Tai languages

| Tai | |

|---|---|

| Zhuang–Thai | |

| Geographic distribution: | Southern China (esp. Guangxi, Guizhou, Yunnan and Guangdong), Southeast Asia |

| Linguistic classification: |

|

| Proto-language: | Proto-Tai |

| Subdivisions: |

|

| ISO 639-2 / 5: | tai |

| Glottolog: | daic1237[1] |

|

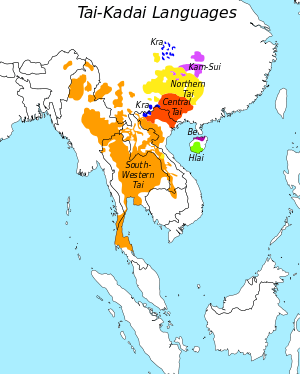

Distribution of the Tai–Kadai language family. The Tai languages are: Northern Tai / Northern Zhuang

Central Tai / Southern Zhuang

Southwestern Tai / Thai | |

The Tai or Zhuang–Tai[2] languages (Thai: ภาษาไท or ภาษาไต, transliteration: p̣hās̛̄āthay or p̣hās̛̄ātay) are a branch of the Tai–Kadai language family. The Tai languages include the most widely spoken of the Tai–Kadai languages, including standard Thai or Siamese, the national language of Thailand; Lao or Laotian, the national language of Laos; Burma's Shan language; and Zhuang, a major language in the southern Chinese province of Guangxi.

Name

Cognates with the name Tai (Thai, Dai, etc.) are used by speakers of many Tai languages. The term Tai is now well-established as the generic name in English. In his book The Tai-Kadai Languages Anthony Diller claims that Lao scholars he has met are not pleased with Lao being regarded as a Tai language.[3] For some, Thai should instead be considered a member of the Lao language family.[3] One or more Ancient Chinese characters for ‘Lao’ may be cited in support of this alternative appellation.[3] Some scholars including Benedict (1975), have used Thai to refer to a wider (Tai) grouping and one sees designations like proto-Thai and Austro-Thai in earlier works.[3] In the institutional context in Thailand, and occasionally elsewhere, sometimes Tai (and its corresponding Thai-script spelling, without a final -y symbol) is used to indicate varieties in the language family not spoken in Thailand or spoken there only as the result of recent immigration.[3] In this usage Thai would not then be considered a Tai language.[3] On the other hand, Gedney, Li and others have preferred to call the standard language of Thailand Siamese rather than Thai, perhaps to reduce potential Thai/Tai confusion, especially among English speakers not comfortable with making a non-English initial unaspirated voiceless initial sound for Tai, which in any event might sound artificial or arcane to outsiders.

According to Michel Ferlus, the ethnonyms Tai/Thai (or Tay/Thay) would have evolved from the etymon *k(ə)ri: 'human being' through the following chain: kəri: > kəli: > kədi:/kədaj (-l- > -d- shift in tense sesquisyllables and probable diphthongization of -i: > -aj).[4][5] This in turn changed to di:/daj (presyllabic truncation and probable diphthongization -i: > -aj). And then to *dajA (Proto-Southwestern Tai) > tʰajA2 (in Siamese and Lao) or > tajA2 (in the other Southwestern and Central Tai languages by Li Fangkuei). Michel Ferlus' work is based on some simple rules of phonetic change observable in the Sinosphere and studied for the most part by William H. Baxter (1992).[5]

Many of the languages are called Zhuang in China and Nung in Vietnam.

History

Citing the fact that both the Zhuang and Thai peoples have the same exonym for the Vietnamese, kɛɛuA1,[6] Jerold A. Edmondson of the University of Texas, Arlington posited that the split between Zhuang (a Central Tai language) and the Southwest Tai languages happened no earlier than the founding of Jiaozhi in Vietnam in 112 BCE but no later than the 5th–6th century.[7] However, based on layers of Chinese loanwords in Proto-Southwestern Tai and other historical evidence, Pittayawat Pittayaporn (2014) suggests that the separation between Proto-Southwestern Tai and Proto-Tai must have taken place sometime between the 8th–10th centuries.[8]

Internal classification

Haudricourt (1956)

Haudricourt[9] emphasizes the specificity of Dioi (Zhuang) and proposes to make a two-way distinction between the following two sets. The language names used in Haudricourt's (1956) original are provided first, followed by currently more widespread ethnonyms in brackets.

| Tai |

| ||||||

| |

Characteristics of the Dioi group pointed out by Haudricourt are (i) a correspondence between r- in Dioi and the lateral l- in the other Tai languages, (ii) divergent characteristics of the vowel systems of the Dioi group: e.g. 'tail' has a /a/ vowel in Tai proper, as against /ə̄/ in Bo-ai, /iə/ in Tianzhou, and /ɯə/ in Tianzhou and Wuming, and (iii) the lack, in the Dioi group, of aspirated stops and affricates, which are found everywhere in Tai proper.

As compared with Li Fang-kuei's classification, Haudricourt's classification amounts to consider Li's Southern Tai and Central Tai as forming a subgroup, of which Southwestern Tai is a sister: the three last languages in Haudricourt's list of 'Tai proper' languages are Tho (Tày), Longzhou, and Nung, which Li classifies as 'Central Tai'.

| Tai |

| ||||||||||||

| |

Li (1977)

Li Fang-Kuei divided Tai into Northern, Central, and Southwestern (Thai) branches. However, Central Tai does not appear to be a valid group. Li (1977) proposes a tripartite division of Tai into three sister branches. This classification scheme has long been accepted as the standard one in the field of comparative Tai linguistics.

| Tai |

| |||||||||

| |

Gedney (1989)

Gedney (1989) considers Central and Southwestern Tai to form a subgroup, of which Northern Tai is a sister.

| Tai |

| ||||||||||||

| |

Pittayaporn (2009)

Overview

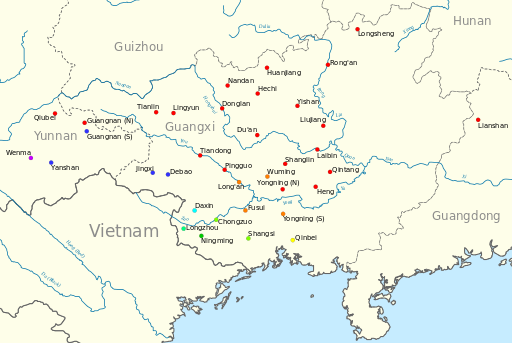

In a 2009 Ph.D. dissertation, Pittayawat Pittayaporn classifies the Tai languages based on clusters of shared innovations (which, individually, may be associated with more than one branch) (Pittayaporn 2009:298). In Pittayaporn's classification system, the Zhuang dialects of Chóngzuǒ in Guangxi have the most internal diversity. Only the Southwestern Tai branch remains unchanged from Fang-Kuei Li's 1977 classification system, and several of the Southern Zhuang languages allocated ISO codes are shown to be paraphyletic. The classification is as follows:[10]

| Tai |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Standard Zhuang is based on the dialect of Shuangqiao (双桥), Wuming County.

Sound changes

The following phonological shifts occurred in the Q (Southwestern), N (Northern), B (Ningming), and C (Chongzuo) subgroups (Pittayaporn 2009:300–301).

| Proto-Tai | Subgroup Q[11] | Subgroup N[12] | Subgroup B | Subgroup C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| *ɤj, *ɤw, *ɤɰ | *aj, *aw, *aɰ | *i:, *u:, *ɯ: | *i:, *u:, *ɯ: | – |

| *ɯj, *ɯw | *i:, *u:[13] | *aj, *aw[14] | *i:, *u: | – |

| *we, *wo | *e:, *o: | *i:, *u: | *e:, *o:[15] | *e:, *o:[16] |

| *ɟm̩.r- | *br- | *ɟr- | – | *ɟr- |

| *k.t- | – | *tr- | – | *tr- |

| *ɤn, *ɤt, *ɤc | – | *an, *at, *ac[17] | – | – |

Furthermore, the following shifts occurred at various nodes leading up to node Q.

- E: *p.t- > *p.r-; *ɯm > *ɤm

- G: *k.r- > *qr-

- K: *e:, *o: > *ɛ:, *ɔ:

- O: *ɤn > *on

- Q: *kr- > *ʰr-

Reconstruction

Proto-Tai has been reconstructed in 1977 by Fang-Kuei Li and by Pittayawat Pittayaporn in 2009.[18]

Proto-Southwestern Tai has also been reconstructed in 1977 by Fang-Kuei Li and by Nanna L. Jonsson in 1991.[19]

| Proto-Tai | Thai script | ||

| 1st | singular | *ku | กู |

| dual (exclusive) | *pʰɯa | เผือ | |

| plural (exclusive) | *tu | ตู | |

| Incl. | dual (inclusive) | *ra | รา |

| plural (inclusive) | *rau | เรา | |

| 2nd | singular | *mɯŋ | มึง |

| dual | *kʰɯa | เขือ | |

| plural | *su | สู | |

| 3rd | singular | *man | มัน |

| dual | *kʰa | ขา | |

| plural | *kʰau | เขา |

Comparison

Below is comparative table of Tai languages.

| English | Proto-Southwestern Tai[20] | Thai | Lao | Lanna | Shan | Tai Lü | Standard Zhuang |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wind | *lom | /lōm/ | /lóm/ | /lōm/ | /lóm/ | /lôm/ | /ɣum˧˩/ |

| town | *mɯaŋ | /mɯ̄aŋ/ | /mɯ́aŋ/ | /mɯ̄aŋ/ | /mɤ́ŋ/ | /mɤ̂ŋ/ | /mɯŋ˧/ |

| earth | *ʔdin | /dīn/ | /dìn/ | /dīn/ | /lǐn/ | /dín/ | /dei˧/ |

| fire | *vai/aɯ | /fāj/ | /fáj/ | /fāj/ | /pʰáj/ or /fáj/ | /fâj/ | /fei˧˩/ |

| heart | *čai/aɯ | /hǔa tɕāj/ | /hǔa tɕàj/ | /hǔa tɕǎj/ | /hǒ tsǎɰ/ | /hó tɕáj/ | /sim/ |

| love | *rak | /rák/ | /hāk/ | /hák/ | /hâk/ | /hak/ | /gyai˧˩/ |

| water | *naam | /náːm/ | /nâm/ | /nám/ | /nâm/ | /nà̄m/ | /ɣaem˦˨/ |

Writing systems

Many Southwestern Tai languages are written using Brāhmī-derived alphabets. Zhuang languages are traditionally written with Chinese characters called Sawndip, and now officially written with a romanized alphabet, though the traditional writing system is still in use to this day.

- Thai alphabet

- Lao alphabet

- Sawndip

- Shan alphabet

- Ahom alphabet

- Tai Dam alphabet

- Tai Le alphabet

- New Tai Lue alphabet

- Tai Tham alphabet

See also

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Daic". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Diller, 2008. The Tai–Kadai Languages.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Diller, Anthony; Edmondson, Jerry; Luo, Yongxian (2004). The Tai-Kadai Languages. Routledge (2004), pp. 5-6. ISBN 1135791163.

- ↑ Ferlus, Michel (2009). Formation of Ethnonyms in Southeast Asia. 42nd International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics, Nov 2009, Chiang Mai, Thailand. 2009, p.3.

- 1 2 Pain, Frédéric (2008). An Introduction to Thai Ethnonymy: Examples from Shan and Northern Thai. Journal of the American Oriental Society Vol. 128, No. 4 (Oct. - Dec., 2008), p.646.

- ↑ A1 designates a tone.

- ↑ Edmondson, Jerold A. The power of language over the past: Tai settlement and Tai linguistics in southern China and northern Vietnam. Studies in Southeast Asian languages and linguistics, Jimmy G. Harris, Somsonge Burusphat and James E. Harris, ed. Bangkok, Thailand: Ek Phim Thai Co. Ltd. http://ling.uta.edu/~jerry/pol.pdf (see page 15)

- ↑ Pittayaporn, Pittayawat (2014). Layers of Chinese Loanwords in Proto-Southwestern Tai as Evidence for the Dating of the Spread of Southwestern Tai. MANUSYA: Journal of Humanities, Special Issue No 20: 47–64.

- ↑ Haudricourt, André-Georges. 1956. De la restitution des initiales dans les langues monosyllabiques : le problème du thai commun. Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris 52. 307–322.

- ↑ Pittayaporn, Pittayawat. 2009. The Phonology of Proto-Tai. Ph.D. dissertation. Department of Linguistics, Cornell University.

- ↑ Unless indicated otherwise, all phonological shifts occurred at the primary level (node A).

- ↑ Unless indicated otherwise, all phonological shifts occurred at the primary level (node D).

- ↑ Also, the *ɯ:k > *u:k shift occurred at node A.

- ↑ Innovation at node N

- ↑ For node B, the affected Proto-Tai syllable was *we:, *wo:.

- ↑ For node C, the affected Proto-Tai syllable was *we:, *wo:.

- ↑ Innovation at node J

- ↑ http://language.psy.auckland.ac.nz/austronesian/language.php?id=698

- ↑ http://language.psy.auckland.ac.nz/austronesian/language.php?id=684

- ↑ Thai Lexicography Resources

Further reading

- Brown, J. Marvin. From Ancient Thai to Modern Dialects. Bangkok: Social Science Association Press of Thailand, 1965.

- Chamberlain, James R. A New Look at the Classification of the Tai Languages. [s.l: s.n, 1972.

- Conference on Tai Phonetics and Phonology, Jimmy G. Harris, and Richard B. Noss. Tai Phonetics and Phonology. [Bangkok: Central Institute of English Language, Office of State Universities, Faculty of Science, Mahidol University, 1972.

- Diffloth, Gérard. An Appraisal of Benedict's Views on Austroasiatic and Austro-Thai Relations. Kyoto: Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University, 1976.

- Đoàn, Thiện Thuật. Tay-Nung Language in the North Vietnam. [Tokyo?]: Instttute [sic] for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, 1996.

- Gedney, William J. On the Thai Evidence for Austro-Thai. [S.l: s.n, 1976.

- Gedney, William J., and Robert J. Bickner. Selected Papers on Comparative Tai Studies. Michigan papers on South and Southeast Asia, no. 29. Ann Arbor, Mich., USA: Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan, 1989. ISBN 0-89148-037-4

- Gedney, William J., Carol J. Compton, and John F. Hartmann. Papers on Tai Languages, Linguistics, and Literatures: In Honor of William J. Gedney on His 77th Birthday. Monograph series on Southeast Asia. [De Kalb]: Northern Illinois University, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, 1992. ISBN 1-877979-16-3

- Gedney, William J., and Thomas J. Hudak. (1995). William J. Gedney's central Tai dialects: glossaries, texts, and translations. Michigan papers on South and Southeast Asia, no. 43. Ann Arbor, Mich: Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan ISBN 0-89148-075-7

- Gedney, William J., and Thomas J. Hudak. William J. Gedney's the Yay Language: Glossary, Texts, and Translations. Michigan papers on South and Southeast Asia, no. 38. Ann Arbor, Mich: Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan, 1991. ISBN 0-89148-066-8

- Gedney, William J., and Thomas J. Hudak. William J. Gedney's Southwestern Tai Dialects: Glossaries, Texts and Translations. Michigan papers on South and Southeast Asia, no. 42. [Ann Arbor, Mich.]: Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan, 1994. ISBN 0-89148-074-9

- Hudak, Thomas John. William J. Gedney's The Tai Dialect of Lungming: Glossary, Texts, and Translations. Michigan papers on South and Southeast Asia, no. 39. [Ann Arbor]: Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan, 1991. ISBN 0-89148-067-6

- Li, Fang-kuei. 1977. Handbook of Comparative Tai. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawai’i Press.

- Li, Fang-kuei. The Tai Dialect of Lungchow; Texts, Translations, and Glossary. Shanghai: Commercial Press, 1940.

- Østmoe, Arne. A Germanic-Tai Linguistic Puzzle. Sino-Platonic papers, no. 64. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Dept. of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Pennsylvania, 1995.

- Sathāban Sūn Phāsā Qangkrit. Bibliography of Tai Language Studies. [Bangkok]: Indigenous Languages of Thailand Research Project, Central Institute of English Language, Office of State Universities, 1977.

- Shorto, H. L. Bibliographies of Mon–Khmer and Tai Linguistics. London oriental bibliographies, v. 2. London: Oxford University Press, 1963.

- Tingsabadh, Kalaya and Arthur S. Abramson. Essays in Tai Linguistics. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University Press, 2001. ISBN 974-347-222-3

External links

- SEAlang Library

- Comparative Tai–Kadai Swadesh vocabulary lists (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- ABVD: Proto-Tai word list

- ABVD: Proto-Southwestern Tai word list

- http://www.academia.edu/3659357/Tai_Words_and_the_Place_of_the_Tai_in_the_Vietnamese_Past