Ivanhoe

Title page of 1st edition (1820). | |

| Author | Sir Walter Scott |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Series | Waverley Novels |

| Genre | Historical novel, chivalric romance |

| Publisher | A. Constable |

Publication date | 1820 |

| Pages | 1,004, in three volumes |

| 823.7 | |

| Preceded by | Rob Roy |

| Followed by | Kenilworth |

Ivanhoe /ˈaɪvənˌhoʊ/ is a historical novel by Sir Walter Scott, first published in 1820 in three volumes and subtitled A Romance. Ivanhoe, set in 12th century England, has been credited for increasing interest in romance and medievalism; John Henry Newman claimed Scott "had first turned men's minds in the direction of the Middle Ages", while Carlyle and Ruskin made similar assertions of Scott's overwhelming influence over the revival, based primarily on the publication of this novel.[1]

Plot introduction

Ivanhoe is the story of one of the remaining Saxon noble families at a time when the nobility in England was overwhelmingly Norman. It follows the Saxon protagonist, Sir Wilfred of Ivanhoe, who is out of favour with his father for his allegiance to the Norman king Richard the Lionheart. The story is set in 1194, after the failure of the Third Crusade, when many of the Crusaders were still returning to their homes in Europe. King Richard, who had been captured by Leopold of Austria on his return journey to England, was believed to still be in captivity.

The legendary Robin Hood, initially under the name of Locksley, is also a character in the story, as are his "merry men". The character that Scott gave to Robin Hood in Ivanhoe helped shape the modern notion of this figure as a cheery noble outlaw.

Other major characters include Ivanhoe's intractable father, Cedric, one of the few remaining Saxon lords; various Knights Templar, most notable of whom is Brian de Bois-Guilbert, Ivanhoe's main rival; a number of clergymen; the loyal serfs: Gurth the swineherd and the jester Wamba, whose observations punctuate much of the action; and the Jewish moneylender, Isaac of York, who is equally passionate about his people and his beautiful daughter, Rebecca. The book was written and published during a period of increasing struggle for the emancipation of the Jews in England, and there are frequent references to injustices against them.

Plot summary

Opening

Protagonist Wilfred of Ivanhoe is disinherited by his father Cedric of Rotherwood for supporting the Norman King Richard and for falling in love with the Lady Rowena, Cedric's ward and a descendant of the Saxon Kings of England, after Cedric planned to marry her to the powerful Lord Athelstane, a pretender to the Crown of England through his descent from the last Saxon King, Harold Godwinson. Ivanhoe accompanies King Richard on the Crusades, where he is said to have played a notable role in the Siege of Acre; and tends to Louis of Thuringia, who suffers from malaria.

The book opens with a scene of Norman knights and prelates seeking the hospitality of Cedric. They are guided there by a pilgrim, known at that time as a palmer, (one who carried blessed palms leaves such as those that were scattered at the feet of Jesus Christ by residents of Jerusalem when he entered seated on an donkey's colt on the Sunday before his arrest, trial and crucifixion; hence the name Palm Sunday). Also returning from the Holy Land that same night, Isaac of York, a Jewish moneylender, seeks refuge at Rotherwood. Following the night's meal, the palmer observes one of the Normans, the Templar Brian de Bois-Guilbert, issue orders to his Saracen soldiers to capture Isaac.

The palmer then assists in Isaac's escape from Rotherwood, with the additional aid of the swineherd Gurth.

Isaac of York offers to repay his debt to the palmer with a suit of armour and a war horse to participate in the tournament at Ashby-de-la-Zouch, on his inference that the palmer was secretly a knight. The palmer is taken by surprise; but accepts the offer.

The tournament

The story then moves to the scene of the tournament, presided over by Prince John. Other characters in attendance are Cedric, Athelstane, Lady Rowena, Isaac of York, his daughter Rebecca, Robin of Locksley and his men, Prince John's advisor Waldemar Fitzurse, and numerous Norman knights.

On the first day of the tournament, a bout of individual jousting, a mysterious knight, identifying himself only as "Desdichado" (described in the book as Spanish for the "Disinherited", though actually meaning "Unfortunate"), defeats some of the best Norman competitors, including Bois-Guilbert, Maurice de Bracy (a leader of a group of "Free Companions"), and the baron Reginald Front-de-Boeuf. The masked knight declines to reveal himself despite Prince John's request, but is nevertheless declared the champion of the day and is permitted to choose the Queen of the Tournament. He bestows this honour upon the Lady Rowena.

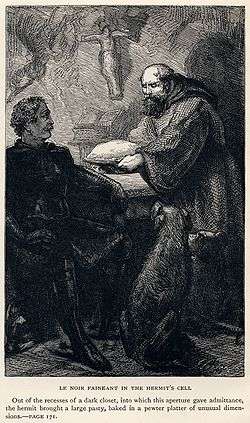

On the second day, at a melee, Desdichado is the leader of one party, opposed by his former adversaries. Desdichado's side is soon hard pressed and he himself beset by multiple foes, until rescued by a knight nicknamed 'Le Noir Faineant' ("the Black Sluggard"), who thereafter departs in secret. When forced to unmask himself to receive his coronet (the sign of championship), Desdichado is identified as Wilfred of Ivanhoe, returned from the Crusades. This causes much consternation to Prince John and his court who now fear the imminent return of King Richard.

Because he is severely wounded in the competition, Ivanhoe is taken into the care of Rebecca, the daughter of Isaac, who is a skilled healer. She convinces her father to take him with them to York, where he can be best treated. The story then glosses the conclusion of the tournament including feats of archery by Locksley.

Capture and rescue

In the forests between Ashby and York, the Lady Rowena, Cedric and Athelstane acquire Isaac, Rebecca and the wounded Ivanhoe, who have been abandoned by their servants for fear of bandits. En route, the party is captured by de Bracy and his companions and taken to Torquilstone, the castle of Front-de-Boeuf. The swineherd Gurth, who had served Ivanhoe as squire at the tournament and who was recaptured by Cedric when Ivanhoe was identified, manages to escape.

The Black Knight, having taken refuge for the night in the hut of a local friar, the Holy Clerk of Copmanhurst, volunteers his assistance on learning about the captives from Robin of Locksley. They then besiege the Castle of Torquilstone with Robin's own men, including the friar and assorted Saxon yeomen. At Torquilstone, de Bracy expresses his love for the Lady Rowena, but is refused. Brian de Bois-Guilbert tries to seduce Rebecca, and is rebuffed. Front-de-Boeuf tries to wring a hefty ransom from Isaac of York; but Isaac refuses to pay unless his daughter is freed.

When the besiegers deliver a note to yield up the captives, their Norman captors demand a priest to administer the Final Sacrament to Cedric; whereupon Cedric's jester Wamba slips in disguised as a priest, and takes the place of Cedric, who then escapes and brings important information to the besiegers on the strength of the garrison and its layout. The besiegers then storm the castle. The castle is set aflame during the assault by Ulrica, the daughter of the original lord of the castle, Lord Torquilstone, as revenge for her father's death. Front-de-Boeuf is killed in the fire while de Bracy surrenders to the Black Knight, who identifies himself as King Richard and releases de Bracy. Bois-Guilbert escapes with Rebecca while Isaac is rescued by the Clerk of Copmanhurst. The Lady Rowena is saved by Cedric, while the still-wounded Ivanhoe is rescued from the burning castle by King Richard. In the fighting, Athelstane is wounded and presumed dead while attempting to rescue Rebecca, whom he mistakes for Rowena.

Rebecca's trial and Ivanhoe's reconciliation

Following the battle, Locksley plays host to King Richard. Word is also conveyed by de Bracy to Prince John of the King's return and the fall of Torquilstone. In the meantime, Bois-Guilbert rushes with his captive to the nearest Templar Preceptory, where Lucas de Beaumanoir, the Grand-Master of the Templars, takes umbrage at Bois-Guilbert's infatuation, and subjects Rebecca to a trial for witchcraft. At Bois-Guilbert's secret request, she claims the right to trial by combat; and Bois-Guilbert, who had hoped for the position, is devastated when the Grand-Master orders him to fight against Rebecca's champion. Rebecca then writes to her father to procure a champion for her. Cedric organises Athelstane's funeral at Coningsburgh, in the midst of which the Black Knight arrives with a companion. Cedric, who had not been present at Locksley's carousal, is ill-disposed towards the knight upon learning his true identity; but Richard calms Cedric and reconciles him with his son. During this conversation, Athelstane emerges – not dead, but laid in his coffin alive by monks desirous of the funeral money. Over Cedric's renewed protests, Athelstane pledges his homage to the Norman King Richard and urges Cedric to marry Rowena to Ivanhoe; to which Cedric finally agrees.

Soon after this reconciliation, Ivanhoe receives word from Isaac beseeching him to fight on Rebecca's behalf. Accordingly, Ivanhoe overcomes Bois-Guilbert but does not kill him, and the Templar dies of internal causes which is pronounced by the Grand Master as the judgement of God and proof of Rebecca's innocence.

Fearing further persecution, Rebecca and her father leave England for Granada. Before leaving, Rebecca comes to bid Rowena a fond farewell. Finally, Ivanhoe and Rowena marry and live a long and happy life together, though the final paragraphs of the book note that Ivanhoe's military service ended with the death of King Richard.

Characters

Wilfred of Ivanhoe, the titular character, is a knight and son of Cedric the Saxon. Ivanhoe, though of a more noble lineage than some of the other characters, represents a middling individual in the medieval class system who is not exceptionally outstanding in his abilities, as is expected of other quasi-historical fictional characters, such as the Greek heroes. Critic György Lukács points to middling main characters like Ivanhoe in Sir Walter Scott's other novels as one of the primary reasons Scott's historical novels depart from previous historical works, and better explore social and cultural history.[2]

Other characters

- Rebecca – a Jewish healer, young daughter of Isaac of York

- Lady Rowena – a Saxon lady under the protection of Cedric of Rotherwood

- Prince John – brother of King Richard

- The Black Knight or The Sluggish Knight – King Richard, incognito

- Locksley – Robin Hood, an English yeoman

- The Hermit or Clerk of Copmanhurst – Friar Tuck

- Sir Brian de Bois-Guilbert – the leader of the Knights Templar; a friend of Prince John

- Isaac of York – the father of Rebecca; a Jewish merchant and money-lender

- Prior Aymer – Prior of Jorvaulx Abbey; friendly to Prince John

- Reginald Front-de-Boeuf – a local baron who was given Ivanhoe's estate by Prince John

- Cedric the Saxon/Cedric of Rotherwood – Ivanhoe's father, a Saxon noble

- Lucas de Beaumanoir – Grand Master of the Knights Templar

- Conrade de Montfichet – a Templar knight

- Maurice de Bracy – Captain of the Free Companions, a band of mercenaries. He introduces the word "freelance": "I offered Richard the service of my Free Lances, and he refused them... thanks to the bustling times, a man of action will always find employment".

- Waldemar Fitzurse – Prince John's loyal minion; his name tied to Reginald Fitzurse, one of the killers of Thomas Becket

- Athelstane of Coningsburgh – last of the Saxon royal line

- Albert de Malvoisin – Preceptor of Templestowe

- Philip de Malvoisin – a local baron, the brother of Albert

- Gurth – Cedric the Saxon's swineherd

- Wamba – Cedric the Saxon's loyal jester

- Ulrica – An elderly woman locked in the castle of Front-de-Boeuf, where she has been imprisoned for much of her life. The castle was captured from her father by Front-de-Boeuf when she herself was young.

- Kirjath Jairam of Leicester – a rich Jew

- Hubert - winner of the first round of the archery contest

- Alan-a-Dale - member of Locksley's band

Style

Critics of the novel have treated it as a romance intended mainly to entertain boys.[3] Ivanhoe maintains many of the elements of the Romance genre, including the quest, a chivalric setting, and the overthrowing of a corrupt social order in order to bring on a time of happiness.[4] Other critics assert that the novel creates a realistic and vibrant story, idealising neither the past nor its main character.[3][4]

Themes

Scott treats themes similar to those of some of his earlier novels, like Rob Roy and The Heart of Midlothian, examining the conflict between heroic ideals and modern society. In the latter novels, industrial society becomes the centre of this conflict as the backward Scottish nationalists and the "advanced" English have to arise from chaos to create unity. Similarly, the Normans in Ivanhoe, who represent a more sophisticated culture, and the Saxons, who are poor, disenfranchised, and resentful of Norman rule, band together and begin to mould themselves into one people. The conflict between the Saxons and Normans focuses on the losses both groups must experience before they can be reconciled and thus forge a united England. The particular loss is in the extremes of their own cultural values, which must be disavowed in order for the society to function. For the Saxons, this value is the final admission of the hopelessness of the Saxon cause. The Normans must learn to overcome the materialism and violence in their own codes of chivalry. Ivanhoe and Richard represent the hope of reconciliation for a unified future.[3]

Allusions to real history and geography

The location of the novel is centred upon southern Yorkshire and northern Nottinghamshire in England. Castles mentioned within the story include Ashby de la Zouch Castle (now a ruin in the care of English Heritage), York (though the mention of Clifford's Tower, likewise an extant English Heritage property, is anachronistic, it not having been called that until later after various rebuilds) and 'Coningsburgh', which is based upon Conisbrough Castle, in the ancient town of Conisbrough near Doncaster (the castle also being a popular English Heritage site). Reference is made within the story to York Minster, where the climactic wedding takes place, and to the Bishop of Sheffield, although the Diocese of Sheffield did not exist at either the time of the novel or the time Scott wrote the novel and was not founded until 1914. Such references suggest that Robin Hood lived or travelled in the region.

Conisbrough is so dedicated to the story of Ivanhoe that many of its streets, schools, and public buildings are named after characters from the book.

Lasting influence on the Robin Hood legend

Our modern conception of Robin Hood as a cheerful, decent, patriotic rebel owes much to Ivanhoe.

"Locksley" becomes Robin Hood's title in the Scott novel, and it has been used ever since to refer to the legendary outlaw. Scott appears to have taken the name from an anonymous manuscript – written in 1600 – that employs "Locksley" as an epithet for Robin Hood. Owing to Scott's decision to make use of the manuscript, Robin Hood from Locksley has been transformed for all time into "Robin of Locksley", alias Robin Hood. (There is, incidentally, a village called Loxley in Yorkshire.)

Scott makes the 12th-century's Saxon-Norman conflict a major theme in his novel. Recent re-tellings of the story retain his emphasis. Scott also shunned the late 16th-century depiction of Robin as a dispossessed nobleman (the Earl of Huntingdon). This, however, has not prevented Scott from making an important contribution to the noble-hero strand of the legend, too, because some subsequent motion picture treatments of the Robin Hood's adventures give Robin traits that are characteristic of Ivanhoe as well. The most notable Robin Hood films are the lavish Douglas Fairbanks 1922 silent film, the 1938 triple Academy Award winning Adventures of Robin Hood with Errol Flynn as Robin (which contemporary reviewer Frank Nugent links specifically with Ivanhoe[5]), and the 1991 box-office success Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves with Kevin Costner). There is also the Mel Brooks spoof, Robin Hood: Men in Tights. In most versions of Robin Hood, both Ivanhoe and Robin, for instance, are returning Crusaders. They have quarreled with their respective fathers, they are proud to be Saxons, they display a highly evolved sense of justice, they support the rightful king even though he is of Norman-French ancestry, they are adept with weapons, and they each fall in love with a "fair maid" (Rowena and Marian, respectively).

This particular time-frame was popularised by Scott. He borrowed it from the writings of the 16th-century chronicler John Mair or a 17th-century ballad presumably to make the plot of his novel more gripping. Medieval balladeers had generally placed Robin about two centuries later in the reign of Edward I, II or III.

Robin's familiar feat of splitting his competitor's arrow in an archery contest appears for the first time in Ivanhoe.

Historical accuracy

The general political events depicted in the novel are relatively accurate; the novel tells of the period just after King Richard's imprisonment in Austria following the Crusade and of his return to England after a ransom is paid. Yet the story is also heavily fictionalised. Scott himself acknowledged that he had taken liberties with history in his "Dedicatory Epistle" to Ivanhoe. Modern readers are cautioned to understand that Scott's aim was to create a compelling novel set in a historical period, not to provide a book of history.

There has been criticism of Scott's portrayal of the bitter extent of the "enmity of Saxon and Norman, represented as persisting in the days of Richard" as "unsupported by the evidence of contemporary records that forms the basis of the story."[6] However, Scott may have intended to suggest parallels between the Norman conquest of England, about 130 years previously, and the prevailing situation in Scott's native Scotland (Scotland's union with England in 1707 – about the same length of time had elapsed before Scott's writing and the resurgence in his time of Scottish nationalism evidenced by the cult of Robert Burns, the famous poet who deliberately chose to work in Scots vernacular though he was an educated man and spoke modern English eloquently).[7] Indeed, some experts suggest that Scott deliberately used Ivanhoe to illustrate his own combination of Scottish patriotism and pro-British Unionism.[8][9]

The novel generated a new name in English – Cedric. The original Saxon name had been Cerdic but Sir Walter misspelled it – an example of metathesis. "It is not a name but a misspelling," said satirist H. H. Munro.

Wamba (disguised as a monk) says, "I am a poor brother of the Order of St Francis." However, St. Francis began his preaching in 1209, which is ten years after the death of Richard I.

In 1194 England, it would have been unlikely for Rebecca to face the threat of being burned at the stake on charges of witchcraft. It is thought that it was shortly afterwards, from the 1250s, that the Church began to undertake the finding and punishment of witches and death did not become the usual penalty until the 15th century. Even then, the form of execution used for witches in England (unlike Scotland and Continental Europe) was hanging, burning being reserved for those also convicted of treason. There are various minor errors e.g. the description of the tournament at Ashby owes more to the 14th century, and most of the coins mentioned by Scott are exotic.

"For a [Scottish] writer whose early novels [all set in Scotland] were prized for their historical accuracy, Scott was remarkably loose with the facts when he wrote Ivanhoe... But it is crucial to remember that Ivanhoe, unlike the Waverly books, is entirely a romance. It is meant to please, not to instruct, and is more an act of imagination than one of research. Despite this fancifulness, however, Ivanhoe does make some prescient historical points. The novel is occasionally quite critical of King Richard, who seems to love adventure more than he loves the well-being of his subjects. This criticism did not match the typical idealised, romantic view of Richard the Lion-Hearted that was popular when Scott wrote the book, and yet it accurately echoes the way King Richard is often judged by historians today."[10]

It has been conjectured that the character of Rebecca in the book was inspired by Rebecca Gratz, a Philadelphia teacher and philanthropist and the first Jewish female college student in America. Scott's attention had been drawn to Gratz's character by novelist Washington Irving, who was a close friend of the Gratz family. The assertion has been disputed, but it has been supported by "The Original of Rebecca in Ivanhoe", an article that appeared in The Century Magazine in 1882.

Moreover, there are some inaccuracies about English kings' history and genealogy. For instance, William II of England, cited as William Rufus (in the scene of the Joust in Ashby-de-la-Zouch), is said to have been John Lackland's grandfather, whereas he was actually his great-grand-uncle. Furthermore, while describing the violence and lack of respect of Norman barons towards women, Scott refers to Matilda's temporary vows in a nunnery, but it is unclear whether he refers to Matilda of Scotland, wife of Henry I of England (since she is defined as queen of England and daughter of the king of Scotland) or to her daughter Empress Matilda (since she is said to have been Empress of Germany and daughter and mother of kings, characteristics which can be applied only to her).

Legacy

Sequels

- The 1839 Eglinton Tournament held by the 13th Earl of Eglinton at Eglinton Castle in Ayrshire was inspired and modelled on Ivanhoe.

- In 1850, novelist William Makepeace Thackeray wrote a sequel to Ivanhoe called Rebecca and Rowena.

- Edward Eager's book Knight's Castle (1956) magically transports four children into the story of Ivanhoe.

- Simon Hawke uses the story as the basis for The Ivanhoe Gambit (1984) the first novel in his time travel adventure series TimeWars.

- Pierre Efratas wrote a sequel called Le Destin d'Ivanhoe (2003), published by Éditions Charles Corlet.

- Christopher Vogler wrote a sequel called Ravenskull (2006), published by Seven Seas Publishing.

Film, TV or theatrical adaptations

The novel has been the basis for several motion pictures:

- Ivanhoe, United States 1911, directed by Stuart Blackton

- Ivanhoe United States 1913, directed by Herbert Brenon; with King Baggot, Leah Baird, and Brenon. Filmed on location in England

- Ivanhoe, Wales 1913, directed by Leedham Bantock, filmed at Chepstow Castle

- Ivanhoe, 1952, directed by Richard Thorpe, starring Robert Taylor, Elizabeth Taylor, Joan Fontaine and George Sanders; nominated for three Oscars.

- The Ballad of the Valiant Knight Ivanhoe (Баллада о доблестном рыцаре Айвенго), USSR 1983, directed by Sergey Tarasov, with songs of Vladimir Vysotsky, starring Peteris Gaudins as Ivanhoe.

There have also been many television adaptations of the novel, including:

- 1958: A television series based on the character of Ivanhoe starring Roger Moore as Ivanhoe[11]

- 1970: A TV miniseries starring Eric Flynn as Ivanhoe.

- 1982: Ivanhoe, a television movie starring Anthony Andrews as Ivanhoe.

- 1986: Ivanhoe, a 1986 animated telemovie produced by Burbank Films in Australia.

- 1995: Young Ivanhoe, a 1995 television movie directed by Ralph L. Thomas and starring Kristen Holden-Ried as Ivanhoe, Rachel Blanchard as Rowena, Stacy Keach as Pembrooke, Margot Kidder as Lady Margarite, Nick Mancuso as Bourget, and Matthew Daniels as Tuck.

- 1997: Ivanhoe the King's Knight a televised cartoon series produced by CINAR and France Animation. General retelling of classic tale.

- 1997: Ivanhoe, a 6-part, 5-hour TV miniseries, a co-production of A&E and the BBC. It stars Steven Waddington as Ivanhoe, Ciarán Hinds as Bois-Guilbert, Susan Lynch as Rebecca, Ralph Brown as Prince John and Victoria Smurfit as Rowena.

- 1999: The Legend of Ivanhoe, a Columbia TriStar International Television production dubbed into English starring John Haverson as Ivanhoe and Rita Shaver as Rowena.

- 2005: A Channel 5 adaptation entitled Dark Knight attempted to adapt Ivanhoe for an ongoing series. Ben Pullen played Ivanhoe and Charlotte Comer played Rebecca.

Victor Sieg's dramatic cantata Ivanhoé won the Prix de Rome in 1864 and premiered in Paris the same year. An operatic adaptation of the novel by Sir Arthur Sullivan (entitled Ivanhoe) ran for over 150 consecutive performances in 1891. Other operas based on the novel have been composed by Gioachino Rossini (Ivanhoé), Thomas Sari (Ivanhoé), Bartolomeo Pisani (Rebecca), A. Castagnier (Rébecca), Otto Nicolai (Il Templario), and Heinrich Marschner (Der Templer und die Jüdin). Rossini's opera is a pasticcio (an opera in which the music for a new text is chosen from pre-existent music by one or more composers). Scott attended a performance of it and recorded in his journal, "It was an opera, and, of course, the story sadly mangled and the dialogue, in part nonsense."[12]

Other

The railway running through Ashby-de-la-Zouch has the epithet The Ivanhoe Line in reference to the book's setting in the locality.

See also

- Robin Hood

- Norman yoke

- Trysting Tree – several references are made to these trees as agreed gathering places.

- Ivanhoe, New South Wales, a small outback town in the Australian state of New South Wales, named circa 1869 by a pioneering Scottish-born settler.

- Ivanhoe, California, a small town founded in Tulare County, United States is named after the novel.

- Ivanhoe, North Carolina, a village in eastern North Carolina

- Ivanhoe, Victoria, a suburb in the Australian state of Victoria.

References

- ↑ Alice Chandler, "Sir Walter Scott and the Medieval Revival," Nineteenth-Century Fiction 19.4 (March 1965): 315–332.

- ↑ Lukas 31–38

- 1 2 3 Duncan, Joseph E. (March 1955). "The Anti-Romantic in "Ivanhoe"". Nineteenth-Century Fiction. 9 (4): 293–300. doi:10.1525/ncl.1955.9.4.99p02537. JSTOR 3044394.

- 1 2 Sroka, Kenneth M. (Autumn 1979). "The Function of Form: Ivanhoe as Romance.". Studies in English Literature (Rice). 19 (4): 645–661. JSTOR 450253.

- ↑ Nugent, Frank. "The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)" [review]. NYTimes.com/New York Times. 13 May 1939. http://movies.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=EE05E7DF173FB72CA0494CC5B67994886896

- ↑ "Ivanhoe", page 499. The Oxford Companion to English Literature, 1989

- ↑ Linklater, Andro 'Freedom and Houghmagandie', reviewing two Burns biographies. The Spectator, 24 January 2009. Retrieved August 18, 2010

- ↑ Critic Stuart Kelly, speaking at the Edinburgh International Book Festival, August 2010. The Guardian, Monday 16 August. Retrieved August 18, 2010

- ↑ Kelly, Stuart Scott-land: The Man who Invented a Nation (2010), Polygon

- ↑ SparkNotes Editors. (n.d.). SparkNote on Ivanhoe. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- ↑ Ivanhoe at epguides.com

- ↑ Dailey, Jeff S. Sir Arthur Sullivan's Grand Opera Ivanhoe and Its Musical Precursors: Adaptations of Sir Walter Scott's Novel for the Stage, 1819–1891, (2008) Edwin Mellen Press ISBN 0-7734-5068-8

Works cited

- Lukacs, Georg (1969). The Historical Novel. Penguin Books.

External links

- Ivanhoe at Project Gutenberg

- Online edition at eBooks@Adelaide

- Full text online in HTML at dustylibrary.com, by chapter

- First edition at Google Books: Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3

-

Ivanhoe public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Ivanhoe public domain audiobook at LibriVox - Ivanhoe Map

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "Ivanhoe". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "Ivanhoe". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.