Involuntary unemployment

Involuntary unemployment occurs when a person is willing to work at the prevailing wage yet is unemployed. Involuntary unemployment is distinguished from voluntary unemployment, where workers choose not to work because their reservation wage is higher than the prevailing wage. In an economy with involuntary unemployment there is a surplus of labor at the current real wage. Involuntary unemployment cannot be represented with a basic supply and demand model at a competitive equilibrium: All workers on the labor supply curve below the market wage would voluntarily choose not to work, and all those above the market wage would be employed. Given the basic supply and demand model, involuntarily unemployed workers lie somewhere off of the labor supply curve.[1] Economists have several theories explaining the possibility of involuntary unemployment including implicit contract theory, disequilibrium theory, staggered wage setting, and efficiency wages.[1]

Explanations

Models based on implicit contract theory, like that of Azariadis (1975), are based on the hypothesis that labor contracts make it difficult for employers to cut wages. Employers often resort to layoffs rather than implement wage reductions. Azariadis showed that given risk-averse workers and risk-neutral employers, contracts with the possibility of layoff would be the optimal outcome.[2]

Efficiency wage models suggest that employers pay their workers above market clearing wages in order to enhance their productivity.[1] In efficiency wage models based on shirking, employers are worried that workers may shirk knowing that they can simply move to another job if they are caught. Employers make shirking costly by paying workers more than the wages they would receive elsewhere. This gives workers an incentive not to shirk.[1] When all firms behave this way, an equilibrium is reached where there are unemployed workers willing to work at prevailing wages.[3]

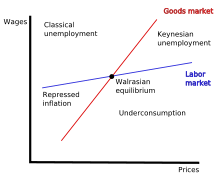

Following earlier disequilibrium research including that of Robert Barro and Herschel Grossman, work by Edmond Malinvaud clarified the distinction between classical unemployment, where real wages are too high for markets to clear, and Keynesian unemployment, involuntary unemployment due to inadequate aggregate demand.[1] In Malinvaud's model, classical unemployment is remedied by cutting the real wage while Keynesian unemployment requires an exogenous stimulus in demand.[5] Unlike implicit contrary theory and efficiency wages, this line of research does not rely on a higher than market-clearing wage level. This type of involuntary unemployment is consistent with Keynes's definition while efficiency wages and implicit contract theory do not fit well with Keynes's focus on demand deficiency.[6]

Perspectives

For many economists, involuntary unemployment is a real-world phenomenon of central importance to economics. Many economic theories have been motivated by the desire to understand and control involuntary unemployment.[7] However, acceptance of the concept of involuntary unemployment isn't universal among economists. Some do not accept it as a real or coherent aspect of economic theory.

Shapiro and Stiglitz, developers of an influential shirking model, stated "To us, involuntary unemployment is a real and important phenomenon with grave social consequences that needs to be explained and understood."[8]

Mancur Olson argued that real world events like the Great Depression could not be understood without the concept of involuntary unemployment. He argued against economists who denied involuntary unemployment and put their theories ahead of "common sense and the observations and experiences of literally hundreds of millions of people... that there is also involuntary unemployment and that it is by no means an isolated or rare phenomenon."[9]

Other economists do not believe that true involuntary unemployment exists[10] or question its relevance to economic theory. Robert Lucas claims "...there is an involuntary element in all unemployment in the sense that no one chooses bad luck over good; there is also a voluntary element in all unemployment, in the sense that, however miserable one's current work options, one can always choose to accept them"[11] and "the unemployed worker at any time can always find some job at once."[11] Lucas dismissed the need for theorists to explain involuntary unemployment since it is "not a fact or a phenomenon which it is the task of theorists to explain. It is, on the contrary, a theoretical construct which Keynes introduced in the hope it would be helpful in discovering a correct explanation for a genuine phenomenon: large-scale fluctuations in measured, total unemployment."[12] Along those lines real business cycle and other models from Lucas's new classical school explain fluctuations in employment by shifts in labor supply driven by changes in workers' productivity and preferences for leisure.[1]

Involuntary unemployment is also conceptually problematic with search and matching theories of unemployment. In these models, unemployment is voluntary in the sense that a worker might choose to endure unemployment during a long search for a higher paying job than those immediately available; however, there is an involuntary element in the sense that a worker does not have control of the economic circumstances that force them to look for new work in the first place.[13]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Taylor 2008.

- ↑ De Vroey 2002, p. 384.

- ↑ Shapiro & Stiglitz 1984.

- ↑ Tsoulfidis 2010, p. 294.

- ↑ De Vroey 2002, p. 383.

- ↑ De Vroey 2002, p. 383-385.

- ↑ McCombie 1987, p. 203.

- ↑ Shapiro & Stiglitz 1985, p. 1217.

- ↑ Olson 1982, p. 195.

- ↑ Mayer 1997, p. 94.

- 1 2 Lucas 1978, p. 354.

- ↑ Lucas 1978, p. 354-355.

- ↑ Andolfatto 2008.

References

| Library resources about Involuntary unemployment |

- Andolfatto, David (2008), "Search models of unemployment.", in Durlauf, Steven N.; Blume, Lawrence E., The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics (Second ed.), Palgrave Macmillan, doi:10.1057/9780230226203.1497, retrieved 21 April 2013

- Azariadis, C. (1975). "Implicit contracts and underemployment equilibria". Journal of Political Economy. 83: 1183–202. doi:10.1086/260388.

- De Vroey, Michel (2002). "Involuntary unemployment in Keynesian economics". In Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard. An Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 381–385. ISBN 978-1-84542-180-9.

- Lucas, Robert E. (May 1978), "Unemployment policy", American Economic Review, 68 (2): 353–357, JSTOR 1816720

- Mayer, Thomas (1997), "What Remains of the Monetarist Counter-Revolution?", in Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard R., Reflections on the Development of Modern Macroeconomics, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 55–102, ISBN 978-1-85898-342-4

- McCombie, John S. (Winter 1987–1988). "Keynes and the Nature of Involuntary Unemployment". Journal of Post Keynesian Economics. 10 (2): 202–215. doi:10.1080/01603477.1987.11489673. JSTOR 4538065.

- Olson, Mancur (1982). The rise and decline of nations : economic growth, stagflation, and social rigidities. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300030792.

- Shapiro, C.; Stiglitz, J. E. (1984). "Equilibrium Unemployment as a Worker Discipline Device". The American Economic Review. 74 (3): 433–444. doi:10.2307/1804018.

- Shapiro, Carl; Stiglitz, Josephy E. (December 1985), "Can Unemployment Be Involuntary? Reply", The American Economic Review, 75 (5): 1215–1217, JSTOR 1818667

- Taylor, John B. (2008), "Involuntary Unemployment.", in Durlauf, Steven N.; Blume, Lawrence E., The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics (Second ed.), Palgrave Macmillan, doi:10.1057/9780230226203.0850, retrieved 20 April 2013

- Tsoulfidis, Lefteris (2010). Competing schools of economic thought. London: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-92692-4.