Jean-Étienne Liotard

Jean-Étienne Liotard (22 December 1702 – 12 June 1789) was a Swiss-French painter, art connoisseur and dealer.

Life

Liotard was born at Geneva. His father was a jeweller who fled to Switzerland after 1685. Jean-Étienne Liotard began his studies under Professors Gardelle and Petitot, whose enamels and miniatures he copied with considerable skill.

He went to Paris in 1725, studying under Jean-Baptiste Massé and François Lemoyne, on whose recommendation he was taken to Naples by the vicomte de Puysieux, Louis Philogène Brulart, Marquis de Puysieulx and Comte de Sillery. In 1735 he was in Rome, painting the portraits of Pope Clement XII and several cardinals. Three years later he accompanied Lord Duncannon to Constantinople.

Jean-Étienne Liotard visited Istanbul and painted numerous pastels of Turkish domestic scenes; he also continued to wear Turkish dress for much of the time when back in Europe. Using modern dress was considered unheroic and inelegant in history painting using Middle Eastern settings, with Europeans wearing local costume, as travellers were advised to do.

Many travellers had themselves painted in exotic Eastern dress on their return, including Lord Byron, as did many who had never left Europe, including Madame de Pompadour.[1] Byron's poetry was highly influential in introducing Europe to the heady cocktail of Romanticism in exotic Oriental settings which was later to dominate 19th century Oriental art.

His eccentric adoption of oriental costume secured him the nickname of the Turkish painter.

He went to Vienna in 1742 to paint the portraits of the Imperial family. In 1745 he sold La belle chocolatière to Francesco Algarotti.

Still under distinguished patronage he returned to Paris. In 1753 he visited England, where he painted Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, the Princess of Wales. He went to Holland in 1756, where, in the following year, he married Marie Fargues. She also came from a Hugenot family, and wanted him to shave off his beard.

In 1762 he painted portraits in Vienna; in 1770 in Paris. Another visit to England followed in 1772, and in the next two years his name figures among the Royal Academy exhibitors. He returned to his native town in 1776. In 1781 Liotard published his Traité des principes et des règles de la peinture. In his last days he painted still lifes and landscapes. He died at Geneva in 1789.

Works

Liotard was an artist of great versatility. Best known for his graceful and delicate pastel drawings,[2] of which La Liseuse, The Chocolate Girl, and La Belle Lyonnaise at the Dresden Gallery and Maria Frederike van Reede-Athlone at Seven at the J. Paul Getty Museum are delightful examples, he also achieved distinction for his enamels, copperplate engravings, and glass painting. Additionally, he wrote a Treatise on the Art of Painting and was an expert collector of paintings by the old masters.

Many of the masterpieces he had acquired were sold by him at high prices on his second visit to England. The museums of Amsterdam, Bern, and Geneva are particularly rich in examples of his paintings and pastel drawings. A picture of a Turk seated is at the Victoria and Albert Museum, while the British Museum owns two of his drawings.

The Louvre has, besides twenty-two drawings, a portrait of Lieutenant General Hrault as well as an oil painting of an English merchant and a friend dressed in costumes and entitled Monsieur Levett and Mademoiselle Helene Glavany in Turkish Costumes. A portrait of the artist is to be found at the Sala di pittori, in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. While his son also married a Dutch girl, the Rijksmuseum inherited an important collection of his drawings and paintings.

One outstanding feature of Liotard's paintings is the prevalence of smiling subjects. Generally, portrait subjects of the time adopted a more serious tone. This levity was a reflection of the Enlightenment-era philosophies that inspired Liotard.[2] Also indicative of the era, Liotard created works celebrating science, like the painting of woman paying homage to the doctor that saved her. [2]

- Selected works

Marie Charlotte Boissier

Marie Charlotte Boissier Jeanne-Elisabeth de Sellon

Jeanne-Elisabeth de Sellon Richard Pococke (1704-1765)

Richard Pococke (1704-1765) Marie Josèphe von Sachsen

Marie Josèphe von Sachsen- Ami-Jean de la Rive

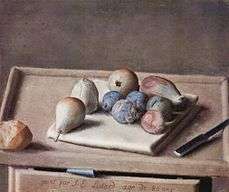

Stilllife with figs

Stilllife with figs Portrait of Mademoiselle Jacquet

Portrait of Mademoiselle Jacquet Portrait of a Young Woman

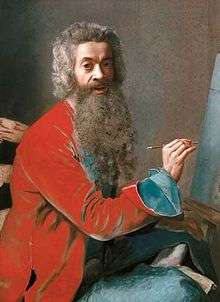

Portrait of a Young Woman Self-portrait, 1773

Self-portrait, 1773 Portrait of Monsieur Boère, merchand from Genua

Portrait of Monsieur Boère, merchand from Genua Queen Maria Theresia (1717-1780)

Queen Maria Theresia (1717-1780) The Chocolate Girl

The Chocolate Girl The first cup

The first cup Maria Frederike van Reede-Athlone

Maria Frederike van Reede-Athlone Portrait of François Tronchin

Portrait of François Tronchin Marie Adalaide

Marie Adalaide.jpg) Portrait of a Turkish grand vizier, probably Hekimoğlu Ali Pasha

Portrait of a Turkish grand vizier, probably Hekimoğlu Ali Pasha Portrait of Frederick, Prince of Wales (1707-1751)

Portrait of Frederick, Prince of Wales (1707-1751) Count Francesco Algarotti, 1745

Count Francesco Algarotti, 1745

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jean-Étienne Liotard. |

External links

- Short biography

- 74 works by Liotard at the Musées d'Art et d'Histoire, Geneva

- Some paintings of Liotard in the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum

- Liotard on a Danish website

- Liotard in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of pastellists before 1800, online edition

- Liotard paintings at The J. Paul Getty Museum

References

- ↑ Christine Riding, Travellers and Sitters: The Orientalist Portrait, in Tromans, 48-75

- 1 2 3 Jonathan Jones, Jean-Etienne Liotard review – a joyous time machine back to the Enlightenment, The Guardian, 20 October 2015.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.