List of Presidents of the United States who died in office

During the history of the United States, eight presidents have died in office.[1] Of those eight, four were assassinated and four died of natural causes.[2] In all eight cases, the Vice President of the United States took over the office of presidency as part of the United States presidential line of succession.[3]

William Henry Harrison holds the record for shortest term served, holding the office of presidency for 31 days before dying. Harrison was the first president to die while in office when he caught pneumonia and died on April 4, 1841.[4] On July 9, 1850, Zachary Taylor died from acute gastroenteritis.[5] Abraham Lincoln was the first president to be assassinated. He was shot behind his left ear by John Wilkes Booth on April 14, 1865.[6] Sixteen years later, on September 19, 1881, President James A. Garfield was assassinated by Charles J. Guiteau.[7] Nearly twenty years after that, President William McKinley died from complications after being shot twice by Leon Czolgosz.[8] President Warren G. Harding suffered a heart attack, and died on August 2, 1923.[9] On April 12, 1945, Franklin Delano Roosevelt collapsed and died as a result of a cerebral hemorrhage.[10] The most recent president to die in office was John F. Kennedy, who was assassinated with two rifle shots on November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas.[11]

1841: William Henry Harrison

On March 26, 1841, William Henry Harrison became ill with a cold. According to the prevailing medical misconception of that time, it was believed that his illness was directly caused by the bad weather at his inauguration; however, Harrison's illness did not arise until more than three weeks after the event. The cold worsened, rapidly turning to pneumonia and pleurisy.[12] He sought to rest in the White House, but could not find a quiet room because of the steady crowd of office seekers. His extremely busy social schedule made any rest time scarce.[13]

Harrison's doctors tried cures, applying opium, castor oil, leeches, and Virginia snakeroot. But the treatments only made Harrison worse, and he became delirious. He died nine days after becoming ill,[14] at 12:30 am on April 4, 1841, of right lower lobe pneumonia, jaundice, and overwhelming septicemia. He was the first United States president to die in office. His last words were to his doctor, but assumed to be directed at John Tyler, "Sir, I wish you to understand the true principles of the government. I wish them carried out. I ask nothing more." Harrison served the shortest term of any American president: March 4 – April 4, 1841, 30 days, 12 hours, and 30 minutes.[15][16]

Harrison's funeral took place in the Wesley Chapel in Cincinnati, Ohio, on April 7, 1841.[17] His original interment was in the public vault of the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C. He was later buried in North Bend, Ohio. The William Henry Harrison Tomb State Memorial was erected in his honor.[18]

1850: Zachary Taylor

The cause of Zachary Taylor's death has not been fully established.[19] On July 4, 1850, Taylor was known to have consumed copious amounts of ice water, cold milk, green apples, and cherries after attending holiday celebrations and the laying of the cornerstone of the Washington Monument.[20] That same evening, he became severely ill with an unknown digestive ailment. Doctors used popular treatments of the time. Taylor died in the White House at 10:35 p.m. on July 9, five days after becoming ill.[21] Contemporary reports listed the cause of death as "bilious diarrhea, or a bilious cholera".[22]

Almost immediately after his death, rumors began to circulate that Taylor was poisoned by pro-slavery Southerners, and similar theories persisted into the twentieth century.[23] The remains were exhumed and transported to the Office of the Kentucky Chief Medical Examiner on June 17, 1991. Neutron activation analysis conducted at Oak Ridge National Laboratory revealed no evidence of poisoning, as arsenic levels were too low.[24][25] The analysis concluded Taylor had contracted "cholera morbus, or acute gastroenteritis", as Washington had open sewers, and his food or drink may have been contaminated.[26]

Taylor was interred in the Public Vault of the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C. from July 13, 1850 to October 25, 1850. (It was built in 1835 to hold remains of notables until either the grave site could be prepared or transportation arranged to another city.) His body was transported to the Taylor Family plot where his parents are buried, on the old Taylor homestead plantation known as 'Springfield' in Louisville, Kentucky.[27]

1865: Abraham Lincoln

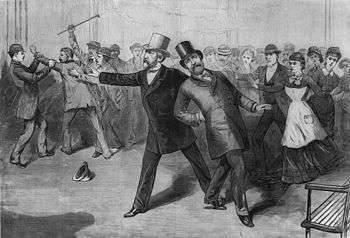

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln took place on Good Friday,[28] on April 14, 1865, as the American Civil War was drawing to a close. The assassination occurred five days after the commanding General of the Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee, surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln was the first American president to be assassinated,[29] though an unsuccessful attempt had been made on Andrew Jackson 30 years before in 1835.[30]

The assassination of Lincoln was planned and carried out by the well-known stage actor John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer, vehement in his denunciation of Lincoln, and a strong opponent of the abolition of slavery in the United States.[31] Booth and a group of co-conspirators originally plotted to kidnap Lincoln, but later planned to kill him, Vice President Andrew Johnson, and Secretary of State William H. Seward in a bid to help the Confederacy's cause.[32]

Lincoln was shot once in the back of his head while watching the play Our American Cousin with his wife Mary Todd Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C. at around 10:15 pm on the night of April 14, 1865.[33] An army surgeon who happened to be at Ford's, Doctor Charles Leale, assessed Lincoln's wound as mortal.[34] The President was then carried across the street from the theater to the Petersen Boarding House,[35] where he died the next morning at 7:22 am on April 15 without regaining consciousness.[36]

1881: James A. Garfield

The assassination of James A. Garfield took place in Washington, D.C. on July 2, 1881. Garfield was shot by Charles J. Guiteau at 9:30 am, less than four months into Garfield's term as the 20th President of the United States. Garfield died eleven weeks later on September 19, 1881. His Vice President, Chester A. Arthur, succeeded Garfield as President. Garfield also lived the longest after the shooting, compared to other Presidents. Garfield was scheduled to leave Washington on July 2, 1881 for his summer vacation.[39] On that day, Guiteau lay in wait for the President at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad station, on the southwest corner of present-day Sixth Street and Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, D.C.[40]

President Garfield came to the Sixth Street Station on his way to his alma mater, Williams College, where he was scheduled to deliver a speech. Garfield was accompanied by two of his sons, James and Harry, and Secretary of State Blaine. Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln waited at the station to see the President off.[41] Garfield had no bodyguard or security detail; with the exception of Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War, early U.S. presidents never used any guards.[42]

As President Garfield entered the waiting room of the station Guiteau stepped forward and pulled the trigger from behind at point-blank range. "My God, what is that?" Garfield cried out, flinging up his arms. Guiteau fired again and Garfield collapsed.[43] One bullet grazed Garfield's shoulder; the other hit him in the back, passing the first lumbar vertebra but missing the spinal cord before coming to rest behind his pancreas.[44]

Garfield, conscious but in shock, was carried to an upstairs floor of the train station.[45] One bullet remained lodged in his body, but doctors could not find it.[46] Young Jim Garfield and James Blaine both broke down and wept. Robert Todd Lincoln, deeply upset and thinking back to the death of his father, said "How many hours of sorrow I have passed in this town."[46]

Garfield was carried back to the White House. Although doctors told him that he would not survive the night, the President remained conscious and alert.[47] The next morning his vital signs were good and doctors began to hope for recovery.[48] A long vigil began, with Garfield's doctors issuing regular bulletins that the American public followed closely throughout the summer of 1881.[49][50] His condition fluctuated. Fevers came and went. Garfield struggled to keep down solid food and spent most of the summer eating little, and that only liquids.[51]

Garfield had been a regular visitor to shore town of Long Branch, NJ, one of the nation’s premier summer vacation spots until World War I. In early September, it was decided to bring him to Elboron, a quiet beach town just to the south of Long Branch, in hopes that the beach air would help him recover. When they heard that the president was being brought to their town, local citizens built more than half a mile of tracks in less than 24 hours, enabling Garfield to be brought directly to the door of the oceanfront Franklyn cottage, rather than being moved by carriage from the local Elberon train station. However, Garfield died 12 days later. A granite marker on Garfield Rd identifies the former site of the cottage, which was demolished in 1950.

Chester Arthur was at his home in New York City on the night of September 19, when word came that Garfield had died. After first getting the news, Arthur said "I hope—my God, I do hope it is a mistake." But confirmation by telegram came soon after. Arthur took the presidential oath of office, administered by a New York Supreme Court judge, then left for Long Branch to pay his respects before going on to Washington.[52] Garfield's body was taken to Washington, where it lay in state for two days in the Capitol Rotunda before being taken to Cleveland, where the funeral was held on September 26.[53]

When the tracks that had been hastily built to the Franklyn cottage were later torn up, actor Oliver Byron bought the wooden ties, and had local carpenter William Presley build them into a small tea house, in commemoration of the president. The red & white (originally red, white & blue) "Garfield Tea House" still survives, resting a couple of blocks away from the site of the cottage on the grounds of the Long Branch Historical Museum, a former Episcopal Church. The church is nicknamed "The Church of the Presidents", as it had been attended by, in addition to Garfield, Presidents Chester A. Arthur, Ulysses S. Grant, Benjamin Harrison, Rutherford Hayes, William McKinley, and Woodrow Wilson, during their own visits to Long Branch.

1901: William McKinley

William McKinley was assassinated on September 6, 1901, inside the Temple of Music on the grounds of the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. McKinley was shaking hands with the public when he was shot by Leon Czolgosz, an anarchist. The President died eight days later on September 14 from gangrene caused by the bullet wounds.[8]

McKinley had been elected for a second term in 1900.[54] He enjoyed meeting the public, and was reluctant to accept the security available to his office.[55] The Secretary to the President, George B. Cortelyou, feared an assassination attempt would take place during a visit to the Temple of Music, and twice took it off the schedule. McKinley restored it each time.[56]

Czolgosz had lost his job during the economic Panic of 1893 and turned to anarchism, a political philosophy whose adherents had killed foreign leaders.[57] Regarding McKinley as a symbol of oppression, Czolgosz felt it was his duty as an anarchist to kill him.[58] Unable to get near McKinley during the earlier part of the presidential visit, Czolgosz shot McKinley twice as the President reached to shake his hand in the reception line at the temple. One bullet grazed McKinley; the other entered his abdomen and was never found.[8]

McKinley initially appeared to be recovering, but took a turn for the worse on September 13 as his wounds became gangrenous, and died early the next morning; Vice President Theodore Roosevelt succeeded him. Roosevelt was hiking near the top of Mt. Marcy, in New York State's Adirondack region, when a runner located him to convey the bad news.[59] After McKinley's murder, for which Czolgosz was put to death in the electric chair, the United States Congress passed legislation to officially charge the Secret Service with the responsibility for protecting the president.[60]

1923: Warren G. Harding

Warren G. Harding died from a sudden heart attack in his hotel suite while visiting San Francisco at around 7:35 p.m. on August 2, 1923. His death quickly led to theories that he had been poisoned[61] or committed suicide. Rumors of poisoning were fueled, in part, by a book called The Strange Death of President Harding, in which the author (convicted criminal, former Ohio Gang member, and detective Gaston Means, hired by Mrs. Harding to investigate Warren Harding and his mistress) suggested that Mrs. Harding had poisoned her husband after learning of his infidelity. Mrs. Harding's refusal to allow an autopsy on President Harding only added to the speculation. According to the physicians attending Harding, however, the symptoms in the days prior to his death all pointed to congestive heart failure. Harding's biographer, Samuel H. Adams, concluded that "Warren G. Harding died a natural death which, in any case, could not have been long postponed".[62]

Immediately after President Harding's death, Mrs. Harding returned to Washington, D.C., and briefly stayed in the White House with President and First Lady Coolidge. For a month, former First Lady Harding gathered and destroyed by fire President Harding's correspondence and documents, both official and unofficial. Upon her return to Marion, Mrs. Harding hired a number of secretaries to collect and burn President Harding's personal papers. According to Mrs. Harding, she took these actions to protect her husband's legacy. The remaining papers were held and kept from public view by the Harding Memorial Association in Marion.[63]

1945: Franklin D. Roosevelt

On March 29, 1945, Franklin D. Roosevelt went to the Little White House at Warm Springs, Georgia, to rest before his anticipated appearance at the founding conference of the United Nations. On the afternoon of April 12, Roosevelt said, "I have a terrific pain in the back of my head." He then slumped forward in his chair, unconscious, and was carried into his bedroom. The president's attending cardiologist, Dr. Howard Bruenn, diagnosed a massive cerebral hemorrhage (stroke).[64] At 3:35 pm that day, Roosevelt died without regaining consciousness. As Allen Drury later said, “so ended an era, and so began another.” After Roosevelt's death, an editorial by The New York Times declared, "Men will thank God on their knees a hundred years from now that Franklin D. Roosevelt was in the White House".[65]

In his later years at the White House, when Roosevelt was increasingly overworked, his daughter Anna Roosevelt Boettiger had moved in to provide her father companionship and support. Anna had also arranged for her father to meet with his former mistress, the now widowed Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd. A close friend of both Roosevelt and Mercer who was present, Elizabeth Shoumatoff, rushed Mercer away to avoid negative publicity and implications of infidelity. When Eleanor heard about her husband's death, she was also faced with the news that Anna had been arranging these meetings with Mercer and that Mercer had been with Franklin when he died.[66]

On the morning of April 13, Roosevelt's body was placed in a flag-draped coffin and loaded onto the presidential train. After a White House funeral on April 14, Roosevelt was transported back to Hyde Park by train, guarded by four servicemen, one each from the Army, Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard. As was his wish, Roosevelt was buried in the Rose Garden of the Springwood estate, the Roosevelt family home in Hyde Park on April 15. Eleanor died in November 1962 and was buried next to him.[67]

Roosevelt's death was met with shock and grief[68] across the U.S. and around the world. His declining health had not been known to the general public. Roosevelt had been president for more than 12 years, longer than any other person, and had led the country through some of its greatest crises to the impending defeat of Nazi Germany and within sight of the defeat of Japan as well.

Less than a month after his death, on May 8, the war in Europe ended. President Harry S. Truman, who turned 61 that day, dedicated Victory in Europe Day and its celebrations to Roosevelt's memory, and kept the flags across the U.S. at half-staff for the remainder of the 30-day mourning period. In doing so, Truman said that his only wish was "that Franklin D. Roosevelt had lived to witness this day."[69]

1963: John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy was assassinated at 12:30 p.m. Central Standard Time (18:30 UTC) on Friday, November 22, 1963, in Dealey Plaza, Dallas, Texas.[70][71] Kennedy was fatally shot while traveling with his wife Jacqueline, Texas Governor John Connally, and the latter's wife Nellie, in a Presidential motorcade. The ten-month investigation by the Warren Commission of 1963–1964 concluded that President Kennedy was assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald and that Oswald had acted entirely alone. It also concluded that Jack Ruby acted alone when he killed Oswald before he could stand trial. Nonetheless, polls conducted from 1966 to 2004 found that as many as 80 percent of Americans have suspected that there was a plot or cover-up.[72][73]

Most current John F. Kennedy assassination conspiracy theories put forth a criminal conspiracy involving parties as varied as the CIA, the Mafia, anti-Castro Cuban exile groups, the military industrial complex, sitting Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Cuban President Fidel Castro, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, the KGB, or some combination of those entities.[74] In an article published prior to the 50th anniversary of Kennedy's assassination, author Vincent Bugliosi estimates that a total of 42 groups, 82 assassins, and 214 people have been accused in conspiracy theories challenging the "lone gunman" theory.[75]

See also

References

- ↑ Brunner, Borgna. "Presidential Trivia". Info Please. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ↑ "Presidential and Vice Presidential Succession: Overview and Current Legislation". Internet Public Library. Retrieved December 22, 2008.

- ↑ Neale, Thomas H. (September 27, 2004). "Presidential and Vice Presidential Succession: Overview and Current Legislation" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ↑ "Harrison's Inauguration". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ↑ "Zachary Taylor". White House. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ↑ "Assassination of President Abraham Lincoln". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ↑ MacGowen, Douglas. "Charles J. Guiteau". Crime Library. Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- 1 2 3 Leech 594-600

- ↑ "Harding a Farm Boy Who Rose by Work". New York Times. August 3, 1923. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ↑ "Franklin D. Roosevelt". White House. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ↑ "The President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection". National Archives. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ↑ Cleaves 152

- ↑ "Harrison's Inauguration (Reason): American Treasures of the Library of Congress". Library of Congress. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ↑ Cleaves 160

- ↑ "President Harrison Dies – April 4, 1841". Events in Presidential History. Miller Center, University of Virginia. 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2009.

- ↑ ed.: Robert A. Diamond ... Major contributors: Rhodes Cook ... (1976). Congressional Quarterly's Guide to U.S. Elections. Congressional Quarterly Inc. p. 492. ISBN 978-0-87187-072-8.

- ↑ "William Henry Harrison". White House Historical Association. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Harrison Tomb". Ohio Historical Society. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ↑ Parenti, Michael (September 1999). History as Mystery. City Light Books. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-87286-357-6.

- ↑ Eisenhower, John S.D. (2008). Zachary Taylor The American Presidents. Macmillan. pp. 132–3. ISBN 978-0805082371.

- ↑ Bauer, pp. 314–316.

- ↑ "Death of the President of the United States". Boston Daily Evening Transcript. July 10, 1850. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ↑ Willard and Marion (2010). Killing the President. p. 188.

- ↑ Marriott, Michel (June 27, 2011). "Verdict In: 12th President Was Not Assassinated". The New York Times. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ↑ "President Zachary Taylor and the Laboratory: Presidential Visit from the Grave". Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Retrieved November 2, 2010.

- ↑ Sampas, Jim (July 4, 1991). "Scandal and the Heat Did Zachary Taylor In". The New York Times. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ↑ Christine Quigley (2005). The Corpse: A History. McFarland & Company. p. 134. ISBN 0786424494.

- ↑ "Good Friday, 1865: Lincoln's Last Day". NPHR STAFF. 2008-02-18. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ↑ "Lincoln Shot at Ford's Theater". Library of Congress. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ↑ Wilentz, Sean. Andrew Jackson (2005), p. 8, 35.

- ↑ "The murderer of Mr. Lincoln" (PDF). The New York Times. April 21, 1865.

- ↑ Hamner, Christopher. "Booth's Reason for Assassination." Teachinghistory.org. Accessed 12 July 2011.

- ↑ Phillip B. Kunhardt Jr.; Phillip Kunhardt III; Peter Kunhardt (1992). Lincoln: An Illustrated Biography. New York: Gramercy Books. p. 346. ISBN 0-517-20715-X.

- ↑ James Swanson (2006). Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer. Harper Collins. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-06-051849-3.

- ↑ "Henry Safford". rogerjnorton.com. Archived from the original on June 1, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ↑ Richard A. R. Fraser, MD (February–March 1995). "How Did Lincoln Die?". American Heritage. 46 (1).

- ↑ Lynne Vincent Cheney (October 1975). "Mrs. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper". American Heritage Magazine. 26 (6). Archived from the original on November 6, 2009. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ↑ "The attack on the President's life". Library of Congress. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ↑ Peskin 581

- ↑ George Stinson Conwell. The life, speeches, and public services of James A. Garfield, twentieth President of the United States : including an account of his assassination, lingering pain, death and burial. Portland, Maine. p. 349. OCLC 2087548.

- ↑ Vowell 160

- ↑ Peskin 593

- ↑ Peskin 596

- ↑ Millard 189, 312

- ↑ Peskin 596–597

- 1 2 Peskin 597

- ↑ Peskin 598

- ↑ Peskin 599

- ↑ Peskin 600

- ↑ Vowell 124

- ↑ Peskin 601

- ↑ Peskin 608

- ↑ Peskin 608–609

- ↑ Rauchway, Eric (2004). Murdering McKinley: The Making of Theodore Roosevelt's America. New York: Hill and Wang. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-8090-1638-9.

- ↑ Leech 561-62

- ↑ Leech 584

- ↑ Miller 56-60

- ↑ Miller 301–302

- ↑ Morgan, H. Wayne (2003). William McKinley and His America (revised ed.). Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press. p. 402. ISBN 978-0-87338-765-1.

- ↑ Bumgarner, Jeffrey (2006). Federal Agents: The Growth of Federal Law Enforcement in America. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-275-98953-8.

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Jones MD; Joni L. Jones PhD, RN. "Presidential Stroke: United States Presidents and Cerebrovascular Disease (Warren G. Harding))". Journal CMEs. CNS Spectrums (The International Journal of Neuropsychiatric Medicine). Retrieved July 20, 2011. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Adams (1939, 1964), Incredible Era, pp. 377–384

- ↑ Russell (April 1963), The Four Mysteries Of Warren Harding

- ↑ Jones, Jeffrey M.; Joni L. Jones PhD, RN. "Presidential Stroke: United States Presidents and Cerebrovascular Disease (Franklin D. Roosevelt)". Journal CMEs. CNS Spectrums (The International Journal of Neuropsychiatric Medicine). Retrieved July 20, 2011. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ "Person of the Century Runner-Up: Franklin Delano Roosevelt". Time. March 1, 2000. Archived from the original on November 10, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ↑ William D. Pederson (2011). A Companion to Franklin D. Roosevelt. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 1444395173.

- ↑ Margaret Prentice Hecker (2010). Leslie Alexander, ed. "Roosevelt, Eleanor". Encyclopedia of African American History. ABC-CLIO. 1: 999. ISBN 1851097694.

- ↑ Video: Allies Overrun Germany (1945). Universal Newsreel. 1945. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- ↑ McCullough 345, 381

- ↑ Warren Commission Testimony of Nellie Connally, vol. 4, p. 147.

- ↑ Warren Commission Testimony of John B. Connally, vol. 4, pp. 131–132.

- ↑ Gary Langer (November 16, 2003). "John F. Kennedy's Assassination Leaves a Legacy of Suspicion" (PDF). ABC News. Retrieved May 16, 2010.

- ↑ Jarrett Murphy, 40 Years Later: Who Killed JFK?, CBS News, November 21, 2003.

- ↑ Summers, Anthony (2013). "Six Options for History". Not in Your Lifetime. New York: Open Road. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-4804-3548-3.

- ↑ "One JFK conspiracy theory that could be true - CNN.com". CNN. November 18, 2013.

Bibliography

- Bauer, K. Jack (1985). Zachary Taylor: Soldier, Planter, Statesman of the Old Southwest. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-1237-2.

- Cleaves, Freeman (1939). Old Tippecanoe: William Henry Harrison and His Time. New York, NY: C. Scribner's Sons.

- Leech, Margaret (1959). In the Days of McKinley. New York: Harper and Brothers. pp. 594–600. OCLC 456809.

- McCullough, David (1992). Truman. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-86920-5.

- Millard, Candice (2011). Destiny of the Republic. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-53500-7.

- Miller, Scott (2011). The President and the Assassin. New York: Random House. pp. 56–60. ISBN 978-1-4000-6752-7.

- Peskin, Allan (1978). Garfield. Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-210-2.

- Vowell, Sarah (2005). Assassination Vacation. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-6003-1.

External links

- The Mortal Presidency (Shapell Manuscript Foundation)