Baluan-Pam language

| Baluan-Pam | |

|---|---|

| Paluai, Pam | |

| Native to | Papua New Guinea |

| Region | Baluan Island and Pam Islands, Manus Province |

Native speakers | 2,000 (2000)[1] |

|

Austronesian

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

blq |

| Glottolog |

balu1257[2] |

Baluan-Pam is an Oceanic language of Manus Province, Papua New Guinea. It is spoken on Baluan Island and on nearby Pam Island. The number of speakers, according to the latest estimate based on the 2000 Census, is 2,000. Speakers on Baluan Island prefer to refer to their language with its native name Paluai.

The language is of the agglutinating type with comparatively little productive morphology. Basic constituent order is SVO.

Varieties and related languages

The Baluan Island and Pam Island varieties of the language are practically similar, apart from a number of lexical differences. The language is closely related to Lou, spoken on Lou Island. Lou forms a dialect chain, with the varieties spoken on the far side of the island, facing Manus mainland, differing the most from Paluai and the ones on the side facing Baluan Island being the closest.

In Manus Province, about 32 languages are spoken, all of which belong to the Admiralties branch, a higher-order subgroup of Oceanic, which belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of Austronesian. Most of the languages of Manus Province are scarcely documented. A reference grammar of Loniu was published in 1994.[3]

There is a minority of Titan speakers on Baluan, relatively recent immigrants living in Mouk village. The Titan people have become well known through the work of Margaret Mead. Many speakers have at least a passive command of Titan and Lou. In addition, the creole language Tok Pisin is widely spoken on the island, and most people have at least a basic command of English.

Phonology

Consonant phonemes

The table below shows the consonant phonemes in the language.

| Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | mʷ | n | ŋ | |

| Plosive | p | pʷ | t | k | (kʷ) |

| Fricative | s | (h) | |||

| Approximant | l | (j) | (w) | ||

| Vibrant | (ɾ~r) | ||||

In contrast to many of the Manus languages, there are no bilabial trill or prenasalised consonants. The consonant inventory is rather simple, with a labialised nasal and plosive in addition to bilabial, apico-alveolar and dorso-velar stops and nasals. There is just one fricative, /s/, with /h/ being a very marginal phoneme. /t/ has a tap or trill as a variant. The glides [j] and [w] are analysed as non-syllabic variants of /i/ and /u/, respectively.[4]

Vowel phonemes

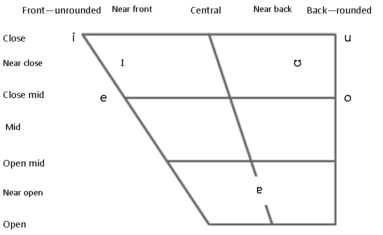

The figure below shows the vowel phonemes in the language.

The vowel inventory consists of the standard five vowels most common in Oceanic languages,[5] with two additions: a near-front unrounded high vowel and a near-back round high vowel.

Syllable structure

The syllable template is (C)V(C). Not many syllables start with a vowel. Due to loss of word-final consonants and consequently vowels, which is a feature of eastern Admiralties languages,[6] the language allows consonants in the syllable coda and has many monosyllabic words with CVC form.

Word classes

Open classes

The two major open word classes are noun and verb (with a major subclass of stative verbs), with adjectives and adverbs as minor classes distinguished from both noun and verb and from each other. Verb to noun and verb to adjective derivations are very common, but not vice versa. Most predicates are headed by a verb complex, but nouns, adjectives, numerals and some prepositions can also function as predicate head. Only verbs, however, can take bound pronouns and be modified by TAM particles.

Closed classes

The major closed classes in the language, containing function words, are pronouns, demonstratives, prepositions, numerals, quantifiers, and interrogative words. The pronominal system distinguishes singular, dual, paucal and plural number and first, second and third person, but not gender. The range of adpositional forms is limited, since most spatial relations are expressed either by a directly possessed spatial noun, or by a serial verb construction containing a directional.

Morphology

Nominal morphology

The language does not have case or number marking on nouns. The only nominal morphology in the language functions to indicate possession. A distinction is made within nominal possessive constructions between direct and indirect possession. This correlates with, but does not coincide completely with, a semantic distinction between inalienable and alienable possession. With direct possession, a suffix indicating person and number of the possessor is added directly to the noun stem. With indirect possession, this suffix is added to a postposed possessive particle ta-. Most kinship terms and body part terms either can or must be used in a direct possessive construction. In addition, spatial nouns, referring to concepts such as "inside", "on top of" and "behind", are obligatorily used in a direct possessive construction.

Verbal morphology

Verbal derivational morphology is limited to the causative prefix pe-, the applicative suffix -ek, and reduplication.

Causative

The causative pe- transitivises an intransitive verb. Causatives can be productively formed, but only with stative verbs. A causative adds an extra "causer" A argument, demoting the original S argument of the intransitive verb to O position. Examples are e.g. mat 'die, be dead' → pemat 'kill'.

Applicative

The applicative in this language is a valency-rearranging rather than a valency-increasing device. It promotes an instrumental Oblique constituent of a verb to O position. The original O is not demoted, but rather follows the promoted constituent as a second object. The applicative is typically encountered in one specific discourse/information structure context. It is used as an anaphorical device to refer back to an item mentioned just before, usually in the previous clause, as in the example below:

- (1) ope lêp suep a ope yilek ponat

- [wo]=pe lêp [suep] a [wo]=pe yil-ek=Ø [ponat]

- 2sg=PFV take hoe and 2sg=PFV dig-APPL=3sg.ZERO soil

- ‘You will take a hoe and you will dig the ground with it.’ [lit. ‘dig-with (it) the ground’]

Reduplication

With transitive verbs, full or partial reduplication can be used as an intransitivising device. With intransitive verbs, reduplication adds aspectual meanings such as continuous aspect. A second function of reduplication within the verb class is to derive nominalizations.

Pronouns

Paradigms

There are four pronominal paradigms: free subject forms, bound subject forms, object forms and possessive forms. They are formally very similar. Pronouns distinguish singular, dual, paucal and plural number, and have a clusivity distinction. Dual refers to two entities, paucal refers to a few (any number between three and about ten), and plural refers to many. Inclusive pronouns include the addressee ("we, including you"), whereas exclusive ones exclude them ("we, but not you"). Below, the paradigm for the free forms is given.

| First person | Second person | Third person | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | wong | wo | yi | |

| Dual | Inclusive | tau | au | u |

| Exclusive | wui | |||

| Paucal | Inclusive | tare | are | ire |

| Exclusive | wure | |||

| Plural | Inclusive | tap | ap | ip |

| Exclusive | ep |

Directional system

Forms in the paradigm

The language has a system of directionals composed of ten members, eight of which are specified with regard to an absolute frame of reference (FoR).[7][8] An absolute FoR is based on fixed bearings, such as where the sun rises or sets or wind directions. In Baluan-Pam the FoR is based on a land-sea axis; a distinction is made between 1) seaward movement, 2) landward movement, and 3) movement parallel to the shore. Therefore, going inland always means going up, and going towards the shore always means going down. In addition, since motion parallel to the shore (i.e. intersecting the land–sea axis) usually means moving on more or less the same level, this has obtained a secondary meaning of ‘moving on a horizontal level’. At sea, the system is extrapolated: thus, for moving towards the shore the same directionals are used as for moving inland, and for moving out to sea the same directionals are used as for moving towards the shore when on land.

The directionals are organised along two dimensions: absolute FoR and deixis. The table below shows the paradigm.

| down, seaward (on land);

out to sea (on water) |

up, landward (on land);

toward the shore (on water) |

parallel to shore | not specified | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| away from deictic centre | suwot | sot | wot | la, lak |

| toward deictic centre | si | sa, sak | - | me |

| not deictically anchored | suwen | sen | wen | - |

The deixis distinction cross-cuts with the FoR distinction, so that five terms are specified for FoR and for deixis, three are specified for FoR only, and two are specified for deixis but not FoR. There is no dedicated term for motion toward the deictic centre parallel to the shore, and no unspecified term that is not deictically anchored (such a term would not add any information to a lexical verb of motion).

Use of directionals

The directional paradigm provides a very precise reference structure with ample use in discourse. For virtually all actions that in some sense involve motion (including perception-based actions such as seeing/looking, speaking or listening), the direction of the action has to be specified with a directional. In Paluai, this is done by a SVC, in which a directional either precedes or follows the main verb. Directional SVCs are a common feature of Oceanic languages.[9][10]

References

- ↑ "Manus Language Map". Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Baluan-Pam". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Hamel, Patricia (1994). A grammar and lexicon of Loniu, Papua New Guinea. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- ↑ Schokkin, Dineke (2014). A grammar of Paluai, the language of Baluan Island, Papua New Guinea. James Cook University: PhD thesis.

- ↑ Lynch, John; Ross, Malcolm; Crowley, Terry (2002). The Oceanic languages. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon.

- ↑ Blust, Robert (2009). The Austronesian languages. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- ↑ Levinson, Stephen C. (2003). Space in language and cognition: explorations in cognitive diversity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Levinson, Stephen C.; Wilkins, David (2006). Grammars of space: explorations in cognitive diversity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Crowley, Terry (2002). Serial verbs in Oceanic: a descriptive typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Durie, M. (1988). "Verb serialization and "verbal-prepositions" in Oceanic languages". Oceanic Linguistics. 27 (1/2): 1–23. doi:10.2307/3623147.