Jaynes–Cummings model

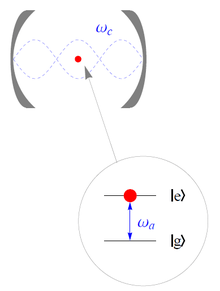

The Jaynes–Cummings model (JCM) is a theoretical model in quantum optics. It describes the system of a two-level atom interacting with a quantized mode of an optical cavity, with or without the presence of light (in the form of a bath of electromagnetic radiation that can cause spontaneous emission and absorption). The JCM is of great interest in atomic physics, quantum optics, and solid-state quantum information circuits, both experimentally and theoretically.

History

This model was originally proposed in 1963 by Edwin Jaynes and Fred Cummings in order to study the relationship between the quantum theory of radiation and the semi-classical theory in describing the phenomenon of spontaneous emission.[1]

In the earlier semi-classical theory of field-atom interaction, only the atom is quantized and the field is treated as a definite function of time rather than as an operator. The semi-classical theory can explain many phenomena that are observed in modern optics, for example the existence of Rabi cycles in atomic excitation probabilities for radiation fields with sharply defined energy (narrow bandwidth). The JCM serves to find out how quantization of the radiation field affects the predictions for the evolution of the state of a two-level system in comparison with semi-classical theory of light-atom interaction. It was later discovered that the revival of the atomic population inversion after its collapse is a direct consequence of discreteness of field states (photons).[2][3] This is a pure quantum effect that can be described by the JCM but not with the semi-classical theory.

Twenty four years later, in 1987, a beautiful demonstration of quantum collapse and revival was observed in a one-atom maser by Rempe, Walther, and Klein.[4] Before that time, research groups were unable to build experimental setups capable of enhancing the coupling of an atom with a single field mode, simultaneously suppressing other modes. Experimentally, the quality factor of the cavity must be high enough to consider the dynamics of the system as equivalent to the dynamics of a single mode field. With the advent of one-atom masers it was possible to study the interaction of a single atom (usually a Rydberg atom) with a single resonant mode of the electromagnetic field in a cavity from an experimental point of view,[5][6] and study different aspects of the JCM.

To observe strong atom-field coupling in visible light frequencies hour-glass-type optical modes can be helpful because of their large mode volume that eventually coincides with a strong field inside the cavity.[7] A quantum dot inside a photonic crystal nano-cavity is also a promising system for observing collapse and revival of Rabi cycles in the visible light frequencies.[8]

In order to more precisely describe the interaction between an atom and a laser field, the model is generalized in different ways. Some of the generalizations are applying initial conditions,[9] consideration of dissipation and damping in the model,[9][10] [11] consideration of multilevel atoms and multiple atoms, [12] [13] and multi-mode description of the field.[14]

It was also discovered that during the quiescent intervals of collapsed Rabi oscillations the atom and field exist in a macroscopic superposition state (a Schrödinger cat). This discovery offers the opportunity to use the JCM to elucidate the basic properties of quantum correlation (entanglement).[15] In another work the JCM is employed to model transfer of quantum information.[16]

A more recent reference reviewing the Physics of the Jaynes–Cummings model is Journal of Physics B, 2013, vol. 46, #22, containing numerous relevant articles, including two interesting editorials, one by Cummings.

The generalization of the Jaynes–Cummings model to atoms with more than two levels (equivalent to spins higher than 1/2) is known as the Dicke model or the Tavis-Cummings model.

Formulation

The Hamiltonian that describes the full system,

consists of the free field Hamiltonian, the atomic excitation Hamiltonian, and the Jaynes–Cummings interaction Hamiltonian:

Here, for convenience, the vacuum field energy is set to .

For deriving the JCM interaction Hamiltonian the quantized radiation field is taken to consist of a single bosonic mode with the field operator , where the operators and are the bosonic creation and annihilation operators and is the angular frequency of the mode. On the other hand, the two-level atom is equivalent to a spin-half whose state can be described using a three-dimensional Bloch vector. (It should be understood that "two-level atom" here is not an actual atom with spin, but rather a generic two-level quantum system whose Hilbert space is isomorphic to a spin-half.) The atom is coupled to the field through its polarization operator . The operators and are the raising and lowering operators of the atom. The operator is the atomic inversion operator, and is the atomic transition frequency.

JCM Hamiltonian

Moving from the Schrödinger picture into the interaction picture (a.k.a. rotating frame) defined by the choice , we obtain

This Hamiltonian contains both quickly and slowly oscillating components. To get a solvable model, when the quickly oscillating "counter-rotating" terms can be ignored. This is referred to as the rotating wave approximation. Transforming back into the Schrödinger picture the JCM Hamiltonian is thus written as

Eigenstates

It is possible, and often very helpful, to write the Hamiltonian of the full system as a sum of two commuting parts:

where

with called the detuning (frequency) between the field and the two-level system.

The eigenstates of , being of tensor product form, are easily solved and denoted by , where denotes the number of radiation quanta in the mode.

As the states and are degenerate with respect to for all , it is enough to diagonalize in the subspaces . The matrix elements of in this subspace, read

For a given , the energy eigenvalues of are

where is the Rabi frequency for the specific detuning parameter. The eigenstates associated with the energy eigenvalues are given by

where the angle is defined through

Schrödinger picture dynamics

It is now possible to obtain the dynamics of a general state by expanding it on to the noted eigenstates. We consider a superposition of number states as the initial state for the field, , and assume an atom in the excited state is injected into the field. The initial state of the system is

Since the are stationary states of the field-atom system, then the state vector for times is just given by

The Rabi oscillations can readily be seen in the sin and cos functions in the state vector. Different periods occur for different number states of photons. What is observed in experiment is the sum of many periodic functions that can be very widely oscillating and destructively sum to zero at some moment of time, but will be non-zero again at later moments. Finiteness of this moment results just from discreteness of the periodicity arguments. If the field amplitude were continuous, the revival would have never happened at finite time.

Heisenberg picture dynamics

It is possible in the Heisenberg notation to directly determine the unitary evolution operator from the Hamiltonian:[17]

where the operator is defined as

The unitarity of is guaranteed by the identities

and their Hermitian conjugates.

By the unitary evolution operator one can calculate the time evolution of the state of the system described by its density matrix , and from there the expectation value of any observable, given the initial state:

The initial state of the system is denoted by and is an operator denoting the observable.

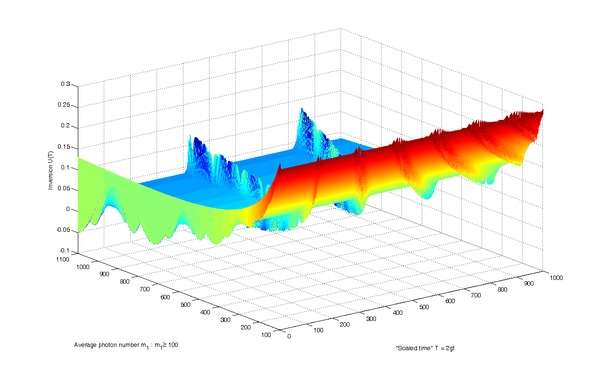

Collapses and revivals of quantum oscillations

The plot of quantum oscillations of atomic inversion (for quadratic scaled detuning parameter , where is the detuning parameter) was built on the basis of formulas obtained[18] by A.A. Karatsuba and E.A. Karatsuba.

See also

- Rabi problem

- Vacuum Rabi oscillation

- Spontaneous emission

- Jaynes-Cummings-Hubbard model

- Caldeira-Leggett model

References

- ↑ E.T. Jaynes; F.W. Cummings (1963). "Comparison of quantum and semiclassical radiation theories with application to the beam maser". Proc. IEEE. 51 (1): 89–109. doi:10.1109/PROC.1963.1664.

- ↑ F.W. Cummings (1965). "Stimulated emission of radiation in a single mode". Phys. Rev. 140 (4A): A1051–A1056. Bibcode:1965PhRv..140.1051C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.140.A1051.

- ↑ J.H. Eberly; N.B. Narozhny; J.J. Sanchez-Mondragon (1980). "Periodic spontaneous collapse and revival in a simple quantum model". Phys. Rev. Lett. 44 (20): 1323–1326. Bibcode:1980PhRvL..44.1323E. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.44.1323.

- ↑ G. Rempe; H. Walther; N. Klein (1987). "Observation of quantum collapse and revival in a one-atom maser". Phys. Rev. Lett. 58 (4): 353–356. Bibcode:1987PhRvL..58..353R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.353. PMID 10034912.

- ↑ S. Haroche; J.M. Raimond (1985). "Radiative properties of Rydberg states in resonant cavities". In D. Bates; B. Bederson. Advances in Atomic and Molecular Physics. 20. New York: Academic Press. p. 350.

- ↑ J.A.C. Gallas; G. Leuchs; H. Walther; H. Figger (1985). "Rydberg atoms: high-resolution spectroscopy and radiation interaction-Rydberg molecules". In D. Bates; B. Bederson. Advances in Atomic and Molecular Physics. 20. New York: Academic Press. p. 414.

- ↑ S.E. Morin; C.C. Yu; T.W. Mossberg (1994). "Strong Atom-Cavity Coupling over Large Volumes and the Observation of Subnatural Intracavity Atomic Linewidths". Phys. Rev. Lett. 73 (11): 1489–1492. Bibcode:1994PhRvL..73.1489M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.73.1489. PMID 10056806.

- ↑ T. Yoshieet al., "Vacuum Rabi splitting with a single quantum dot in a photonic crystal nanocavity", Nature 432, 200 (2004).

- 1 2 Kukliński, J.; Madajczyk, J. "Strong squeezing in the Jaynes-Cummings model". Physical Review A. 37 (8): 3175–3178. Bibcode:1988PhRvA..37.3175K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.37.3175.

- ↑ Gea-Banacloche, J. "Jaynes-Cummings model with quasiclassical fields: The effect of dissipation". Physical Review A. 47 (3): 2221–2234. Bibcode:1993PhRvA..47.2221G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.47.2221.

- ↑ Rodríguez-Lara, B.; Moya-Cessa, H.; Klimov, A. "Combining Jaynes-Cummings and anti-Jaynes-Cummings dynamics in a trapped-ion system driven by a laser". Physical Review A. 71 (2). Bibcode:2005PhRvA..71b3811R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.71.023811.

- ↑ P. Kochanski; Z. Bialynicka-Birula; I. Bialynicki-Birula (2001). "Squeezing of electromagnetic field in a cavity by electrons in Trojan states". Phys. Rev. A. 63: 013811–013811–8. arXiv:quant-ph/0007033

. Bibcode:2001PhRvA..63a3811K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.63.013811.

. Bibcode:2001PhRvA..63a3811K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.63.013811.

- ↑ Kundu, A. "Quantum Integrable Multiatom Matter-Radiation Models With and Without the Rotating-Wave Approximation". Theoretical and Mathematical Physics. 144 (1): 975–984. arXiv:nlin/0409032

. Bibcode:2005TMP...144..975K. doi:10.1007/s11232-005-0125-7.

. Bibcode:2005TMP...144..975K. doi:10.1007/s11232-005-0125-7.

- ↑ Hussin, V.; Nieto, L. M. "Ladder operators and coherent states for the Jaynes-Cummings model in the rotating-wave approximation". Journal of Mathematical Physics. 46 (12): 122102. Bibcode:2005JMP....46l2102H. doi:10.1063/1.2137718.

- ↑ Shore, Bruce W.; Knight, Peter L. "The Jaynes-Cummings Model". Journal of Modern Optics. 40 (7): 1195–1238. Bibcode:1993JMOp...40.1195S. doi:10.1080/09500349314551321.

- ↑ D. Ellinas and I Smyrnakis, "Asymptotics of a quantum random walk driven by an optical cavity", J. Opt. B 7, S152 (2005).

- ↑ S. Stenholm, "Quantum theory of electromagnetic fields interacting with atoms and molecules", Physics Reports, 6(1), 1-121 (1973).

- ↑ A. A. Karatsuba; E. A. Karatsuba (2009). "A resummation formula for collapse and revival in the Jaynes–Cummings model". J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. (42): 195304, 16. Bibcode:2009JPhA...42s5304K. doi:10.1088/1751-8113/42/19/195304.

Further reading

- C.C. Gerry and P.L. Knight (2005). Introductory Quantum Optics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- M. O. Scully and M. S. Zubairy (1997), Quantum Optics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- D. F. Walls and G. J. Milburn (1995), Quantum Optics, Springer-Verlag.