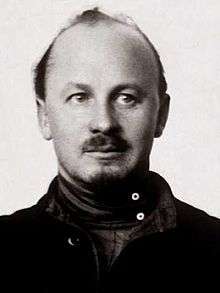

Lev Chernyi

| Lev Chernyi Лев Чёрный | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Pavel Dimitrievich Turchaninov Birth date unknown |

| Died | September 21, 1921 |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Occupation | Poet, activist |

| Known for | Revolutionary anarchism |

Lev Chernyi (Russian: Лев Чёрный; IPA: [ˈlʲɛf ˈtɕɵrnɨj]; died September 21, 1921) was a Russian individualist anarchist theorist, activist and poet, and a leading figure of the Third Russian Revolution.[1] In 1917, Chernyi was released from his political imprisonment by the Imperial Russian regime, and swiftly became one of the leading figures in Russian anarchism. After strongly denouncing the new Bolshevik government in various anarchist publications and joining several underground resistance movements, Chernyi was arrested by the Cheka on a charge of counterfeiting and in 1921 was executed without trial.

Early life, philosophy and imprisonment

Chernyi was born Pavel Dimitrievich Turchaninov (Russian: Па́вел Дми́триевич Турчани́нов; IPA: [ˈpavʲɪl ˈdmʲitrʲɪjɪvʲɪt͡ɕ tʊrt͡ɕɐˈnʲinəf]) to an army colonel father.[2] A "déclassé intellectual" whom anarchist historian Paul Avrich compares with Volin, Chernyi advocated a Nietzschean overthrow of the values of bourgeois Russian society, and rejected the voluntary communes of anarcho-communist Peter Kropotkin as a threat to the freedom of the individual.[2][3][4] Chernyi advocated the "free association of independent individuals" in a book titled Associational Anarchism and published in 1907.[4] Scholars including Avrich and Allan Antliff have interpreted this vision of society to have been greatly influenced by the individualist anarchists Max Stirner, and Benjamin Tucker.[5] Subsequent to the book's publication, Chernyi was imprisoned in Siberia under the Russian Czarist regime for his revolutionary activities.[1]

Return to Moscow and opposition to the Bolsheviks

On his return from Siberia in 1917, Chernyi enjoyed great popularity among Moscow workers as a lecturer, and was at this time one of Russia's leading individualist anarchists[2] and one of anarchism's main ideologues.[6] He was the Secretary and leading theorist of the Moscow Federation of Anarchist Groups, which was formed in March 1917 after the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and was primarily concerned with disseminating propaganda to Moscow's poorer classes.[2][5]

A personal acquaintance of Lev Kamenev and other leading Bolsheviks, Chernyi denounced the nascent Russian Soviet Republic at a rally on March 5, 1918, declaring that for anarchists, the socialist state was as much an enemy as its bourgeois predecessor and promising to "paralyze the governmental mechanism".[6] A vociferous advocate of seizing private homes,[2] Chernyi agitated against the state in the pages of Anarkhiia, the anarchist weekly newspaper, proposing increasingly detailed means of decentralized production and "complete absence of internal power structures".[6] In the spring of 1918, the anarchist groups within the Moscow Federation formed armed detachments in reaction to the growing repression of all resistance and free expression.[1] These were the Black Guards, precursors to the anarchist Black Army which fought the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War. On the night of April 11, the Cheka (Soviet secret police) raided a building occupied by the Moscow Federation, with the official aim of arresting and charging "robber bands" in the anarchist ranks.[5] They were met with armed resistance by the Black Guards and in the ensuing battle, approximately forty anarchists were killed or wounded and about five hundred were imprisoned.[1]

Arrest and execution

Having helped establish an underground group in 1918, Chernyi joined another group called the Underground Anarchists the following year.[7] The organization, which had been founded by Kazimir Kovalevich and Piotr Sobalev, published two issues of an incendiary broadsheet denouncing the Communist dictatorship as the worst tyranny in human history.[1] On September 25, 1919, together with a number of leftist social revolutionaries, the Underground Anarchists bombed the headquarters of the Moscow Committee of the Communist Party during a plenary meeting. Twelve Communists were killed and fifty-five others were wounded, including eminent Bolshevik theorist and Pravda editor Nikolai Bukharin.[7] Chernyi was detained along with Fanya Baron on a counterfeiting charge.[8] In August 1921, the Moscow Izvestia published an official report announcing that ten "anarchist bandits", among them Chernyi, had been shot without hearing or trial. However, historian of anarchism Paul Avrich contends that Chernyi was executed in September of that year rather than August.[1] Although he was not personally involved in the bombing of the Communist Party headquarters, Chernyi was, because of his association with the Underground Anarchists, a likely candidate for a frameup. The Communists refused to turn over his body to his family for burial, and rumors persisted that he had in fact died of torture.[1]

Bibliography

- Novoe napravlenie v anarkhizme: assotsiatsionnyi anarkhizm. 2nd edn, New York, 1923.

- O klassakh. Moscow, 1924.

Related pages

- Individualist anarchism in Europe

- List of anarchist poets

- One of the people who visited his lectures was Gerard Shelley

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Phillips, Terry (Fall 1984). "Lev Chernyi". The Match! (79). Retrieved 2008-03-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Avrich 2006, p. 180

- ↑ Avrich 2006, p. 254

- 1 2 Chernyi, Lev (1923) [1907]. Novoe Napravlenie v Anarkhizme: Asosiatsionnii Anarkhism (Moscow; 2nd ed.). New York.

- 1 2 3 Antliff, Allan (2007). "Anarchy, Power, and Poststructuralism" (PDF). SubStance. 36 (113): 56–66. doi:10.1353/sub.2007.0026. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

- 1 2 3 Cooke, Catherine (1999). "Alexei Gan and the Moscow Anarchists". In Leach, Neil. Architecture and Revolution. New York: Routledge. pp. 25–37. ISBN 0-415-13914-7.

- 1 2 Avrich 2006, p. 188

- ↑ Polenberg, Richard (1999). Fighting Faiths: the Abrams Case, the Supreme Court and Free Speech. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 350. ISBN 0-8014-8618-1.

References

- Avrich, Paul (2006). The Russian Anarchists. Stirling: AK Press. ISBN 1-904859-48-8.