Human givens

The human givens approach is an holistic model of human function and wellbeing. The approach was first developed as an approach to psychotherapy, with the aim to create an model for brief, solution-focused, psychotherapy based on evidence from evolution, anthropology, biology, psychology and sociology.[1] The approach was first outlined in the 1998/9 monograph Psychotherapy, Counselling and the Human Givens (Organising Idea)[2] and amplified in the 2003 book Human Givens: A new approach to emotional health and clear thinking.[3] The human givens organising ideas[4] proffer a description of the nature of human beings, the 'givens' of human genetic heritage and what humans need in order to be happy and healthy.

Human givens approach is grounded in an evolutionary understanding of human nature. It proposes that evolution has endowed all members of our species, regardless of race or culture, with a common set of innate physical and emotional needs along with a set of innate physical, emotional and psychological resources. Like all organisms, humans deploy their 'given' resources in order to meet their 'given' needs in the environment in the course of their daily lives. When innate needs are met in a sufficiently balanced way people will flourish but when this does not happen distress and eventually illness results. The basic human givens proposition is, then, that all emotional distress and mental illness are caused by a failure to get innate needs, particularly emotional needs, met in balance. This may go hand in hand with problems relating to missing, misused or damaged innate resources. The focus of human givens therapy is, therefore, the discovery and rectifying/removal of any impediments to these needs being met in an individual's life. The broader implication of this working hypothesis is that the wellbeing and flourishing (eudaemonia) of humans both individually and collectively is dependent on meeting emotional needs in balance, and the healthy development of psychoemotional resources.

The human givens approach grew out of a psychotherapeutic method - an integrative, bio-psycho-social model of therapy. Within the framework of needs and resources it uses some interventions from known effective therapeutic methods. The organising ideas[4] are new, along with some of the detailed theory (most notably on the function of dreaming), whilst other areas (such as how addictions are created and maintained[5] and the cycle of depression[6]) represents new formulations of existing scientific knowledge.

The human givens approach is not considered by its proponents to be just another model of psychotherapy but rather the beginnings of a unified science of human well-being with ramifications well beyond mental illness.[7] (Just as architects and engineers need to understand the laws of physical nature (such as gravity) in order to design and build successful structures, so anyone working with people needs to understand, and work in harmony with, the laws of human nature if they want their efforts to succeed in the fullest sense.)

The approach could be seen as a practical and easily understood set of tools whereby lives can be made happier, more productive and our future (together with that of the other species with whom we share this planet) made more sustainable. This requires a shared understanding of human innate needs and resources in societies, organisations, communities, professions, families and individuals.

Motivation and purpose

The human givens approach was pioneered because of what was seen as "the primitive stage of development" of the field of psychology, psychotherapy and counselling in which there are an estimated 400+ different models to choose from[8] (which is highly confusing for people seeking effective help). This "state of chaos" was thought to indicate that something was fundamentally wrong with these approaches to understanding human nature, mental illness and how to treat it. In contrast, mature sciences (such as physics and biochemistry) have a common ground of understanding. The human givens approach arose from the perception that such a set of organising ideas[4] was lacking in psychology and psychotherapy.[7][9] It attempts to provide this missing common ground by asking, and suggesting answers to, some fundamental questions:

- Q1: What is a human being?

- A1: A human being is a life form.

- Q2: How is a life form distinct from a non-life form - from an inanimate object such as a stone?

- A2: A life form needs to continually obtain nourishment from its environment in order to maintain itself.

- Q3: How does a life form obtain such nourishment?

- A3: It is born with a set of resources that help it to do this - a ‘guidance system’ that helps it to seek and find appropriate nourishment in the world.

The fundamental, orientating question asked and addressed by the human givens approach is, therefore, "what do we need and how do we go about getting it?" (with the emphasis on we because evidence suggests human beings cannot be truly well in isolation from one another).

Historical background

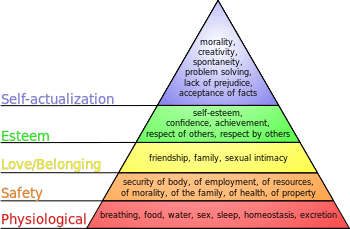

For centuries, wise people and ancient texts have described how humans have innate needs for emotional and spiritual sustenance in addition to physical requirements.[11][12] In more recent times, Abraham Maslow is credited with the first prominent theory which laid out a hierarchy of needs.[13] The precise nature of the hierarchy and the needs have subsequently been refined, and to some extent superseded, by modern neuroscientific and psychological research. Nonetheless, Maslow's key idea has been accepted; that humans have a range of emotional as well as physical needs and that basic needs (e.g. food, shelter, physical safety) need to be met before higher needs (e.g. friendship, achievement) can be satisfied.

Since Maslow's work in the middle of the twentieth century, a significant body of research has been undertaken to clarify what human beings need to be happy and healthy. The UK has contributed significantly to the international effort, through the ground breaking Whitehall Study led by Sir Michael Marmot, which tracked the lifestyles and outcomes for large groups of British civil servants. This identified effects on mental and physical health from emotional needs being met - for instance, it showed that those with less autonomy and control over their lives, or less social support, have worse health outcomes.

In the United States, the work of Martin Seligman, a psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania has been influential. Seligman has summarised the research to date in terms of what makes humans happy; again, this demonstrates themes about universal emotional needs which must be met for people to lead fulfilling lives.[14][15]

At the University of Rochester, contemporaries of Seligman Edward Deci and Richard Ryan have conducted original research and gathered existing evidence to develop a framework of human needs which they call self-determination theory. This states that human beings are born with innate motivations, developed from our evolutionary past. They gather these motivational forces into three groups - autonomy, competence and relatedness. The human givens approach uses a framework of nine needs, which map onto these three groups.

Many more researchers and neuroscientists have contributed to the debate, and over the past twenty years the scientific evidence for these innate emotional needs has become much stronger than it was when Maslow was researching and writing.

Some of the original research demonstrating the evidence for each need is referenced in the following section, but for an accessible summary written in layperson's language the latest version of the core textbook is recommended[16] as is Emotional Intelligence by Daniel Goleman.[17]

Innate needs

Human givens thinking suggests that human beings come into the world with a given set of innate needs, together with innate resources to support them to get those needs met. Physical needs for nutritious food, clean water, air and sleep are obvious, and well understood, because when they are not met people die. However, the emotional needs, which the human givens approach seeks to bring to wider attention, are less obvious, and less well understood, but just as important to human health and even, in some cases, survival. Decades of social and health psychology research now support this.[18]

The human givens approach defines nine emotional needs:

- Security: A sense of safety and security; safe territory; an environment in which people can live without experiencing excessive fear so that they can develop healthily.

- The work of Marmot in the Whitehall Studies, and subsequent interpretation of his data by other researchers, has demonstrated the needs for emotional security to ensure health. A good example is the finding about workers who were subjected to prolonged job security concerns during organisational change processes.[19]

- Autonomy and control: A sense of autonomy and control over what happens around and to us.

- The Whitehall Studies are also an authoritative source to demonstrate that autonomy and control are innate needs. Marmot determined that people who are lower in organisational hierarchies have worse health and mental health outcomes, and that this is because they have less autonomy and control over their working lives.[20] A more technical exposition of how autonomy and control are necessary for human health is given in the Whitehall Study further analysis by Stansfeld, Fuhrer, et al.[21][22]

- Status: A sense of status - being accepted and valued in the various social groups we belong to.

- Privacy: Time and space enough to reflect on and consolidate our experiences.

- Attention: Receiving attention from others, but also giving it; a form of essential nutrition that fuels the development of each individual, family and culture.

- Steve Cole and colleagues have found that "the biological impact of social isolation reaches down into some of our most basic internal processes - the activity of our genes... changes in immune cell gene expression were specifically linked to the subjective experience of social distance.”[23][24] There is also a growing body of research on the damaging effects of solitary confinement on human mental health[25] (although the distress experienced by people in solitary confinement could be said to be due to a combination of unmet needs including those for attention and autonomy/control).

- Connection to the wider community: We have evolved as a group animal and need to feel part of something larger than ourselves.

- Intimacy: Emotional connection to other people - friendship, love, intimacy, fun.

- Competence and achievement: A sense of our own competence and achievements, that we have what it takes to meet life's demands - which ensures we don't feel we are rubbish (don't develop 'low self-esteem').

- Meaning and purpose: A sense of meaning and purpose which comes from being stretched in what we do and how we think - it is through 'stretching' ourselves mentally or physically by service to others, learning new skills or being connected to ideas or philosophies bigger than ourselves that our lives become purposeful and full of meaning. Meaning makes suffering tolerable.

These needs map more or less well to tendencies and motivations described by other psychological evidence, especially that compiled by Deci and Ryan at the University of Rochester.[26][27] The exact categorisation of these needs, however, is not considered important. Needs can be interlinked, and have fuzzy boundaries, as Maslow noted.[28] What matters is a broad understanding of the scope and nature of human emotional needs and why they are so important to our physical and mental health. Humans are a physically vulnerable species that has enjoyed amazing evolutionary success due in large part to its ability to form relationships and communities. Getting the right social and emotional input from others was, in our evolutionary past, literally a matter of life or death. Thus, human givens theory states, people are genetically programmed only to be happy and healthy when these needs are met.

There is evidence that these needs are consistent across cultures, and therefore represent innate human requirements.[29][30][31]

Innate resources

The human givens model also consists of a set of 'resources' (abilities and capabilities) that all human beings are born with, which are used to get the innate needs met. These constitute what is termed an 'inner guidance system'. Learning how to use these resources well is seen as being key to achieving, and sustaining, robust bio-psycho-social health as individuals and as groups (families, communities, societies, cultures etc.).

The given resources include:

- Memory: The ability to develop complex long-term memory, which enables people to add to their innate (instinctive) knowledge and learn;

- Rapport: The ability to build rapport, empathise and connect with other others;

- Imagination: Which enables people to focus attention away from the emotions and problem solve more creatively and objectively (a 'reality simulator');

- Instincts and emotions: A set of basic responses and 'propulsion' for behaviours;

- A rational mind: A conscious, rational mind that can check out emotions, question, analyse and plan;

- A metaphorical mind: The ability to 'know', to understand the world unconsciously through metaphorical pattern matching ('this thing is like that thing');

- An observing self: That part of us which can step back, be more objective and recognise itself as a unique centre of awareness apart from intellect, emotion and conditioning;[32][33]

- A dreaming brain: According to the expectation fulfilment theory of dreaming, this preserves the integrity of our genetic inheritance every night by metaphorically defusing emotionally arousing expectations not acted out during the previous day.

Three reasons for mental illness

A further organising idea[4] proffered by the human givens approach is to suggest that there are three main reasons why individuals may not be getting their needs met and thus why they may become mentally ill:

- Environment: the environment is sick - it is toxic, preventing us from getting, or simply lacking, the things we need;

- Damage: there is damage to our internal guidance system - to our 'hardware' (the brain/body) or 'software' (missing or incomplete instincts and/or unhelpful conditioning);

- Knowledge: we may not know what we need; or we may not have been taught, or may have failed to learn, the coping skills necessary for getting our needs met (for example, to use the imagination for problem solving rather than worrying, or how to make and sustain friendships).

When dealing with mental illness or distress this framework provides a checklist that guides both understanding and treatment.

Key features

Key features of the human givens school include:

- A new model of therapeutic intervention (the APET model) based on the neurological finding that emotion precedes thought.[34][35]

- New insights into trauma and how to treat it effectively - the 'rewind technique'. (The human givens rewind technique has been evaluated in an international textbook on trauma.[36])

- An holistic understanding of the evolutionary origins and function of human dreaming (expectation fulfilment theory of dreaming) which is key to understanding the cycle of depression: how depression develops, is maintained and can be successfully treated.[37]

- A neuroscience-based explanation for addiction and why withdrawal symptoms occur;[38]

- A theory (called 'molar memories') which explains the mechanism that generates and maintains some instances of compulsive behaviour (such as sexual compulsions, anorexia and bulimia);

- A psychobiological explanation of clinical hypnosis, why it works and the mechanisms common to all forms of hypnotic induction;[39]

- New understandings of the autistic spectrum disorder, including what has been termed ‘caetextia’;[40]

- New insights into the nature of psychosis (waking reality processed through the REM state/dreaming brain);[41]

- A clear protocol for conducting therapy sessions - the RIGAAR model: Rapport building; Information gathering; Goal setting (new, positive expectations related to the fulfillment of innate needs); Accessing the client's own strengths and resources (success templates); Agreeing a strategy (for achieving the needs-related goals); Rehearsing success (the enactment of the agreed strategies).

Research and evidence

There are now a number of independent studies evaluating the human givens approach:

- A 12-month evaluation of the human givens approach in primary care (2011): Peer reviewed evidence for the effectiveness of human givens therapy, published in Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, showed that, of 120 patients treated by HG therapists in a GP's surgery, more than three-quarters were either symptom-free or reliably improved as a result of the therapy. This was accomplished in an average of only 3.6 sessions.[42] This compares favourably with the recovery rate for the UK Government’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme, which mainly uses therapists trained in cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) and expects therapy to take longer; less than half of its patients improve or recover.

- Using human givens therapy to support the wellbeing of adolescents (2011): An article for Pastoral Care in Education: An International Journal of Personal, Social and Emotional Development assessed the efficacy of an individual human givens intervention for three young people who reported high anxiety or depression and/or low self-concept. It found positive outcomes for the subjects which provided tentative evidence that human givens therapy might be useful to practitioners delivering therapeutic interventions in schools.[43]

- Assessing the effectiveness of the “human givens” approach in treating depression (2012): A peer-reviewed research paper, published in Mental Health Review Journal found that treating people with mild to moderate depressed mood (measured using HADS) with human givens therapy had quicker results than the treatment provided to people in a control group.[44]

- The Emotional Needs Audit: a report on its reliability and validity (2012): A peer-reviewed research paper published in the Mental Health Review Journal found that the Human Givens Institute’s Emotional Needs Audit (ENA) was a valid and reliable instrument for measuring wellbeing, quality of life and emotional distress. It also concluded that the ENA allows insight into the causes of symptoms, dissatisfaction and distress, complementing standardised tools when used in clinical practice.[45]

- A 5-year evaluation of the human givens therapy using a Practice Research Network (2012): A peer-reviewed research paper published in the Mental Health Review Journal (2012) evaluated five year’s worth of practice-based evidence[46] gleaned from a practice research network. The pre-post treatment effect size suggested that “clients treated using the HG approach experienced relief from psychological distress”.[47]

- Evaluation of human givens ‘rewind’ treatment to treat trauma (2013): A poster presentation for a veteran lead research conference evaluated the effectiveness of a single human givens rewind treatment session to treat PTSD in the general psychiatric population and found that this treatment can be effective with severe, chronic and even multiple traumas in a single session, with some requiring no further treatment.[48]

- Human givens randomised controlled trial: The development of a first randomised-controlled trial (RCT) to test the human givens approach is also in process. The Bristol Randomised Controlled Trial Collaboration (a partnership between the University of Bristol and the National Health Service) has agreed to help design it.

Organisations

The following constitute the main human givens organisations:

Human Givens Institute

The Human Givens Institute is a membership organisation open to those wishing to support and promote the human givens approach through all forms of psychological, educational and social interactions, and the professional body representing the interests of those in the caring and teaching professions who aim to work in alignment with the best scientific knowledge available about the givens of human nature. The Institute is accredited by the Professional Standards Authority for Health and Social Care.[49] for the purposes of regulating practitioners who have completed training as Human Givens Therapists and who are Registered with the Institute.

Human Givens Foundation

The Human Givens Foundation is a charitable organisation devoted to spreading the human givens philosophy and information into organisations concerned with health, education, business, social work and the wider care system, the police, the armed forces, and, more widely, into social policy and government. It aims to support parents, families, couples and individuals to live more harmonious, satisfying and meaningful lives.

Human Givens College

Human Givens College is a training organisation offering psychotherapy courses as well as a full psychotherapy diploma course leading to qualification as a human givens practitioner. There are currently 226 Registered Members on the HGI Register - people who have achieved part 3 of the diploma course and are set up in private practice.

See also

Bibliography of publications

- Griffin, J. & Tyrrell, I. (2013). Human Givens: The New Approach to Emotional Health and Clear Thinking. Human Givens Publishing. ISBN 1-899398-31-7

- Griffin, J. & Tyrrell, I. (2004). How to lift depression fast. Human Givens Publishing. ISBN 1-899398-41-4

- Griffin, J. & Tyrrell, I. (2007). How to master anxiety: Stress, panic attacks, phobias, psychological trauma and more. Human Givens Publishing. ISBN 1-899398-81-3

- Griffin, J. & Tyrrell, I. (2004). Dreaming Reality: How dreaming keeps us sane, or can drive us mad. Human Givens Publishing. ISBN 1-899398-36-8

- Griffin, J. & Tyrrell, I. (2013). Why We Dream: The Definitive Answer. Human Givens Publishing. ISBN 978-1899398423.

- Griffin, J. & Tyrrell, I. (2005). Freedom from addiction: The secret behind successful addiction busting. Human Givens Publishing. ISBN 1-899398-46-5

- Griffin, J. & Tyrrell, I. (2008). Release from anger: Practical help for controlling unreasonable rage. Human Givens Publishing. ISBN 978-1-899398-07-2

- Griffin, J. & Tyrrell, I. (2007). An Idea in Practice: using the human givens approach. Human Givens Publishing. ISBN 978-1-899398-96-6.

- Brown, G. & Winn, D. (2009) How to liberate yourself from pain. Human Givens Publishing. ISBN 978-1-899398-17-1

References

- ↑ "Where did the human givens organising idea come from?".

- ↑ Griffin, Joe; Tyrrell, Ivan (1998). Psychotherapy, Counselling and the Human Givens (Organising Idea). ISBN 1899398953.

- ↑ Griffin, Joe; Tyrrell, Ivan (2003). Human givens : a new approach to emotional health and clear thinking (First ed.). Chalvington, East Sussex: HG Publishing. ISBN 1-899398-31-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Use of the term 'organising idea' as a way of referring to human thinking/perceptual processes seems to have originated with Henri Bortoft and is much used in human givens literature. "What is an organising idea?".

- ↑ Griffin, Joe; Tyrrell, Ivan; Winn (2005). Freedom from addiction : the secret behind successful addiction busting : a practical handbook. Chalvington: HG Pub. ISBN 1-899398-46-5.

- ↑ Griffin, Joe; Tyrrell, Ivan; Winn, Denise (2004). How to lift depression ( --fast) : a practical handbook. HG Pub. ISBN 1-899398-41-4.

- 1 2 Griffin, Joe; Tyrell, Ivan (2005). Evolution and the human givens --hope for the future. HG Publishing. ISBN 1-899398-76-7.

- ↑ Yaryura-Tobias, José A.; Neziroglu, Fugen A. (1997). Biobehavioral treatment of obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders (1st ed.). New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0393702453.

- ↑ Okhai, Farouk (May 2010). "Human Givens Psychotherapy" (PDF). Arab Journal of Psychiatry. 21 (1): 9–28.

- ↑ Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

- ↑ "Teaching Proverbs from the Temples of Luxor, Egypt".

The seed includes all the possibilities of the tree. The seed will develop these possibilities, however, only if it receives corresponding energies from the sky.

- ↑ King James Bible. Matthew 4:4.

Man shall not live by bread alone...

- ↑ "Dr. Abraham Maslow, Founder Of Humanistic Psychology, Dies". New York Times. June 10, 1970. Retrieved 2010-09-26.

Dr. Abraham Maslow, professor of psychology at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., and founder of what has come to be known as humanistic psychology, died of a heart attack. He was 62 years old.

- ↑ Seligman, Martin (2002). Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment. ISBN 9780743222983.

- ↑ Seligman, Martin (2011). Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. ISBN 9781439190753.

- ↑ Griffin, Joe; Tyrrell, Ivan (2013). Human Givens: The new approach to emotional health and clear thinking. HG Publishing. ISBN 1-899398-31-7.

- ↑ Goleman, Daniel (1995). Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ (1st ed.). ISBN 9780553804911.

- ↑ See references for Chapter 5 of the new edition of the core human givens book: Griffin, Joe; Tyrrell, Ivan (2013). Human givens : The new approach to emotional health and clear thinking (New ed.). Chalvington, East Sussex: HG Publishing. pp. 97–153. ISBN 978-1899398317.

- ↑ Marmot, Michael; Ruth Bell; et al. "WORK STRESS AND HEALTH: the Whitehall II study" (PDF). Public and Commercial Services Union on behalf of Council of Civil Service Unions/Cabinet Office.

We found that during the periods of insecurity in the run up to the privatisation, civil servants in PSA suffered more physical ill-health than their unaffected counterparts and they also experienced adverse changes in some of the well-known risk factors for heart disease, such as blood pressure.

- ↑ Marmot, Michael; Ruth Bell; et al. "WORK STRESS AND HEALTH: the Whitehall II study" (PDF). Public and Commercial Services Union on behalf of Council of Civil Service Unions/Cabinet Office.

Whitehall II provides ample documentation of this: the lower the grade of employment, the less control over work. This combination of imbalance between demands and control predicted a range of illnesses. The evidence from Whitehall II suggested that low control was especially important. People in jobs characterised by low control had higher rates of sickness absence, of mental illness, of heart disease and pain in the lower back.

- ↑ Stansfeld, Stephen A.; Fuhrer, Rebecca; Head, Jenny; Ferrie, Jane; Shipley, Martin (July 1997). "Work and psychiatric disorder in the Whitehall II Study". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 43 (1): 73–81. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(97)00001-9.

- ↑ Stansfeld, S.A.; Fuhrer, R; Shipley, M.J.; Marmot, M.G. (1999). "Work characteristics predict psychiatric disorder: prospective results from the Whitehall II Study.". Occupational & Environmental Medicine. 56 (5): 302–307. doi:10.1136/oem.56.5.302.

The associations between the three Karasek work characteristics, decision authority, skill discretion, job demands, and effort-reward imbalance predicting the combined risk of psychiatric disorder at phases 2 and 3, are reported in table 1. High efforts in combination with low rewards were strikingly associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorder. This has not previously been reported.

- ↑ Wheeler, Mark. "UCLA researchers identify the molecular signature of loneliness". UCLA.

- ↑ Cole, Steve W.; Hawkley, Louise C.; et al. (2007). "Social regulation of gene expression in human leukocytes". Genome Biology. 8 (9): Article R189. doi:10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r189. PMC 2375027

. PMID 17854483.

. PMID 17854483. - ↑ "Solirary Watch - Journal Articles". Solitary Watch.

- ↑ Deci, Edward L.; Ryan, Richard M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7. ISBN 9781489922731.

- ↑ Bartholomew, K.J.; Nikos Ntoumanis; et al. (November 2011). "Self-Determination Theory and Diminished Functioning: The Role of Interpersonal Control and Psychological Need Thwarting". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 37 (11): 1459–1473. doi:10.1177/0146167211413125.

Within Self Determination Theory, the nutriments for healthy development and functioning are specified using the concept of basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. To the extent that the needs are ongoingly satisfied people will develop and function effectively and experience wellness, but to the extent that they are thwarted, people more likely evidence ill-being and non-optimal functioning. The darker sides of human behavior and experience, such as certain types of psychopathology, prejudice, and aggression are understood in terms of reactions to basic needs having been thwarted, either developmentally or proximally.

- ↑ Maslow, Abraham (July 1943). "A theory of human motivation". Psychological Review. 50 (4): 370–396. doi:10.1037/h0054346.

Thus it seems impossible as well as useless to make any list of fundamental physiological needs for they can come to almost any number one might wish, depending on the degree of specificity of description.

- ↑ Reis, Harry T.; Kennon M. Sheldon; et al. (April 2000). "Daily Well-Being: The Role of Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 26 (4): 419–435. doi:10.1177/0146167200266002.

Subsequently, we have tested the importance and generality of these needs and have found that, across many eastern and western cultures, these needs are essential for psychological health in each country we have studied (e.g., Chirkov, Ryan, Kim, & Kaplan, 2003), and we were pleased to see the new evidence on this matter provided in Sheldon et al’s target article.

- ↑ Deci, Edward L.; Richard M. Ryan; et al. (2001). "Need Satisfaction, Motivation, and Well-Being in the Work Organizations of a Former Eastern Bloc Country: A Cross-Cultural Study of Self-Determination". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 27 (8): 930–942. doi:10.1177/0146167201278002.

- ↑ Ryan, Richard M.; Edward L. Deci (Jan 2000). "Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being". American Psychologist. 55 (1): 68–78. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68.

In conclusion, the present study provides evidence in support of the self-determination model of work motivation across two very different cultures and types of work organizations. More specifically, the results suggest that the study of basic psychological needs may be relevant across quite divergent cultures with different political, economic, and value systems.

- ↑ Deikman, Arthur J. (1982). The Observing Self: Mysticism and Psychotherapy (1 ed.). Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0807029510.

- ↑ Baars, Bernard J.; Ramsøy, Thomas Z.; Laureys, Steven (December 2003). "Brain, conscious experience and the observing self". Trends in Neurosciences. 26 (12): 671–675. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2003.09.015.

- ↑ LeDoux, Joseph (2003). The emotional brain : the mysterious underpinnings of emotional life ([Nachdr.] ed.). London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0753806708.

- ↑ Libet, B; Gleason, CA; Wright, EW; Pearl, DK (1983). "Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity (readiness-potential). The unconscious initiation of a freely voluntary act.". Brain : a journal of neurology. 106 (3): 623–42. doi:10.1093/brain/106.3.623. PMID 6640273.

- ↑ Hughes, edited by Rick; Cooper,, Cary L.; Kinder, Andrew (2012). International handbook of workplace trauma support (1 ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. Chapter 9. ISBN 978-0-470-97413-1.

- ↑ Griffin, Joe; Tyrrell, Ivan; Winn, Denise (2004). How to lift depression ( --fast) : a practical handbook. Chalvington: HG Pub. ISBN 1-899398-41-4.

- ↑ Griffin, Joe; Tyrrell, Ivan; Winn, Denise (2005). Freedom from addiction : the secret behind successful addiction busting : a practical handbook. Chalvington: HG Pub. ISBN 978-1899398461.

- ↑ "What is hypnosis?".

- ↑ "Caetextia Website".

- ↑ "Ivan Tyrrell and Richard Bentall discuss patient-centred new approaches to the understanding and treatment of psychotic illness.".

- ↑ Andrews, William; Twigg, Elspeth; Minami, Takuya; Johnson, Gina (Dec 2011). "Piloting a practice research network: A 12-month evaluation of the Human Givens approach in primary care at a general medical practice". Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 84 (4): 389–405. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.2010.02004.x. PMID 22903882.

- ↑ Yates, Yvonne; Atkinson, Cathy. "Using Human Givens therapy to support the well‐being of adolescents: a case example". Pastoral Care in Education. 29 (1): 35–50. doi:10.1080/02643944.2010.548395.

- ↑ Tsaroucha, Anna; Kingston, Paul; Stewart, Tony; Walton, Ian; Corp, Nadia. "Assessing the effectiveness of the "human givens" approach in treating depression: a quasi experimental study in primary care". Mental Health Review Journal. 17 (2): 90–103. doi:10.1108/13619321211270416.

- ↑ Tsaroucha, Anna; Kingston, Paul; Corp, Nadia; Stewart, Tony; Walton, Ian. "The emotional needs audit (ENA): a report on its reliability and validity". Mental Health Review Journal. 17 (2): 81–89. doi:10.1108/13619321211270407.

- ↑ Swisher AK (2010). "Practice-based evidence.". Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 21 (2): 4. PMC 2879420

. PMID 20520757.

. PMID 20520757. - ↑ Peter Andrews, William; Peter Wislocki, Andrew; Short, Fay; Chow, Daryl; Minami, Takuya (23 September 2013). "A five-year evaluation of the Human Givens therapy using a practice research network". Mental Health Review Journal. 18 (3): 165–176. doi:10.1108/MHRJ-04-2013-0011.

- ↑ Adams, Shona. "EVALUATION OF HUMAN GIVENS 'REWIND TREATMENT' TO TREAT TRAUMA" (PDF).

- ↑ http://www.professionalstandards.org.uk/docs/.../psa-press-release---hgi-accreditation.pdf?...

External links

- The Human Givens Institute

- Professional Register of qualified HG therapists in private practice

- Human Givens Publishing

- The Human Givens Foundation

- Human Givens College

- Why We Dream

- Lift Depression

- Caetextia (context blindness)