Lithuanian Liberty League

The Lithuanian Liberty League or LLL (Lithuanian: Lietuvos laisvės lyga) was a dissident organization in the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic and a political party in independent Republic of Lithuania. Established as an underground resistance group in 1978, LLL was headed by Antanas Terleckas.[1] Pro-independence LLL published anti-Soviet literature and organized protest rallies. While it enjoyed limited popularity in 1987–1989, it grew increasingly irrelevant after the independence declaration in 1990.[2] It registered as a political party in November 1995[3] and participated in parliamentary elections without gaining any seats in the Seimas.

First political rallies

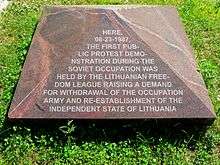

On 23 August 1987, the 48th anniversary of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, LLL organized the first anti-Soviet rally that was not forcibly dispersed by the police.[1] The event tested the limits of glastnost and other liberal Soviet reforms and is often cited as one of the first signs of the Lithuanian independence movement. The rally took place near St. Anne's Church, Vilnius and attracted some 500[4]–1,000[5] participants. While the police monitored the event and reportedly KGB agents took pictures and video of the protesters, the speakers were not interrupted.[4] Demands raised at the event included publication of the Pact, rehabilitation of those deported into Siberia, and greater rights to the Catholic Church.[4] TASS, the official Soviet news agency, labeled the event as a "hate rally" and participants as "aggressive extremists."[4] Other major rallies took place on February 16, 1988, the anniversary of the Act of Independence of Lithuania, and on other sensitive dates from the history of Lithuania.[6]

Removal of Songaila

On 28 September 1988, the League organized an unsanctioned rally to commemorate the German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Demarcation in the Cathedral Square, Vilnius.[7] Activists of more moderate reform movement Sąjūdis clearly distanced themselves from the event. The protesters were met by police and security forces from Minsk.[8] The peaceful protest soon broke out into a 3-hour riot. The protesters threw stones and bottles at the police, which responded by employing batons. Around 25 people were arrested. When the police suddenly left the scene, the peaceful protest continued for another hour and a half.[8] In the early morning of September 29, policemen beat and arrested a group of dissidents on a hunger strike near Vilnius Cathedral.[9] The group, under leadership of Algimantas Andreika, protested the treatment of political prisoners. Outraged by such an unprovoked attack, LLL organized a follow-up rally the same day.[9] Activists of Sąjūdis, including its leader Vytautas Landsbergis, not only participated in the rally but also aggressively questioned the Soviet authorities how such an incident fit into the official program of glastnost and perestroika.[10] It was the first time that Sąjūdis actively supported and advocated on behalf of LLL. The arrested people were released the same day. In the following weeks the activists called for the resignation of Ringaudas Songaila, the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Lithuania.[11] The calls reached Moscow, which approved Songaila's replacement with Algirdas Brazauskas on October 19, 1988.[12]

Relations with Sąjūdis

Due to LLL's uncompromising agenda of full independence,[13] the organization did not enjoy widespread support among the skeptic Lithuanian society.[14] More prominent scientists, artists, and other activists joined Sąjūdis reform movement, which had more moderate agenda and was established with permission from the Soviet authorities. The relationship between the two organizations was complex. While both organizations shared similar goals, LLL was more willing to confront and Sąjūdis preferred to compromise. The League was a "doer" while Sąjūdis was the "talker."[13] Lithuanians abroad described Sąjūdis as "government approved" and LLL as "patriotic."[15] At first Sąjūdis distanced itself from the dissident organization hoping not to tarnish its good reputation and respectable image. In the public opinion, dissidents were discredited, brought fear of arrest or other persecution, and were seen as people without a future.[16] The presence of LLL saved Sąjūdis from the "extremist" label.[14] However, after a violent suppression of one of the LLL's rallies, both organizations grew closer together. When Sąjūdis opted for open membership, dissidents were free to join its ranks and in fact became its left wing.[17] The League played an important role by marking all more sensitive dates from the history of Lithuania with protest rallies or declarations thus stirring up suppressed collective memory and revising official Soviet versions of the events.[18] It also helped to radicalize the independence movement, hastening political reforms and declaration of independence.[2]

Notes and references

- Notes

- 1 2 Kačerauskienė, Aldona (2003-10-03). "Lietuvos laisvės lyga: praeitis ir dabartis". XXI amžius (in Lithuanian). 76 (1180).

- 1 2 Vardys (1997), p. 112

- ↑ Bugajski, Janusz (2002). Political parties of Eastern Europe: a guide to politics in the post-Communist era. M.E. Sharpe. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-56324-676-0.

- 1 2 3 4 Keller, Bill (1987-08-24). "Lithuanians rally for Stalin Victims". The New York Times. p. A1.

- ↑ Laurinavičius (2008), p. 52

- ↑ Ivaškevičius, Arūnas (2008-02-15). "Kaip 1988 m. minėta Vasario 16-oji?" (in Lithuanian). Vilniaus diena and Delfi.lt.

- ↑ Senn (1995), p. 40

- 1 2 Laurinavičius (2008), p. 155

- 1 2 Laurinavičius (2008), p. 157

- ↑ Laurinavičius (2008), pp. 157–158

- ↑ Laurinavičius (2008), pp. 163, 165

- ↑ Laurinavičius (2008), p. 166

- 1 2 Vardys (1997), p. 111

- 1 2 Vardys (1997), p. 110

- ↑ Senn (1995), p. 20

- ↑ Laurinavičius (2008), p. 92

- ↑ Senn (1995), p. 43

- ↑ Budryte, Dovile (2005). Taming nationalism?: political community building in the post-Soviet Baltic States. Post-Soviet politics. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-7546-4281-7.

- References

- Laurinavičius, Česlovas; Vladas Sirutavičius (2008). Sąjūdis: nuo "persitvarkymo" iki kovo 11-osios. Part I. Lietuvos istorija (in Lithuanian). XII. Baltos lankos, Lithuanian Institute of History. ISBN 978-9955-23-164-6.

- Senn, Alfred Erich (1995). Gorbachev's Failure in Lithuania. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-12457-0.

- Vardys, Vytas Stanley; Judith B. Sedaitis (1997). Lithuania: The Rebel Nation. Westview Series on the Post-Soviet Republics. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-1839-4.