave away seven horses and all the goods in his dry goods store.[3]

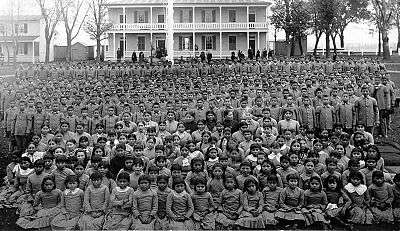

Carlisle Industrial School for Indians

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, was one of the earliest Native American boarding schools, whose goal was cultural assimilation of Native Americans.[4] Luther was one of the first students to arrive when Carlisle opened its doors in 1879.[5] Once there, he was asked to choose a name from a list on the wall. He randomly pointed at the symbols on a wall and named himself Luther, and his father's name became his surname. Luther soon became Captain Richard Henry Pratt’s model Carlisle student. Like many other Carlisle students, Luther had high personal regard for Captain Pratt.[6] Standing Bear interpreted and recruited students for Pratt at Pine Ridge, South Dakota, led the Carlisle Indian Band across the Brooklyn Bridge upon its opening ceremony on May 24, 1883, and served as a student intern for John Wanamaker in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Carlisle gave its students opportunities to interact and live in the white world. During the summer months students were enrolled in an “outing program” which found them in jobs with white families for which they earned their first wages.[7]

Red flannel underwear

"The civilizing process began at Carlisle began with clothes. Whites believed the Indian children could not be civilized while wearing moccasins and blankets. Their hair was cut because in some mysterious way long hair stood in the path of our development. They were issued the clothes of white men. High collar stiff-bosomed shirts and suspenders fully three inches in width were uncomfortable. White leather boots caused actual suffering. Standing Bear later wrote that red flannel underwear caused ‘actual torture.' He remembered the red flannel underwear as the worst thing about life at Carlisle.” [8]

Eclipse

“One day an astronomer came to the school and gave a talk and explained that there would be an eclipse of the moon the following Wednesday night at twelve o’clock. We did not believe it. When the moon eclipsed, we readily believed our teacher about geography and astronomy.” [9]

Bows and arrows

"In 1881, after the school closed for the summer vacation, some of the boys and girls were placed out in farmers’ homes to work throughout the summer. Those who remained at school were sent to the mountains for a vacation trip. I was among the number. When we reached our camping place, we pitched out tents like soldiers all in a row. Captain Pratt brought along a lot of feathers and some sinew, and we made bows and arrows. Many white people came to visit the Indian camp, and seeing us shooting with the bow and arrow, they would put nickels and dimes in a slot of wood and set them up for us to shoot at. If we knocked the money from the stick, it was ours. We enjoyed this sport very much, as it brought a real home thrill to us.” [10]

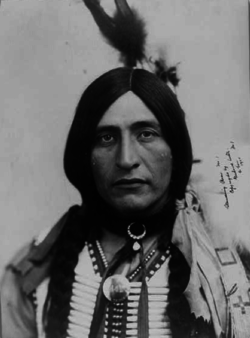

Sitting Bull

_edit.jpg)

“One evening while I was going home from work, I bought a paper, and read that Sitting Bull, the great Sioux medicine man, was to appear at one of the Philadelphia theaters. The paper stated that he was the Indian who killed General Custer! The chief and his people had been held prisoners of war, and now here they were to appear in a Philadelphia theater. So I determined to go and see what he had to say, and what he was really in the East for. I had to pay fifty cents for a ticket. The theater was decorated with many Indian trappings such as were used by the Sioux tribe of which I was a member.

"On the stage sat four Indian men, one of whom was Sitting Bull. There were two women and two children with them. A white man came on stage and introduced Sitting Bull as the man who had killed General Custer (which, of course, was absolutely false). Sitting Bull arose and addressed the audience in the Sioux tongue, as he did not speak nor understand English. He said, ‘My friends, white people, we Indians are on our way to Washington to see the Grandfather, or President of the United States. I see so many white people and what they are doing, that it makes me glad to know that some day my children will be educated also. There is no use fighting any longer. The buffalo are all gone, as well as the rest of the game. Now I am going to shake the hand of the Great Father at Washington, and I am going to tell him all these things.’ Then Sitting Bull sat down. He never even mentioned General Custer’s name.

"Then the white man who had introduced Sitting Bull arose again and said he would interpret what the chief had said. He then started telling the audience all about the Battle of the Little Big Horn, generally spoken as the ‘Custer massacre.’ He mentioned how the Sioux were all prepared for battle, and how they had swooped down on Custer and wiped his soldiers all out. He told so many lies that I had to smile. Then the white man said that all those who wished to shake hands with Sitting Bull would please line up if they cared to meet the man who had killed Custer. It made me wonder what sort of people the whites were, anyway. Perhaps they were glad to have Custer killed, and were really pleased to shake the hand with the man who had killed him!" [11]

School recruiter

Luther was a school recruiter for Captain Richard Henry Pratt and periodically visited reservations. He was sincere in his desire to show what we had learned, and persuaded parents to send their children to Carlisle by his appearance, language and skills. However, many children died in boarding schools and parents were fearful to let them go. Moreover, many parents were treated unfairly and had not been notified until after the children died and were buried. It was not the negligence of Captain Pratt, but rather lax Indian agents who would set aside letters from Carlisle until the parents came into the agency for something. While many parents were proud of Luther, they were afraid to send their children away fearing they would never see them again.[12] Luther got mixed reception home on the reservation. Some were proud of his achievements while others lamented that he had, in effect, become a white man.[13] He was happy to be home and some of his relatives aid that he “looked like a white boy dressed in eastern clothes.” Luther felt proud to be compared to a white boy. But others would not shake his hand because some returning Carlisle students were ashamed of their culture, and a few even tried to pretend that they did not speak Lakota. The difficulties of returning Carlisle students disturbed white educators. Returning Carlisle students found themselves stranded between two cultures, and not accepted by either. Some rejected their educational experiences and “returned to the blanket”, casting off white ways. Others found it more convenient and satisfying to remain in white society. Most were able to adjust at least partially to both worlds.[14]

Bugler

Luther Standing Bear was a musician and played the classic coronet and military bugle calls. “After I had learned to play a little, I was chosen to give all the bugle calls. I had to get up in the morning before the others and arouse everybody by blowing the morning call. Evenings at ten minutes before nine o’clock I blew again. Then all of the boys would run for their rooms. At nine o’clock the second call was given, when all lights were tuned out and we were supposed to be in bed. Later on I learned the mess call, and eventually could blow all the calls of the regular army.”[15] The Carlisle Indian band of brass instruments performed at football games, world expositions and presidential inaugural parades. On May 24, 1883, Luther led the first “real American” band to cross the Brooklyn Bridge at its grand opening ceremony.

George Standing Bear's visit

English was the only language permitted at Carlisle, which presented a problem for Luther when his father visited in 1880. He had to write a note to Captain Pratt for permission to speak to his father in Lakota. Pratt took such a liking to Luther's father that he took him to visit Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington. When the elder Standing Bear returned to Carlisle, visibly impressed with the power of whites, he told his son that he must study hard and learn the white man’s ways.[16]

“Just before returning to the West, father was invited into our Chapel to listen to the service. He asked me what it was, and I told him it was the white man’s religion which was discussed in that room. He came in and sat with us boys. During the preaching he sat very reverently and listened attentively to all that was said, although he could not understand a single word. His attention to the service pleased Captain Pratt exceedingly. When my father was ready to depart, he was presented with a well-made top-buggy and a set of harness, all of which were made at the school. I was delighted at seeing my father so well treated and recognized. Other chiefs had visited us, but my father was the first Indian to receive such courteous recognition and agreeable presents.[17]

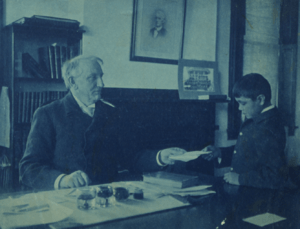

Intern for John Wanamaker

In 1883, Luther was sent to work as an intern for John Wanamaker in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Captain Pratt told Luther: “My boy, you are going away from us to work for this school. Go and do your best. The majority of white people think the Indian is a lazy good-for-nothing. They think he can neither work nor learn anything; that he is very dirty. Now you are going to prove that the red man can learn and work as well as the white man. If John Wanamaker gives you the job of blacking his shoes, see that you make them shine. Then he will give you a better job. If you are put into the office to clean, don’t forget to sweep up under the chairs and in the corners. If you do this well, he will give you better work to do.” [18]

For a while, Luther and another Carlisle student boarded with white boys in Philadelphia. “A big wagon left the school every morning carrying several of the boys who worked out. We were invited to ride with them. After the first few mornings, however, I preferred to ride in the street carts, rather than listen to the rough, profane language which these boys used on their way to work. And these boys were supposed to be civilized, having had good teachers and good education, yet they used the vilest of language, to which I did not care to listen.” [19]

“About this time the whole Carlisle School made a visit to Philadelphia. A meeting was held in a large hall, and Captain Pratt spoke of the work of the school, and how all the Indian boys and girls were doing. Then John Wanamaker had me come up on the stage. He told the audience that I was working for him and that I was a Carlisle boy. He stated that I had been promoted from one department to another, every month getting better work and better money, and in spite of the fact that he employed as many as one thousand people in his establishment, he never promoted anyone as rapidly as he had me. That brought considerable applause, and Captain Pratt was very proud of me.[20]

Back on the reservation

In 1884, following his final term at Carlisle, Standing Bear, armed with a recommendation by Captain Pratt, returned home to the Rosebud Agency, Rosebud, South Dakota, where he was hired as an assistant at the reservation's school at the salary of three hundred dollars a year.[21] In 1890, some time after Wounded Knee, Luther moved from Rosebud and followed his father and brother Ellis Standing Bear to Pine Ridge, South Dakota. Pine Ridge provided a series of varying employment and family ventures. In 1891, Luther became principal of a reservation day school. Standing Bear also worked in his uncle’s little general store. One day they were talking about the delay in mail delivery. “I told my uncle that John Wanamaker, the man for whom I had worked in Philadelphia, was Postmaster-General, and that I would write and see if we could not have a post office established at his camp. I suggested that we call it Kyle. It was a short name and easy to spell. When Mr. Wanamaker received my letter, he replied immediately. He was pleased with my suggestion, but said that he could not appoint me postmaster, as I was an Indian. It would have to be some white man. There was a Joseph Taylor who was one of our missionaries, and we sent his name. He received the appointment, but I took care of the office.” [22] Later, Luther opened a dry goods store with his brother Ellis at Pass Creek and started a small ranch raising horses and cattle. Standing Bear organized public meetings at his dry goods store in Pine Ridge to discuss treaties and current events.[23]

Marriage and children

Luther married Nellie DeCrory in 1886, and they had six children: Lily Standing Bear, 1886; Arthur Standing Bear, 1888; Paul Francis Standing Bear, 1890; Emily Standing Bear, 1892; Julia Standing Bear, 1894; and Alexandra Birmingham Cody Standing Bear. June 7, 1903. Around 1899, Standing Bear married Laura Cloud Shield and the couple had one additional child, Eugene George Standing Bear, c. 1900.[24]

Carlisle Wild Westers

Many Oglala Lakota Wild Westers from Pine Ridge, South Dakota attended Carlisle.[25] Carlisle Wild Westers were attracted by the adventure, pay and opportunity and were hired as performers, chaperons, interpreters and recruiters. Wild Westers from Pine Ridge enrolled their children at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School from its beginning in 1879 until its closure in 1918. In 1879, Oglala Lakota leaders Chief Blue Horse, Chief American Horse and Chief Red Shirt enrolled their children in the first class at Carlisle. They wanted their children to learn English, trade skills and white customs. Ann Rinaldi, author of 'My Heart is on the Ground: the Diary of Nannie Little Rose, a Sioux Girl', later wrote "Those first Sioux children who came to Carlisle could not have been happy there. But it was their only chance for a future." [26]

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in England

In 1902, with his wife Nellie and their children, Standing Bear joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and traveled through England for eleven months. Luther was hired as an interpreter and chaperone for seventy-five Indians, and also performed as a skilled horseback rider and dancer. [27] The most difficult part of Luther's job was keeping the Indians sober.[28]

Whiskey and half-pay

Luther recalled his first speech on sobriety. “My relations, you all know that I am to take care of you while going across the big water to another country, and all the time we are to stay there. I have heard that when anyone joins this show, about the first thing he thinks of is getting drunk. I understand that regulations of the Buffalo Bill show require that no Indian shall be given any liquor. You all know that I do not drink, and I am going to keep you all from it. Don’t think because you may be closely related to me I will shield you, for I will not. I will report to Colonel Cody immediately anyone I find drinking.” [29]

“Many of the Indians would want to go out and buy trinkets and things to carry back home, such as nice blankets and shawls. But during the rainy weather some of them thought they had an excuse to drink. They said they thought it kept them warm. I saw at once that this must not go on, as a little whiskey always calls for more. So I called all the Indians together in council, and explained to them that I had noticed they were beginning to look for liquor again and that it was not good for them. Then I said: “I am going to make a new rule with you. Every man and woman hereafter will receive only half their pay. The balance will be kept in my care until near the end of the season. Then those of you who think you must be spending your money all the time will have something to take home with you when your work is done.’ Some, of course, did not like this plan. While they knew it was for their best interest, still they did not want to do without their liquor. But the majority fell right in with my proposition. They knew I would be honest with them, and that their money was safe with me. So it was agreed that on each pay day half of the money should be put away until the show closed. Further, each man was warned that he must be more careful about drinking.” [30]

The King of England

“One day Colonel Cody sent for me to come to his private office. Wondering what he would want of me, I knocked at his door. He invited me in, remarking, ‘Sit down, Standing Bear. I have sent for you because I want you to tell you something of importance. The Big Chief of this country, the King of England, has promised to attend a performance of our show. Now I want you to go back to your people, call them all together, and tell them all about it. Tell them to be very careful about their clothes; to see that they are perfectly clean and neat for that particular performance. If anything needs repairs, tell them to attend to it at once. We must please the King at this performance. Rehearse your Indians well so they will do their best for me. If the King likes our show, it will please the people of this country. I have observed your own costume. It is very fine, and when the King attends the show, I want you to do an Indian dance in front of his box. Will you do this for me?” “Everything worked splendidly. When it came time for the Indians to come in with their village in the center of the arena, we started the dance in which I was to appear before the King of England. I had a beautiful lance, and as the dance proceeded I worked over toward the King’s box. There I shook the lance in his face and danced my very prettiest, you may be sure. The King had been very dignified thus far, and had not even smiled. But when I got down to doing my fancy steps and gave a few Sioux yells, he had to smile in spite of himself. I saw that I had made a hit with him and was very happy. After the show, Buffalo Bill brought the King and his party around the inside of the arena. In front of him walked a big man who seemed to keep his eyes roving about all the while. I think he must have been the King’s personal bodyguard. Buffalo Bill brought the King over to me and we were introduced. We shook hands, although neither of us said a word. But I had the honor of being introduced to King Edward VII, the monarch of Great Britain.” [31]

Pancakes

“One morning as I came into the dining-tent I noticed that everybody but the Indians had been served with hot cakes. This did not bother me much, as Indians do not eat such food. At dinner-time that same day, when I sat down to our table, I saw to my surprise that there were pancakes before us. These were the ‘left-overs’ from the morning, and now the cook wanted to feed them to us. Although I was very angry, I made no remark, but quietly left the table and went over where Buffalo Bill and the head officials of the show were eating dinner. Colonel Cody asked, ‘What is it, Standing Bear?’ ‘Colonel Cody,’ I replied, ‘this morning all the other races represented in the show were served with pancakes, but the Indians were not given any. We do not object to that, as we do not care for them; but now the cook has put his old pancakes on our table and expects us to eat what was left over from breakfast, and it isn’t right.’ Buffalo Bill’s eyes snapped, as he arose from the table. ‘Come with me, Standing Bear,’ he exclaimed. We went direct to the manager of the dining-room, and the Colonel said to him, ‘Look here, sir, you are trying to feed my Indians left-over pancakes from the morning meal. I want you to understand, sir, that I will not stand for such treatment. My Indians are the principal feature of this show, and they are the one people I will not allow to be misused or neglected. Hereafter, see to it that they get just exactly what they want at meal-time. Do you understand me, sir”’ ‘Yes, sir, oh, yes, sir,’ exclaimed the embarrassed manager. After that, we had no more trouble about our meals.” [32]

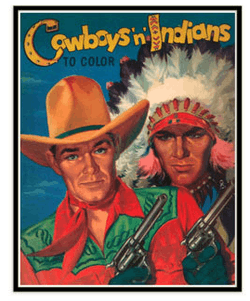

Cowboys 'n' Indians

“There were a great many cowboys with the show. There was a chief of the cowboys who had general supervision over both horses and men. When an unbroken horse would be brought in, this cowboy chief would give it to an Indian to ride bareback. After the animal was well broken, it would be taken away from the Indian and given to a cowboy to ride. Then the Indian would be given another unbroken horse. For a while we said nothing about it, but finally it began to be just a little too much to stand. One day one of the Indians came to me just before it was time to enter the arena. His horse was saddled and bridled, but he was leading the horse by the bridle. I asked him what was the matter, and he said it was a wild horse and he was not going to ride it into the arena. I went to the chief cowboy and said, ‘I do not think you are doing right. You know our Indian boys have to ride bareback, but you always give them the wild horses to ride. Then, when they have the horse nicely broken, you give to a cowboy. Why don’t you give the wild horses to the cowboys to break in? They ride on saddles, and it would not be so hard for them.’ But the chief cowboy only said, “Well, I can’t be bothered by a little thing like that. You will have to see Buffalo Bill about the horses.’ But I retorted, “You know very well that Buffalo Bill does not know what you do with the horses. He does not know that you give the wild ones to the Indian boys to ride until they are broken in. Give that horse back to that Indian boy or he will not go into the arena today.’ That was all, but the boy got his horse in time to enter the arena with the others. Just as I was ready to go back to the Indians, I looked at Buffalo Bill, and he had a twinkle in his eye. After that, we had no more trouble with the horses. Although Buffalo Bill never said anything to me, I knew he had fixed things to our satisfaction.” [33]

Baby in Birmingham

“While we were showing in Birmingham, England, a little daughter was born to us. The morning papers discussed the event in big headlines that the first full-blooded Indian baby had been born at the Buffalo Bill grounds. Colonel Cody was to be its godfather, and the baby was named after the reigning Queen of England. The child’s full name was to be Alexandra Birmingham Cody Standing Bear. The next morning Cody came to me and asked if my wife and baby could be placed in the side-show. He said the English people would like to see the face of a newly born Indian baby lying in an Indian cradle or ‘hoksicalaa postan.' I gave my consent, and the afternoon papers stated that the baby and mother could be seen the following afternoon. Long before it was time for the show to begin, people were lining up on the road. My wife sat on the raised platform, with the little one in the cradle before her. The people filed past, many of them dropping money in a box for her. It was a great drawing card for the show; the work was very light for my wife, and as for the baby, before she was twenty-four hours old she was making more money than my wife and I together." [34]

Train wreck

In 1903, Luther signed up for another tour with Buffalo Bill. However, the touring season was cut short on April 7, 1903, by a terrible accident in Maywood, Illinois, when the rear cars of Luther's train were struck by another train. Three young Indians were killed and twenty-seven performers badly injured. Luther was seriously injured and almost died. He suffered a dislocation of both hips, a left broken leg below the knee, a left broken arm, two broken ribs, a broken collar bone, a broken nose and deep gashes on head. As a result, Luther and his family could not return to Buffalo Bill's Wild West.[35]

Chief of the Oglala Lakota

After returning to Pine Ridge in 1905, Standing Bear was chosen as a chief of the Oglala Lakota on July 4, 1905.[36] There was a great celebration. “In different places they started to sing songs of praise for me. Frank Goings, the chief of the Indian Police and interpreter for the agency, had brought the Boys’ Band from the boarding school, with all their instruments. In between the Indian songs, the band would play. I then started giving away things I had brought along. I kept this up until I had given away everything I owned, and my wife and I walked away with practically nothing. We figured that we gave away that day about a thousand dollars’ worth of goods ourselves, not counting all the presents that had been donated to be distributed.”

“A chief receives no salary, and at gatherings it is up to him to see that everything is done properly. We have no more war councils, but if a Commissioner is sent from Washington to make any sort of contract with the tribe, it is up to the chief to be present and investigate the matter. That is the law among the Indians. It is a great honor to receive the title of ‘Chief,’ but there is much hard work about it also.”[37]

Leaving the reservation

In 1905, Standing Bear decided to leave. He was no longer willing to endure existence under the control of an overseer.[38] Luther sold his land allotment and bought a house in Sioux City, Iowa, where he worked as a clerk in a wholesale firm.[39] After a brief job doing rodeo performances with Miller Brothers 101 Ranch in Oklahoma, he moved to California to seek full-time employment in the motion picture industry.[40] In later years, Luther reflected upon his decision to leave the reservation: “Sixteen years ago I left reservation life and my native people, the Oglala Sioux, because I was no longer willing to endure existence under the control of an overseer. For about the same number of years I had tried to live a peaceful and happy life; tried to adapt myself and make re-adjustments to fit the white man’s mode of existence. But I was unsuccessful. I developed into a chronic disturber. I was a bad Indian, and the agent and I never got along. I remained a hostile, even a savage, if you please. And I still am. I am incurable.” [41] While Standing Bear left the confinement of the reservation, he continued his serious responsibilities and as an Oglala Lakota chief, fighting to preserve Lakota heritage and sovereignty through public education.

Hollywood and the movies

In 1912, Standing Bear moved to California and was recruited as a consultant by motion picture director Thomas H. Ince because of his experience as a performer with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Standing Bear made his screen debut in “Ramona” in 1916. From 1912 to the 1930s, Standing Bear was employed in the motion picture industry and appeared in many early Westerns and worked alongside Tom Mix, Douglas Fairbanks and William S. Hart. Luther Standing Bear appeared in a dozen films, playing both Indian and non-Indian roles including Ramona, 1916; Bolshevism on Trial, 1919; White Oak, 1921; The Santa Fe Trail, 1930; The Conquering Horde, 1931; Texas Pioneers, 1932; Murder in a Private Car, 1934; Cyclone of the Saddle, 1935; The Miracle Writer, 1935; Fighting Pioneers, 1935; Circle of Death, 1935; and Union Pacific, 1939.[42]

Indian actors’ guilds

Standing Bear was a member of the Screen Actors Guild of Hollywood.[43] Standing Bear was critical of Hollywood’s portrayals of Native Americans, and wanted only Native Americans to play Native Americans and appear on the screen in leading and meaningful roles. In 1926, along with other Indian actors in Hollywood created the "War Paint Club."[44] Ten years later, Luther joined Jim Thorpe in creating the Indian Actors Association to protect rights and characters of Native American actors from defamation or ridicule.[45]

Luther Standing Bear's commentaries

The Carlisle Indian School and Wild Westing

Wild Westing and the Carlisle Indian Industrial School were portals to education, opportunity and hope, and came at a time when the Lakota people were depressed, impoverished, harassed and confined. Luther’s commentaries on his early life, attending the Carlisle Indian School, Wild Westing with Buffalo Bill and reservation life are unique stories of a Native American during the Progressive Era in American history.

Protecting Native American heritage and sovereignty

Between 1928 and 1936, Standing Bear wrote four books and a series of articles about protecting Lakota culture and in opposition to government regulation of Native Americans. Luther‘s commentaries challenged government policies regarding education, assimilation, freedom of religion, tribal sovereignty, return of lands and efforts to convert the Lakota into sedentary farmers. Standing Bear believed that white people had much to teach Indians and that Indian people had much to teach whites. He argued that the Bureau of Indian Affairs should employ Indians in positions of authority, adopt a policy of bilingual education, employ Indians to teach Indians and teach Native American history and culture in all public schools. Standing Bear argued for a change of policy in the education of Native American children:

“The Indian children should have been taught how to translate the Sioux tongue into English properly; but the English teachers only taught them the English language, like a bunch of parrots.”

“The Indian, by the very sense of duty, should become his own historian, giving account of the race, fairer and fewer accounts of the wars and more of the statecraft, legends, languages, oratory and philosophical conceptions. No longer should the Indian be dehumanized in order to make material for lurid and cheap function to embellish street stands.”

“A fair and correct history of the native American should be incorporated into the curriculum of public schools. Indians should be taught their own history, and schools created where tribal and Indian thought would be taught on the Indian pattern by Indian institutors. All American would benefit, for “in denying the Indian his ancestral rights and heritages the white race is robbing itself.”

Standing Bear opposed the Dawes Act's policy of privatization of communal holdings of Native American tribes, and was critical of government support of missionaries who undermined Sioux religion, as did the prohibition against the Sun Dance, the most important religious and social event in the yearly cycle of Sioux life.[46]

Books, articles and forums

Between 1928 and 1934, Progressives organized and launched a national education campaign to change government policies towards Native Americans. The campaign began in 1928 with the publication of Standing Bear’s book “My People the Sioux” and the release of John Collier’s Meriam Report. During this period, Standing Bear published four books and numerous articles to educate the public about Lakota culture, and toured the forums of the American lecture circuit building critical support for an “Indian New Deal.” Luther was at the forefront of the Progressive movement and his commentaries educated the American public, deepened awareness and created popular support to change government policies toward Native American peoples. At the time, Native American authors were a rarity, and Standing Bear’s books were considered culturally significant and reviewed by the New York Times.[47]

In 1931, Standing Bear published My Indian Boyhood, a classic memoir of life, experience and education of a Lakota child in the late 1800s. That year, after an absence of twenty years, Standing Bear visited Pine Ridge, South Dakota. He was so distressed by the desperate plight of his people that he wrote “The Tragedy of the Sioux” in American Mercury condemning federal Indian policy for the continued destruction of the Lakota.[48] “Land of the Spotted Eagle”, published in 1933, is an ethnographic description of traditional Lakota life and customs, criticizing whites’ efforts to “make over” the Indian into the likeness of the white race. Here, Standing Bear observed, “White men seem to have difficulty realizing that people who live differently from themselves still might be traveling the upward and progressive road of life.” [49] In 1933, Standing Bear also published "What the Indian Means to America".[50] In 1934, Standing Bear published a collection of Lakota tales and legends in “Stories of the Sioux”.

Standing Bear and the Indian New Deal

Luther Standing Bear was at the forefront of the Progressive movement, and joined with advocate John Collier, the Indian Rights Association and others to protect Native American religion and sovereignty. Standing Bear’s commentaries on Native American culture and wisdom educated the American public, deepened public awareness and created popular support to change in government policies toward Native American peoples. In 1928, Standing Bear’s “My People the Sioux” and Collier’s Meriam Report were published, launching an organized campaign to challenge government policies limiting Native American religion and sovereignty.[51]

Between 1928 and 1934, Luther Standing Bear published four books and numerous articles to educate the public about Lakota culture, and toured the forums of the American lecture circuit building critical support for a “Indian New Deal.”

In 1933, Collier was appointed Commissioner for the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the President Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, and Standing Bear wrote to President Franklin D. Roosevelt that Congress should legislate that the history and culture of Native Americans be made part of the curriculum of public schools. [52] The next year, Collier introduced what became known as the Indian New Deal with Congress' passage of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 legislation reversing fifty years of assimilation policies by emphasizing Indian self-determination and the Dawes Act's policy of privatization of communal holdings of Native American tribes.[53] Luther’s essay “The Tragedy of the Sioux” in American Mercury and his book Land of Spotted Eagle were published near the end of the Progressive campaign and had wide impact influencing John Collier’s Indian New Deal policies and fighting to restore tribal culture and sovereignty.[54]

Death

On February 20, 1939, Luther Standing Bear died in Huntington Beach, California, at age of 70 of the flu while on the set of the film Union Pacific. Standing Bear was buried in the Hollywood Forever Cemetery, Los Angeles, California, far from his Lakota homeland, with his sacred pipe.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Standing Bear "opened the reservation world and the Lakota point of view to the non-Indian.” Alida S. Boorn, “Oskate Wicasa (One Who Performs)” (hereinafter “Oskate Wicasa”), Department of History, Central Missouri State University, (2005), p.110. John R. Shook, “The Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers, Volume 1”, (2005), p.2312. Phillip A. Greasily, “Dictionary of Midwestern Literature, Volume 1: The Authors, (2001), p.472. See http://www.firstpeople.us/FP-Html-Wisdom/ChiefLutherStandingBear.html

- ↑ Luther Standing Bear, “My People the Sioux," (1928), p.viii. Joseph Agonito, “Lakota Portraits: Lives of the Legendary Plains People” (hereinafter "Agonito") (2011), p.235. Donovin Arleigh Sprague, "Rosebud Sioux," p. 40 (2005)

- ↑ Joseph Agonito, “Lakota Portraits: Lives of the Legendary Plains People” (hereinafter “Agonito”)(2011), p.237

- ↑ Witmer, p.xvi. Carlisle had developed something of a rivalry with Harvard, and though the Indians had never beaten the Crimson, they always gave them a game. The Indians both admired and resented the Crimson, in equal amounts. They loved to sarcastically mimic the Harvard accent; even players who could barely speak English would drawl the broad Harvard a. But Harvard was also the Indians' idea of collegiate perfection, and they labeled any excellent performance, whether on the field or in the classroom, as "Harvard style." Sally Jenkins, “The Real All Americans”, (hereinafter "Jenkins")(2007), p.198.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.133.

- ↑ My People the Sioux”, p.xx.

- ↑ My People the Sioux”, p.vi.

- ↑ Luther Standing Bear, “Land of the Spotted Eagle”, (1933), p.232-233.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.155.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux," p.154-155.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.184-186.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.162-163.

- ↑ Agonito. p.241.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.xx.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.149.

- ↑ Agonito. p.239. “My People the Sioux”, p.151-152.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.152.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.178.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.182.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.182-184.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.xxii.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.234.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p. xvii.

- ↑ See Stevens, “Tiyospaye: An Oglala Genealogy Resource, http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~mikestevens/2010-p/i61.htm#8796

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.131.

- ↑ Ann Rinaldi, “My Heart is on the Ground: the Diary of Nannie Little Rose, a Sioux Girl, Carlisle Indian School, Pennsylvania, 1880,” (1999), p. 177.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.254.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.viii-x.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.249.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.262-263.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.254-257.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.260-261.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.263-265.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.266-267.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.270-272. Agonito, p.245-246.

- ↑ Luther Standing Bear (1 November 2006). My People the Sioux. U of Nebraska Press. p. 269. ISBN 0-8032-9361-5.

- ↑ While George Standing Bear was Brulé Sicangu, he and his family identified themselves with the Oglala of Pine Ridge. Donovin Arleigh Sprague, “Rosebud Sioux”,(2005), p.40.“My People the Sioux”, p.274-266.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p. xviii.

- ↑ Agonito, p.247.

- ↑ Phillip A. Greasily, “Dictionary of Midwestern Literature, Volume 1: The Authors, (2001), p.472.

- ↑ “Land of the Spotted Eagle”, p.260.

- ↑ Agonito, p.247. Oskate Wicasa, p.112.

- ↑ Agonito, p. 248-249.

- ↑ See "Indian Actors Bury the Hatchet in Hollywood 'War Paint Club'", Christian Science Monitor, November 24, 1926, p.5A.

- ↑ See, Angela Aleiss, "Making The White Man's Indian: Native Americans And Hollywood Movies", (2005), p.54.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p.x-xxvii., p.277. “Land of the Spotted Eagle”, p. 254-255.

- ↑ “My People the Sioux”, p. xxi.

- ↑ The American Mercury, (1931), p.273.

- ↑ Agonito p.250-251.

- ↑ James E. Seelye, Jr. and Steven A. Littleton, Editors, "Voices of the American Indian Experience", (2013), p.508.

- ↑ The Meriam Report revealed the failures of federal Indian policies and how they had contributed to severe problems with Indian education, health and poverty. Prior to this time, criticism of the Bureau of Indian Affairs had been directed at corrupt and incompetent officials rather than the policies. This campaign fought against legislation and policies that were detrimental to Native Americans.

- ↑ Agonito, p. 252.

- ↑ Collier emerged as a federal Indian policy reformer in 1922 and strongly criticized the Bureau of Indian Affairs policies and implementation of the Dawes Act. His work led Congress to commission a study in 1926-1927 of the overall condition of Indians in the United States. The results were called the Meriam Report. Collier served as Commissioner for the Bureau of Indian Affairs from 1933-1945.

- ↑ Agonito, p. 253. Land of the Spotted Eagle, p.xi.

External links

Media related to Luther Standing Bear at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Luther Standing Bear at Wikimedia Commons- Luther Standing Bear at the Literary Encyclopedia.

- Luther Standing Bear at the Native American Authors Project.

- Chief Standing Bear at the Internet Movie Database at IMDB.com

- Luther Standing Bear at Find a Grave