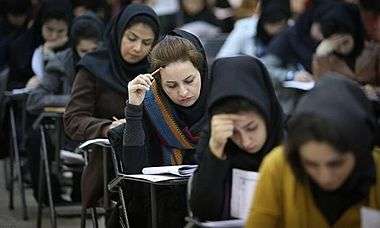

Iranian University Entrance Exam

The Iranian University Entrance Exam also known as the Concours (from the French; Konkoor, Konkour, and Konkur are transliterations of the Persian) is a standardized test used as one of the means to gain admission to higher education in Iran. Generally, to get Ph.D. in non-medical majors, there are 3 exams, all of them called Concour. In recent years there was parliament bill to gradually eliminate this entrance exam to enter universities in Iran.

Nationwide

In June each year, high school graduates in Iran take a stringent, centralized nationwide university entrance exam, called the Concours, seeking a place in one of the public universities. The competition is fierce and the exam content rigorous since the seats at universities are limited. In recent years, although the government has responded to demands for improved access and to a rapid increase in the rising number of applicants by enlarging the capacity of universities and creating Azad University, public universities are still only able to accept 10 percent of all applicants.

History and trends

In Iran, as in many other countries where a university entrance exam is a sole criterion for student selection, limited space and resources have restricted many talented and enthusiastic applicants seeking access to higher education. Concours is a comprehensive, 4.5-hour multiple-choice exam that covers all subjects taught in Iranian high schools—from math and science to Islamic studies and foreign language. The exam is so stringent that normally students spend a year preparing for it; those who fail are allowed to repeat the test in the following years until they pass it.

A very lucrative cram industry offers courses to enthusiastic students. The Ministry of Science, Research, and Technology has established the Education Evaluation Organization to oversee all aspects of the test.

As the sole criterion for student admissions into universities in Iran, Concours has gone through many phases. In prerevolutionary Iran, the exam was—as currently—a comprehensive test of knowledge and assessment of academic achievement for admissions. However, the problem in this era was that the selection methods provide advantages to candidates from urban areas, especially those from the upper and upper-middle classes with better education and preparation. Thus, almost 70 to 80 percent of university entrants came from large urban cities.

In the early years of postrevolutionary Iran, the purpose of testing shifted from being just a mere test of knowledge to an instrument to ensure the "Islamization of universities," aimed at admitting students committed to the ideology of the revolution. The university entrance exam judged admissions candidates not only by their academic test score but also by their social and political background and loyalty to the Islamic government.

In the early 1980s, a quota system was introduced to further democratize the selection criteria by allowing preferential treatments to underprivileged students. A year after the Iran-Iraq war ended, a law was passed to help handicapped and volunteer veterans to enter universities, reserving 40 percent of university seats for war veterans.

An additional criterion for student selection was introduced in the early 1990s to localize the student population, giving priority to candidates who applied to study in their native provinces. This policy was to prevent student migration into the larger cities. The requirement of service after graduation also was instrumental in providing education and health to the needy areas.

Ongoing problems

Despite attempts made in recent years to reform university selection criteria and to promote the equalization of educational opportunities, the Concours remains an impediment to equal education access. Both quantitatively and qualitatively, the quota criteria have worked against students whose academic performance is superior to those favored by the quota system. Another factor that contributes to the phenomenon of student elimination is the lack of infrastructure and facilities in spite of the expansion of infrastructure and establishment of an "open" university, Azad University. Azad University, a semi private university, favors its autonomy in governance, but its degrees and curriculum are overseen by the Ministry of Science, Research, and Technology.

The other drawback is the nature of the test itself. As in many other countries where only a long multiple-choice, mostly memory-based exam is used to select qualified applicants to enter universities, Iranian schools have been turned into factories for exam cramming.

Concours, especially in recent years, has further contributed to the massive brain drain from Iran and has created psychological and social problems such as anxiety, boredom, and hopelessness among the youth who fail the test.

Reform options

In Iran, admission to university—especially prestigious public and highly selective universities such as Tarbiat Modares University, University of Tehran, Sharif University of Technology,Iran University of Science and Technology(IUST), Amirkabir University of Technology(AUT), and Isfahan University of Technology —remains a means of achieving elevated status in a society where education is a major determinant of class mobility. Graduates of such universities have a better chance of securing the increasingly limited jobs in the prestigious professions in Iran—medicine, engineering, law—making success in the entrance exam the first and perhaps the most important hoop through which Iranian youths must jump.

As the Concours crisis persists, authorities are contemplating a replacement mechanism for student selection. One of the options being considered is to use the cumulative grade-point average (GPA) of the final three years of high school to admit students. While this policy seems more humanistic and fair than using a single exam to measure students' preparedness, it still cannot ensure fairness or reveal students' aptitude for further learning. Perhaps incorporating interviews, essay writing, and aptitude tests, in addition to GPA would be a more effective way of measuring students' qualifications to enter universities.

Another long-term approach to remedy the Concours crisis in Iran would be to rely on midcareer education and training in place of the precareer pattern of university education by introducing the community college concept into the education system of Iran. This approach could serve to divert less academically inclined students from participating in the university entrance exams and hopefully eventually alleviate the Concours crisis.

See also

- SAT, the US equivalent

- List of admissions tests

- List of universities in Iran

- Higher education in Iran

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iranian University Entrance Exam. |

References

- Shahrzad Kamyab. "International Higher Education, Spring 2008, No. 51". Archived from the original on 9 June 2008.