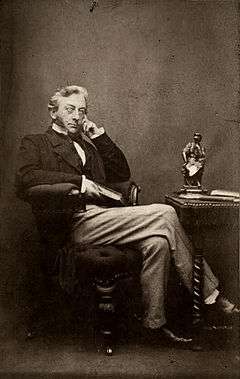

John Walpole Willis

John Walpole Willis (4 January 1793 – 10 September 1877) was an English-born judge, and a judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales.

Early life

The second son of Captain William Willis (of the 13th Light Dragoons) and his wife Mary Hamilton Smyth, Willis was born at Holyhead, Anglesey, where his father was stationed. He was a descendant of the Willises of Suffolk and Cambridgeshire- from whom descended the Willys baronets of Fen Ditton- through his grandfather, Joseph Willis of Wakefield, Yorkshire, where the family had been settled since the seventeenth century. Willis was educated at Rugby, Charterhouse (whence he was expelled) and Trinity Hall, Cambridge,[1][2] where he took an M.A.[3] He was called to the English bar and practised as a chancery barrister. In 1820-1 he published his Pleadings in Equity, and in 1827 A Practical Treatise on the Duties and Responsibilities of Trustees.[4] In 1823, the Earl of Strathmore applied to Willis for legal advice; while a frequent guest in the Earl's household, Willis met his daughter, Lady Mary Isabella. They married the following year, and settled with Willis's widowed mother and his sister at Hendon. Their son, Robert Bruce Willis, was born in 1826.

Upper Canada and British Guiana

In 1827, with his father-in-law's endorsement, Willis was appointed a puisne judge of the Court of King's bench in Upper Canada,with the expectation being that a Court of Chancery would be established shortly after at which he would be the judge.[5] Willis and his family arrived in Canada on 17 September. Although at first he and his wife were welcomed into the social and legal life of the colony, within a few months Willis fell foul of the attorney-general, John Beverley Robinson, a very experienced official, and took the most unusual course of stating in court that Robinson had neglected his duty and that he would feel it necessary "to make a representation on the subject to his majesty's government". Willis had a low opinion of Robinson, having previously observed "that any proposition that did not originate with himself was not generally attended with his approbation".[6] Willis allied himself with a group of lawyers who were chief opposition spokesmen: John Rolph, William Warren Baldwin and his son Robert, and Marshall Spring Bidwell. Another friend was the novelist- at that time Secretary of the Canada Company- John Galt.[7] Willis also took a strong stand on the question of the legality of the court as then constituted, and this led in June 1828 to his being removed from his position by the lieutenant-governor, Sir Peregrine Maitland, with whose wife, Lady Sarah, Willis's wife had had a disagreement regarding precedence.[4][6]

Willis returned to England in July with his mother (during which time they also stayed at Tyrella House, Dundrum Bay, County Down, the home of Rev. George Hamilton, a cousin of his mother),[8] leaving his sister, wife and son behind in the care of his friends. This separation led to the dissolution of his marriage; his wife, in May 1829, leaving her son with a maid and absconding with an infantry lieutenant.[6] The question was referred to the privy council which ruled against Willis. His conduct was treated as an error of judgment and he was given another appointment as a judge in Demerara, British Guiana, appointed Vice-President of the Court of Civil and Criminal Justice.[4][5] He served as first puisne judge, i.e. second in rank after the Chief Justice, Charles Wray.[9][10] At first, Willis seemed well-suited to Guiana; he avoided becoming embroiled in local politics, and enjoyed close and cordial relations with a number of the colony's influential people.[11] However, in 1835 he was passed over for promotion to Chief Justice there in favour of Jeffery Hart Bent, formerly the Chief Justice of St Lucia, and a similarly divisive figure,[12] despite Willis having served as first puisne judge under the previous Chief Justice, Charles Wray, and having been acting chief justice on Wray's retirement; within three months, embittered by this and experiencing chronic liver trouble (likely malarial, or related to amoebic dysentery),[13] he returned to England on sick leave. During this period, he married Ann Susanna Kent Bund, daughter and heir of Col. Thomas Henry Bund, of Wick House, Worcestershire. When Willis was due to return, he was, at the insistence of the Governor of British Guiana, instead persuaded by the Colonial Office to take a posting in Sydney as a judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales.

New South Wales

On 3 November 1837 he arrived in Sydney with his new wife. Initially Willis was on good terms with Sir James Dowling (who a few months later became chief justice), but in 1839 differences arose, and on one occasion Willis in open court made observations which were taken as a reflection on the chief justice. He also brought forward the question whether the chief justice had forfeited his office by acting as judge of the admiralty court. Matters came to such a pass that in March 1840 the governor, Sir George Gipps, arranged that Willis should be appointed resident judge at Melbourne. Arriving in Melbourne with 43 tonnes of luggage,[5] he soon came in conflict with the press, the legal fraternity, and members of the public. In October 1842 Gipps stated in a dispatch that:

| “ | differences have again broken out between Mr J. Walpole Willis . . . a and the judges of the supreme court of Sydney ... for many months the town of Melbourne has been kept in a state of continued excitement by the proceedings of Mr Justice Willis and the extraordinary nature of the harangues, which he is in the habit of delivering from the bench. | ” |

In February 1843 Gipps recommended to Lord Stanley that Willis should be removed from his position. Willis left Melbourne for London later in February and appealed to the English government. In August 1846 the privy council reversed the order for his dismissal on technical grounds, and he was awarded the arrears of his salary to that date. Willis then offered his resignation, but this was not accepted and his commission was revoked. This course was taken because otherwise it might not have been understood that the order was reversed not as being "unjust in itself, but only as having been made in an improper manner"[14] Willis was never given any other position.[4]

Late life

In 1850 Willis published a volume On the Government of the British Colonies (noted in The Athenaeum magazine as 'not unworthy of the attention of those who are seeking... a way out of our present colonial difficulties'),[15] and afterwards lived in retirement at Wick Episcopi, Worcestershire, serving as a Deputy Lieutenant and Justice of the Peace for the county.[1] He died on 10 September 1877, survived by the son of his first marriage, and by a son John William Willis-Bund and two daughters by the second marriage.[4]

Character

Despite his considerable ability, Willis was noted to have a naturally rather difficult temperament, which was not improved by his clashes with colleagues over what he perceived as their lax moral standards.[6] The novelist Rolf Boldrewood, Willis's neighbour while posted in Sydney, described his 'genial and gracious' personality while shooting, which when in court became "impatience of contradiction... acerbity of manner, and... infirmity of temper" "painful to witness and dangerous to encounter".[16] The Melbourne journalist and author Garryowen recorded: "Such was his irascibility and so often was the Court the arena of unseemly squabbles that people who had no business there attended to see 'the fun', for, as there was no theatre in town, Judge Willis was reckoned to be 'as good as a play'". Nonetheless, he was known for his brilliance and wit,[17] as well as "a humaneness that was unfashionable, even unsavoury, for the times", as shown by his provision- at his own expense- of roast beef and plum pudding to all the prisoners in Melbourne jail on New Year's Day 1842.[18] Despite a "haughty and imperious" [19] manner, Willis was nonetheless popular with the public, receiving strong support from certain quarters. He was regarded as "a martyr to his upright and liberal principles"; his amoval "tended greatly to embitter public opinion, and was unquestionably a strong factor in producing the discontent which ultimately found expression in open rebellion".[6] Henry James Morgan, author of 'Sketches of celebrated Canadians and persons connected with Canada' considered that Willis "received such base and unprincipled treatment at [the hands of those in power] for no reason but because he did his duty well, was an English lawyer of great legal ability and knowledge; and also a gentleman of much goodness and amiability of character... he displayed great judgement, and an accurate acquaintance with his official duties, and was considered an honour to the bench (heretofore not in very high repute) not only for his talents and merits as a lawyer, but for his very excellent disposition, and for the manner in which he maintained the dignity and impartiality of the court... such a man was not in favour with the omnipotent power that ruled the upper province; and a strong dislike was taken against him."[20] George Wright, in "Wattle blossoms: some of the grave and gay reminiscences of an old colonist" characterised Willis in his time in Australia as "one of those noble souled men who feared nothing so much as an accusing conscience, and therefore dared on all occasions to speak truth for truth's sake".[21] John Charles Dent, in 'The Canadian Portrait Gallery volume I', considered Willis "a gentleman of spotless character, kind and amiable manners, and wide and various learning. He was beyond comparison the ablest jurist who, up to that point, had sat on the judicial bench".[22]

Notes

- 1 2 "Willis, John Walpole (WLS820JW)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ John V. Barry (1967). "Willis, John Walpole (1793 - 1877)". Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 2. MUP. pp. 602–604. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ↑ A Synopsis of the Members of the English Bar, James Whishaw, Stevens and Sons, 1835, pg 156

- 1 2 3 4 5 Serle, Percival (1949). "Willis, John Walpole". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- 1 2 3 'A new miscellany-at-law: yet another diversion for lawyers and others', Sir Robert Edgar Megarry, Bryan A. Garner, 2005

- 1 2 3 4 5 'The story of the Upper Canadian Rebellion', John Charles Dent, 1885

- ↑ Alan Wilson. "Willis, John Walpole". Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Volume X 1871-1880. Retrieved 2013-01-31.

- ↑ Judge John Walpole Willis and Lady Mary Willis: The Canadian experience & its aftermath, J. C. Foweraker, 2009

- ↑ https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=edVbAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA185&lpg=PA185&dq=first+puisne+judge&source=bl&ots=SCQAs5p8Px&sig=ppjdaV72Uqnw51ipG8xEgxv-u8U&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwizu4zKwOTKAhWEPxoKHfEaAwgQ6AEIXDAK#v=onepage&q=first%20puisne%20judge&f=false

- ↑ https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=ZxA5AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA841&lpg=PA841&dq=first+puisne+judge&source=bl&ots=tw7_ck-aZW&sig=ytP3J9WiwvfiBT2QqU4vVFEcrbY&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwizu4zKwOTKAhWEPxoKHfEaAwgQ6AEIXjAL#v=onepage&q=first%20puisne%20judge&f=false

- ↑ Dewigged, Bothered, and Bewildered: British Colonial Judges on Trial, 1800-1900, John McLaren, University of Toronto Press, 2011, pg 171

- ↑ Dewigged, Bothered, and Bewildered: British Colonial Judges on Trial, 1800-1900, John McLaren, University of Toronto Press, 2011, pg 171

- ↑ Dewigged, Bothered, and Bewildered: British Colonial Judges on Trial, 1800-1900, John McLaren, University of Toronto Press, 2011, pg 171

- ↑ Historical Records of Australia, ser. I, vol. XXV, p. 208.

- ↑ The Athenaeum, no 1198, pg 1069

- ↑ 'Redmond Barry: an Anglo-Irish Australian', Ann Galbally, 1995

- ↑ 'Bearbrass: Imagining early Melbourne', Robyn Annear, 2005

- ↑ 'Bearbrass: Imagining early Melbourne', Robyn Annear, 2005

- ↑ 'The Canada Company and the Huron Tract, 1826-1853', Robert Charles Lee, 2004

- ↑ 'Sketches of celebrated Canadians and persons connected with Canada', Henry James Morgan, 1862

- ↑ 'Wattle blossoms: some of the grave and gay reminiscences of an old colonist', George Wright, 1857

- ↑ 'The Canadian Portrait Gallery volume I', John Charles Dent, 1841

References

Additional resources listed by the Australian Dictionary of Biography:

- Historical Records of Australia, series 1, vols 19-22

- E. F. Moore, Reports, vol 5, p 379

- T. McCombie, The History of the Colony of Victoria (Melb, 1858)

- J. L. Forde, The Story of the Bar of Victoria (Melb, no date)

- R. Therry, Reminiscences of Thirty Years' Residence in New South Wales and Victoria (Lond, 1863)

- Garryowen (E. Finn), Chronicles of Early Melbourne, vols 1-2 (Melb, 1888)

- G. B. Vasey, 'John Walpole Willis', Victorian Historical Magazine, 1 (1911).

- H. F. Behan, 'Mr Justice J. W. Willis - With particular reference to his period as First Resident Judge in Port Phillip 1841-1843' (Glen Iris, Victoria, Australia, 1979).

- John McLaren, 'Dewigged, Bothered and Bewildered - British Colonial Judges on Trial, 1800-1900' (University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 2011).

External links

"John Walpole Willis". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. 1979–2016.