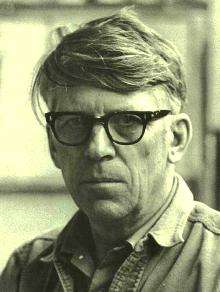

Luke Lindoe

| Luke Orton Lindoe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

8 March 1913 Bashaw, Alberta, Canada |

| Died | 4 December 2000 (aged 87) |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Occupation | Clay worker |

| Known for | Plainsman Clays |

Luke Orton Lindoe (8 March 1913 – 4 December 2000) was a Canadian painter, sculptor, potter, businessman and ceramic artist who did most of his work in Alberta, Canada. For long periods he was based in Medicine Hat.

Lindoe gained a deep understanding of the properties of clay, with which he experimented all his life. Although trained in art colleges in Alberta and Ontario, he received no formal qualification. He worked in many different jobs, including mineral prospecting, coal mining, teaching art, producing potting clay and manufacturing ceramic products such as ashtrays. He also filled many commissions for stone or concrete murals on public buildings. During his life he gained a high reputation as a mentor of ceramics artists and for his own oil paintings, sculptures and ceramics.

Early years

Luke Orton Lindoe was born on 8 March 1913 in Bashaw, Alberta.[1] For the first sixteen years of his life Lindoe and his mother wandered in western Canada and the United States. He attended twenty-eight schools, but never completed grade ten.[2] In 1933 Lindoe tried to start a farm to the south of Fort St. James in British Columbia. He put up buildings and bought a few animals. After a hopeless struggle that winter, he was forced to abandon the project and sell out.[3]

Lindoe decided that he wanted to study art. He went for help to his father, who was general manager of two mines in Coleman, Alberta. He worked as an underground coal miner while studying painting and then sculpture at the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art, now the Alberta College of Art and Design (1935–40) in Calgary. After four years he had not completed enough hours to qualify for a diploma. He went to Toronto to study sculpture at the Ontario College of Art (OCA) while his funds lasted (1940–41), and there became interested in ceramics.[2][1] In 1939 he became an Associate Member of the Alberta Society of Artists. Lindoe married Vivian Lamont in 1940, a fellow student at the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art. Their son Allan was born in 1944, and Carroll was born in 1946.[1]

Lindoe moved to Medicine Hat, Alberta in 1941, where he worked for Medicine Hat Potteries. He then became a production foreman at Redcliff Potteries. In 1942 he gained a job as an assistant draftsman in Calgary with a subsidiary of Consolidated Mining and Smelting.[1] In 1942 Lindoe found a job as a geological surveyor for Imperial Oil, and spent three years mapping the Whitemud Formation in Cypress Hills. At the end of this period he was an expert in the local clays. During the winters he was absorbed in painting.[4] Lindoe developed a life-long interest in researching the properties of clay.[5] Virginia Christopher knew Lindoe for many years. She said of his ability to find the best deposits of clay, “He had an intuition about water courses ... He understood the drift of things in the Cypress Hills, he knew where the deposits would end up.”[6]

Painter and teacher

In 1945 Lindoe threw up his job and moved to Salmon Arm, British Columbia to paint full time.[4] He returned to Calgary and was an instructor at the Alberta College of Art from 1947 to 1957, where he developed the ceramics department.[5] One of his students was Henry Bonli, who became a painter and interior designer.[7] Lindoe also pushed Walter Dexter into becoming a ceramic artist, and was Dexter's mentor for many years.[8]

In 1952 Lindoe resigned from all exhibiting societies. He said, "I had hit the wall and had neither the wisdom nor the courage to carry on in an environment that I knew was alien to me, but it wasn’t until 1964 or ’65 that I started to get the courage to expose myself artistically again."[6] He and J. Sproule formed a partnership that year to develop a small pottery studio, first called Lindoe Studios and later Ceramic Arts. Lindoe had the expertise and Sproule provided the money. The studio opened in 1954, with a 40 cubic feet (1.1 m3) updraft kiln that Lindoe had built by hand. It mainly produced cast pottery items, such as square ashtrays. The partnership was not successful and broke up after two years.[9] Lindoe left College of Art after a disagreement over its direction in 1957.[5]

Businessman

Lindoe returned to Medicine Hat in 1957 to enter the brick and tile industry.[9] He joined the I-XL company of the Sissons brothers, which had gradually been expanding by taking over other companies. Lindoe was hired as director of research and mining, an area where I-XL was struggling, and turned the operation around. As a condition of employment Lindoe had a studio and then a gas kiln at the plant, where he developed his skills as a potter.[10] Lindoe had been hired on the basis that he understood ceramics, but in fact he was a potter and his expertise was locating clay and its properties.[11]

In 1961 Lindoe and his first wife dissolved their marriage. In 1962 he married Gail Buckholz, a student at the Alberta College of Art. Their son Sebit was born in 1964, and Simon in 1968.[1] In 1964 Lindoe left his job at I-XL Industries and used $5,000 cash and $5,000 of credit to launch Plainsman Clays, a company that would supply potter's clay to institutions.[11] The company began as a one-person operation, although Lindoe got some help when needed from his son and daughter. The business grew fast, and in 1971 expanded into new premises.[11] Lindoe sold Plainsman Clay in 1981.[1]

In 1979 the Luke Lindoe Library at the Alberta College of Art was named in Luke Lindoe's honor. In 1983 he relocated to Peachland, British Columbia. Later he moved back to Medicine Hat.[1] Luke Orton Lindoe died in Medicine Hat on 4 December 2000 at the age of 87.[12]

Work

Lindoe had a spare style in his paintings and ceramics. His later paintings became increasingly simplified and abstract, reduced to basic forms with subtly shading colors. His ceramics were also decorated with richly layered abstract patterns.[6] Lindoe was one of the first ceramic artists in Canada to be commissioned to make murals. St. Mary’s Cathedral in Calgary includes Lindoe's concrete reliefs. The outside wall of the Royal Alberta Museum in Edmonton has a limestone relief.[5] Luke Lindoe stated in March 1992,[3]

It seems to me that my art says all that needs to be said about my art. I think of it as being simple, direct response to my life, everything is familiar and recognizable. There are no obscure philosophical or psychological implications; I observe and I interpret. That's all there is to it.[3]

Exhibitions

Lindoe's ceramic work has been widely exhibited in North America, Europe and Japan.[5] Lindoe's work was shown in many group exhibitions. Sole exhibitions included:[1]

- 1953 Luke Lindoe Ceramics, Coste House, Calgary

- 1964 Medicine Hat High School, Medicine Hat

- 1971 Alberta College of Art Gallery, travelling to Canadian Guild of Potters, Guild House, Toronto

- 1978 Come Walk With Me, National Exhibition Centre, Medicine Hat (renamed Medicine Hat Museum and Art Gallery in 1980)

- 1980 Lefebvre Galleries Ltd., Edmonton; Medicine Hat Public Library, Medicine Hat

- 1981 Photographic Fantasy, Medicine Hat Public Library, Medicine Hat; Masters Gallery, Calgary

- 1982 Masters Gallery, Calgary; Crescent Heights High School, Medicine Hat

- 1984 Masters Gallery, Calgary

- 1985 Conquest Art Gallery, Calgary; Capital Glass Building, Medicine Hat, organized by Conquest Art Gallery

- 1986 Luke Lindoe, Paintings and Sculpture, The Art Gallery of the South Okanagan, Penticton, B.C.

- 1990 Virginia Christopher Galleries Ltd., Calgary (ceramics)

- 1991 Come Walk With Me, Medicine Hat Museum and Art Gallery; Canadian Art Gallery, Calgary

- 1995 Virginia Christopher Galleries Ltd., Calgary

- 1996 Photographs, Medicine Hat Museum and Art Gallery, Medicine Hat

- 1997 Virginia Christopher Galleries Ltd., Calgary

Collections

Many public and private collections hold his work.[5] Major collections include:[1]

- Alberta Foundation for the Arts, Edmonton

- Alberta College of Art and Design, Calgary

- Alberta House, London, UK

- Bow Valley Industries, Calgary

- Canadian Pacific, Calgary

- Canadian Perspectives, Calgary

- Canadian Utilities Ltd., Calgary

- Carmanah Resources ltd., Calgary

- City of Medicine Hat, Medicine Hat

- Department of External Affairs, Government of Canada, Ottawa

- Everson Museum, Syracuse, New York

- Foothills Hospital, Calgary

- Glenbow Museum, Calgary

- Government House Foundation, Edmonton

- Medicine Hat College, Medicine Hat

- Medicine Hat Museum and Art Gallery, Medicine Hat

- Medicine Hat public Library, Medicine Hat

- Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon

- The Nickle Arts Museum, University of Calgary, Calgary

- PanCanadian Petroleum Ltd., Calgary

- Sapphire Resources Ltd., Calgary

- TransCanada Pipelines Limited, Calgary

- University of Lethbridge Art Gallery, Lethbridge

- The Westaim Corportation, Calgary

- Western Co-operative Fertilizers Ltd., Medicine Hat

Murals and sculpture

Lindoe fulfilled various commissions for murals and sculpture:[1]

- 1947 Greyhound Bus Line Depot, Calgary; portal decoration in conrete relief (destroyed)

- 1948 Imperial Bank of Canada, Calgary; portal relief limestone

- 1949 Alexander Calhoun Public Library, Calgary; engraved brick mural

- 1950 Stampede Corral, Calgary Exhibition and Stampede Board, Calgary; concrete reliefs

- 1950 Kirby Memorial Building, Mount Royal College (Kirby Centre), Calgary

- 1956 St Mary's Cathedral, Calgary; Virgin Mary and Christ Child, exterior cast concrete sculpture, 21 feet high, weighing 7 tons

- 1959 Calgary Allied Arts Council, Canada Council Competition Award, for the Calgary Allied Arts Centre, Calgary; free-standing ceramic block relief (new located at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology, Student Activity Centre)

- 1961 St. John's Church, Lethbridge; brick mosaic facade

- 1961 Dr. Dan MacCharles Memorial, Dan MacCharles Park, Medicine Hat; free-standing ceramic mosaic, mural and fountain

- 1964 Catholic Church, Augusta, Montana; Holy water font and mosaic panel

- 1966 Alberta Provincial Museum and Archives, Edmonton; Museum facade in limestone relief

- 1967 Medicine Hat Public Library, The Canadian Federation of Artists; Medicine Hat Branch Centennial Commission; ceramic sculpture

- 1979–80 Alberta Provincial Treasury Building, Calgary; ceramic mosaic and concrete relief

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Luke Orton Lindoe Biography, Christopher.

- 1 2 Antonelli & Forbes 1978, p. 130.

- 1 2 3 Luke Lindoe RCA, Wilcock and Sax.

- 1 2 Antonelli & Forbes 1978, p. 149.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Luke Lindoe, ArtSask.

- 1 2 3 Sawyer 2013.

- ↑ Henry Bonli, Saskatchewan NAC.

- ↑ Grison 2009.

- 1 2 Antonelli & Forbes 1978, p. 151.

- ↑ Antonelli & Forbes 1978, p. 152.

- 1 2 3 Antonelli & Forbes 1978, p. 175.

- ↑ Pritchard Lerner & Company 2001, p. 30.

Sources

- Antonelli, Marylu; Forbes, Jack (1978-01-01). Pottery in Alberta: The Long Tradition. University of Alberta. ISBN 978-0-88864-023-9. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- Grison, Brian (2009-06-01). "Canada's Walter Dexter: an introduction". Ceramics Art & Perception. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- "Henry Bonli". Saskatchewan NAC. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

- "Luke Lindoe". ArtSask. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- "Luke Lindoe RCA". Wilcock and Sax Gallery. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- "Luke Orton Lindoe Biography". Virginia Christopher Fine Art. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- Pritchard Lerner & Company (2001-02-17). "Notice to Creditors and Claimants". Medicine Hat News. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- Sawyer, Jill (2013). "Luke Lindoe's Life in Clay". Retrieved 2014-08-05.