Iazyges

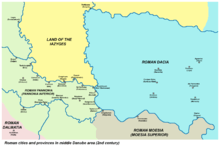

The Iazyges IPA: ['aɪɯzɪɡeːz] were an ancient Sarmatian nomadic tribe who swept westward from Central Asia onto the steppes of what is now Ukraine in c. 200 BC and then, in the 1st century BC, further into Hungary and Serbia, settling near Dacia, in the steppe between the Danube and Tisza rivers.

They were often at war or else in dispute with Rome in their early history, with them raiding the Romans and the Romans occasionally sending a punitive expedition to discourage future raids. However, later in in their history they came to be used by Rome as a buffer tribe-state, following the adoption of a policy of using small, non-powerful states or tribes to block the invasions of large or powerful threats.

The Iazyges are mentioned by the geographer Claudius Ptolemy in his Geography as the "Wandering Iazyges" (Ἰάζυγες Μετανάσται, Iázyges Metanástai). Their name was variously Latinized as Iazyges Metanastae and as Jazyges.[1]

History

The Iazyges first make their appearance in the historical record on the northern shores of the Lake of Maeotis (as the Ancient Greeks and Romans knew the Sea of Azov, in modern south-east Ukraine). From there, the Iazyges moved west along the shores of the Black Sea into modern Moldova and southwest Ukraine.[2][3]

2nd century BC

In the 2nd century BC, the Roxolani, under pressure from the Aorsi, moved west, displacing the Iazyges and forcing them to migrate west, to the steppe near the Lower Dniester. However, the land there was already occupied by the Basternae, and Getae, so they turned southward, following the coast of the Black Sea until they settled in the Danube delta.[4]

1st century BC

From 78 to 76 BC, the Romans led an expedition to an area north of the Danube, then the Iazyges' territory, because the Iazyges had allied with Mithradates VI of Pontus, with whom the Romans were at war.[5][6] In 44 BC King Burebista of Dacia died, and his kingdom began to collapse. After this, the Iazyges began to take possession of the Pannonian Basin, the land between the Danube and the Tisa rivers (modern south-central Hungary).[7]

1st century AD

In 6 AD and again in 16 AD, the Iazyges raided their border with Rome. However, in 20 AD the Iazyges moved west along the Carpathians into the Hungarian steppes, and settled in the steppes between the Danube and the Tisza river, fully taking it from the Dacians.[4] In 50 AD, an Iazyges cavalry detachment fought alongside the Suevian King Vannius, who was a Roman client king of the Quadi.[8]

In 69 AD, the Year of Four Emperors, the Iazyges backed Vespasian, who went on to become sole emperor of Rome. Vespasian enjoyed support from the majority of the Germanic and Dacian tribes.[9] The Iazyges also offered to guard the Roman border with the Dacians, in order to free up troops for Vespasian's invasion of Italy; however, Vespasian refused, fearing that they would either attempt a takeover or defect.[10]

In early 92 the Iazyges and the Roxolani allied themselves to the Dacians and the Suebi, and crossed the Danube into the Roman province of Pannonia (modern Croatia, northern Serbia, and western Hungary). Domitian, who was devoting most of his army to attacking them near the Danube, called upon the Quadi and the Marcomanni to supply troops. They refused, and Rome declared war upon them as well. In May 92, the Iazyges shattered the Roman Legio XXI Rapax in battle.[11] Domitian's campaign was entirely unsuccessful; however, a victory in a minor skirmish allowed him to claim it a victory, even though he ended up paying the King of Dacia, Decebalus, an annual tribute of eight million sesterces in tribute to end the war.[9][12] He returned to Rome, and received an ovation, but not a full triumph. For a man who had been given the title of Imperator for military victories 22 times, this was markedly restrained, suggesting that the populace, or at least the senate, was aware of the fact that it had been a less than successful war, despite Domitian's claims otherwise.[11]

During the Flavian dynasty, the kings of the Iazyges were trained in the Roman army, officially as an honor, but serving also the purpose of a hostage, because the kings held absolute power over the Iazyges.[13] There were offers from the Iazyges kings to supply troops, but these were denied based on the fear that they might revolt or desert in a war.[14]

By the turn of the 1st century, Roman military resources had become centred along the Danube instead of the Rhine. Under Augustus, there were four legions stationed along the Rhine, with four being stationed in Mainz and another four in Cologne.[9] However, this number changed to one along the Rhine and nine along the Danube within a hundred years. By the time of Marcus Aurelius, twelve legions were stationed along the Danube.[15]

2nd century AD

An alliance between the Iazyges and the Dacians led the Romans to focus more on the Danube than the Rhine. The Romans built a series of forts along the entire coast of the right Danube – from Germany all the way to the Black Sea and in the provinces of Rhaetia, Noricum, and Pannonia the legions constructed bridge-head forts. Later, this system was expanded to the lower Danube, with the key castra of Poetovio, Brigetio, and Carnuntum. The defence of the Danube was much more difficult than that of the Rhine, due to the sharp angle of the river. The Classis Pannonica and Classis Flavia Moesica were deployed to the right and lower Danube, respectively; however, they had to overcome the mass of whirlpools and cataracts of the Iron Gates.[15]

First Dacian War

In 101 AD, Trajan, with the assistance and troops of the Iazyges, led his legions into Dacia against King Decebalus.[16] In order to cross the Danube with such a large army, Apollodorus of Damascus, the Romans' chief architect, created a bridge through the Iron Gates by cantilevering it from the sheer face of the Iron Gates. From this he created a great bridge with sixty piers that spanned the Danube. Trajan used this to strike deep within Dacia, forcing the king, Decebalus, to surrender and become a client king.[17]

Second Dacian War

But as soon as Trajan returned to Rome, Decebalus began to lead raids into Rome. Trajan concluded that he had made a mistake in allowing Decebalus to remain so powerful.[17] In 106 AD, Trajan once more invaded Dacia, with 11 legions, and, again with the assistance of the Iazyges,[16] rapidly pushed into Dacia. Decebalus chose to commit suicide rather than be captured, knowing that, if he were, he would be paraded in a triumph before being executed. In 113 AD Trajan annexed Dacia as a new Roman province, the first Roman province to the east of the Danube. Back in Rome, Trajan was given a triumph lasting 123 days, with lavish gladiatorial games, and chariot races. The wealth coming from the gold mines of Dacia funded these lavish public events, and also the construction of a column, designed and constructed by Apollodorus of Damascus, that was 100 feet (30 m) tall with 23 spiral bands filled with 2,500 figures, giving a full depiction of the Dacian war. While ancient sources say 500,000 slaves were taken in the war, moderns sources believe that it was probably closer to 100,000 slaves.[18] Trajan did not incorporate the steppe between the Tisza river and the Transylvanian mountains into the province of Dacia, but left it for the Iazyges.[19]

After the Dacian Wars

There was a dispute about the ownership of Oltenia between the Roman empire, who owned it, and the Iazyges, who had owned it before the Dacians took it from them. Trajan was determined to constitute Dacia as a province, and so refused to relinquish it. The dispute was later resolved in a peace treaty after Hadrian invaded the Iazyges. The exact terms of the peace are not known, but it is believed that the Romans kept Oltenia but made some form of concession, likely a one-time tribute payment.[19] It is, however, known that the Iazyges took possession of Banat around this time, suggesting it may have been part of the treaty.[20]

In 117 AD, the Iazyges and the Roxolani invaded Lower Pannonia and Lower Moesia, respectively, the reason for the war likely being difficulties in communication due to the location of Dacia between them. The Dacian provincial governor, C. Julius Quadratus Bassus, was killed in the invasion. The Roxolani surrendered first, so it is likely that the Romans replaced their client king and exiled the other king. The Iazyges concluded peace by sending an embassy to Rome, where it is believed they became a client state of Rome. Whatever the treaty was, it appears to have been satisfactory to the Iazyges, as no wars between Rome and them are recorded for another half century.[21]

In 123 AD, after the Iazyges and other Sarmatians invaded Roman Dacia, Marcius Turbo stationed troops in Potaissa and Porolissum under the command of Octavio Grapo. The Romans probably used these towns as the invasion point into Rivulus Dominarum. Marcius Turbo succeeded in defeating the Iazyges; however, the terms of the peace, and the date, are not known.[22]

In 169 AD the Iazyges, Quadi, and Marcomanni invaded Rome. Marcus Claudius Fronto, a former general during the Parthian wars, then the governor of both Dacia and Upper Moesia, held them back for some time but was killed in battle in 170 AD.[23] The Quadi were the first to surrender, in 172 AD. The known terms of the peace are that Marcus Aurelius installed a client king, Furtius, on their throne, and the Quadi were denied access to the Roman markets along the Limes. The Marcomanni accepted a similar peace, but the name of their client-king is not known.[24]

In 173 AD the Quadi rebelled and overthrew Furtius, and replaced him with Ariogaesus, who wanted to enter into negotiations with Marcus, who, as the success of the Marcomannic wars was in no danger, he refused to negotiate.[24] Also in 173, only the Iazyges remained undefeated. Judging from the lack of action on Marcus Aurelius' part, it appears he was unconcerned, but when the Iazyges attacked across the frozen Danube in late 173 and early 174 AD, Marcus redirected his attention to them. At the same time, the trade restrictions on the Marcomanni were partially lifted – they were allowed to visit the Roman markets at certain times of certain days. In an attempt to force Marcus to negotiate with him, Ariogaesus began to support the Iazyges.[25] It is known that Marcus Aurelius put out a bounty on him, offering 1,000 gold pieces if brought to him alive, and 500 gold pieces if they killed him and brought him his head.[26] After this, Ariogaesus was captured by the Romans, and rather than executing him, Marcus Aurelius exiled him.[27] The Iazyges probably surrendered in 175. It is known that their king, Banadaspus, attempted peace in early 174 AD; however, when he was refused, he was deposed by the Iazyges and replaced by Zanticus.[25]

The conditions of the peace were very harsh: the Iazyges could not live within ten Roman miles (roughly 9 miles or 15 km) of the Danube and had to provide 8,000 men as auxiliaries and give back 100,000 Romans they had taken hostage. Marcus had intended to give even harsher terms, but was distracted by the rebellion of Avidius Cassius.[25] It is said that he wanted to entirely exterminate the Iazyges.[28] Of the 8,000 auxiliaries, 5,500 of them were sent to Britannia, suggesting that the situation there was serious; it is likely that the British tribes, seeing the Romans being preoccupied with war in Germania and Dacia, had decided to rebel. All of the evidence suggests that the Iazyges' horsemen were a striking success, and some believe that the unusually armored horsemen may have been an inspiration for the King Arthur myth.[29]

In 177 AD the Iazyges and some German tribes invaded Rome again. In 179 the Iazyges and the Buri were defeated, and the Iazyges accepted peace with Rome. The peace added to restrictions placed on the Iazyges, but also included some concessions. It stated that they could not settle on any of the islands of the Danube, and could not keep boats on the Danube; however, they were given the concession that they could communicate with the Roxolani throughout the Dacian Province with the knowledge and approval of its governor, and that they could trade in the Roman markets at certain times on certain days.[30] In 183 AD Commodus forbid the Quadi and the Marcomanni to make war on the Iazyges, Buri, or Vandals, suggesting that at this time all three of them were loyal client tribes of Rome.[31]

In 184 AD the 5,500 Iazyges auxiliaries, or else replacements for them, were led by the Roman general Lucius Artorius Castus to put down a revolt in Armorica (Northern Gaul).[32] During the second century, some Roman cavalry came to adopt the Iazyges weapons and equipment, such as the metal scale armor, barding horses, and long, two-handed lances (Contus).[33]

5th century AD

In 472 AD the Visigothic king, Theoderic the Great, conquered the Iazyges and killed their co-kings, Babay and Beuca.[34][35][36]

Aftermath and legacy

In late antiquity, records become much more diffuse, and the Iazyges generally cease to be mentioned as a tribe. In the 4th century, two Sarmatian peoples were mentioned, the Argaragantes and the Limigantes, who lived on opposite sides of the Tisza river.[37]

It has been theorized that the Iazyges gave their name to the Jazones in Hungary or to the Romanian city of Iași (pronounced jaʃʲ).[38]

List of kings

- Banadaspus: ? – 174 AD[25]

- Zanticus: 174 AD–?[25]

- Uzafer ? – c. 358 AD

- Zizayis c. 358–?

- Beuca and Babay: co-rulers in 470–471 AD[35]

See also

References

Notes

- 1.^ Presumably around nine because during this period nine legions were permanently stationed around the Danube.[15]

- 2.^ It is unspecified, but is presumed to be the Roxolani, due to their close geographical location, and their history of working together on raids, especially raids against Rome.

- 3 ^ The likely reason for Marcus Aurelius offering more for him alive than dead is that he wanted to parade him in a triumph.

Citations

- ↑ Smith, William (1873). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (2nd ed.). J. Murray. p. 7.

- ↑ McLynn, Frank (2010). Marcus Aurelius: A Life. Da Capo Press. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-306-81916-2.

- ↑ Grumeza, Ion (2009). Dacia: Land of Transylvania, Cornerstone of Ancient Eastern Europe. Lanham: Hamilton Books. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-7618-4466-2.

- 1 2 Cunliffe, Barry (2015). By Steppe, Desert, and Ocean: The Birth of Eurasia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-19-968917-0.

- ↑ Hildinger, Erik (2001). Warriors of the Steppe: A Military history of Central Asia, 500 B.C. to 1700 A.D. Cambridge, Mass: Da Capo. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-306-81065-7.

- ↑ Hinds, Kathryn (2010). Scythians and Sarmatians. New York: Marshall Cavendish Benchmark. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7614-4519-7.

- ↑ Mócsy, András (Apr 8, 2014). Pannonia and Upper Moesia (Routledge Revivals): A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-317-75425-1.

- ↑ Malcor, Linda A.; Littleton, C. Scott (2013). From Scythia to Camelot A Radical Reassessment of the Legends of King Arthur, the Knights of the Round Table, and the Holy Grail. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-317-77771-7.

- 1 2 3 McLynn, Frank (2010). Marcus Aurelius: A Life. Da Capo Press. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-306-81916-2.

- ↑ McLaughlin, Raoul (2016). The Roman Empire and the Silk Routes: The Ancient World Economy and the Empires of Parthia, Central Asia and Han China. Casemate Publishers. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-4738-8982-8.

- 1 2 Grainger, John D. (2004). Nerva and the Roman succession crisis of AD 96–99. London: Routledge. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-415-34958-1.

- ↑ Jones, Brian W. (1993). The Emperor Domitian (New ed.). London [u.a.]: Routledge. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-415-10195-0.

- ↑ Wellesley, Kenneth (2002). Year of the Four Emperors. Routledge. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-134-56227-5.

- ↑ Ash, Tacitus; translated by Kenneth Wellesley; revised with a new introduction by Rhiannon (2009). The Histories (Rev. ed.). London: Penguin Books. p. 3.5. ISBN 978-0-14-194248-3.

- 1 2 3 McLynn, Frank (2010). Marcus Aurelius: A Life. Da Capo Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-306-81916-2.

- 1 2 Mócsy, András (Apr 8, 2014). Pannonia and Upper Moesia (Routledge Revivals): A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-317-75425-1.

- 1 2 McLynn, Frank (2010). Marcus Aurelius: A Life. Da Capo Press. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-306-81916-2.

- ↑ McLynn, Frank (2010). Marcus Aurelius: A Life. Da Capo Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-306-81916-2.

- 1 2 Mócsy, András (Apr 8, 2014). Pannonia and Upper Moesia (Routledge Revivals): A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. Routledge. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-317-75425-1.

- ↑ Mócsy, András (Apr 8, 2014). Pannonia and Upper Moesia (Routledge Revivals): A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. Routledge. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-317-75425-1.

- ↑ Mócsy, András (Apr 8, 2014). Pannonia and Upper Moesia (Routledge Revivals): A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. Routledge. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-317-75425-1.

- ↑ Grumeza, Ion (2009). Dacia: Land of Transylvania, Cornerstone of Ancient Eastern Europe. Lanham: Hamilton Books. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-7618-4466-2.

- ↑ Mócsy, András (Apr 8, 2014). Pannonia and Upper Moesia (Routledge Revivals): A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. Routledge. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-317-75425-1.

- 1 2 Mócsy, András (Apr 8, 2014). Pannonia and Upper Moesia (Routledge Revivals): A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. Routledge. p. 189. ISBN 978-1-317-75425-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mócsy, András (Apr 8, 2014). Pannonia and Upper Moesia (Routledge Revivals): A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. Routledge. p. 190. ISBN 978-1-317-75425-1.

- ↑ Beckmann, Martin (2011). Column of Marcus Aurelius the Genesis and Meaning of a Roman Imperial Monument. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-8078-7777-7.

- ↑ Bunson, Matthew (2002). Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. New York: Facts On File. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-4381-1027-1.

- ↑ McLynn, Frank (2010). Marcus Aurelius: A Life. Da Capo Press. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-306-81916-2.

- ↑ McLynn, Frank (2010). Marcus Aurelius: A Life. Da Capo Press. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-306-81916-2.

- ↑ Mócsy, András (Apr 8, 2014). Pannonia and Upper Moesia (Routledge Revivals): A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. Routledge. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-317-75425-1.

- ↑ McLynn, Frank (2010). Marcus Aurelius: A Life. Da Capo Press. p. 423. ISBN 978-0-306-81916-2.

- ↑ Malcor, Linda A.; Littleton, C. Scott (2013). From Scythia to Camelot A Radical Reassessment of the Legends of King Arthur, the Knights of the Round Table, and the Holy Grail. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. xxxiv. ISBN 978-1-317-77771-7.

- ↑ McLaughlin, Raoul (2016). The Roman Empire and the Silk Routes: The Ancient World Economy and the Empires of Parthia, Central Asia and Han China. Casemate Publishers. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-4738-8982-8.

- ↑ "Sarmatia". www.everything2.com. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- 1 2 Gordon, Bruce R. "Nomads of the Steppe". web.raex.com. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ↑ "The Migration of Nations and the Arrival of the Slavs in Slovakia". Angelfire. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ↑ Miron Constantinescu; Ștefan Pascu; Petre Diaconu (1975). Relations Between the Autochthonous Population and the Migratory Populations on the Territory of Romania: A Collection of Studies. Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România. p. 65.

- ↑ Ovid (1893) [c. 8 a.d.]. Sidney George Owen, ed. Ovid: Tristia Book III (2nd, rev. ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 60.

Further reading

- Bennett, Julian. (1997). Trajan: Optimus Princeps, Indianapolis University Press, Bloomington.

- Birley, Anthony. (1987). Marcus Aurelius: A Biography, Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Bunson, Matthew. (1994). Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire, Facts on File Inc., NY.

- Christian, David. (1999). A History of Russia, Mongolia and Central Asia, Vol. 1. Blackwell.

- Harry Thurston Peck. (1898). Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, New York. Harper and Brothers.

- Kerr, William George. (1995). A Chronological Study of the Marcomannic Wars of Marcus Aurelius, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Kristó, Gyula. (1998). Magyarország története – 895–1301 (The History of Hungary – From 895 to 1301, Budapest: Osiris. p. 316. ISBN 963-379-442-0.

- Macartney, C.A. (1962). Hungary: A Short History, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh.

- Maenchen-Helfen, J. Otto. (1973). The World of the Huns, University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Strayer, Joseph R., editor in chief. (1987). A Dictionary of the Middle Ages, Charles Scribner's Sons, NY.

-

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Iazyges". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Iazyges". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iazyges. |

- Gordon, Bruce R. "Nomads of the Steppe". web.raex.com. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "Sarmatia". www.everything2.com. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

.jpeg.png)