Irv Docktor

Irving Seidmon Docktor (July 10, 1918 - February 14, 2008) was a prolific artist and educator best known for his work as a book and magazine illustrator in the 1950s and 1960s. His psychologically arresting and aesthetically distinctive style, featuring angular often overlapping faces executed with a moody palette, made him one of the most instantly recognizable illustrators of his era. An early work on the history of paperbacks identified Docktor and Edward Gorey as executing some of the most interesting and appealing cover designs in the field.[1]

Early life

Irving Seidmont Docktor was born and raised in Philadelphia. He graduated from Central High School in Philadelphia, and won a scholarship to the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art (now the University of the Arts) and the Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania. A weight lifter in his youth, Docktor performed in walk-on roles with Mary Binney Montgomery's ballet troupe while he was in college as a supernumerary actor, a job he obtained one day while sketching the dancers during their rehearsal. When Docktor noticed the male lead had trouble lifting his partner, he stepped in and was offered a position on the spot.[2]

Career

Illustration

After graduating from art school, Docktor entered the army and was trained in photography. During World War II, he served as an aerial photographer in a map-making unit in the Technical Intelligence Team based in Australia and the Philippines. The sketches he made during this period served as visual referents for some of his later work, such as his illustrations for a book on the Battle of Bataan.

Upon his discharge, Docktor moved first to Flushing, Queens, New York, then to Fort Lee, New Jersey, and entered the commercial art world, producing illustrations that graced the covers and interiors of many novels, children’s books and record albums. Much of his early work was for Grosset & Dunlap. His dark palette and sense of the macabre led him to paint a number of covers for mystery novels and collections of supernatural fiction. He illustrated a number of books in the "Lookouts" juvenile mystery series by Christine Noble Govan and Emmy West in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and he executed cover paintings for five science fiction novels by Robert A. Heinlein. He used his children and neighbors as models. His cover for Govan and West's Mystery of Rock City, for example, pictures his two sons and their playmates scrambling on the hillside near their house in Fort Lee.

He also did work in a brighter vein, including fashion illustrations, a luminous cover for a book on Bergdorf Goodman, and a richly illustrated book of American Folklore, which he counted among his best of his commercial work. Docktor contributed to innumerable magazines, and he painted posters for Broadway plays, including Tea and Sympathy, Long Day's Journey Into Night and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Whimsical drawings of dogs were featured in the advertising brochures and other products of the Docktor Pet Centers, a franchise founded by the artist's brother Milton. For this endeavor, Docktor expanded his range of technique to include photo collage, an approach he would occasionally use in other illustration work—in his covers for albums by The Serendipity Singers and the Dixie Double-Cats, for instance. His cover for an album by Art Tatum is an exercise in synesthesia, suggesting through strokes of color the tones of the pianist's music. Similarly, his cover for Stories of Suspense, an anthology published by Scholastic Books, evokes the mounting horror of Daphne du Maurier's story The Birds by including shadowy images of birds as a hidden visual motif.

Fine art

During this fertile period, Docktor also pursued a separate career as a fine artist. A mural commission in 1960 led him to relocate temporarily from Fort Lee, New Jersey, to New York City, and eventually to shift his emphasis from commercial illustration. By the late 1960s he had refocused on fine art, exhibiting paintings in numerous galleries and art shows in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Connecticut, garnering a number of prizes at juried shows. In additions to landscapes and highly sensuous nudes, Docktor also returned repeatedly to a sequence of paintings he called the "Heritage series," featuring juxtaposed figures and faces redolent of village life in the old world. “With technical perfection, the mystic characteristics and pathos give his art an exquisite, aesthetic quality,” remarked one reviewer in 1963.[3]

Docktor was equally devoted to education, training several generations of fine and commercial artists. He taught figure drawing, fashion illustration, calligraphy and other subjects on a part-time basis for almost 50 years at the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Arts, and for 15 years served on the full-time faculty of the High School of Art and Design in New York City.[4] He also taught occasional classes at Learning Annex. During his final years, he led art classes as a volunteer at the Senior Center in Fort Lee, New Jersey.

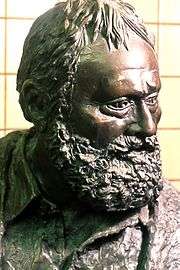

Docktor was the model for one of the seven figures in The Commuters (1984), the life-size bronze tableau by Grigory Gurevich at the entrance to the subway at Penn Station in Newark, New Jersey.

He was a member of a number of artist's unions, including the Salmagundi Club, the Pastel Society of America, the Garden State Watercolor Society, the New Jersey Watercolor Society, the Philadelphia Sketch Club, the Philadelphia Watercolor Society, the New Jersey American Artists Professional League, the Northeast Watercolor Society, the Ridgewood Art Institute, the Ringwood Manor Art Association and the Society of Illustrators.

Personal life

Docktor married Mildred Sylvia Himmelstein.[5] They lived in Fort Lee, New Jersey, in a home overlooking the Hudson River.[4] They enjoyed frequently went to museums, the theatre, the Metropolitan Opera, the Philharmonic, the American Ballet Theatre, and the New York City Ballet. During performances, Docktor was fond of sketch what he was seeing in the Playbill, and amassed a large amount of work from this activity.[4]

Docktor died February 14, 2008.[4]

Published works (partial list)

Books

- Clark Gavin, Foul, False, and Infamous: Famous Libel and Slander Cases of History (Abelard, 1950)

- Patricia Highsmith, Strangers on a Train (Harper, 1950)

- Selwyn Jepson, The Hungry Spider (Doubleday, 1950)

- Theodora DuBois, High Tension (Doubleday, 1950)

- Christiana Brand, Cat and Mouse (Knopf, 1950)

- David William Meredith [Earl Schenck Miers], The Christmas Card Murders (Knopf, 1951)

- Jessamyn West, The Witch Diggers (Harcourt, Brace, 1951)

- Carl G. Hodges, Naked Villany (Suspense Novel 3, Farrell Publishing Company, 1951)

- Ed Lacy, The Best that Ever Did It (Harper, 1955)

- Leigh Brackett, The Long Tomorrow (Doubleday, 1955)

- Lucile Iremonger, The Young Traveler in the West Indies (Dutton, 1955)

- Ruth Adams Knight, First the Lightning (Doubleday, 1955)

- Ullin W. Leavell, Mary Louise Friebele, Tracie Cushman, Paths to Follow (American Book Company, New York, 1956)

- J. T. McIntosh, Rule of the Pagbeasts (Crest 150, 1956)

- Sylvia Tate, The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown (Harper, 1956)

- Anon. [Gladys Parrish], Madame Solario: A Novel (Viking, 1956)

- Carl Carmer, The Screaming Ghost (Knopf, 1956)

- Booton Herndon, Bergdorf's in the Plaza (Knopf, 1956)

- Norman Dale, The Casket and the Sword (Harper, 1956)

- Nora Benjamin Kubie, King Solomon's Horses (Harper, 1956)

- Lincoln Steffens, The Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens (Grosset & Dunlap Universal Library, 1956)

- John P. Marquand, The Late George Apley (Grosset & Dunlap Universal Library, 1956)

- Carlo Levi, Christ Stopped at Eboli (Grosset & Dunlap Universal Library, 1956)

- Norman Douglas, South Wind (Grosset & Dunlap Universal Library, 1956)

- John Steinbeck, The Wayward Bus (Grosset & Dunlap, 1956)

- Herman Melville, Typee (Grosset & Dunlap, 1956)

- Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace (Grosset & Dunlap, 1956)

- Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Brothers Karamazov (Grosset & Dunlap, 1956)

- Benjamin Appel, We Were There in the Klondike Gold Rush (Grosset & Dunlap, 1956)

- W. R. Burnett, Pale Moon (Knopf, 1956)

- Leonard Bishop, Creep Into Thy Narrow Bed (Pyramid G206, 1956)

- Erskine Caldwell, Georgia Boy (Grosset & Dunlap, 1957)

- Erskine Caldwell, God's Little Acre (Grosset & Dunlap, 1957)

- Erskine Caldwell, The Sure Hand of God (Grosset & Dunlap, 1957)

- Erskine Caldwell, Tobacco Road (Grosset & Dunlap, 1957)

- Erskine Caldwell, Tragic Ground (Grosset & Dunlap, 1957)

- Maria Bellonci, The Life And Times of Lucrezia Borgia (Grosset & Dunlap Universal Library, 1957)

- Zsolt de Harsanyi, The Star-Gazer (Grosset & Dunlap Universal Library, 1957)

- Mary Freeman, D. H. Lawrence: A Basic Study of His Ideas (Grosset & Dunlap Universal Library, 1957)

- Herman Melville, The Shorter Novels (Grosset & Dunlap Universal Library, 1957)

- Lloyd Lewis, Myths after Lincoln (Grosset & Dunlap Universal Library, 1957)

- Henrik Ibsen, Four Plays of Henrik Ibsen (Grosset & Dunlap Universal Library, 1957)

- Benjamin Appel, We Were There at the Battle for Bataan (Grosset & Dunlap, 1957)

- William Goldman, The Temple of Gold (Knopf, 1957)

- Ercole Patti, A Roman Affair (William Sloane, 1957)

- Vinnie Williams, The Fruit Tramp (Harper, 1957)

- Francis Steegmuller, Maupassant: A Lion on the Path (Grosset & Dunlap Universal Library, 1958)

- James Mitchell, The Lady is Waiting (Morrow, 1958)

- Elizabeth Cadell, Shadows on the Water (Morrow, 1958)

- Marjorie G. Fribourg, Benkei the Boy-Giant (Sterling, 1958)

- Marjorie G. Fribourg, Bimo: Young Hero of Japan (Sterling, 1958)

- Ben Botkin and Carl Withers, The Illustrated Book of American Folklore (Grosset & Dunlap, 1958)

- Richard Bissell, Say, Darling (Atlantic / Little, Brown, 1958)

- Monica Stirling, Sigh for a Strange Land (Little, Brown, 1958)

- John Coates, The Widow’s Tale (William Sloane, 1958)

- Pauline Rush Evans, Good Housekeeping's Best Book of Mystery Stories (Good Housekeeping Magazine, 1958)

- Lillian and Godfrey Frankel, A Scrapbook of Real-Life Stories for Young People (Sterling, 1958)

- Christine Noble Govan and Emmy West, Mystery of the Vanishing Stamp (Sterling, 1958)

- Christine Noble Govan and Emmy West, Mystery at the Haunted House (Sterling, 1959)

- Christine Noble Govan and Emmy West, Mystery at Plum Nelly (Sterling, 1959)

- Christine Noble Govan and Emmy West, Mystery at Fearsome Lake (Sterling, 1960)

- Christine Noble Govan and Emmy West, Mystery at Rock City (Sterling, 1960)

- Christine Noble Govan and Emmy West, Mystery at the Snowed-In Cabin (Sterling, 1961)

- Christine Noble Govan and Emmy West, Mystery at the Echoing Cave (Sterling, 1965)

- John Dickson Carr, Scandal at High Chimneys (Harper, 1959)

- General de Caulaincourt, With Napoleon in Russia (Grosset & Dunlap Universal Library, 1959)

- August Strindberg, Letters of Strindberg to Harriet Bosse (Grosset & Dunlap Universal Library, 1959)

- Margery Sharp, The Eye Of Love (Little, Brown, 1959)

- James Wellard, The Affair In Arcady (Reynal, 1959)

- Dorothy Lee, Freedom and Culture: A Unique View of the Individual in His Society (Prentice Hall, 1959)

- Willa Gibbs, The Dedicated: A Novel of Two Doctors (Morrow, 1959)

- Julian Mayfield, The Hit (Pocket 1229, 1959)

- Samuel Butler, The Way of All Flesh (Washington Square Press W561, 1959)

- Francoise des Ligneris, Psyche 59 (Avon T-482, 1959)

- Francoise des Ligneris, Fort Frederick (Avon #T-456, 1960)

- Helen McCloy, The Slayer and the Slain (1960)

- Muse A. Norcross, Li-Ho of the Boat People (Franklin Watts, 1960)

- Alexander Rose, Four Horse Players are Missing (Coward-McCann, 1960)

- Charmian Clift, Walk to the Paradise Gardens (Harper, 1960)

- Alice Ekert-Rotholz, A Net of Gold (Viking, 1960)

- Murray Gitlin, All the Voices (Coward-McCann, 1960)

- Louis Vaczek, The Troubadour (William Sloane, 1960)

- Marjorie Vetter, Journey for Jennifer (Scholastic, 1960)

- Edgar Allan Poe, Ten Great Mysteries, ed. Groff Conklin (Scholastic T-210, 1960)

- Edgar Allan Poe, Eight Tales of Terror (Scholastic T-290, 1961)

- Lawrence Williams, The Fiery Furnace (Avon T-497, 1961)

- Jose Luis De Vilallonga, The Man of Blood (Berkley Medallion G503, 1961)

- Peter Elstob, Warriors for the Working Day (Coward-McCann, 1961)

- Guy de Maupassant, Contes Choisis (Doubleday, 1961)

- Elliott Arnold, Brave Jimmy Stone (Knopf, 1962)

- Ervin Seale, Learn to Live: The Meaning of the Parables (Morrow, 1962)

- Anne Colver, Abraham Lincoln for the People (Scholastic TW359, 1962)

- Philip Van Doren Stern, Great Ghost Stories (Washington Square Press 592, 1962)

- Mary MacEwan, ed., Stories of Suspense (Scholastic T 487, 1963)

- Robert A. Heinlein, Glory Road (Putnam, 1963)

- Robert A. Heinlein, Podkayne of Mars (Putnam, 1963)

- Robert A. Heinlein, Farnham's Freehold (Putnam, 1964)

- Robert A. Heinlein, Orphans of the Sky (Putnam, 1964)

- Robert A. Heinlein, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress (Putnam, 1966)

- Robert Arthur, Ghosts and More Ghosts (Random House, 1963)

- Roger Fulford, George the Fourth (Capricorn CAP 78, 1963)

- Dorothy M. Fraser, Discovering Our World's History (American Book Company, 1964)

- Charlotte Jay, A Hank of Hair (Harper, 1964)

- Oscar Pinkus, Friends & Lovers (Midwood Tower 347, 1964)

- Alan Riefe, Tales of Horror (Scholastic 10063, 1965)

- James Blish, Mission to the Heart Stars (Putnam, 1965)

- Jakov Lind, Soul of Wood and Other Stories (Crest R897, 1966)

- Daoma Winston, The Wakefield Witches (Award 0185, 1966)

Record albums

- Ellabelle Davis, Ellabelle Davis Sings Negro Spirituals (Camden LPS 182, 1950)

- Ernest Bloch, Schelomo: Hebraic Rhapsody for 'Cello and Orchestra, conducted by the composer (London LPLS 138)

- Edvard Grieg, Peer Gynt, conducted by Basil Cameron (London LLP 153, 1950)

- Harry Fryer and His Orchestra, March Medley (London LPB 197)

- Ronnie Munro and His Orchestra, Ballet Memories (London LPB 215)

- Richard Strauss, Also Sprach Zarathustra (London LLP 232)

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Symphony No. 6 ("Pathetique") (London LLP 257)

- The Robert Farnon Octet, Stephen Foster Melodies (London LPB 258)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Die Entfuhrung aus dem Serail / Abduction From The Seraglio, dir. Josef Krips (London LLP A3)

- Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 9 (Record of the Month Club, 1956)

- Prince Onago & Princess Muana & Native Drummers of the Belgian Congo: The Drums of Africa (20th Century Fox FOX 3000, 1959)

- Djamal Aslan, Lebanon: Her Heart, Her Sounds (20th Century Fox FOX 3001, 1959)

- Nina Dova, Child of the Sun: Songs from the Torrid Zone (20th Century Fox FOX 3014, 1959)

- Enrico Simonetti Orchestra, Bravissimo! (20th Century Fox FOX 3015, 1959)

- Hugo Montenegro with 20th Century Strings, 20th Century Strings, Volume 1 (20th Century Fox FOX 3018, 1959)

- Glenn Miller & His Orchestra, Original Film Soundtracks, Volume 1 (20th Century Fox FOX 3020, 1959)

- Glenn Miller & His Orchestra, Original Film Soundtracks, Volume 2 (20th Century Fox FOX 3021, 1959)

- Tommy Dorsey and His Greatest Band Vol. 1 (20th Century Fox FOX 3022, 1959)

- Tommy Dorsey and His Greatest Band Vol. 2 (20th Century Fox FOX 3023, 1959)

- Woof Whistler & His Terriers, "Woof" (20th Century Fox FOX 3024, 1960)

- Al Martino, Al Martino (20th Century Fox FOX 3025, 1960)

- The Dixie Double-Cats, Is It True What They Say About Dixie? (20th Century Fox FOX 3027, 1960)

- The Dew Drops, Rain (20th Century Fox FOX 3028, 1960)

- Art Tatum, Discoveries (20th Century Fox FOX 3029/SFX 3029, 1960)

- Hugo Montenegro with 20th Century Strings, Great Standards: The 20th Century Strings, Volume 3 (20th Century Fox FOX 3030, 1960)

- Art Tatum, Piano Discoveries (20th Century Fox FOX 3033/SFX 3033, 1960)

- Jon Ern and the Olympic Festival Orchestra, Songs of the Olympic Years (20th Century Fox FOX 3042, 1961)

- 20th Century Strings, Twelve Great Themes of the Soaring 60s, (20th Century Fox SFX-3043, 1961)

- Harry Simeone Chorale, The Little Drummer Boy (20th Century Fox TFM 3100, 1963)

- Serendipity Singers, Love Is a State of Mind (United Artists UAS 6619, 1967)

Magazines (partial list)

- Ace

- All Girls

- Amazing

- Applause

- Boys' Life

- Calling All Girls

- Cavalcade"

- Children's Digest

- Christian Herald

- Collier's

- Compact

- Coronet

- Creepy

- Escapade

- Every Woman

- Family Weekly (Chicago)

- Galaxy Science Fiction

- Gent

- Gourmet

- Harpers

- Hi-Life

- High

- House Beautiful

- Life Magazine

- Management Review

- Mineral Digest

- Monsieur

- Nugget

- Pageant

- Parent's Magazine

- Playboy

- Redbook

- Rex

- The Saint Mystery Magazine

- Snowflake

- Suburbia (Chicago)

- Tween

- Westminster

- Women of Italy

- Women of the Orient

- Young Americans

Bibliography

- "The Art of Irv Docktor". Cavalcade, December 1963.

- "In Memoriam: Irv Docktor". Portfolio (Philadelphia Sketch Club), May 2008.

References

- ↑ Frank L. Schick, The Paperbound Book in America: The History of Paperbacks and their European Background (New York: RR Bowker, 1958), p. 194.

- ↑ In Memoriam: Irv Docktor". Portfolio (Philadelphia Sketch Club), May 2008.

- ↑ "The Art of Irv Docktor," Cavalcade, December 1963.

- 1 2 3 4 Sloan, Michael (February 26, 2008). "Irv Docktor 1918-2008". Michael Sloan.

- ↑ "Himmelstein, Morris M." The Baltimore Sun. July 5, 2006.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Irv Docktor. |

- Official website

- In Memoriam: Irv Docktor

- B. Docktor photography

- Works by Irv Docktor at Project Gutenberg