Bactrian language

| Bactrian | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Bactria |

| Region | Afghanistan, Central Asia |

| Era | 300 BC – 1000 AD[1] |

|

Indo-European

| |

|

Greek script Manichaean script | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

Kushan Empire Hephthalite Empire |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

xbc |

Linguist list |

xbc |

| Glottolog |

bact1239[2] |

Bactrian (Αρια, Arya) is an Iranian language which was spoken in the Central Asian region of Bactria (present-day Afghanistan and Tajikistan), and used as the official language of the Kushan and the Hephthalite empires.

Etymology

It was long thought that Avestan represented "Old Bactrian", but this notion had "rightly fallen into discredit by the end of the 19th century".[3]

Bactrian, which was written predominantly in an alphabet based on the Greek script, was known natively as αρια ("Arya"; an endonym common amongst Iranian peoples). It has also been known by names such as Greco-Bactrian, Kushan or Kushano-Bactrian.

Under Kushan rule, Bactria became known as Tukhara or Tokhara, and later as Tokharistan. When texts in two extinct and previously unknown Indo-European languages were discovered in the Tarim Basin of China, during the early 20th Century, they were linked circumstantially to Tokharistan, and Bactrian was sometimes referred to as "Eteo-Tocharian" (i.e. "true" or "original" Tocharian). By the 1970s, however, it became clear that there was little evidence for such a connection. For instance, the Tarim "Tocharian" languages were part of the so-called "centum group" within the Indo-European family, and were most closely related to the Anatolian languages, whereas Bactrian was a satemised Iranian language.

Classification

Bactrian is a part of the Eastern Iranian areal group, and shares features with the extinct Middle Iranian languages Sogdian and Khwarezmian (Eastern) and Parthian (Western), as well as to the modern Eastern Iranian languages Pashto, Yidgha, and Munji.[4] Its genealogical position is unclear.[5]

History

Following the conquest of Bactria by Alexander the Great in 323 BC, for about two centuries Greek was the administrative language of his Hellenistic successors, that is, the Seleucid and the Greco-Bactrian kingdoms. Eastern Scythian tribes (the Saka, or Sacaraucae of Greek sources) invaded the territory around 140 BC, and at some time after 124 BC, Bactria was overrun by Yuezhi Tocharian tribes. Subsequently, one of the Yuezhi tribes advanced to found the Kushan dynasty in the 1st century AD.

The Kushans at first retained the Greek language for administrative purposes, but soon began to use Bactrian. The Bactrian Rabatak inscription (discovered in 1993 and deciphered in 2000) records that the Kushan king Kanishka (c. 127 AD)[6][7] discarded Greek (Ionian) as the language of administration and adopted Bactrian ("Arya language"). The Greek language accordingly vanishes from official use and only Bactrian is attested. The use of the Greek script however remained to write Bactrian.

In the 3rd century, the Kushan territories west of the Indus river fell to the Sassanids, and Bactrian began to be influenced by Middle Persian. Next to Pahlavi script and (occasionally) Brahmi script, some coinage of this period is still in Greco-Bactrian script. Beginning in the mid-4th century, Bactria and northwestern India yielded to the Hephthalite tribes. The Hephthalite period is marked by linguistic diversity and in addition to Bactrian, Middle Persian, North Indo-Aryan, Turkish and Latin vocabulary is also attested. The Hephthalites ruled their territories until the 7th century when they were overrun by the Arabs, after which the official use of Bactrian ceased. Although Bactrian briefly survived in other usage, that too eventually ceased, and the latest examples of the language date to the end of the 9th century.[8]

The territorial expansion of the Kushans helped propagate Bactrian to Northern India and parts of Central Asia.

Writing system

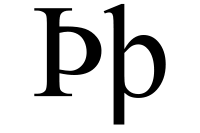

Among Indo-Iranian languages, the use of the Greek script is unique to Bactrian. Although ambiguities remain, some of the disadvantages were overcome by using heta (Ͱ, ͱ) for /h/ and by introducing sho (Ϸ, ϸ) to represent /ʃ/. Xi (Ξ, ξ) and psi (Ψ, ψ) were not used for writing Bactrian as the ks and ps sequences do not occur in Bactrian. They were however probably used to represent numbers (just as other Greek letters were).

Records

The Bactrian language is known from inscriptions, coins, seals, manuscripts, and other documents.

Sites at which Bactrian language inscriptions have been found are (in North-South order) Afrasiab in Uzbekistan; Kara-Tepe, Airtam, Delbarjin, Balkh, Kunduz, Baglan, Ratabak/Surkh Kotal, Oruzgan, Kabul, Dasht-e Navur, Ghazni, Jagatu in Afghanistan; and Islamabad, Shatial Bridge and Tochi Valley in Pakistan. Of eight known manuscript fragments in Greco-Bactrian script, one is from Lou-lan and seven from Toyoq, where they were discovered by the second and third Turpan expeditions under Albert von Le Coq. One of these may be a Buddhist text. One other manuscript, in Manichaean script, was found at Qočo by Mary Boyce in 1958.

Over 150 legal documents, accounts, letters and Buddhist texts have surfaced since the 1990s, several of them currently a part of the collection of Nasser Khalili. These have greatly increased the detail in which Bactrian is currently known.

Phonology

The phonology of Bactrian is not known with certainty, due to the limitations of the native scripts.

Consonants

| Type | Labial | Dental or alveolar |

Palatal or postalveolar |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labialized | ||||||

| Stops | Voiceless | п [p] | τ [t] | κ [k] | |||

| Voiced | β, ββ [b]? | δ, δδ [d] | γ [g] | ||||

| Affricates | Voiceless | σ [t͡s] | |||||

| Voiced | ζ [d͡z] | ||||||

| Fricatives | Voiceless | φ [f] | θ [θ]?, σ [s] | ϸ [ʃ] | χ [x] | χο [xʷ] | υ [h] |

| Voiced | β [v] | δ [ð]?, ζ [z] | ζ [ʒ]? | γ [ɣ] | |||

| Nasals | μ [m] | ν [n] | |||||

| Approximants | λ [l] | ι [j] | ο [w] | ||||

| Rhotic | ρ [r] | ||||||

A major difficulty in determining Bactrian phonology is that affricates and voiced stops were not consistently distinguished from the corresponding fricatives in the Greek script.

- Proto-Iranian *b, *d, *g have generally become spirants, as in most other Eastern Iranian languages. A distinctive feature of Bactrian, shared within the Iranian languages with Munji, Yidgha and Pashto, is the development of Proto-Iranian *d > *ð further to /l/, which may have been areal in nature.[5] Original *d remains only in a few consonant clusters, e.g. *bandaka > βανδαγο 'servant', *dugdā > λογδο 'daughter'. The clusters /lr/ and /rl/ appear in earlier Bactrian, but revert to /dr/, /rd/ later, e.g. *drauga > λρωγο (4th to 5th century) > δδρωρο (7th to 8th century) 'lie, falsehood'.[9]

- Proto-Iranian *p, *t, *č, *k have become voiced between vowels, and after a nasal consonant or *r.

- Inside a word, the digraphs ββ, δδ for original voiceless *p, *t can be found, which probably represent [b], [d]. The former is attested only in a single word, αββο 'water'. Manichaean Bactrian appears to only have had /v/ in native vocabulary. According to Gholami, instances of single δ may indicate a fricative pronunciation, [ð].[10]

- γ appears to stand for both the stop [g] and the fricative [ɣ], but it is unclear if a contrast existed, and which instances are which. Evidence from the Manichaean script suggests that γ from *k may have been /g/ and γ from *g may have been /ɣ/. According to Greek orthographic practices, γγ represents [ŋg].[11]

- σ may continue both Proto-Iranian *c > *s and *č, and the Manichaean script confirms that it represents two phonemes, likely /s/ and /ts/.[12]

- ζ may continue similarly on one hand Proto-Iranian *dz > *z, and on the other *ǰ and *č, and it represents at least /z/ and /dz/. This distinction is again confirmed by the Manichaean script. Also a third counterpart of ζ is found in Manichaean Bactrian, possibly representing /ʒ/.

The status of θ is unclear; it only appears in the word ιθαο 'thus, also', which may be a loanword from another Iranian language. In most positions Proto-Iranian *θ becomes /h/ (written υ), or is lost, e.g. *puθra- > πουρο 'son'.[13] The cluster *θw, however, appears to become /lf/, e.g. *wikāθwan > οιγαλφο 'witness'.[14]

ϸ continues, in addition to Proto-Iranian *š, also Proto-Iranian *s in the clusters *sr, *str, *rst. In several cases Proto-Iranian *š however becomes /h/ or is lost; the distribution is unclear. E.g. *snušā > ασνωυο 'daughter-in-law', *aštā > αταο 'eight', *xšāθriya > χαρο 'ruler', *pašman- > παμανο 'wool'.

Vowels

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Greek script does not consistently represent vowel length. Fewer vowel contrasts yet are found in the Manichaean script, but short /a/ and long /aː/ are distinguished in it, suggesting that Bactrian generally retains the Proto-Iranian vowel length contrast.

It is not clear if ο might represent short [o] in addition to [u], and if any contrast existed. Short [o] may have occurred at least as a reflex of *a followed by a lost *u in the next syllable, e.g. *madu > μολο 'wine', *pasu > ποσο 'sheep'. Short [e] is also rare. By contrast, long /eː/, /oː/ are well established as reflexes of Proto-Iranian diphthongs and certain vowel-semivowel sequences: η < *ai, *aya, *iya; ω < *au, *awa.

An epenthetic vowel [ə] (written α) is inserted before word-initial consonant clusters.

Original word-final vowels and word-initial vowels in open syllables were generally lost. A word-final ο is normally written, but this was probably silent, and it is appended even after retained word-final vowels: e.g. *aštā > αταο 'eight', likely pronounced /ataː/.

The Proto-Iranian syllabic rhotic *r̥ is lost in Bactrian, and is reflected as ορ adjacent to labial consonants, ιρ elsewhere; this agrees with the development in the western Iranian languages Parthian and Middle Persian.

Footnotes

- ↑ Bactrian at MultiTree on the Linguist List

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Bactrian". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Gershevitch 1983, p. 1250

- ↑ Henning (1960), p. 47. Bactrian thus “occupies an intermediary position between Pashto and Yidgha-Munji on the one hand, Sogdian, Choresmian, and Parthian on the other: it is thus in its natural and rightful place in Bactria”.

- 1 2 Novák, Ľubomir (2014). "Question of (re)classification of Eastern Iranian languages". Linguistica Brunensia: 77–87.

- ↑ Harry Falk (2001), “The yuga of Sphujiddhvaja and the era of the Kuṣâṇas.” Silk Road Art and Archaeology 7: 121–36.p. 133.

- ↑ http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/newsletter/vol10/SilkRoad_10_2012_simswilliams.pdf

- ↑ History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 B. C. to A, Part 250 (illustrated ed.). UNESCO. 1994. p. 433. ISBN 9231028464. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ↑ Gholami 2010, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Gholami 2010, p. 10.

- ↑ Gholami 2010, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Gholami 2010, p. 12.

- ↑ Gholami 2010, p. 13.

- ↑ Gholami 2010, p. 25.

References

- Falk (2001): “The yuga of Sphujiddhvaja and the era of the Kuṣâṇas.” Harry Falk. Silk Road Art and Archaeology VII, pp. 121–136.

- Henning (1960): “The Bactrian Inscription.” W. B. Henning. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 23, No. 1. (1960), pp. 47–55.

- Gershevitch, Ilya (1983), "Bactrian Literature", in Yarshater, Ehsan, Cambridge History of Iran, 3 (2), Cambridge: Cambridge UP, pp. 1250–1258, ISBN 0-511-46773-7.

- Gholami, Saloumeh (2010), Selected Features of Bactrian Grammar (pdf) (PhD thesis), University of Göttingen

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas (1989), "Bactrian Language", Encyclopedia Iranica, 3, New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 344–349.

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas (1989), "Bactrian", in Schmitt, Rüdiger, Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum, Wiesbaden: Reichert, pp. 230–235.

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas (1997), New Findings in Ancient Afghanistan: the Bactrian documents discovered from the Northern Hindu-Kush, [lecture transcript], Tokyo: Department of Linguistics, University of Tokyo