James Whitcomb Riley

| James Whitcomb Riley | |

|---|---|

James Whitcomb Riley, c. 1913 | |

| Born |

October 7, 1849 Greenfield, Indiana, United States |

| Died |

July 22, 1916 (aged 66) Indianapolis, Indiana, United States |

| Resting place | Crown Hill Cemetery |

| Pen name |

Benjamin P. Johnson of Boone |

James Whitcomb Riley (October 7, 1849 – July 22, 1916) was an American writer, poet, and best-selling author. During his lifetime he was known as the "Hoosier Poet" and "Children's Poet" for his dialect works and his children's poetry respectively. His poems tended to be humorous or sentimental, and of the approximately one thousand poems that Riley authored, the majority are in dialect. His famous works include "Little Orphant Annie" and "The Raggedy Man".

Riley began his career writing verses as a sign maker and submitting poetry to newspapers. Thanks in part to an endorsement from poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, he eventually earned successive jobs at Indiana newspaper publishers during the latter 1870s. Riley gradually rose in prominence during the 1880s through his poetry reading tours. He traveled a touring circuit first in the Midwest, and then nationally, holding shows and making joint appearances on stage with other famous talents. Regularly struggling with his alcohol addiction, Riley never married or had children, and created a scandal in 1888 when he became too drunk to perform. He became more popular in spite of the bad press he received, and as a result extricated himself from poorly negotiated contracts that limited his earnings; he quickly became very wealthy.

Riley became a bestselling author in the 1890s. His children's poems were compiled into a book and illustrated by Howard Chandler Christy. Titled the Rhymes of Childhood, the book was his most popular and sold millions of copies. As a poet, Riley achieved an uncommon level of fame during his own lifetime. He was honored with annual Riley Day celebrations around the United States and was regularly called on to perform readings at national civic events. He continued to write and hold occasional poetry readings until a stroke paralyzed his right arm in 1910.

Riley's chief legacy was his influence in fostering the creation of a midwestern cultural identity and his contributions to the Golden Age of Indiana Literature. Along with other writers of his era, he helped create a caricature of midwesterners and formed a literary community that produced works rivaling the established eastern literati. There are many memorials dedicated to Riley, including the James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children.

Early life

Family and background

James Whitcomb Riley was born on October 7, 1849, in the town of Greenfield, Indiana, the third of the six children of Reuben Andrew and Elizabeth Marine Riley.[1][n 1] Riley's father was an attorney, and in the year before Riley's birth, he was elected a member of the Indiana House of Representatives as a Democrat. He developed a friendship with James Whitcomb, the governor of Indiana, after whom he named his son.[2][3] Martin Riley, Riley's uncle, was an amateur poet who occasionally wrote verses for local newspapers. Riley was fond of his uncle who helped influence his early interest in poetry.[4]

Shortly after Riley's birth, the family moved into a larger house in town.[5] Riley was "a quiet boy, not talkative, who would often go about with one eye shut as he observed and speculated."[6] His mother taught him to read and write at home before sending him to the local community school in 1852.[7] He found school difficult and was frequently in trouble. Often punished, he had nothing kind to say of his teachers in his writings. His poem "The Educator" told of an intelligent but sinister teacher and may have been based on one of his instructors.[8][9] Riley was most fond of his last teacher, Lee O. Harris. Harris noticed Riley's interest in poetry and reading and encouraged him to pursue it further.[10]

Riley's school attendance was sporadic, and he graduated from grade eight at age twenty in 1869. In an 1892 newspaper article, Riley confessed that he knew little of mathematics, geography, or science, and his understanding of proper grammar was poor.[11] Later critics, like Henry Beers, pointed to his poor education as the reason for his success in writing; his prose was written in the language of common people which spurred his popularity.[12]

Childhood influences

Riley lived in his parents' home until he was twenty-one years old. At five years old he began spending time at the Brandywine Creek just outside Greenfield. His poems "The Barefoot Boy" and "The Old Swimmin' Hole" referred back to his time at the creek.[6] He was introduced in his childhood to many people who later influenced his poetry. His father regularly brought home a variety of clients and disadvantaged people to give them assistance. Riley's poem "The Raggedy Man" was based on a German tramp his father hired to work at the family home.[2] Riley picked up the cadence and character of the dialect of central Indiana from travelers along the old National Road. Their speech greatly influenced the hundreds of poems he wrote in nineteenth century Hoosier dialect.[13]

Riley's mother frequently told him stories of fairies, trolls, and giants, and read him children's poems. She was very superstitious, and influenced Riley with many of her beliefs. They both placed "spirit rappings" in their homes on places like tables and bureaus to capture any spirits that may have been wandering about. This influence is recognized in many of his works, including "Flying Islands of the Night."[14][15]

As was common at that time, Riley and his friends had few toys and they amused themselves with activities. With his mother's aid, Riley began creating plays and theatricals which he and his friends would practice and perform in the back of a local grocery store. As he grew older, the boys named their troupe the Adelphians and began to have their shows in barns where they could fit larger audiences.[16] Riley wrote of these early performances in his poem "When We First Played 'Show'," where he referred to himself as "Jamesy."[17]

|

"Little Orphant Annie"

A 1912 phonograph recording of Riley reading his famous poem, "Little Orphant Annie." |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Many of Riley's poems are filled with musical references. Riley had no musical education, and could not read sheet music, but learned from his father how to play guitar, and from a friend how to play violin. He performed in two different local bands, and became so proficient on the violin he was invited to play with a group of adult Freemasons at several events. A few of his later poems were set to music and song, one of the most well known being A Short'nin' Bread Song—Pieced Out.[18]

When Riley was ten years old, the first library opened in his hometown. From an early age he developed a love of literature. He and his friends spent time at the library where the librarian read stories and poems to them. Charles Dickens became one Riley's favorites, and helped inspire the poems "St. Lirriper," "Christmas Season," and "God Bless Us Every One."[17]

Riley's father enlisted in the Union Army during the American Civil War, leaving his wife to manage the family home. While he was away, the family took in a twelve-year-old orphan named Mary Alice "Allie" Smith. Smith was the inspiration for Riley's poem "Little Orphant Annie". Riley intended to name the poem "Little Orphant Allie", but a typesetter's error changed the name of the poem during printing.[9][19][20][21]

Finding poetry

Riley's father returned from the war partially paralyzed. He was unable to continue working in his legal practice and the family soon fell into financial distress. The war had a negative physiological effect on him, and his relationship with his family quickly deteriorated. He opposed Riley's interest in poetry and encouraged him to find a different career. The family finances finally disintegrated and they were forced to sell their town home in April 1870 and return to their country farm.[22] Riley's mother was able to keep peace in the family, but after her death in August from heart disease, Riley and his father had a final break. He blamed his mother's death on his father's failure to care for her in her final weeks.[12][23] He continued to regret the loss of his childhood home and wrote frequently of how it was so cruelly snatched from him by the war, subsequent poverty, and his mother's death. After the events of 1870, he developed an addiction to alcohol which he struggled with for the remainder of his life.[12][24]

Becoming increasingly belligerent toward his father, Riley moved out of the family home and briefly had a job painting houses before leaving Greenfield in November 1870. He was recruited as a Bible salesman and began working in the nearby town of Rushville, Indiana.[25] The job provided little income and he returned to Greenfield in March 1871 where he started an apprenticeship to a painter. He completed the study and opened a business in Greenfield creating and maintaining signs. His earliest known poems are verses he wrote as clever advertisements for his customers.[26]

Riley began participating in local theater productions with the Adelphians to earn extra income, and during the winter months, when the demand for painting declined, Riley began writing poetry which he mailed to his brother living in Indianapolis. His brother acted as his agent and offered the poems to the newspaper Indianapolis Mirror for free. His first poem was featured on March 30, 1872 under the pseudonym "Jay Whit."[27] Riley wrote more than twenty poems to the newspaper, including one that was featured on the front page.[27][28]

In July 1872, after becoming convinced sales would provide more income than sign painting, he joined the McCrillus Company based in Anderson, Indiana.[29] The company sold patent medicines that they marketed in small traveling shows around Indiana. Riley joined the act as a huckster, calling himself the "Painter Poet". He traveled with the act, composing poetry and performing at the shows.[30][31] After his act he sold tonics to his audience, sometimes employing dishonesty. During one stop, Riley presented himself as a formerly blind painter who had been cured by a tonic, using himself as evidence to encourage the audience to purchase his product.[32]

Riley began sending poems to his brother again in February 1873. About the same time he and several friends began an advertisement company.[33] The men traveled around Indiana creating large billboard-like signs on the sides of buildings and barns and in high places that would be visible from a distance.[34] The company was financially successful, but Riley was continually drawn to poetry. In October he traveled to South Bend where he took a job at Stockford & Blowney painting verses on signs for a month; the short duration of his job may have been due to his frequent drunkenness at that time.[35]

In early 1874, Riley returned to Greenfield to become a writer full-time.[36] In February he submitted a poem entitled "At Last" to the Danbury News, a Connecticut newspaper.[37] The editors accepted his poem, paid him for it, and wrote him a letter encouraging him to submit more. Riley found the note and his first payment inspiring.[38] He began submitting poems regularly to the editors,[39] but after the newspaper shut down in 1875, Riley was left without a paying publisher. He began traveling and performing with the Adelphians around central Indiana to earn an income while he searched for a new publisher. In August 1875 he joined another traveling tonic show run by the Wizard Oil Company.[40][n 2]

Early career

Newspaper work

Riley began sending correspondence to the famous American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow during late 1875 seeking his endorsement to help him start a career as a poet.[41] He submitted many poems to Longfellow, whom he considered to be the greatest living poet. Not receiving a prompt response, he sent similar letters to John Townsend Trowbridge, and several other prominent writers asking for an endorsement.[42] Longfellow finally replied in a brief letter, telling Riley that "I have read [the poems] in great pleasure, and think they show a true poetic faculty and insight."[43][44] Riley carried the letter with him everywhere and, hoping to receive a job offer and to create a market for his poetry, he began sending poems to dozens of newspapers touting Longfellow's endorsement. Among the newspapers to take an interest in the poems was the Indianapolis Journal, a major Republican Party metropolitan newspaper in Indiana. Among the first poems the newspaper purchased from Riley were "Song of the New Year", "An Empty Nest", and a short story entitled "A Remarkable Man".[45]

The editors of the Anderson Democrat discovered Riley's poems in the Indianapolis Journal and offered him a job as a reporter in February 1877.[46][47] Riley accepted. He worked as a normal reporter gathering local news, writing articles, and assisting in setting the typecast on the printing press. He continued to write poems regularly for the newspaper and to sell other poems to larger newspapers.[48] During the year Riley spent working in Anderson, he met and began to court Edora Mysers. The couple became engaged, but terminated the relationship after they decided against marriage in August.[49]

After a rejection of his poems by an eastern periodical, Riley began to formulate a plot to prove his work was of good quality and that it was being rejected only because his name was unknown in the east. Riley authored a poem imitating the style of Edgar Allan Poe and submitted it to the Kokomo Dispatch under a fictitious name claiming it was a long lost Poe poem. The Dispatch published the poem and reported it as such.[50][51] Riley and two other men who were part of the plot waited two weeks for the poem to be published by major newspapers in Chicago, Boston, and New York to gauge their reaction; they were disappointed. While a few newspapers believed the poem to be authentic, the majority did not, claiming the quality was too poor to be authored by Poe.[52] An employee of the Dispatch learned the truth of the incident and reported it to the Kokomo Tribune, which published an expose that outed Riley as a conspirator behind the hoax. The revelation damaged the credibility of the Dispatch and harmed Riley's reputation.[53][54]

In the aftermath of the Poe plot, Riley was dismissed from the Democrat, so he returned to Greenfield to spend time writing poetry.[55] Back home, he met Clara Louise Bottsford, a school teacher boarding in his father's home. They found they had much in common, particularly their love of literature. The couple began a twelve-year intermittent relationship which would be Riley's longest lasting.[56] In mid-1878 the couple had their first breakup, caused partly by Riley's alcohol addiction. The event led Riley to make his first attempt to give up liquor. He joined a local temperance organization, but quit after a few weeks.[57]

Performing poet

Without a steady income, his financial situation began to deteriorate. He began submitting his poems to more prominent literary magazines, including Scribner's Monthly, but was informed that although he showed promise, his work was still short of the standards required for use in their publications.[58][59] Locally, he was still dealing with the stigma of the Poe plot. The Indianapolis Journal and other newspapers refused to accept his poetry, leaving Riley desperate for income. In January 1878 on the advice of a friend, Riley paid an entrance fee to join a traveling lecture circuit where he could give poetry readings. In exchange, he received a portion of the profit his performances earned. Such circuits were popular at the time, and Riley quickly earned a local reputation for his entertaining readings.[60]

In August 1878, Riley followed Indiana Governor James D. Williams as speaker at a civic event in a small town near Indianapolis. He recited a recently composed poem, "A Childhood Home of Long Ago," telling of life in pioneer Indiana. The poem was well received and was given good reviews by several newspapers.[61]

"Flying Islands of the Night" is the only play that Riley wrote and published. Authored while Riley was traveling with the Adelphians, but never performed, the play has similarities to A Midsummer Night's Dream, which Riley may have used as a model.[62] Flying Islands concerns a kingdom besieged by evil forces of a sinister queen who is defeated eventually by an angel-like heroine.[63] Most reviews were positive. Riley published the play and it became popular in the central Indiana area during late 1878, helping Riley to convince newspapers to again accept his poetry. In November 1879 he was offered a position as a columnist at the Indianapolis Journal and accepted after being encouraged by E.B. Matindale, the paper's chief editor.[64]

Although the play and his newspaper work helped expose him to a wider audience, the chief source of his increasing popularity was his performances on the lecture circuit. He made both dramatic and comedic readings of his poetry, and by early 1879 could guarantee large crowds whenever he performed.[65] In an 1894 article, Hamlin Garland wrote that Riley's celebrity resulted from his reading talent, saying "his vibrant individual voice, his flexible lips, his droll glance, united to make him at once poet and comedian—comedian in the sense in which makes for tears as well as for laughter."[66] Although he was a good performer, his acts were not entirely original in style; he frequently copied practices developed by Samuel Clemens and Will Carleton.[67] His tour in 1880 took him to every city in Indiana where he was introduced by local dignitaries and other popular figures, including Maurice Thompson with whom he began to develop a close friendship.[68]

Developing and maintaining his publicity became a constant job, and received more of his attention as his fame grew. Keeping his alcohol addiction secret, maintaining the persona of a simple rural poet and a friendly common person became most important.[69] Riley identified these traits as the basis of his popularity during the mid-1880s, and wrote of his need to maintain a fictional persona.[67] He encouraged the stereotype by authoring poetry he thought would help build his identity. He was aided by editorials he authored and submitted to the Indianapolis Journal offering observations on events from his perspective as a "humble rural poet".[70] He changed his appearance to look more mainstream, and began by shaving his mustache off and abandoning the flamboyant dress he employed in his early circuit tours.[71]

By 1880 his poems were beginning to be published nationally and were receiving positive reviews. "Tom Johnson's Quit" was carried by newspapers in twenty states, thanks in part to the careful cultivation of his popularity.[70] Riley became frustrated that despite his growing acclaim, he found it difficult to achieve financial success.[72] In the early 1880s, in addition to his steady performing, Riley began producing many poems to increase his income. Half of his poems were written during the period. The constant labor had adverse effects on his health, which was worsened by his drinking. At the urging of Maurice Thompson, he again attempted to stop drinking liquor, but was only able to give it up for a few months.[73]

Indianapolis Journal

Newspaper poet

Riley moved to Indianapolis at the end of 1879 to begin his employment with the Journal. It was the only metropolitan newspaper in Indianapolis with daily editions, and had wide readership. For the newspaper he wrote a regular society column that often included verses of poetry.[74][75] Thereafter Riley met many prominent people, and began a close friendship with Eugene V. Debs.[76] Debs enjoyed Riley's works and often complimented his sentiments.[77] Riley had been using the pseudonym "Jay Whit" since he started authoring poetry, but finally began to write under his own name in April 1881.[78]

Riley renewed his relationship with Bottsford in 1880, and the two corresponded frequently. Their relationship remained unstable, but Riley became deeply attached to her. She inspired his poem "The Werewife," which told of a perfect wife who could suddenly become a demonic monster.[79] Bottsford pressed Riley for marriage several times, but Riley refused.[80] They broke off their relationship a second time in 1881 when she discovered his correspondence with two other women,[81] and found that he had taken a secret vacation to Wisconsin with one of them.[82]

Riley's alcohol addiction influenced some of his poems during his time working for the Journal, including "On Quitting California," "John Golliher's Third Womern," [sic] and "The Dismal Fate of Tit." Each made references to the delirium caused by drinking.[83] Although Riley rarely published anything controversial, some of his poems published from the same period, including "Afterwhiles", allude to drug usage and make vague sexual references.[84] During the early 1880s, Riley still made submissions to the elite literary periodicals, but continued to be rejected. Riley found the rejection discouraging, but persevered. He believed he would never be recognized as a true literary figure until one of the prestigious periodicals published his work.[85]

Lyceum circuit

Riley made occasional reading tours around Indiana, and in August 1880 was invited to perform at Asbury University. His performance there so impressed the local Phi Kappa Psi chapter, he was invited to join as an honorary member.[86] Through the fraternity he met Robert Jones Burdette, a writer and minister in the Indianapolis area. Burdette was a member of the Redpath Lyceum Bureau of Boston, a prominent lecture circuit whose regular speakers included Ralph Waldo Emerson.[87] Burdette encouraged Riley to join the circuit through its Chicago branch.[88] Riley's accumulated debt and low income began causing him trouble in 1881, and he decided rejoining a lecture circuit would provide much needed funds.[89] His agreement for continued employment with the circuit depended on his ability to draw audiences during the first season, beginning in April 1881. He succeeded, drawing the largest crowds in Chicago and Indianapolis.[90]

Because of his success in the midwest, the circuit leaders invited him to make an east coast tour, starting in Boston at the Tremont Temple in February 1882.[91] Riley agreed, signing a ten-year agreement and granting half his receipts to his agent.[92] Before his performance, he traveled to Longfellow's home in Massachusetts and convinced him to agree to a meeting. Their brief meeting was one of Riley's fondest memories, and he wrote a lengthy article on it after Longfellow's death only a month later.[93][94] Longfellow encouraged Riley to focus on poetry, and gave him advice for his upcoming performance. At the performance, Riley was well received and his poems were greeted with laughter and given praise in the city's newspaper reviews.[95][96] Boston was the literary center of the United States at the time, and Riley's impression on the city's literary community helped him finally to get his work accepted by prestigious periodicals. The Century Magazine was the first such periodical to accept his work, running "In Swimming-Time" in its September 1883 issue.[97] Until the 1890s, it remained the only major literary magazine to publish Riley's work. Knowing the high standards of the magazine, Riley reserved his best work each year to submit, including one of his favorites, "The Old Man and Jim" in 1887.[98]

By the end of 1882, Riley's finances began to improve dramatically, thanks largely to the income from his performances.[99] During 1883 he began writing his "Boone County" poems by the pseudonym "Benjamin F. Johnson of Boone." The poems were almost entirely written in dialect and emphasized topics of rural life during the early nineteenth century, often employing nostalgia and the simplicity of country life as elements. "The Old Swimmin'-Hole" and "When the Frost Is on the Punkin'" were the most popular, and helped earn the entire series critical acclaim. The topics were popular with readers, reminding many of them of their childhood.[100] Merrill, Meigs & Company (later renamed Bobbs-Merrill Company) approached Riley to compile the poems into a book. Riley agreed and printing of his first book began in August 1883, titled "The Old Swimmin'-Hole and 'Leven More Poems". The book's popularity necessitated a second printing before the end of the year.[101] During this period Riley determined that his most popular poems were those on topics of rural life, and he began to use that as a common theme throughout his future work.[102]

The income from Riley's book allowed him to ease his busy work schedule; he submitted articles to the Journal less frequently and made fewer lecture stops. His poems became fewer but the quality of his poetry improved; he wrote his most famous poems during the mid-1880s, including "Little Orphant Annie" [sic].[103] Riley attempted to secure a new job at a periodical and leave the Journal, but the magazines to which he submitted would not hire him unless he was willing to relocate. Riley was steadfast in his refusal to leave Indiana, and told reporters that his rural home was his inspiration and to leave would ruin his poetry.[104]

Riley renewed his relationship with Bottsworth for a third and final time in 1883. The two corresponded frequently and had secret lovers' rendezvous. He stopped visiting other women and their relationship became more dedicated and stable.[105] Bottsworth, however, became convinced Riley was seeing another woman, and they terminated their relationship in January 1885.[106] Riley's sister, Mary, had become a close friend of Bottsworth and scolded him for his mistreatment of her. Her reputation was tarnished by the affair and she found it difficult to find employment once their relationship ended.[107]

In 1884, Riley made another tour of the major cities in the eastern United States.[108] Following the lectures, he began compiling a second book of poetry. He completed it during July and Bowen-Merrill published it in December with the title The Boss Girl, A Christmas Story and Other Sketches.[109] The book, which contained humorous poetry and short stories, received mixed reviews. It was popular around Indiana, where the majority of its copies were sold. One reviewer, however, called the poems "weird, nightmarish, and eerie," and compared them to Edgar Allan Poe's works.[110][111]

While Riley was working on his book, he was unexpectedly invited by James B. Pond, the agent for many of the nations major performers, to join a one-hundred nights' engagement in New York City in a show that included Samuel Clemens and Dudley Warner.[112] Riley, however, was unable to agree with the Redpath Bureau who had to authorize any other performance under the terms of their contract. Riley believed his contract with Redpath Bureau was limiting his opportunities, and his relationship with his agent became strained.[113][114]

Western Association of Writers

Due partly to the limited success of his latest book outside Indiana, Riley was persuaded to begin working with other midwestern writers to attempt to form an association to promote their work. Popular Indiana writer Lew Wallace, author of Ben-Hur, was a major promoter of the effort.[115] During 1885, more than one hundred writers joined the group. They held their first meeting in July, naming themselves the Western Association of Writers. At the meeting Maurice Thompson was named president, and Riley vice president.[116] The association never succeeded in its goals of creating a powerful advertising force, but became a social club and a rival literary community to the eastern writing establishment. Riley was disappointed with the shortcomings of the group, but came to depend on its regular meetings as a escape from his normally hectic schedule.[117]

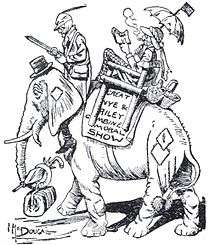

Through the association, Riley became acquainted with most of the notable writers in the midwestern United States, including humorist Edgar Wilson Nye of Chicago. After completing his lecture circuit in 1885, Riley formed a partnership with Nye and his agent to begin a new tour. The Redpath Bureau agreed to allow Riley to tour with Nye, provided he maintained his financial agreements with them.[118] In addition to touring, Riley and Nye collaborated to write a book, Nye and Riley's Railway Guide, a collection of humorous anecdotes and poems intended to parody popular tourist literature of the day. Published in 1888, the book was somewhat successful and had three reprints.[98]

In October 1887, Riley and the association joined with other writers to petition the United States Congress to attempt to negotiate international treaties to protect American copyrights abroad. The group became known as the International Copyright League and had significant success in its efforts. When traveling to one of the league's meetings in New York City that year, Riley was struck by Bell's palsy. He recovered after three weeks, but remained secluded to hide the effects of the sickness which he believed was caused by his alcohol addiction. He made another attempt to stop drinking alcohol with the help of a minister, but again soon returned to his old habit.[119]

After recovering, Riley remained briefly in New York to participate in a show at Chickering Hall with Edgar Nye, Samuel Clemens, and several others. Riley was introduced by James Russell Lowell before his performance, and Lowell gave Riley a glowing endorsement to the crowd. Riley's poetry brought both tears and laughter according to The New York Sun. Critic Edmund Clarence Stedman, one of the foremost literary critics of the era, was present and wrote that Riley's dialect poems were the finest he had ever heard, "in which a homely dramatis [sic] persona's heart is laid open by subtle indirect, absolutely sure and tender" poetry.[120] As a result of his New York performance, his name and picture were carried in all the major eastern papers and he quickly became well known throughout the United States. Sales of The Boss Girl increased, resulting in the fifth and largest printing, and Riley finally began to achieve the widespread fame he sought.[60]

Clemens disliked being upstaged by Riley, and thereafter attempted to avoid any future joint performances with him. According to one review, Clemens "shriveled up into a bitter patch of melancholy in the fierce light of Mr. Riley's humour."[121]

After returning home from his tour in early 1888, Riley finished compiling his third book, titled Old-Fashioned Roses. Arranged to appeal to British readers, it included only a few of his dialect poems and consisted mostly of sonnets. The book reprinted many poems Riley had already published, but included some new ones he wrote specifically for the book, including "The Days Gone By," "The Little White Hearse," and "The Serenade." The book was Riley's favorite because it included his finest works and was published by the prestigious Longmans, Green Publishers in a high quality binding and print.[122][123]

In late 1888 he finished work on a fourth book, Pipes o' Pan at Zekesbury which was released to great acclaim in the United States. Based on a fictional town in Indiana, Riley presented many stories and poems about its citizens and way of life. It received mixed reviews among literary critics who wrote of it that Riley's stories were not of the same quality as his poetry. The book was very popular with the public and went through numerous reprints.[124][125]

Riley was quickly becoming wealthy from his books and touring, earning nearly $20,000 in 1888. He no longer needed his job at the journal, and he left the job near the end of that year. The newspaper had served to earn him fame and had published hundreds of his articles, stories, and poems.[126]

National fame

Politics

In March 1888, Riley traveled to Washington, D.C. where he had dinner at the White House with other members of the International Copyright League and President of the United States Grover Cleveland. Riley made a brief performance for the dignitaries at the event before speaking about the need for international copyright protections. Cleveland was enamored by Riley's performance and invited him back for a private meeting during which the two men discussed cultural topics.[127] In the 1888 Presidential Election campaign, Riley's acquaintance Benjamin Harrison was nominated as the Republican candidate. Although Riley had shunned politics for most of his life, he gave Harrison a personal endorsement and participated in fund-raising events and vote stumping. The election was exceptionally partisan in Indiana, and Riley found the atmosphere of the campaign stressful; he vowed never to become involved with politics again.[128]

Upon Harrison's election, he suggested Riley be named the national poet laureate, but Congress failed to act on the request. Riley was still honored by Harrison and visited him at the White House on several occasions to perform at civic events.[129]

Pay problems and scandal

Riley and Nye made arrangements with James Pond to make two national tours during 1888 and 1889.[130] The tours were popular and generally sold out, with hundreds having to be turned away. The shows were usually forty-five minutes to an hour long and featured Riley reading often humorous poetry interspersed by stories and jokes from Nye. The shows were informal and the two men adjusted their performances based on their audiences reactions. Riley memorized forty of his poems for the shows to add to his own versatility.[129][131] Many prominent literary and theatrical people attended the shows. At a New York City show in March 1888, Augustin Daly was so enthralled by the show he insisted on hosting the two men at a banquet with several leading Broadway theatre actors.[132]

Despite Riley serving as the act's main draw, he was not permitted to become an equal partner in the venture. Nye and Pond both received a percentage of the net profit, while Riley was paid a flat rate for each performance.[133] In addition, because of Riley's past agreements with the Redpath Lyceum Bureau, he was required to pay half of his fee to his agent Amos Walker. This caused the other men to profit more than Riley from his own work.[124]

To remedy this situation, Riley hired his brother-in-law Henry Eitel, an Indianapolis banker, to manage his finances and act on his behalf to try and extricate him from his contract. Despite discussions and assurances from Pond that he would work to address the problem, Eitel had no success. Pond ultimately made the situation worse by booking months of solid performances, not allowing Riley and Nye a day of rest. These events affected Riley physically and emotionally; he became despondent and began his worst period of alcoholism. During November 1889, the tour was forced to cancel several shows after Riley became severely inebriated at a stop in Madison, Wisconsin.[134][135]

Walker began monitoring Riley and denying him access to liquor, but Riley found ways to evade Walker. At a stop at the Masonic Temple Theatre in Louisville, Kentucky, in January 1890, Riley paid the hotel's bartender to sneak whiskey to his room.[136] He became too drunk to perform, and was unable to travel to the next stop. Nye terminated the partnership and tour in response. The reason for the breakup could not be kept secret, and hotel staff reported to the Louisville Courier-Journal that they saw Riley in a drunken stupor walking around the hotel.[137] The story made national news and Riley feared his career was ruined.[138]

He secretly left Louisville at night and returned to Indianapolis by train. Eitel defended Riley to the press in an effort to gain sympathy for Riley, explaining the abusive financial arrangements his partners had made. Riley however refused to speak to reporters and hid himself for weeks.[139] Much to Riley's surprise, the news reports made him more popular than ever.[140] Many people thought the stories were exaggerated, and Riley's carefully cultivated image made it difficult for the public to believe he was an alcoholic. Riley had stopped sending poetry to newspapers and magazines in the aftermath, but they soon began corresponding with him requesting that he resume writing. This encouraged Riley, and he made another attempt to give up liquor as he returned to his public career.[141]

The negative press did not end however, as Nye and Pond threatened to sue Riley for causing their tour to end prematurely. They claimed to have lost $20,000. Walker threatened a separate suit demanding $1,000. Riley hired Indianapolis lawyer William P. Fishback to represent him and the men settled out of court.[142] The full details of the settlement were never disclosed, but whatever the case, Riley finally extricated himself from his old contracts and became a free agent. The exorbitant amount Riley was being sued for only reinforced public opinion that Riley had been mistreated by his partners, and helped him maintain his image. Nye and Riley remained good friends, and Riley later wrote that Pond and Walker were the source of the problems.[143]

Riley's poetry had become popular in Britain, in large part due to his book Old-Fashioned Roses. In May 1891 he traveled to England to make a tour and what he considered a literary pilgrimage. He landed in Liverpool and traveled first to Dumfries, Scotland, the home and burial place of Robert Burns. Riley had long been compared to Burns by critics because they both used dialect in their poetry and drew inspiration from their rural homes.[144][145] He then traveled to Edinburgh, York, and London, reciting poetry for gatherings at each stop. Augustin Daly arranged for him to give a poetry reading to prominent British actors in London.[114] Riley was warmly welcomed by its literary and theatrical community and he toured places that Shakespeare had frequented.[146]

Riley quickly tired of traveling abroad and began longing for home, writing to his nephew that he regretted having left the United States. He curtailed his journey and returned to New York City in August.[147][148] He spent the next months in his Greenfield home attempting to write an epic poem, but after several attempts gave up, believing he did not possess the ability.[149]

By 1890, Riley had authored almost all of his famous poems. The few poems he did write during the 1890s were generally less well received by the public.[147] As a solution, Riley and his publishers began reusing poetry from other books and printing some of his earliest works. When Neighborly Poems was published in 1891, a critic working for the Chicago Tribune pointed out the use of Riley's earliest works, commenting that Riley was using his popularity to push his crude earlier works onto the public only to make money.[150][151] Riley's newest poems published in the 1894 book Armazindy received very negative reviews that referred to poems like "The Little Dog-Woggy" and "Jargon-Jingle" as "drivel" and to Riley as a "worn out genius."[150] Most of his growing number of critics suggested that he ignored the quality of the poems for the sake of making money.[150]

Last tours

Although Riley was wealthy from his books, he was able to triple his annual income by touring. He found the lure hard to resist and decided to return to the lecture circuit in 1892. He hired William C. Glass to assist Henry Eitel in managing his affairs. While Eitel handled the finances, Glass worked to organize his lecture tours.[152] Glass worked closely with Riley's publishers to have his tours coincide with the release of new books, and ensured his tours were geographically varied enough to maintain his popularity in all regions of the nation. He was careful not to book busy schedules; Riley only performed four times a week and the tours were short, lasting only three months.[153]

During his 1893 tour, Riley lectured mostly in the western United States, and in his 1894 tour in the east. His performances were major events, and generally sold out within days of their announcements. In 1894 he allowed author Douglass Sherley to join his tour. Sherley was a millionaire who published his own books. The literary community had dismissed his work, but Riley was instrumental in helping him to be accepted.[154]

In 1895 Riley made his last tour, making stops in most of the major cities in the United States.[155] Advertised as his final performances, there was incredible demand for tickets and Riley performed before his largest audiences during the tour. He and Sherley continued a show very similar to those that he and Nye had done. Riley often lamented the lack of change in the program, but found when he tried to introduce new material, or left out any of his most popular poems, the crowds would demand encores until he agreed to recite their favorites.[156]

Children's poet

Following the death of his father in 1894, Riley began regretting his choice not to marry or have children.[154] To compensate for the lack of his own children, he became a doting uncle, showering gifts on his nieces and nephews. He had repurchased his childhood home in 1893 and allowed his divorced sister, Mary, his widowed sister-in-law, Julia, and their daughters to live in the home.[157] He provided for all their needs and spent the summer months of 1893 living with them. He took his nephew Edmund Eital as a personal secretary and gave him a $50,000 wedding gift in 1912. Riley was well loved by his family.[158]

Riley returned to live near Indianapolis later in 1893, boarding in a private home in the Lockerbie district, then a small suburb. He developed a close friendship with his landlords, the Nickum and Holstein families. The home became a destination for local schoolchildren to whom Riley would regularly recite poetry and tell stories. Riley's friends frequently visited his home, and he developed a closer relationship with Eugene Debs.[159]

The same year, he began compiling his poems of most interest to children into a new book entitled Rhymes of Childhood. The book was richly illustrated by Howard Chandler Christy and Riley authored a few new poems for the book under the pseudonym "Uncle Sydney."[160] Rhymes of Childhood became Riley's best selling book, and sold millions of copies. It has remained in print continually since 1912, and helped earn Riley the nickname the "Children's Poet." Even Riley's rival, Clemens, commented that the book was "charming" and made him weep for his "lost youth."[161]

Later life

National poet

Riley had become very wealthy by the time he ended touring in 1895, and was earning $1,000 a week.[162] Although he retired, he continued to make minor appearances. In 1896, Riley performed four shows in Denver.[163][164] Most of the performances of his later life were at civic celebrations. He was a regular speaker at Decoration Day events and delivered poetry before the unveiling of monuments in Washington, D.C. Newspapers began referring to him as the "National Poet", "the poet laureate of America", and "the people's poet laureate".[156] Riley wrote many of his patriotic poems for such events, including "The Soldier", "The Name of Old Glory", and his most famous such poem, "America!". The 1902 poem "America, Messiah of Nations" was written and read by Riley for the dedication of the Indianapolis Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument.[165][166]

The only new poetry Riley published after the end of the century were elegies for famous friends. The poetic qualities of the poems were often poor, but they contained many popular sentiments concerning the deceased. Among those he eulogized were Benjamin Harrison, Lew Wallace, and Henry Lawton. Because of the poor quality of the poems, his friends and publishers requested that he stop writing them, but he refused.[167]

In 1897, Riley's publishers suggested that he create a multi-volume series of books containing his complete life works.[168] With the help of his nephew, Riley began working to compile the books, which eventually totaled sixteen volumes and were finally completed in 1914. Such works were uncommon during the lives of writers, attesting to the uncommon popularity Riley had achieved.[169][170]

His works had become staples for Ivy League literature courses and universities began offering him honorary degrees. The first was Yale in 1902, followed by a Doctorate of Letters from the University of Pennsylvania in 1904. Wabash College and Indiana University granted him similar awards.[171] In 1908 he was elected member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and in 1912 they conferred upon him a special medal for poetry.[169][172]

Riley was influential in helping other poets start their careers, having particularly strong influences on Hamlin Garland, William Allen White, and Edgar Lee Masters. He discovered aspiring African American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar in 1892. Riley thought Dunbar's work was "worthy of applause", and wrote him letters of recommendation to help him get his work published.[169]

Declining health

In 1901, Riley's doctor diagnosed him with neurasthenia, a nervous disorder, and recommended long periods of rest as a cure.[173] Riley remained ill for the rest of his life and relied on his landlords and family to aid in his care. During the winter months he moved to Miami, Florida, and during summer spent time with his family in Greenfield. He made only a few trips during the decade, including one to Mexico in 1906. He became very depressed by his condition, writing to his friends that he thought he could die at any moment, and often used alcohol for relief.[174]

In March 1909, Riley was stricken a second time with Bell's palsy, and partial deafness, the symptoms only gradually eased over the course of the year.[175] Riley was a difficult patient, and generally refused to take any medicine except the patent medicines he had sold in his earlier years; the medicines often worsened his conditions, but his doctors could not sway his opinion.[176] On July 10, 1910 he suffered a stroke that paralyzed the right side of his body. Hoping for a quick recovery, his family kept the news from the press until September. Riley found the loss of use of his writing hand the worst part of the stroke, which served only to further depress him.[174][177] With his health so poor, he decided to work on a legacy by which to be remembered in Indianapolis. In 1911 he donated land and funds to build a new library on Pennsylvania Avenue.[178] By 1913, with the aid of a cane, Riley began to recover his ability to walk. His inability to write, however, nearly ended his production of poems. George Ade worked with him from 1910 through 1916 to write his last five poems and several short autobiographical sketches as Riley dictated. His publisher continued recycling old works into new books, which remained in high demand.[178]

Since the mid-1880s, Riley had been the nation's most read poet, a trend that accelerated at the turn of the century. In 1912 Riley recorded readings of his most popular poetry to be sold by Victor Records. Riley was the subject of three paintings by T. C. Steele. The Indianapolis Arts Association commissioned a portrait of Riley to be created by world famous painter John Singer Sargent. Riley's image became a nationally known icon and many businesses capitalized on his popularity to sell their products; Hoosier Poet brand vegetables became a major trade-name in the midwest.[179]

In 1912, the governor of Indiana instituted Riley Day on the poet's birthday. Schools were required to teach Riley's poems to their children, and banquet events were held in his honor around the state. In 1915 and 1916 the celebration was national after being proclaimed in most states. The annual celebration continued in Indiana until 1968.[180] In early 1916 Riley was filmed as part of a movie to celebrate Indiana's centennial, the video is on display at the Indiana State Library.[181][182]

Death and legacy

On July 22, 1916, Riley suffered a second stroke. He recovered enough during the day to speak and joke with his companions. He died before dawn the next morning, July 23.[183] Riley's death shocked the nation and made front page headlines in major newspapers.[184] President Woodrow Wilson wrote a brief note to Riley's family offering condolences on behalf the entire nation. Indiana Governor Samuel M. Ralston offered to allow Riley to lie in state at the Indiana Statehouse—Abraham Lincoln being the only other person to have previously received such an honor.[185] During the ten hours he lay in state on July 24, more than thirty-five thousand people filed past his bronze casket; the line was still miles long at the end of the day and thousands were turned away. The next day a private funeral ceremony was held and attended by many dignitaries. A large funeral procession then carried him to Crown Hill Cemetery where he was buried in a tomb at the top of the hill, the highest point in the city of Indianapolis.[186]

Within a year of Riley's death many memorials were created, including several by the James Whitcomb Riley Memorial Association. The James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children was created and named in his honor by a group of wealthy benefactors and opened in 1924. In the following years, other memorials intended to benefit children were created, including Camp Riley for youth with disabilities.[187][188]

The memorial foundation purchased the poet's Lockerbie home in Indianapolis and it is now maintained as a museum. The James Whitcomb Riley Museum Home is the only late-Victorian home in Indiana that is open to the public and the United States' only late-Victorian preservation, featuring authentic furniture and decor from that era. His birthplace and boyhood home, now the James Whitcomb Riley House, is preserved as a historical site.[189] A Liberty ship, commissioned April 23, 1942, was christened the SS James Whitcomb Riley. It served with the United States Maritime Commission until being scrapped in 1971.

James Whitcomb Riley High School opened in South Bend, Indiana in 1924. In 1950, there was a James Whitcomb Riley Elementary School in Hammond, Indiana, but it was torn down in 2006. East Chicago, Indiana had a Riley School at one time, as did neighboring Gary, Indiana and Anderson, Indiana. One of New Castle, Indiana's elementary schools is named for Riley[190] as is the road[191] on which it is located along with Riley Elementary School in La Porte, Indiana. The former Greenfield High School was converted to Riley Elementary School and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986.

In 1940, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 10-cent stamp honoring Riley.[192]

As a lasting tribute, the citizens of Greenfield hold a festival every year in Riley's honor. Taking place the first or second weekend of October, the "Riley Days" festival traditionally commences with a flower parade in which local school children place flowers around Myra Reynolds Richards' statue of Riley on the county courthouse lawn, while a band plays lively music in honor of the poet. Weeks before the festival, the festival board has a queen contest. The 2010–2011 queen was Corinne Butler. The pageant has been going on many years in honor of the Hoosier poet[193]

According to historian Elizabeth Van Allen, Riley was instrumental in helping form a midwestern cultural identity. The midwestern United States had no significant literary community before the 1880s.[194] The works of the Western Association of Writers, most notably those of Riley and Wallace, helped create the midwest's cultural identity and create a rival literary community to the established eastern literari. For this reason, and the publicity Riley's work created, he was commonly known as the "Hoosier Poet."[195][196]

Critical reception and style

Riley was among the most popular writers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, known for his "uncomplicated, sentimental, and humorous" writing.[197] Often writing his verses in dialect, his poetry caused readers to recall a nostalgic and simpler time in earlier American history. This gave his poetry a unique appeal during a period of rapid industrialization and urbanization in the United States. Riley was a prolific writer who "achieved mass appeal partly due to his canny sense of marketing and publicity."[197] He published more than fifty books, mostly of poetry and humorous short stories, and sold millions of copies.[197]

Riley is often remembered for his most famous poems, including the "The Raggedy Man" and "Little Orphant Annie". Many of his poems, including those, where partially autobiographical, as he used events and people from his childhood as an inspiration for subject matter.[197] His poems often contained morals and warnings for children, containing messages telling children to care for the less fortunate of society. David Galens and Van Allen both see these messages as Riley's subtle response to the turbulent economic times of the Gilded Age and the growing progressive movement.[198] Riley believed that urbanization robbed children of their innocence and sincerity, and in his poems he attempted to introduce and idolize characters who had not lost those qualities.[199] His children's poems are "exuberant, performative, and often display Riley's penchant for using humorous characterization, repetition, and dialect to make his poetry accessible to a wide-ranging audience."[197][200]

Although hinted at indirectly in some poems, Riley wrote very little on serious subject matter, and actually mocked attempts at serious poetry. Only a few of his sentimental poems concerned serious subjects. "Little Mandy's Christmas-Tree", "The Absence of Little Wesley", and "The Happy Little Cripple" were about poverty, the death of a child, and disabilities. Like his children's poems, they too contained morals, suggesting society should pity the downtrodden and be charitable.[197][200]

Riley wrote gentle and romantic poems that were not in dialect. They generally consisted of sonnets and were strongly influenced by the works of John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. His standard English poetry was never as popular as his Hoosier dialect poems.[197] Still less popular were the poems Riley authored in his later years; most were to commemorate important events of American history and to eulogize the dead.[197]

Riley's contemporaries acclaimed him "America's best-loved poet".[197][200] In 1920, Henry Beers lauded the works of Riley "as natural and unaffected, with none of the discontent and deep thought of cultured song."[197] Samuel Clemens, William Dean Howells, and Hamlin Garland, each praised Riley's work and the idealism he expressed in his poetry. Only a few critics of the period found fault with Riley's works. Ambrose Bierce criticized Riley for his frequent use of dialect. Bierce accused Riley of using dialect to "cover up [the] faulty construction" of his poems.[197] Edgar Lee Masters found Riley's work to be superficial, claiming it lacked irony and that he had only a "narrow emotional range".[197] By the 1930s popular critical opinion towards Riley's works began to shift in favor of the negative reviews. In 1951, James T. Farrell said Riley's works were "cliched." Galens wrote that modern critics consider Riley to be a "minor poet, whose work—provincial, sentimental, and superficial though it may have been—nevertheless struck a chord with a mass audience in a time of enormous cultural change."[197] Thomas C. Johnson wrote that what most interests modern critics was Riley's ability to market his work, saying he had a unique understanding of "how to commodify his own image and the nostalgic dreams of an anxious nation."[197]

Among the earliest widespread criticisms of Riley were opinions that his dialect writing did not actually represent the true dialect of central Indiana. In 1970 Peter Revell wrote that Riley's dialect was more similar to the poor speech of a child rather than the dialect of his region. Revell made extensive comparison to historical texts and Riley's dialect usage. Philip Greasley wrote that while "some critics have dismissed him as sub-literary, insincere, and an artificial entertainer, his defenders reply that an author so popular with millions of people in different walks of life must contribute something of value, and that his faults, if any, can be ignored."[200]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Coincidentally, Riley was born on the day of Edgar Allan Poe's death. (see: Van Allen, p. 2)

- ↑ Riley remained with the Wizard Oil Company until late 1877. During his time there he made the acquaintance of Paul Dresser. (see: Crowder, p. 68)

Footnotes

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 17

- 1 2 Van Allen, p. 29

- ↑ Crowder, p. 30

- ↑ Crowder, p. 31

- ↑ Crowder, p. 28

- 1 2 Van Allen, p. 35

- ↑ Van Allen, 39

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 40

- 1 2 Bodenhamer, 1195

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 43

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 44

- 1 2 3 Van Allen, p. 46

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 34

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 36

- ↑ Crowder, p. 155

- ↑ Crowder, p. 46–48

- 1 2 Van Allen, p. 37

- ↑ Van Allen, pp. 37–38

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 33

- ↑ "The Raggedy Man and Little Orphant Annie". Indiana University. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ↑ Crowder, p. 38

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 45

- ↑ Crowder, p. 52

- ↑ Crowder, p. 53

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 51

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 55

- 1 2 Van Allen, p. 56

- ↑ Crowder, p. 56

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 58

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 59

- ↑ Crowder, p. 56–57

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 61

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 65

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 66

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 69

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 70

- ↑ Crowder, p. 64

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 71

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 75

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 77

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 86

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 89

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 91

- ↑ Crowder, p. 75

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 93

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 95

- ↑ Crowder, p. 76

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 96

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 97

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 102

- ↑ Crowder, p.79

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 105

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 106

- ↑ Crowder, p. 82

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 112

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 115

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 116

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 117

- ↑ Crowder, p. 83

- 1 2 Van Allen, p. 118

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 122

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 125

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 128

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 132

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 136

- ↑ Hamlin, Garland (February 1894). Real Conversations: A Dialogue Between James Whitcomb Riley and Hamlin Garland. McClure's Magazine. pp. 2–3.

- 1 2 Van Allen, p. 137

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 158

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 48

- 1 2 Van Allen, p. 139

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 151

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 148

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 146

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 154

- ↑ Crowder, p. 95

- ↑ Crowder, p. 93

- ↑ Crowder, p. 94

- ↑ Crowder, p. 104

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 157

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 165

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 166

- ↑ Crowder, p. 100

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 160

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 162

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 163

- ↑ Crowder, p. 111

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 174

- ↑ Crowder, p. 105

- ↑ Crowder, p. 112

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 176

- ↑ Van Allen, pp. 178–179

- ↑ Crowder, p. 119

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 180–183

- ↑ Crowder, p. 106

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 184

- ↑ Crowder, p. 107

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 185

- 1 2 Van Allen, p. 213

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 188

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 192

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 193

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 194

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 196

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 197

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 199

- ↑ Van Allen, pp. 204–205

- ↑ Crowder, pp. 108–110

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 301

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 207

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 208

- ↑ Crowder, p. 121

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 202

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 203

- 1 2 Crowder, p. 149

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 209

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 210

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 211

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 212

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 214

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 217

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 216

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 224

- ↑ Crowder, p. 133

- 1 2 Van Allen, p. 225

- ↑ Crowder, p. 132

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 218

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 219

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 220

- 1 2 Van Allen, p. 221

- ↑ Crowder, p. 123

- ↑ Crowder, p. 124

- ↑ Crowder, p. 130

- ↑ Crowder, p. 134

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 226

- ↑ Crowder, p. 137

- ↑ Crowder, p. 138

- ↑ Crowder, p. 139

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 227

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 229

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 230

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 231

- ↑ Crowder, p. 140

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 232

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 237

- ↑ Crowder, p. 148

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 238

- 1 2 Van Allen, p. 239

- ↑ Crowder, p. 151

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 228

- 1 2 3 Van Allen, p. 240

- ↑ Crowder, p. 153

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 243

- ↑ Van Allen p. 244

- 1 2 Van Allen, p. 245

- ↑ Vann Allen, p. 248

- 1 2 Van Allen, p. 251

- ↑ Crowder, p. 163

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 246

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 247

- ↑ Crowder, p. 145

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 236

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 250

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 249

- ↑ Crowder, p. 179

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 253

- ↑ Crowder, p. 203

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 254

- ↑ Crowder, p. 187

- 1 2 3 Van Allen, p. 242

- ↑ Crowder, p. 189

- ↑ Crowder, pp. 206, 210, 224

- ↑ Crowder, p. 234

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 255

- 1 2 Van Allen, p. 256

- ↑ Crowder, p. 228

- ↑ Crowder, p. 233

- ↑ Crowder, p. 232

- 1 2 Van Allen, p. 257

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 258

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 259

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 261

- ↑ Crowder, p. 252

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 262

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 1

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 2

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 3

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 4

- ↑ "Camp Riley". Riley Kids.org. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 272

- ↑ http://www.nccsc.k12.in.us/index.php/schoolstop/elementarytop/rileymoodletop.html

- ↑ "Google Maps".

- ↑ "Stamp Series". United States Postal Service. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 274

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 269

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 270

- ↑ Crowder, p. 255

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Galens, David, ed. (2003). Poetry Criticism. 48. Gale Cengage. pp. 210–212.

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 235

- ↑ Van Allen, p. 234

- 1 2 3 4 Greasley, p. 434

References

- Bodenhamer, David J.; Robert Graham Barrows; David Gordon Vanderstel (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-31222-1.

- Cottman, George S. "Some Reminiscences of James Whitcomb Riley," Indiana Magazine of History, vol. 14, no. 2 (June 1918), pp. 99–107. In JSTOR

- Crowder, Richard (1957). Those Innocent Years. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company.

- Greasley, Philip A. (2001). Dictionary of Midwestern Literatures. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33609-5.

- Van Allen, Elizabeth J. (1999). James Whitcomb Riley: a life. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33591-4.

External links

- James Whitcomb Riley Museum Home – where Riley lived for most of his adult life, on a cobblestone street in the Lockerbie neighborhood near downtown Indianapolis

- Guide to the Riley Collections at the Lilly Library – Indiana University, Bloomington.

- Indiana State Library Treasures—digital collection featuring materials related to Riley from the Indiana State Library.

- Riley Children's Foundation – supporting Riley Hospital for Children, Camp Riley for Youth with Physical Disabilities and the James Whitcomb Riley Museum Home

- The James Whitcomb Riley Digital Collection – IUPUI University Library

- Cambridge History of English and American Literature vol. 17: Later National poets

- Songs O' Cheer – collection of humorous poems (with art) from the book published in 1883.

- James Whitcomb Riley Recordings – 17 recordings from 1912 of James Whitcomb Riley reading his poems

- Still Another Look at Jim Riley, biographical essay by poet Jared Carter.

- Works by James Whitcomb Riley at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about James Whitcomb Riley at Internet Archive

- Works by James Whitcomb Riley at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- James Whitcomb Riley at Find a Grave