Karlovy Vary

| Karlovy Vary | |||

| Carlsbad | |||

| Town | |||

A Bird's-eye view of Karlovy Vary | |||

|

|||

| Country | Czech Republic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Karlovy Vary | ||

| District | Karlovy Vary | ||

| Rivers | Ohře, Teplá, Rolava | ||

| Elevation | 447 m (1,467 ft) | ||

| Coordinates | CZ 50°14′N 12°52′E / 50.233°N 12.867°ECoordinates: CZ 50°14′N 12°52′E / 50.233°N 12.867°E | ||

| Area | 59.10 km2 (23 sq mi) | ||

| Population | 49,781 (As of 2015[1]) | ||

| Density | 842/km2 (2,181/sq mi) | ||

| Founded around | 1350 | ||

| Mayor | Ing. Petr Kulhánek | ||

| Timezone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| - summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| Postal code | 360 01 | ||

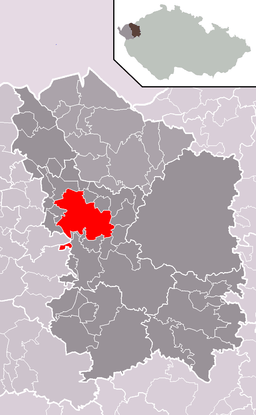

Location in the Czech Republic

| |||

Location in Karlovy Vary District

| |||

| Wikimedia Commons: Karlovy Vary | |||

| Statistics: statnisprava.cz | |||

| Website: www.karlovyvary.cz | |||

Karlovy Vary or Carlsbad (Czech pronunciation: [ˈkarlovɪ ˈvarɪ]; German: Karlsbad) is a spa town situated in western Bohemia, Czech Republic, on the confluence of the rivers Ohře and Teplá, approximately 130 km (81 mi) west of Prague (Praha). It is named after Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia, who founded the city in 1370. It is historically famous for its hot springs (13 main springs, about 300 smaller springs, and the warm-water Teplá River). It is the most visited spa town in the Czech Republic.[2]

History

An ancient late Bronze Age fortified settlement was found in Drahovice. A Slavic settlement in Karlovy Vary is documented by findings in Tašovice and Sedlec. People lived in the close proximity of later Karlovy Vary as far back as the 13th century and they must have been aware of the curative effects of close thermal springs.[3]

Around 1350, Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor organized an expedition into the forests surrounding modern-day Karlovy Vary during a stay in Loket. On the site of a spring, he established a spa called the Horké Lázně u Lokte (Hot Spas at Loket). The location was subsequently renamed after him once he had acclaimed the healing power of the hot springs, at least according to legend. Charles IV granted the city privileges on 14 August 1370. Earlier settlements can be also found in the outskirts of today's city.

Due to publications produced by physicians such as David Becher and Josef von Löschner, the city developed into a famous spa resort in the 19th century and was visited by many members of European aristocracy as well as celebrities from many fields of endeavor. It became more popular after railway lines to Cheb and Prague were completed in 1870.

The number of visitors rose from 134 families in the 1756 season to 26,000 guests annually at the end of the 19th century. By 1911, that figure had reached 71,000, but the outbreak of World War I in 1914 greatly disrupted the tourism on which the town depended.

A political action of great importance took place in the town in 1819: the issuance of the Carlsbad Decrees. Initiated by the Austrian Minister of State Klemens von Metternich, they were intended to implement anti-liberal censorship within the German Confederation.

At the end of World War I in 1918, the large German-speaking population of Bohemia was incorporated into the new state of Czechoslovakia in accordance with the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919). As a result, the German-speaking majority of Karlovy Vary protested. A demonstration on 4 March 1919 passed peacefully, but later that month, six demonstrators were killed by Czech troops after a demonstration turned unruly.[4]

In 1938, the majority German-speaking areas of Czechoslovakia, known as the Sudetenland, became part of Nazi Germany according to the terms of the Munich Agreement. These areas included Karlovy Vary. After World War II, in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement, the vast majority of the people of Karlovy Vary were forcibly expelled from the city because of their German ethnicity. In accordance with the Beneš decrees, their property was confiscated without compensation.

Since the end of Communist rule in Czechoslovakia in 1989 and the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, there has been a steady increase of a Russian business presence in Karlovy Vary.

Panoramic views

Population

| Year | 1869 | 1900 | 1930 | 1939 | 1947 | 1961 | 1991 | 2001 | 2008 | 2013 | 2014 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population[5][6] | 14,185 | 42,653 | 54,652 | 53,339 | 31,322 | 50,034 | 56,291 | 53,857 | 53,708 | 53,737 | 49,864 | 49,326 |

In 2012, foreigners were around 7% of the population of the Karlovy Vary region. After Prague, this is the highest proportion in the Czech Republic. The largest group of foreigners were Vietnamese, followed by Germans, Russians and Ukrainians.[7]

Transport

Local buses and cable cars take passengers to most areas of the city. The city can be reached from other locations by inter-city buses and by train. The city is connected by expressway R6. International Karlovy Vary Airport is located 4.5 km south-east from the city, at the nearby village of Olšová Vrata.

Churches

- Catholic Church of St. Mary Magdalene – built by Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer in 1737

- Orthodox Church of Saints Peter and Paul – 1898

- Protestant Church of Saints Peter and Paul – 1856

- Church of St. Anne – 1745

- Greek Catholic St. Andrew Cemetery Church – 1500

- Methodist Church of Saint Luke – 1877

- St. Linharta ruins from 13th century

Culture

In the 19th century, Karlovy Vary became a popular tourist destination, especially known for international celebrities who visited for spa treatment. The city is also known for the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, which is one of the oldest in the world and one of Europe's major film events. It is also known for the popular Czech liqueur Becherovka and the production of the famous glass manufacturer Moser Glass, which is located in Karlovy Vary. The famous Karlovarské oplatky (Carlsbad wafers) originated in the city in 1867. It has also lent its name to the delicacy known as "Carlsbad plums". These plums (usually quetsch) are candied in hot syrup, then halved and stuffed into dried damsons; this gives them a very intense flavour.

The city has been used as the location for a number of film-shoots, including the 2006 films Last Holiday and box-office hit Casino Royale, both of which used the city's Grandhotel Pupp in different guises.

People

Native

- Walter Becher

- Stanislav Birner

- Tomáš Borek

- Zbyněk Brynych

- Karel Dobrý

- Tomáš Došek

- Karl Hermann Frank, Nazi official

- Princess Michael of Kent

- Petr Kopfstein, aerobatics pilot

- Rudolf Křesťan

- Rick Lanz

- Johann Josef Loschmidt (15 March 1821 – 8 July 1895), Austrian scientist.

- Ludmila Peterková

- Károly Pulváry (1907–1999), Hungarian designer[8]

- Karel Rada

- Georg Riedel

- Josef Řihák

- Walter Serner, dadaist

- Hana Soukupová, supermodel

- Milan Šperl

- Karin Stoiber, née Buch (born 1943, Bochov), former First Lady of Bavaria

- Jana Sýkorová

- Tomáš Vokoun, goaltender of the NHL Pittsburgh Penguins

- Ignaz Ziegler

Notable people associated with Karlovy Vary

- Peter I of Russia visited Karlovy Vary in 1711[9]

- Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founder of the Republic of Turkey, as well as its first President, visited Karlsbad in 1918 for spa treatments[10]

- František Běhounek, scientist and novelist, died here

- Johann Wolfgang Goethe,[11] German poet, novelist, philosopher, scientist

- Princess Michael of Kent (born Baroness Marie Christine Agnes Hedwig Ida von Reibnitz), a member of the British Royal Family, was born in January 1945, prior to the expulsion of the German population later that year.

- Adalbert Stifter, Austrian writer

- Ludwig van Beethoven, composer, came for spa treatments. He and the poet Goethe would take walks together, much to the delight of the local people.

- Fryderyk Chopin, composer, and his parents met for the last time during a holiday in Karlsbad, August/September 1835.

- Anthony J. Drexel, senior partner of Drexel, Morgan & Co. (JPMorgan, today) and founder of Drexel University, died in Karlsbad in 1893 while spending the summer there for his health.

- Vladimir Voronin, former president or Republic of Moldova, visits Karlovy Vary every year for spa treatments.

- James Ogilvy, 7th Earl of Findlater, Scottish noble and an accomplished amateur landscape architect and philanthropist

- Ivan Turgenev, the Russian novelist, visited Karlsbad on numerous occasions for its healing waters.

- Jean de Carro, Swiss physician, published the Almanach de Carlsbad

- Gerda Mayer, English poet, born in Karlsbad

- Saint Diddlemus Maximus, born 769 AD. He was part of a Christian movement proclaiming the benefits of cultivating buckwheat as a staple crop in the region. He is the patron saint of grain, in particular buckwheat. Martyred December 23,793

- Baron Gustaf Mannerheim (1867-1951), Marshal of Finland, President of the Finnish Republic in 1944-46.

Gallery

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Karlovy Vary. |

-

Outdoor pool with mineral water in winter

-

Vřídelní street, above sets of Jeanna de Carro

-

Area over Vřídelní street

-

Aerial View of Karlovy Vary

-

Street view of Karlovy Vary

-

Karlovy Vary Airport

-

City Opera House of Karlovy Vary

-

A bottle of Becherovka

-

Park Colonnade

-

Plaque indicating the building where Mustafa Kemal Atatürk resided while in Karlovy Vary

International relations

Carlsbad, New Mexico, United States[12] (after which Carlsbad Caverns National Park is named), Carlsbad, California, USA [13] Carlsbad Springs, Ontario, Canada, and Carlsbad, Texas, USA, take their names from Karlovy Vary's English name, Carlsbad. All of these places were so named because they were the sites of mineral springs or natural sources of mineral water.

Twin towns – Sister cities

Karlovy Vary is twinned with:

Baden-Baden, Germany

Baden-Baden, Germany Bernkastel-Kues, Germany

Bernkastel-Kues, Germany Eilat, Israel

Eilat, Israel Carlsbad, California, United States

Carlsbad, California, United States Cassino, Italy

Cassino, Italy Kusatsu, Japan

Kusatsu, Japan Omsk, Russia

Omsk, Russia Varberg, Sweden

Varberg, Sweden

References

- ↑

- ↑ Vývoj návštěvnosti lázní v letech 2000 - 2011

- ↑ "Karlovy Vary - Urban Monument Zone".

- ↑ "Zdeněk Vališ: 4. březen 1919 v Kadani". Virtually.cz. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ Počet obyvatel Karlovarského kraje

- ↑ Historický lexikon obcí ČR 1869–2005

- ↑ Rozhlas.cz, Počet obyvatel Karlovarského kraje

- ↑ hu:Pulváry Károly

- ↑ http://www.hiddeneurope.co.uk/escape-from-carlsbad

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/40411/Kemal-Ataturk/24780/Military-career

- ↑ Johannes Baier: Goethe und die Thermalquellen von Karlovy Vary (Karlsbad, Tschechische Republik). In: Jahresberichte und Mitteilungen des Oberrheinischen Geologischen Vereins. N. F. Bd. 94, 2012, ISSN 0078-2947, S. 87–103.

- ↑ About Carlsbad, NM retrieved 2012-03-23

- ↑ City of Carlsbad - History of Carlsbad, retrieved 2012-03-23.

Further reading

Published in the 19th century

- "Carlsbad", Southern Germany and Austria (2nd ed.), Coblenz: Karl Baedeker, 1871, OCLC 4090237

- John Merrylees (1886). Carlsbad and its Environs.

Published in the 20th century

- "Carlsbad", Guide through Germany, Austria-Hungary, Switzerland, Italy, France, Belgium, Holland, the United Kingdom, Spain, Portugal, &c (9th ed.), Berlin: J.H. Herz, 1908, OCLC 36795367

- "Carlsbad", The Encyclopaedia Britannica (11th ed.), New York: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1910, OCLC 14782424

- "Carlsbad", Austria-Hungary (11th ed.), Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1911

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Karlovy Vary. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Karlovy Vary. |

- Karlovy Vary regional television channel KTB

- Municipal website (Czech)

- All about Karlovy Vary

- Impressions – slide show

- Sightseeing points (map and videos)

- Pictures & Streetmap from 1725 (?), A. F. Zuerner/Schenck (Amsterdam)

- Pictures & Streetmap from 1733, Homannische Erben (Nuernberg)

- Virtual Tour of Karlovy Vary

- Visitor Information Centre Karlovy Vary

- Karlovy Vary City Card - guide, maps, discounts

_-_flag.gif)