James Burnham

James Burnham (November 22, 1905 – July 28, 1987) was an American philosopher and political theorist. A radical activist in the 1930s and an important factional leader of the American Trotskyist movement, in later years Burnham left Marxism and turned to the political Right, serving as a public intellectual of the American conservative movement, and producing the work for which he is best known, The Managerial Revolution, published in 1941. Burnham is also remembered as a regular contributor to America's leading conservative publication, National Review, on a variety of topics.

Biography

Early life

Born in Chicago, Illinois on November 22, 1905,[1] James Burnham was the son of Claude George Burnham, an English immigrant and executive with the Burlington Railroad.[2] James was raised as a Roman Catholic but rejected Catholicism as a college student, professing atheism for much of his life (although returning to the church shortly before his death).[3] He graduated at the top of his class at Princeton University before attending Balliol College, Oxford University, where his professors included J.R.R. Tolkien and Martin D'Arcy. In 1929, he became a professor of philosophy at New York University.[4]

Radical politics

| Part of a series on |

| Communism |

|---|

|

|

Concepts

|

|

Internationals |

|

Related topics |

|

|

In 1933, along with Sidney Hook, Burnham helped to organize the American Workers Party led by the Dutch-born pacifist minister A.J. Muste.[5] Burnham supported the 1934 merger with the Communist League of America which formed the U.S. Workers Party. In 1935 he allied with the Trotskyist wing of that party and favored fusion with the Socialist Party of America. During this period, he became a friend to Leon Trotsky. Writing for The Partisan Review, Burnham was also an important influence on writers such as Dwight MacDonald and Philip Rahv.[6] However, Burnham's engagement with Trotskyism was short-lived: from 1937 a number of disagreements came to the fore.

In 1937, the Trotskyists were expelled from the Socialist Party, an action which led to the formation of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) at the end of the year. Inside the SWP, Burnham allied with Max Shachtman in a faction fight over the position of the SWP's majority faction, led by James P. Cannon and backed by Leon Trotsky, defending the Soviet Union as a degenerated workers state against the incursions of imperialism. Shachtman and Burnham, especially after witnessing the Nazi-Soviet pact of 1939 and the invasions of Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia by Joseph Stalin's regime, as well as the Soviet invasion of Finland in November 1939, came to contend that the USSR was a new form of imperialistic class society and was thus not worthy of even critical support from the socialist movement.

In February 1940 he wrote Science and Style: A Reply to Comrade Trotsky, in which he broke with dialectical materialism. In this text he responds to Trotsky's request to draw his attention to "those works which should supplant the system of dialectic materialism for the proletariat" by referring to Principia Mathematica by Russell and Whitehead and "the scientists, mathematicians and logicians now cooperating in the new Encyclopedia of Unified Science".[7]

After a protracted discussion inside the SWP, in which the factions argued their case in a series of heated internal discussion bulletins, the special 3rd National Convention of the organization in early April 1940 decided the question in favor of the Cannon majority by a vote of 55–31.[8] Even though the majority sought to avoid a split by offering to continue the debate and to allow proportional representation of the minority on the party's governing National Committee, Shachtman, Burnham, and their supporters resigned from the SWP to launch their own organization, again called the Workers Party.

This break also marked the end of Burnham's participation in the radical movement, however. On May 21, 1940, he addressed a letter to the National Committee of the Workers Party resigning from the organization. In it he made it clear the distance he had moved away from Marxism:

I reject, as you know, the "philosophy of Marxism," dialectical materialism....

The general Marxian theory of "universal history," to the extent that it has any empirical content, seems to me disproved by modern historical and anthropological investigation.

Marxian economics seems to me for the most part either false or obsolete or meaningless in application to contemporary economic phenomena. Those aspects of Marxian economics which retain validity do not seem to me to justify the theoretical structure of the economics.

Not only do I believe it meaningless to say that "socialism is inevitable" and false that socialism is "the only alternative to capitalism"; I consider that on the basis of the evidence now available to us a new form of exploitive society (which I call "managerial society") is not only possible but is a more probable outcome of the present than socialism....

On no ideological, theoretic or political ground, then, can I recognize, or do I feel, any bond or allegiance to the Workers Party (or to any other Marxist party). That is simply the case, and I can no longer pretend about it, either to myself or to others.[9][10]

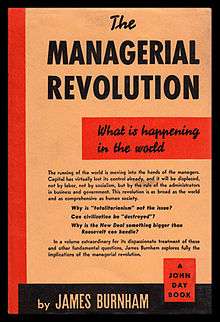

In 1941, Burnham wrote a book analyzing the development of economics and society as he saw it, called The Managerial Revolution: What is Happening in the World. The book was included in Life Magazine's list of the 100 outstanding books of 1924–1944.[11]

Post radical years

During World War II, Burnham "took a leave" from NYU and went on to work for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency. Recommended by George F. Kennan, Burnham was invited to lead the "Political and Psychological Warfare" division of the Office of Policy Coordination, a semi-autonomous part of the agency.[12]

After the war, during the period which came to be known as the "Cold War," he called for an aggressive strategy to undermine the Soviet Union's power. A contributor to The Freeman in the early 1950s, he considered the magazine to be too focused on economic issues, as a matter of emphasis, and it presented a wide range of opinion on the question of how to react to the Soviet threat. In The Struggle for the World (1947), he called for common citizenship between the United States and Great Britain and the English dominions, as well as a "World Federation" to fight communism. Burnham thought in terms of a unipolar world, instead of a balance of power:

"A World Federation initiated and led by the United States would be, we have recognized, a World Empire. In this imperial federation, the United States, with a monopoly of atomic weapons, would hold a preponderance of decisive material power over all the rest of the world. In world politics, that is to say, there would not be a balance of power."[13]

In 1955, he helped William F. Buckley, Jr. to found National Review magazine, which from the start took positions in foreign policy consistent with Burnham's own. Burnham became a lifelong contributor to the journal, and Buckley referred to him as “the number one intellectual influence on National Review since the day of its founding.”[12] His approach to foreign policy has caused some to regard him as the first "neoconservative," although Burnham's ideas have been an important influence on both the paleoconservative and neoconservative factions of the American Right.[14]

In 1983, President Ronald Reagan awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

In early November 1978 he suffered a stroke which affected his health and short-term memory.[15] He died of kidney and liver cancer[16] at home in Kent, Connecticut on July 28, 1987.[17] He was buried in Kent on August 1, 1987.[18]

Ideas

The Managerial Revolution

Burnham's seminal work, The Managerial Revolution, attempted to theorize about the future of world capitalism based upon observations of its development in the interwar period. Burnham argued three possible futures for capitalism: (1) that capitalism was a permanent form of social and economic organization and that it would be continued for a protracted period of time; (2) that capitalism was a temporary form of organization destined by its nature to collapse and be replaced by socialism; (3) that capitalism was a temporary form of organization currently being transformed into some non-socialist future form of society.[19] Burnham argued that since capitalism had a more or less definite beginning, which he dated to approximately the 14th Century, it could not be regarded as an immutable and permanent form.[20] Moreover, Burnham observed that in the last years of previous forms of economic organization, such as those of Ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, mass unemployment was "a symptom that a given type of social organization is just about finished."[21] The worldwide mass unemployment of the depression era was, for Burnham, indicative that capitalism was itself "not going to continue much longer."[21]

Burnham looked around the world for indications of the new form of society which was emerging to replace historic capitalism and saw certain commonalities between the economic formations of Nazi Germany, Stalinist Russia, and America under Franklin D. Roosevelt and his "New Deal." Burnham argued that over a comparatively short period, which he dated from the first world war, a new society had emerged in which a "social group or class" which Burnham called "managers" had engaged in a "drive for social dominance, for power and privilege, for the position of ruling class."[22] For at least a decade previous to Burnham's book, the idea of a "separation of ownership and control" of the modern corporation had been part of American economic thought, with Burnham citing The Modern Corporation and Private Property by Berle and Means as an important exposition.[23] Burnham expanded upon this concept, arguing that whether ownership was corporate and private or statist and governmental, the essential demarcation between the ruling elite (executives and managers on the one hand, bureaucrats and functionaries on the other) and the mass of society was not ownership so much as it was control of the means of production.

Burnham emphasized that "New Dealism," as he called it, "is not, let me repeat, a developed, systematized managerial ideology." Still, this ideology had contributed to American capitalism's moving in a "managerial direction":

In its own more confused, less advanced way, New Dealism too has spread abroad the stress on the state as against the individual, planning as against private enterprise, jobs (even if relief jobs) against opportunities, security against initiative, "human rights" against "property rights." There can be no doubt that the psychological effect of New Dealism has been what the capitalists say it has been: to undermine public confidence in capitalist ideas and rights and institutions. Its most distinctive features help to prepare the minds of the masses for the acceptance of the managerial social structure.[24]

In June 1941, a hostile review of The Managerial Revolution by Socialist Workers Party loyalist Joseph Hansen in the SWP's theoretical magazine accused Burnham of having lifted the central ideas of his book "without acknowledging the source" from the Italian Bruno Rizzi and his 1939 book La Bureaucratisation du Monde.[25] Despite certain similarities, there is no evidence Burnham knew of this book beyond Leon Trotsky's brief references to it. Burnham was likely influenced by Rizzi negatively and secondhand, as Trotsky mentioned Rizzi's ideas in his debates with Burnham.[26] Burnham's arguments stemmed partly from the idea of bureaucratic collectivism first introduced to Trotskyism by Yvan Craipeau, but in Burnham's case from a conservative Machiavellian rather than a Marxist viewpoint. This important philosophical difference, explored in greater detail in The Machiavellians, made Burnham's theory distinct from the similar concepts that had been developing in Trotskyist circles in the 1930s.

Later writings

In a later book, The Machiavellians, he argued and developed his theory that the emerging new élite would better serve its own interests if it retained some democratic trappings—political opposition, a free press, and a controlled "circulation of the élites."

His 1964 book Suicide of the West became a classic text for the post-war conservative movement in U.S. politics, which best expressed Burnham's new interest in traditional moral values, classical liberal economics and anti-communism. In Suicide, he defined liberalism as a "syndrome" rendering liberals ridden with guilt and internal contradictions. The works of James Burnham greatly influenced paleoconservative author Samuel T. Francis, who wrote two books about Burnham, and based his political theories upon the "managerial revolution" and the resulting managerial state.

Burnham's ideas, in both The Managerial Revolution and in The Machiavellians and in articles which were published in Partisan Review, and elsewhere were thoroughly criticised by George Orwell in his 1946 essay Second Thoughts on James Burnham (first published in Polemic (London).

See also

Works

- Introduction to philosophical analysis (with Philip Wheelwright) New York, Henry Holt and Company 1932.

- War and the workers. New York: Workers Party of the United States, 1935 (as John West) alternate link

- Why did they "confess"? a study of the Radek-Piatakov trial. New York: Pioneer Publishers, 1937 alternate link

- The People's Front: The New Betrayal. New York: Pioneer Publishers, 1937. alternate link.

- How to Fight War: Isolation, Collective Security, Relentless Class Struggle? New York: Socialist Workers Party and Young Peoples Socialist League (4th Internationalists), 1938.

- Let the people vote on war! New York: Pioneer Publishers, 1939?

- The Managerial Revolution: What is Happening in the World. New York: John Day Co., 1941.

- In defense of Marxism (against the petty-bourgeois opposition)'' (with Leon Trotsky, Joseph Hansen and William Warde) New York: Pioneer Publishers, 1942

- The Machiavellians: Defenders of Freedom New York: John Day Co., 1943 ISBN 0-89526-785-3

- The struggle for the world New York: John Day Co., 1947

- The case for De Gaulle; a dialogue between André Malraux and James Burnham. New York: Random House, 1948

- The Coming Defeat of Communism New York: John Day Co., 1949

- Why does a country go communist? [An address delivered at the Indian Congress for Cultural Freedom on March 31, 1951] Bombay, Democratic Research Service, 1951

- The case against Adlai Stevenson New York, N.Y.: American Mercury, 1952

- Containment or liberation? An inquiry into the aims of United States foreign policy. New York: John Day Co., 1953

- The Web of Subversion: Underground Networks New York: John Day Co., 1954

- Congress and the American Tradition Chicago, H. Regnery Co., 1959 ISBN 0-7658-0997-4

- Bear and dragon; what is the relation between Moscow and Peking? New York, National Review, in cooperation with the American-Asian Exchange, 1960

- Does ADA run the New Frontier? New York, National Review, 1963

- Suicide of the West: An Essay on the Meaning and Destiny of Liberalism New York: John Day Co., 1964 ISBN 0-89526-822-1

- The War We Are In: The Last Decade and the Next New Rochelle, NY, Arlington House 1967

References

- ↑ Manfred Overesch, Friedrich Wilhelm Saal (1986). Chronik deutscher Zeitgeschichte: Politik, Wirtschaft, Kultur, Volume 3, Part 2. Droste. p. 791. ISBN 3-7700-0719-0.

- ↑ "Sempa | James Burnham (I)". Unc.edu. 2000-12-03. Retrieved 2012-11-25.

- ↑ Priscilla Buckley, "James Burnham 1905–1987." National Review, July 11, 1987, p. 35.

- ↑ Roger Kimball, "The Power of James Burnham," The New Criterion, Sept. 2002.

- ↑ John Patrick Diggins, Up From Communism, 1975, Columbia Univ. Press, pp. 169–70, and "The Cerebral Communist: James Burnham," pp.160–201.

- ↑ Diggins, Up From Communism, p.180.

- ↑ Burhham J. (1940) Science and Style A Reply to Comrade Trotsky, in In Defence of Marxism by Leon Trotsky, London 1966, pp.232-256.

- ↑ James P. Cannon, "The Convention of the Socialist Workers Party," The Fourth International, v. 1, no. 1 (May 1940), p. 16.

- ↑ James Burnham, "Burnham's Letter of Resignation," The Fourth International, v. 1, no. 4 (August 1940), pp. 106–07.

- ↑ "James Burnham: Letter of Resignation (1940)" on Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ↑ Canby, Henry Seidel. "The 100 Outstanding Books of 1924–1944". Life Magazine, 14 August 1944. Chosen in collaboration with the magazine's editors.

- 1 2 Roger Kimball, "The Power of James Burnham," The New Criterion, Sept. 2002.

- ↑ James Burnham, The Struggle for the World (Toronto: Longmans, 1947), 190, 210.

- ↑ Binoy Kampmark, "The First Neo-conservative: James Burnham and the Origins of a Movement," Review of International Studies, 12 Oct. 2010.

- ↑ Kupferberg, Feiwel (2002). The rise and fall of the German Democratic Republic. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. p. 60. ISBN 0-7658-0122-1.

- ↑ Hart, Jeffrey D. (2005). The making of the American conservative mind: National review and its times. Wilmington, Del.: ISI Books. p. 255. ISBN 1-932236-81-3.

- ↑ Francis, Samuel T. (1994). Beautiful Losers: Essays on the Failure of American Conservatism. Univ of Missouri Pr. p. 129. ISBN 0-8262-0976-9.

- ↑ Smant, Kevin J. (1992). How great the triumph: James Burnham, anticommunism, and the conservative movement. Lanham: University Press of America. p. 152. ISBN 0-8191-8464-0.

- ↑ James Burnham, The Managerial Revolution: What is Happening in the World. New York: John Day Co., 1941; p. 29.

- ↑ Burnham, The Managerial Revolution, p. 30.

- 1 2 Burnham, The Managerial Revolution, p. 31.

- ↑ Burnham, The Managerial Revolution, p. 71.

- ↑ Burnham, The Managerial Revolution, p. 88.

- ↑ Burnham, The Managerial Revolution, pp. 201–202.

- ↑ Joseph Hansen, "Burnham's 'Managerial Revolution,'" The Fourth International, v. 2, no. 5 (June 1941), p. 157.

- ↑ The Bureaucratization of the World: The USSR: Bureaucratic Collectivism – Bruno Rizzi, Adam Westoby – Google Books. Books.google.com. 1985. ISBN 9780422786003. Retrieved 2012-11-25.

Further reading

- John P. Diggins, Up From Communism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1975.

- Samuel Francis, Power and History, The Political Thought of James Burnham. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1984.

- Samuel Francis, James Burnham: Thinkers of Our Time. London: Claridge Press, 1999.

- Grant Havers, "James Burnham's Elite Theory and the Postwar American Right," Telos 154 (Spring 2011): 29–50.

- Benjamin Guy Hoffman, The Political Thought of James Burnham. PhD dissertation. University of Michigan, 1969.

- Daniel Kelly, James Burnham and the Struggle for the World: A Life. Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2002.

- C. Wright Mills and Hans Gerth, "A Marx for the Managers", 1942. Reprinted in Power, Politics, and People: The Collected Essays of C. Wright Mills edited by Irving Horowitz. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

- George Orwell, "Second Thoughts on James Burnham," Polemic, No. 3, May 1946.

- Paul Sweezy, "The Illusion of the 'Managerial Revolution,'" Science & Society, vol. 6, no. 1 (Winter 1942), pp. 1–23. In JSTOR.

External links

-

Quotations related to James Burnham at Wikiquote

Quotations related to James Burnham at Wikiquote - James Burnham Internet Archive at Marxists Internet Archive

- Register of the James Burnham Papers, 1928-1983, the Online Archive of California (OAC) initiative of the California Digital Library

- Obituary of James Burnham, National Review, September 11, 1987

- James Burnham, The New Class, And The Nation-State, by Samuel T. Francis,VDARE.com, August 23, 2001

- Lenin's heir. By Victor Serge. At Victor Serge Archive (Marxists Internet Archive)

- Appearances on C-SPAN