Jurassic

| Jurassic Period 201.3–145 million years ago | |

| |

| Mean atmospheric O 2 content over period duration |

c. 26 vol %[1][2] (130 % of modern level) |

| Mean atmospheric CO 2 content over period duration |

c. 1950 ppm[3][4] (7 times pre-industrial level) |

| Mean surface temperature over period duration | c. 16.5 °C[5][6] (3 °C above modern level) |

| Key events in the Jurassic view • discuss • -205 — – -200 — – -195 — – -190 — – -185 — – -180 — – -175 — – -170 — – -165 — – -160 — – -155 — – -150 — – -145 — – An approximate timescale of key Jurassic events. Vertical axis: millions of years ago. | |

The Jurassic (pronunciation: /dʒuːˈræsɪk/; from Jura Mountains) is a geologic period and system that spans 56.3 million years from the end of the Triassic Period 201.3 million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period 145 Mya.[note 1] The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of the Mesozoic Era, also known as the Age of Reptiles. The start of the period is marked by the major Triassic–Jurassic extinction event. Two other extinction events occurred during the period: the Pliensbachian/Toarcian event in the Early Jurassic, and the Tithonian event at the end; however, neither event ranks among the "Big Five" mass extinctions.

The Jurassic is named after the Jura Mountains within the European Alps, where limestone strata from the period were first identified. By the beginning of the Jurassic, the supercontinent Pangaea had begun rifting into two landmasses, Laurasia to the north and Gondwana to the south. This created more coastlines and shifted the continental climate from dry to humid, and many of the arid deserts of the Triassic were replaced by lush rainforests. On land, the fauna transitioned from the Triassic fauna, dominated by both dinosauromorph and crocodylomorph archosaurs, to one dominated by dinosaurs alone. The first birds also appeared during the Jurassic, having evolved from a branch of theropod dinosaurs. Other major events include the appearance of the earliest lizards, and the evolution of therian mammals, including primitive placentals. Crocodilians made the transition from a terrestrial to an aquatic mode of life. The oceans were inhabited by marine reptiles such as ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs, while pterosaurs were the dominant flying vertebrates.

Etymology

The chronostratigraphic term "Jurassic" is directly linked to the Jura Mountains. Alexander von Humboldt recognized the mainly limestone dominated mountain range of the Jura Mountains as a separate formation that had not been included in the established stratigraphic system defined by Abraham Gottlob Werner, and he named it "Jurakalk" in 1795.[note 2][11][12][13] The name "Jura" is derived from the Celtic root "jor", which was Latinised into "juria", meaning forest (i.e., "Jura" is forest mountains).[11][12][14]

Divisions

The Jurassic period is divided into the Early Jurassic, Middle, and Late Jurassic epochs. The Jurassic System, in stratigraphy, is divided into the Lower Jurassic, Middle, and Upper Jurassic series of rock formations, also known as Lias, Dogger and Malm in Europe.[15] The separation of the term Jurassic into three sections goes back to Leopold von Buch.[13] The faunal stages from youngest to oldest are:

| Upper/Late Jurassic | |

| Tithonian | (152.1 ± 4 – 145 ± 4 Mya) |

| Kimmeridgian | (157.3 ± 4 – 152.1 ± 4 Mya) |

| Oxfordian | (163.5 ± 4 – 157.3 ± 4 Mya) |

| Middle Jurassic | |

| Callovian | (166.1 ± 4 – 163.5 ± 4 Mya) |

| Bathonian | (168.3 ± 3.5 – 166.1 ± 4 Mya) |

| Bajocian | (170.3 ± 3 – 168.3 ± 3.5 Mya) |

| Aalenian | (174.1 ± 2 – 170.3 ± 3 Mya) |

| Lower/Early Jurassic | |

| Toarcian | (182.7 ± 1.5 – 174.1 ± 2 Mya) |

| Pliensbachian | (190.8 ± 1.5 – 182.7 ± 1.5 Mya) |

| Sinemurian | (199.3 ± 1 – 190.8 ± 1.5 Mya) |

| Hettangian | (201.3 ± 0.6 – 199.3 ± 1 Mya) |

Paleogeography and tectonics

During the early Jurassic period, the supercontinent Pangaea broke up into the northern supercontinent Laurasia and the southern supercontinent Gondwana; the Gulf of Mexico opened in the new rift between North America and what is now Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula. The Jurassic North Atlantic Ocean was relatively narrow, while the South Atlantic did not open until the following Cretaceous period, when Gondwana itself rifted apart.[16] The Tethys Sea closed, and the Neotethys basin appeared. Climates were warm, with no evidence of glaciation. As in the Triassic, there was apparently no land over either pole, and no extensive ice caps existed.

The Jurassic geological record is good in western Europe, where extensive marine sequences indicate a time when much of that future landmass was submerged under shallow tropical seas; famous locales include the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site in southern England and the renowned late Jurassic lagerstätten of Holzmaden and Solnhofen in Germany.[17] In contrast, the North American Jurassic record is the poorest of the Mesozoic, with few outcrops at the surface.[18] Though the epicontinental Sundance Sea left marine deposits in parts of the northern plains of the United States and Canada during the late Jurassic, most exposed sediments from this period are continental, such as the alluvial deposits of the Morrison Formation.

The Jurassic was a time of calcite sea geochemistry in which low-magnesium calcite was the primary inorganic marine precipitate of calcium carbonate. Carbonate hardgrounds were thus very common, along with calcitic ooids, calcitic cements, and invertebrate faunas with dominantly calcitic skeletons (Stanley and Hardie, 1998, 1999).

The first of several massive batholiths were emplaced in the northern American cordillera beginning in the mid-Jurassic, marking the Nevadan orogeny.[19] Important Jurassic exposures are also found in Russia, India, South America, Japan, Australasia and the United Kingdom.

In Africa, Early Jurassic strata are distributed in a similar fashion to Late Triassic beds, with more common outcrops in the south and less common fossil beds which are predominated by tracks to the north.[20] As the Jurassic proceeded, larger and more iconic groups of dinosaurs like sauropods and ornithopods proliferated in Africa.[20] Middle Jurassic strata are neither well represented nor well studied in Africa.[20] Late Jurassic strata are also poorly represented apart from the spectacular Tendaguru fauna in Tanzania.[20] The Late Jurassic life of Tendaguru is very similar to that found in western North America's Morrison Formation.[20]

-

Jurassic limestones and marls (the Matmor Formation) in southern Israel.

-

The late Jurassic Morrison Formation in Colorado is one of the most fertile sources of dinosaur fossils in North America.

-

Gigandipus, a dinosaur footprint in the Lower Jurassic Moenave Formation at the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm, southwestern Utah.

-

The Permian through Jurassic stratigraphy of the Colorado Plateau area of southeastern Utah.

Fauna

Aquatic and marine

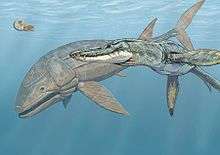

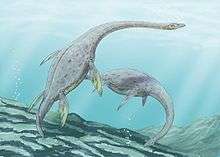

During the Jurassic period, the primary vertebrates living in the sea were fish and marine reptiles. The latter include ichthyosaurs, which were at the peak of their diversity, plesiosaurs, pliosaurs, and marine crocodiles of the families Teleosauridae and Metriorhynchidae.[21] Numerous turtles could be found in lakes and rivers.[22][23]

In the invertebrate world, several new groups appeared, including rudists (a reef-forming variety of bivalves) and belemnites. Calcareous sabellids (Glomerula) appeared in the Early Jurassic.[24][25] The Jurassic also had diverse encrusting and boring (sclerobiont) communities, and it saw a significant rise in the bioerosion of carbonate shells and hardgrounds. Especially common is the ichnogenus (trace fossil) Gastrochaenolites.[26]

During the Jurassic period, about four or five of the twelve clades of planktonic organisms that exist in the fossil record either experienced a massive evolutionary radiation or appeared for the first time.[15]

-

A Pliosaurus (right) harassing a Leedsichthys in a Jurassic sea.

-

Ichthyosaurus from lower (early) Jurassic slates in southern Germany featured a dolphin-like body shape.

-

Plesiosaurs like Muraenosaurus roamed Jurassic oceans.

Terrestrial

On land, various archosaurian reptiles remained dominant. The Jurassic was a golden age for the large herbivorous dinosaurs known as the sauropods—Camarasaurus, Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, Brachiosaurus, and many others—that roamed the land late in the period; their foraging grounds were either the prairies of ferns, palm-like cycads and bennettitales, or the higher coniferous growth, according to their adaptations. The smaller Ornithischian herbivor dinosaurs, like stegosaurs and small ornithopods were less predominant, but played important roles. They were preyed upon by large theropods, such as Ceratosaurus, Megalosaurus, Torvosaurus and Allosaurus. All these belong to the 'lizard hipped' or saurischian branch of the dinosaurs.[27] During the Late Jurassic, the first avialans, like Archaeopteryx, evolved from small coelurosaurian dinosaurs. In the air, pterosaurs were common; they ruled the skies, filling many ecological roles now taken by birds,[28] and may have already produced some of the largest flying animals of all time.[29][30] Within the undergrowth were various types of early mammals, as well as tritylodonts, lizard-like sphenodonts, and early lissamphibians. The rest of the Lissamphibia evolved in this period, introducing the first salamanders and caecilians.[31]

-

Diplodocus, reaching lengths over 30 m, was a common sauropod during the late Jurassic.

-

Allosaurus was one of the largest land predators during the Jurassic.

-

Stegosaurus is one of the most recognizable genera of dinosaurs and lived during the mid to late Jurassic.

-

Archaeopteryx, a primitive bird-like reptiles, appeared in the Late Jurassic.

Flora

The arid, continental conditions characteristic of the Triassic steadily eased during the Jurassic period, especially at higher latitudes; the warm, humid climate allowed lush jungles to cover much of the landscape.[32] Gymnosperms were relatively diverse during the Jurassic period.[15] The Conifers in particular dominated the flora, as during the Triassic; they were the most diverse group and constituted the majority of large trees.

Extant conifer families that flourished during the Jurassic included the Araucariaceae, Cephalotaxaceae, Pinaceae, Podocarpaceae, Taxaceae and Taxodiaceae.[33] The extinct Mesozoic conifer family Cheirolepidiaceae dominated low latitude vegetation, as did the shrubby Bennettitales.[34] Cycads, similar to palm trees, were also common, as were ginkgos and Dicksoniaceous tree ferns in the forest.[15] Smaller ferns were probably the dominant undergrowth. Caytoniaceous seed ferns were another group of important plants during this time and are thought to have been shrub to small-tree sized.[35] Ginkgo plants were particularly common in the mid- to high northern latitudes.[15] In the Southern Hemisphere, podocarps were especially successful, while Ginkgos and Czekanowskiales were rare.[32][34]

In the oceans, modern coralline algae appeared for the first time.[15] However, they were a part of another major extinction that happened within the next major time period.

See also

Explanatory notes

- ↑ A 140 Ma age for the Jurassic-Cretaceous instead of the usually accepted 145 Ma was proposed in 2014 based on a stratigraphic study of Vaca Muerta Formation in Neuquén Basin, Argentina.[7] Víctor Ramos, one of the authors of the study proposing the 140 Ma boundary age, sees the study as a "first step" toward formally changing the age in the International Union of Geological Sciences.[8]

- ↑ Humboldt names the Jura limestone ("Jurakalkstein") deposit[9] " … die ausgebreitete Formation, welche zwischen dem alten Gips und neueren Sandstein liegt, und welchen ich vorläufig mit dem Nahmen Jura-Kalkstein bezeichne." ( … the widespread formation which lies between the old gypsum and the more recent sandstone and which I provisionally designate with the name "Jura limestone".)

He explains that he coined the name during a tour of the region in 1795[10] "Ich hatte mich auf einer geognostischen Reise, die ich 1795 durch das südliche Franken, die westliche Schweiz and Ober-Italien machte, davon überzeugt, daß der Jura-Kalkstein, welchen Werner zu seinem Muschelkalk rechnete, eine eigne Formation bildete. In meiner Schrift über die unterirdischen Gasarten, welche mein Bruder Wilhelm von Humboldt 1799 während meines Aufenthalts in Südamerika herausgab, wird der Formation, die ich vorläufig mit dem Namen Jura-Kalkstein bezeichnete, zuerst (S. 39) gedacht." (On a geological tour that I made in 1795 through southern France, western Switzerland and upper Italy, I convinced myself that the Jura limestone, which Werner included in his shell limestone, constituted a separate formation. In my paper about subterranean types of gases, which my brother Wilhelm von Humboldt published in 1799 during my stay in South America, the formation, which I provisionally designated with the name "Jura limestone", is first conceived (p. 39).)

Notes

- ↑ Image:Sauerstoffgehalt-1000mj.svg

- ↑ Image:OxygenLevelsThroughEarthHistory.png

- ↑ Image:Phanerozoic Carbon Dioxide.png

- ↑ Image:CO2LevelsThroughEarthHistory.png

- ↑ Image:All palaeotemps.png

- ↑ Image:TemperatureLevelsOverEarthHistory.png

- ↑ Vennari, Verónica V.; Lescano, Marina; Naipauer, Maximiliano; Aguirre-Urreta, Beatriz; Concheyro, Andrea; Schaltegger, Urs; Armstrong, Richard; Pimentel, Marcio; Ramos, Victor A. (2014). "New constraints on the Jurassic–Cretaceous boundary in the High Andes using high-precision U–Pb data". Gondwana Research. 26: 374–385. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ↑ Jaramillo, Jessica. "Entrevista al Dr. Víctor Alberto Ramos, Premio México Ciencia y Tecnología 2013" (in Spanish).

Si logramos publicar esos nuevos resultados, sería el primer paso para cambiar formalmente la edad del Jurásico-Cretácico. A partir de ahí, la Unión Internacional de la Ciencias Geológicas y la Comisión Internacional de Estratigrafía certificaría o no, depende de los resultados, ese cambio.

- ↑ Alexander von Humboldt, Ueber die unterirdischen Gasarten und die Mittel, ihren Nachteil zu vermindern, ein Beitrag zur Physik der praktischen Bergbaukunde [On the types of subterranean gases and means of minimizing their harm, a contribution to the physics of practical mining] (Braunschweig, (Germany): Vieweg, 1799), p. 39. p. 39

- ↑ Alexander von Humboldt, Kosmos, volume 4 (Stuttgart, (Germany): Cotta, 1858), p. 632. p. 632.

- 1 2 Hölder, H. 1964. Jura — Handbuch der stratigraphischen Geologie, IV. Enke-Verlag, 603 pp., 158 figs, 43 tabs; Stuttgart

- 1 2 Arkell, W.J. 1956. Jurassic Geology of the World. Oliver & Boyd, 806 pp.; Edinburgh und London.

- 1 2 Pieńkowski, G.; Schudack, M.E.; Bosák, P.; Enay, R.; Feldman-Olszewska, A.; Golonka, J.; Gutowski, J.; Herngreen, G.F.W.; Jordan, P.; Krobicki, M.; Lathuiliere, B.; Leinfelder, R.R.; Michalík, J.; Mönnig, E.; Noe-Nygaard, N.; Pálfy, J.; Pint, A.; Rasser, M.W.; Reisdorf, A.G.; Schmid, D.U.; Schweigert, G.; Surlyk, F.; Wetzel, A. & Theo E. Wong, T.E. 2008. Jurassic. In: McCann, T. (ed.): The Geology of Central Europe. Volume 2: Mesozoic and Cenozoic, Geological Society, pp.: 823-922; London.

- ↑ Rollier, L. 1903. Das Schweizerische Juragebirge. Sonderabdruck aus dem Geographischen Lexikon der Schweiz, Verlag von Gebr. Attinger, 39 pp; Neuenburg

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kazlev, M. Alan (2002) Palaeos website Accessed July. 22, 2008

- ↑ Late Jurassic

- ↑ Jurassic Period

- ↑ map

- ↑ Monroe and Wicander, 607.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jacobs, Louis, L. (1997). "African Dinosaurs". Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Edited by Phillip J. Currie and Kevin Padian. Academic Press. p. 2-4.

- ↑ Motani, R. (2000), Rulers of the Jurassic Seas, Scientific American vol.283, no. 6

- ↑ Wings, Oliver; Rabi, Márton; Schneider, Jörg W.; Schwermann, Leonie; Sun, Ge; Zhou, Chang-Fu; Joyce, Walter G. (2012), "An enormous Jurassic turtle bone bed from the Turpan Basin of Xinjiang, China", Naturwissenschaften: The Science of Nature, 114, Bibcode:2012NW.....99..925W, doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0974-5

- ↑ Gannon, Megan (October 31, 2012), "Jurassic turtle graveyard found in China", Livescience.com

- ↑ Vinn, O.; Mutvei, H. (2009). "Calcareous tubeworms of the Phanerozoic" (PDF). Estonian Journal of Earth Sciences. 58 (4): 286–296. doi:10.3176/earth.2009.4.07. Retrieved 2012-09-16.

- ↑ Vinn, O.; ten Hove, H.A.; Mutvei, H. (2008). "On the tube ultrastructure and origin of calcification in sabellids (Annelida, Polychaeta)". Palaeontology. 51: 295–301. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00763.x. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ↑ Taylor, P. D.; Wilson, M. A. (2003). "Palaeoecology and evolution of marine hard substrate communities". Earth-Science Reviews. 62 (1–2): 1–103. Bibcode:2003ESRv...62....1T. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(02)00131-9.

- ↑ Haines, Tim (2000). Walking with Dinosaurs: A Natural History. New York: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 0-7894-5187-5.

- ↑ Feduccia, A. (1996). The Origin and Evolution of Birds. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06460-8.

- ↑ Witton, Mark P.; Martill, David M.; Loveridge, Robert F. (2010). "Clipping the Wings of Giant Pterosaurs: Comments on Wingspan Estimations and Diversity". Acta Geoscientica Sinica. 31 (Supp 1): 79–81.

- ↑ Why the giant azhdarchid Arambourgiania philadelphiae needs a fanclub

- ↑ Carroll, R. L. (1988). Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. New York: WH Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-1822-7.

- 1 2 Haines, 2000.

- ↑ Behrensmeyer et al., 1992, 349.

- 1 2 Behrensmeyer et al., 1992, 352

- ↑ Behrensmeyer et al., 1992, 353

References

- Behrensmeyer, Damuth, J.D., DiMichele, W.A., Potts, R., Sues, H.D. & Wing, S.L. (eds.) (1992), Terrestrial Ecosystems through Time: the Evolutionary Paleoecology of Terrestrial Plants and Animals, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, ISBN 0-226-04154-9 (cloth), ISBN 0-226-04155-7 (paper).

- Haines, Tim (2000) Walking with Dinosaurs: A Natural History, New York: Dorling Kindersley Publishing, Inc., p. 65. ISBN 0-563-38449-2.

- Kazlev, M. Alan (2002) Palaeos website Accessed Jan. 8, 2006.

- Mader, Sylvia (2004) Biology, eighth edition.

- Monroe, James S., and Reed Wicander. (1997) The Changing Earth: Exploring Geology and Evolution, 2nd ed. Belmont: West Publishing Company, 1997. ISBN 0-314-09577-2.

- Ogg, Jim; June, 2004, Overview of Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points (GSSP's), International Commission on Stratigraphy, pp. 17

- Stanley, S.M. and Hardie, L.A. (1998). "Secular oscillations in the carbonate mineralogy of reef-building and sediment-producing organisms driven by tectonically forced shifts in seawater chemistry". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 144: 3–19.

- Stanley, S.M. and Hardie, L.A. (1999). "Hypercalcification; paleontology links plate tectonics and geochemistry to sedimentology". GSA Today 9: 1–7.

- Taylor, P.D. and Wilson, M.A., (2003). Palaeoecology and evolution of marine hard substrate communities. Earth-Science Reviews 62: 1–103. .

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jurassic. |

| Look up jurassic in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Examples of Jurassic Fossils

- Palaeos.com

- Jurassic fossils in Harbury, Warwickshire

- Jurassic Microfossils: 65+ images of Foraminifera

| Jurassic Period | ||

|---|---|---|

| Lower/Early Jurassic | Middle Jurassic | Upper/Late Jurassic |

| Hettangian | Sinemurian Pliensbachian | Toarcian |

Aalenian | Bajocian Bathonian | Callovian |

Oxfordian | Kimmeridgian Tithonian |

| Preceded by Proterozoic Eon | Phanerozoic Eon | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paleozoic Era | Mesozoic Era | Cenozoic Era | ||||||||||

| Cambrian | Ordovician | Silurian | Devonian | Carboniferous | Permian | Triassic | Jurassic | Cretaceous | Paleogene | Neogene | 4ry | |