German occupation of the Channel Islands

The Channel Islands were occupied by Nazi German forces for most of the Second World War, from 30 June 1940 until their liberation on 9 May 1945. The Bailiwick of Jersey and Bailiwick of Guernsey are two British Crown dependencies in the English Channel, near the coast of Normandy. The Channel Islands were the only part of Britain to be occupied by the German Army during the war.

Anticipating a swift victory over Britain, the occupiers experimented by using a very gentle approach that set the theme for the next five years. The island authorities adopted a similar attitude, giving rise to accusations of collaboration. However, as time progressed the situation grew gradually worse, ending in near starvation for both occupied and occupiers during the winter of 1944-45. Liberation arrived peacefully on 9 May 1945.

Before occupation

Between 3 September 1939, when the United Kingdom declared war against Germany, and 9 May 1940, little had changed in the Channel Islands. Conscription did not exist, but a number of people travelled to Britain to join up as volunteers. The horticulture and tourist trades continued as normal; the British government relaxed restrictions on travel between the UK and the Channel Islands in March 1940, enabling tourists from the UK to take morale-boosting holidays in traditional island resorts.[1] On 10 May 1940 Germany attacked the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg by air and land and the war stepped closer. The Battle of France was reaching its climax on Empire Day, 24 May, when King George VI addressed his subjects by radio, saying, "The decisive struggle is now upon us ... Let no one be mistaken; it is not mere territorial conquest that our enemies are seeking. It is the overthrow, complete and final, of this Empire and of everything for which it stands, and after that the conquest of the world. And if their will prevails they will bring to its accomplishment all the hatred and cruelty which they have already displayed."[2] The war was moving swiftly towards the islands, but still the islands did not react.

On 11 June 1940, as part of the British war effort in the Battle of France, a long range RAF aerial sortie carried out by 36 Whitley bombers against the Italian cities of Turin and Genoa departed from small airfields in Jersey and Guernsey, as part of Operation Haddock.[3] Weather conditions determined that only 10 Whitleys reached their intended targets.[4] Two bombers were lost in the action.[3]

Demilitarisation

On 15 June, after the Allied defeat in France, the British government decided that the Channel Islands were of no strategic importance and would not be defended, but did not give Germany this information. Thus despite the reluctance of Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the British government gave up the oldest possession of the Crown "without firing a single shot".[5] The Channel Islands served no purpose to the Germans other than the propaganda value of having occupied British territory. The "Channel Islands had been demilitarised and declared...' an open town' ".[6]

On 16 June 1940 the Lieutenant-Governors of each island were instructed to make available as many boats as possible to aid the evacuation of Saint-Malo. Guernsey was too far away to help at such short notice. The Bailiff of Jersey called on the Saint Helier Yacht Club in Jersey to help. Four yachts set off immediately, with 14 others being made ready within 24 hours. The first yachts arrived in Saint-Malo on the morning of 17 June and embarked troops from shore to waiting transport ships; the remaining yachts from Jersey arrived on 18 June and helped clear the last parties from land.[1]

On 17 June 1940, a plane arrived in Jersey from Bordeaux evacuating General Charles de Gaulle from France.[7] After coffee and refuelling, the plane flew on to Heston, outside London where next day the general made his historic appeal of 18 June to the French people via the BBC. The last troops left the islands on 20 June, departing so quickly that half-consumed meals and bedding were left in Castle Cornet.[8]

Evacuation

The realisation of the necessity of civilian evacuation from the Channel Islands came very late. With no forward planning and secrecy being maintained, communications between the island governments and the UK took place in an atmosphere of confusion and misinterpretation. Opinion was divided and chaos ensued with different policies adopted by the different islands. The British government concluded its best policy was to make available as many ships as possible so that islanders had the option to leave if they wanted to.

The authorities in Alderney, having no direct communication with the UK, recommended that all islanders evacuate, and all but a handful did so. The Dame of Sark, Sibyl Hathaway, encouraged everyone to stay. Guernsey evacuated 80% of children of school age, giving the parents the option of keeping their children with them, or evacuating them with their school.[9]:193 By 21 June it became apparent to the government of Guernsey that it would be impossible to evacuate everyone who wanted to leave and priority would have to be given to special categories in the time remaining. The message in Guernsey was changed to an anti-evacuation one, in total, 5,000 school children and 12,000 adults out of 42,000 were evacuated. In Jersey, where children were on holiday to help with the potato crop, 23,000 civilians registered to leave; however the majority of islanders,[10]:81 following the consistent advice of the island government, then chose to stay with only 6,600 out of 50,000 leaving on the evacuation ships. Nearby Cherbourg was already occupied by German forces before official evacuation boats started leaving on 20 June; the last official one left on 23 June,[11] though mail boats and cargo ships continued to call at the islands until 28 June.[12]:81

Most evacuated children were separated from their parents, some evacuated children were assisted financially by the "Foster Parent Plan for Children Affected by War" where each child was sponsored by a wealthy American. One girl, Paulette, was sponsored by first lady Eleanor Roosevelt.[13]

Emergency government

The British Home Office instructed the Lieutenant-Governors that in the eventuality of the recall of the representatives of the Crown, the Bailiffs should take over their responsibilities, and that the Bailiffs and Crown Officers should remain at their posts. The Lieutenant-Governor of Jersey discussed with the Bailiff of Jersey the matter of being required to carry on administration under German orders. The Bailiff considered that this would be contrary to his oath of allegiance, but he was instructed otherwise.[1]

Last-minute arrangements were made to enable British administration to legally continue under the circumstances of occupation. The withdrawal of the Lieutenant Governors on 21 June 1940 and the cutting of contact with the Privy Council prevented Royal Assent being given to laws passed by the legislatures,[14] The Bailiffs took over the civil, but not the military, functions of the Lieutenant- Governors.[11] The traditional consensus-based governments of the bailiwicks were unsuited to swift executive action, and therefore in the face of imminent occupation, smaller instruments of government were adopted. Since the legislatures met in public session, the creation of smaller executive bodies that could meet behind closed doors enabled freer discussion of matters such as how far to comply with German orders.[1]

In Guernsey, the States of Deliberation voted on 21 June 1940 to hand responsibility for running island affairs to a controlling committee, under the presidency of HM Attorney General Ambrose Sherwill MC, who was selected rather than the 69-year-old Bailiff, Victor Carey, as he was a younger and more robust person.[15]:45 The States of Jersey passed the Defence (Transfer of Powers) (Jersey) Regulation 1940 on 27 June 1940 to amalgamate the various executive committees into eight departments each under the presidency of a States Member. The presidents along with the Crown Officers made up the Superior Council under the presidency of the 48-year-old Bailiff, Capt. Alexander Coutanche.[1]

Invasion

The Germans did not realise that the islands had been demilitarised (news of the demilitarisation had been suppressed until 30 June 1940),[1] and they approached them with caution. Reconnaissance flights were inconclusive. On 28 June 1940, they sent a squadron of bombers over the islands and bombed the harbours of Guernsey and Jersey. In St Peter Port, the main town of Guernsey, some lorries lined up to load tomatoes for export to England were mistaken by the reconnaissance for troop carriers. A similar attack occurred in Jersey where nine died. In total, 44 islanders were killed in the raids. The BBC broadcast a belated message that the islands had been declared "open towns" and later in the day reported the German bombing of the island.[16]:7

While the Wehrmacht was preparing Operation Grünpfeil (Green Arrows) a planned invasion of the islands with assault troops comprising two battalions, a reconnaissance pilot, Hauptmann Liebe-Pieteritz, made a test landing at Guernsey's deserted airfield on 30 June to determine the level of defence. He reported his brief landing to Luftflotte 3 which came to the decision that the islands were not defended. A platoon of Luftwaffe airmen was flown that evening to Guernsey by Junkers transport planes. Inspector Sculpher of the Guernsey police went to the airport carrying a letter signed by the bailiff stating that "This Island has been declared an Open Island by His Majesty's Government of the United Kingdom. There are no armed forces of any description. The bearer has been instructed to hand this communication to you. He does not understand the German language." He found that the airport had been taken over by the Luftwaffe. The senior German officer, Major Albrecht Lanz, asked to be taken to the island's chief man. They went by police car to the Royal Hotel where they were joined by the bailiff, the president of the controlling committee, and other officials. Lanz announced through an interpreter that Guernsey was now under German occupation. In this way the Luftwaffe pre-empted the Wehrmacht's invasion plans.[1] Jersey surrendered on 1 July. Alderney, where only a handful of islanders remained, was occupied on 2 July and a small detachment travelled from Guernsey to Sark, which surrendered on 4 July. The first shipborne German troops consisting of two anti-aircraft units, arrived in St. Peter Port on the captured freighter SS Holland on 14 July.[17]

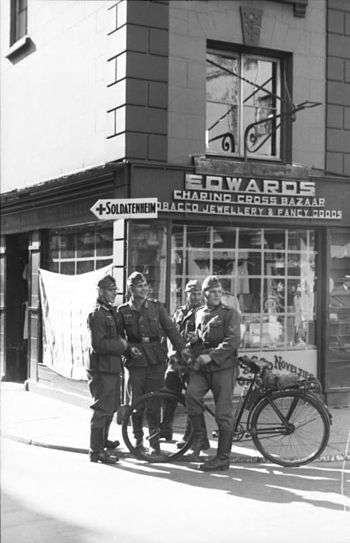

Occupation

The German forces quickly consolidated their positions. They brought in infantry, established communications and anti-aircraft defences, established an air service with occupied mainland France, and rounded up British servicemen on leave.

Administration

The Germans organised their administration as part of the department of Manche, administered as part of military government Area A based in St. Germain. Feldkommandantur 515 was set up in Jersey, with a Nebenstelle in Guernsey (also covering Sark), an Aussenstelle in Alderney, and a logistics Zufuhrstelle in Granville.[1]

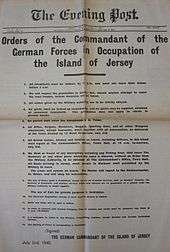

The kommandant issued an order in Guernsey on 2 July 1940 and in Jersey on 8 July 1940 instructing that laws passed by the legislatures would have to be given assent by the kommandant and that German orders were to be registered as legislation. The civil courts would continue in operation, but German military courts would try breaches of German law. At first the bailiffs submitted legislation for the assent of the kommandant signed in their capacities as lieutenant governors. At the end of 1941, the kommandant objected to this style and subsequent legislation was submitted simply signed as bailiff.[1]

The German authorities changed the Channel Island time zone from GMT to CET to bring the islands into line with most of continental Europe, and the rule of the road was also changed to driving on the right. Scrip (occupation money) was issued in the islands to keep the economy going. German military forces used the scrip for payment of goods and services. Locals employed by Germans were also paid in the Occupation Reichsmarks.

The Germans allowed entertainment to continue including cinemas and theatre; their military bands performed in public. In 1944, the popular German film actress Lil Dagover arrived to entertain German troops in Jersey and Guernsey with a theatre tour to boost morale.[18]

Allegations of collaboration

The islands' governments had a legal and moral requirement to do their best for the population of the islands. That meant preserving life until such time as the world became dominated by Germany or the islands were liberated. Mistakes were made as there were no guidelines on how a government should act when occupied. Austria was annexed, Czechoslovakia and Poland were invaded and puppet governments installed. Denmark installed a protectorate government and stayed in power taking a passive and pro German view by accepting a nonaggression pact. In Norway a government was imposed on the population, the same in the Netherlands and Belgium. France was split in two with their government keeping control of the southern zone. The Channel Islands decided their actions independent of each other and came to very similar passive views which enabled the existing civil and legal structures to remain in place.

The view of the majority of islanders about active resistance to German rule was probably expressed by John Lewis, a medical doctor on Jersey. "Any sort of sabotage was not only risky but completely counterproductive. More important still, there would be instant repercussions on the civilian population who were very vulnerable to all sorts of reprisals."[19] Sherwill seems to have expressed the views of a majority of the islanders on 18 July 1940 when he complained about a series of abortive raids by British commandos on Guernsey. "Military activities of this kind were most unwelcome and could result in loss of life among the civilian population." He asked the British government to leave the Channel Islands in peace.[20] Sherwill was later imprisoned by the Germans for his role in helping two British spies on Guernsey.[21] and when released, deported to a German internment camp.

Sherwill's situation illustrated the difficulty for the island government and their citizens cooperating—but stop short of collaborating—with their occupiers and to retain as much independence as possible from German rule. The issue of islander collaboration with the Germans remained quiescent for many years, but was ignited in the 1990s with the release of wartime archives and the subsequent publication of a book titled The Model Occupation: The Channel Islands under German Rule, 1940-1945 by Madeleine Bunting. Language such as the title of one chapter, "Resistance? What Resistance?" incited islander ire.[22] The issue of collaboration was further inflamed by the fictional television programme Island at War (2004) which featured a romance between a German soldier and an islander girl and portrayed favourably the German military commander of the occupation. Bunting's point was that the Channel Islanders did not act in a Churchillian manner, they "did not fight on the beaches, in the fields or in the streets. They did not commit suicide, and they did not kill any Germans. Instead they settled down, with few overt signs of resistance, to a hard, dull but relatively peaceful five years of occupation, in which more than half the population was working for the Germans."[23] There were suicides and since Bunting's book was published, several new books and journal articles have been published describing additional incidents of resistance, both active and passive, by islanders.

Charles Cruickshank summed up the opposing and official view about the conduct of the Channel Islands' governments under German occupation by saying "it would be difficult to voice any criticism of their relationship with the occupiers." Had the island leaders "simply kept their heads above water and done what they were told to do by the occupying power it would hardly be a matter for censure; but they carried the administrative war into the enemy camp on many occasions. It is not that they made some mistakes that is surprising, but that they did so much right in circumstances of the greatest possibly difficulty."[24]

Civilian life during the occupation

Life as a civilian during the occupation came as a shock. Having their own governments continuing to govern them softened the blow and kept most civilians at a distance from their oppressors. Many lost their jobs when businesses closed down and it was hard finding work for non German employers. As the war progressed, life became harsher and morale fell, especially when radios were confiscated and when deportations took place in September 1942. Food, fuel and medicines became scarce and crime increased. Following 6 June 1944, liberation became more likely in the popular mind, but the hardest times for the civilians was still to come as the winter of 1944-45 was very cold and hungry, the population being saved from starvation with the arrival of Red Cross parcels.

Resistance

The population actively resisting German occupation in continental European countries was between 0.6% and 3%, and the percentage of the islander population participating in active resistance is comparable.[25] From a wartime population of 66,000 in the Channel Islands [26] a total of around 4000 islanders were sentenced for breaking laws (around 2600 in Jersey and 1400 in Guernsey), although many of these were for ordinary criminal acts rather than resistance; 570 prisoners were sent to continental prisons and camps, and at least 22 people from Jersey and nine from Guernsey did not return.[11] Willmott estimated that over 200 people in Jersey provided material and moral support to escaped forced workers, including over 100 who were involved in the network of safe houses sheltering escapees.[25]

No islanders joined active German military units;[27] a small number of UK men who had been stranded in the islands at the start of the occupation joined up from prison. Eddie Chapman, an Englishman, was in prison for burglary in Jersey when the invasion occurred, and offered to work for the Germans as a spy under the code name Fritz, then became a British double agent under the code name ZigZag.

Resistance involved passive resistance, acts of minor sabotage, sheltering and aiding escaped slave workers, and publishing underground newspapers containing news from BBC radio. There was no armed resistance movement in the Channel Islands. Much of the population of military age had already joined the British or French armed forces. Because of the small size of the islands, most resistance involved individuals risking their lives to save someone else.[28] The British government did not encourage resistance in the Channel Islands.[11] Islanders joined in Churchill's V sign campaign by daubing the letter "V" (for Victory) over German signs.[15]

The Germans initially followed a policy of presenting a non-threatening presence to the resident population for its propaganda value ahead of an eventual invasion and occupation of the United Kingdom. Many islanders were willing to go along with the necessities of occupation as long as they felt the Germans were behaving in a correct and legal way. Two events particularly jolted many islanders out of this passive attitude: the confiscation of radios, and the deportation of large sections of the population.[25]

In May 1942, three youngsters, Peter Hassall, Maurice Gould, and Denis Audrain, attempted to escape from Jersey in a boat. Audrain drowned, and Hassall and Gould were imprisoned in Germany, where Gould died.[11] Following this escape attempt, restrictions on small boats and watercraft were introduced, restrictions were imposed on the ownership of photographic equipment (the boys had been carrying photographs of fortifications with them), and radios were confiscated from the population. A total of 225 islanders, such as Peter Crill, escaped from the islands to England or France: 150 from Jersey, and 75 from Guernsey.[11] The number of escapes increased after D-Day, when conditions in the islands worsened as supply routes to the continent were cut off and the desire to join in the liberation of Europe increased.

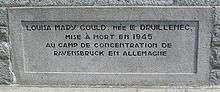

Louisa Gould hid a wireless set and sheltered an escaped Soviet prisoner. Betrayed by an informer at the end of 1943, she was arrested and sentenced on 22 June 1944. In August 1944 she was transported to Ravensbrück where she died on 13 February 1945. In 2010 she was posthumously awarded the honour British Hero of the Holocaust.

Listening to BBC radio had been banned in the first few weeks of the occupation and then (surprisingly given the policy elsewhere in Nazi-occupied Europe) tolerated for a period before being once again prohibited. In 1942 the ban became draconian, with all radio listening (even to German stations) being banned by the occupiers, a ban backed up by the confiscation of wireless sets. Denied access to BBC broadcasts, the populations of the islands felt increased resentment against the Germans and increasingly sought to undermine the rules. Hidden radio receivers and underground news distribution networks spread. Nevertheless, many islanders successfully hid their radios (or replaced them with home-made crystal sets) and continued listening to the BBC despite the risk of being discovered by the Germans or being informed on by neighbours.[29] The regular raids by German personnel hunting for radios further alienated the occupied civilian populations.[25]

A shortage of coinage in Jersey (partly caused by occupying troops taking away coins as souvenirs) led to the passing of the Currency Notes (Jersey) Law on 29 April 1941. A series of banknotes designed by Edmund Blampied was issued by the States of Jersey in denominations of 6 pence (6d), 1, 2 and 10 shillings (10/–) and 1 pound (£1). The 6d note was designed by Blampied in such a way that the word six on the reverse incorporated an outsized "X" so that when the note was folded, the result was the resistance symbol "V" for victory.[30] A year later he was asked to design six new postage stamps for the island, in denominations of ½d to 3d. As a sign of resistance, he incorporated into the design for the 3d stamp the script initials GR (for Georgius Rex) on either side of the "3" to display loyalty to King George VI.[31] Edmund Blampied forged stamps for documents for fugitives.[25]

The deportations of 1942 sparked the first mass demonstrations of patriotism of the occupation. The illegality and injustice of the measure, which contrasted with the Germans' earlier showy insistence on legality and correctness, outraged those who remained behind and encouraged many to turn a blind eye to the resistance activities of others in passive support.[25]

Soon after the sinking of HMS Charybdis on 23 October 1943, the bodies of 21 Royal Navy and Royal Marines men were washed up in Guernsey. The German authorities buried them with full military honours. The funerals became an opportunity for some of the islanders to demonstrate their loyalty to Britain and their opposition to the occupiers: around 5,000 islanders attended the funeral, laying 900 wreaths – enough of a demonstration against the occupation for subsequent military funerals to be closed to civilians by the German occupiers.[32]

Some island women fraternised with the occupying forces. This was frowned upon by the majority of islanders, who gave them the derogatory nickname Jerry-bags.[11] According to the Ministry of Defence, a very high proportion of women "from all classes and families" had sexual relations with the enemy, and 800–900 children were born to German fathers.[33] The Germans estimated their troops had been responsible for fathering 60 to 80 illegitimate births in the Channel Islands.[11] As far as official figures went, 176 illegitimate births in total had been registered in Jersey between July 1940 and May 1945; and in Guernsey 259 illegitimate births between July 1941 and June 1945 (the disparity in the official figures is explained by differing legal definitions of illegitimacy in the two jurisdictions).[11] The German military authorities tried to prohibit sexual fraternisation in an attempt to reduce incidences of sexually transmitted diseases. They opened brothels for soldiers, staffed with French prostitutes under German medical surveillance.[11]

The sight of brutality against slave workers brought home to many islanders the reality of Nazi ideology behind the punctilious façade of the occupation. Forced marches between camps and work sites by wretched workers and open public beatings rendered visible the brutality of the régime.[25]

British government reaction

His Majesty's government's reaction to the German invasion was muted, with the Ministry of Information issuing a press release shortly after the Germans landed.

On several occasions British aircraft dropped propaganda newspapers and leaflets on the islands.

Raids on the Channel Islands

- On 6 July 1940, 2nd Lieutenant Hubert Nicolle, a Guernseyman serving with the British Army, was dispatched on a fact-finding mission to Guernsey, Operation Anger.[34]:62 He was dropped off the south coast of Guernsey by a submarine and rowed ashore in a canoe under cover of night. This was the first of two visits which Nicolle made to the island.[35]:77 Following the second, he missed his rendezvous and was trapped on Guernsey. After a month and a half in hiding, he gave himself up to the German authorities and was sent to a German prisoner-of-war camp.

- On the night of 14 July 1940, Operation Ambassador was launched on Guernsey by men drawn from H Troop of No. 3 Commando under John Durnford-Slater and No. 11 Independent Company. The raiders failed to make contact with the German garrison. Four commandos were left behind and were taken prisoner.[34]:71[36]

- Operation Dryad was a successful raid on the Casquets lighthouse 2–3 September 1942.[34]:79

- Operation Branford was an uneventful raid against Burhou, an island near Alderney, on 7–8 September 1942.[34]:86

- In October 1942, there was a British Commando raid on Sark, named Operation Basalt.[34]:89 Three German soldiers were killed and one captured. Actions taken by the Commandos resulted in German retaliatory action against channel islanders and an order to execute captured Commandos.

- Operation Huckaback was a raid originally planned for the night of 9/10 February 1943, as simultaneous raids on Herm, Jethou and Brecqhou. The objective was to take prisoners and gain information about the situation in the occupied Channel Islands. Cancelled because of bad weather, Huckaback was reinvented as a raid on Herm alone. Landing on Herm and finding the island unoccupied, the Commandos left.[34]:113

- Operation Pussyfoot was also a raid on Herm, but thick fog on 3–4 April 1943 foiled the raid and the Commandos did not land.

- Operation Hardtack was a series of commando raids in the Channel Islands and the northern coast of France in December 1943. Hardtack 28 landed on Jersey on 25–26 December, after climbing the northern cliff the Commandos spoke to locals, but did not find any Germans. They suffered two casualties when a mine exploded on the return journey. Hardtack 7 was a raid on Sark on 26–27 December, failing to climb the cliffs, they returned on 27–28 December, but two were killed and most others wounded by mines when climbing, resulting in the operation failing.[34]:117

In 1943, Vice Admiral Lord Mountbatten proposed a plan to retake the islands named Operation Constellation. The proposed attack was never mounted.

Bombing and ship attacks on the islands

The RAF carried out the first bombing raids in 1940 even though there was little but propaganda value in the attacks, the risk of hitting non-military targets was great and there was a fear of German reprisals against the civilian population.[1] Twenty-two Allied air attacks on the Channel Islands during the war resulted in 93 deaths and 250 injuries, many being Organisation Todt workers in the harbours or on transports. Thirteen air crew died.[34]:137

There were fatalties caused by naval attacks amongst German soldiers and sailors, civilians and Organisation Todt workers including the Minotaur carrying 468 Organisation Todt workers including women and children from Alderney that was hit by Canadian Navy motor torpedo boats near St Malo, about 250 of the passengers killed by the explosions or by drowning, on 5 July 1944.[34]:132 [37]:119

In June 1944 Battery Blücher opened fire on American troops on the Cherbourg peninsula. HMS Rodney was called up on 12 August to fire at the battery. Using an aircraft as a spotter, it fired 72x16-inch shells at a range of 40 km. Two Germans were killed, and several injured with two of the four guns damaged.[38] Three guns were back in action in August, the fourth by November. The naval gunfire was not very effective.[34]:138

Representation in London

As self-governing Crown Dependencies, the Channel Islands had no elected representatives in the British Parliament. It therefore fell to evacuees and other islanders living in the United Kingdom prior to the occupation to ensure that the islanders were not forgotten. The Jersey Society in London,[39] which had been formed in 1896, provided a focal point for exiled Jerseymen. In 1943, several influential Guernseymen living in London formed the Guernsey Society to provide a similar focal point and network for Guernsey exiles. Besides relief work, these groups also undertook studies to plan for economic reconstruction and political reform after the end of the war. The pamphlet Nos Îles published in London by a committee of islanders was influential in the 1948 reform of the constitutions of the Bailiwicks.[40] Sir Donald Banks felt that there must be an informed voice and body of opinion among exiled Guernseymen and women that could influence the British Government, and assist the insular authorities after the hostilities were over.[41] In 1942, he was approached by the Home Office to see if anything could be done to get over a reassuring message to the islanders, as it was known that, despite the fact that German authorities had banned radios, the BBC was still being picked up secretly in Guernsey and Jersey. It was broadcast by the BBC on 24 April 1942.[42]

Bertram Falle, a Jerseyman, had been elected Member of Parliament (MP) for Portsmouth in 1910. Eight times elected to the House of Commons, in 1934 he was raised to the House of Lords with the title of Lord Portsea. During the occupation he represented the interests of islanders and pressed the British government to relieve their plight, especially after the islands were cut off after D-Day.[43]

Committees of émigré Channel islanders elsewhere in the British Empire also banded together to provide relief for evacuees. For example, Philippe William Luce (writer and journalist, 1882–1966) founded the Vancouver Channel Islands Society in 1940 to raise money for evacuees.[44]

German reaction

Restrictions

On arrival in the islands, the Germans issued proclamations imposing new laws on the resident islanders. As time progressed, additional laws restricting rights were posted and had to be obeyed. The restrictions included:

|

Confiscation of: |

Restrictions on:

|

Changes to: |

Forced to accept:

|

Fortification and construction

As part of the Atlantic Wall, between 1940 and 1945 the occupying German forces and the Organisation Todt constructed fortifications, roads and other facilities in the Channel Islands. In a letter from the Oberbefehlshaber West dated 16 June 1941, the reinforcing of the islands was to be carried out on orders of Hitler, since an Allied attack "must be reckoned with" in Summer 1941.[58] Much of work was carried out by imported labour, including thousands from the Soviet Union,[59] and under the supervision of the German forces.[60] The Germans transported over 16,000 slave workers to the Channel Islands to build fortifications. Five categories of construction worker were employed (or used) by the Germans.

Paid foreign labour was recruited from occupied Europe, including French, Belgian and Dutch workers—including some members of resistance movements who used the opportunity to travel to gain access to maps and plans.[27]

Conscripted labourers from France, Belgium and the Netherlands were also assigned. In 1941 hundreds of unemployed French Algerians and Moroccans were handed to the Germans by the Vichy government and sent to Jersey. Around 2000 Spaniards who had taken refuge in France after the Spanish Civil War and who had been interned were handed over for forced labour.[27]

Most of the Soviet slave workers came from Ukraine.[27] 1,000 French Jews were imported.[61]

The problem of the use of local labour arose early in the occupation. In a request for labour dated 19 July 1941, the Oberbefehlshaber West cited the "extreme difficulty" of procuring local civilian labour.[58] On 7 August Deputy Le Quesne, who was in charge of Jersey's Labour Department, refused a German order to provide labour for improvements at Jersey Airport on the grounds that this would be to provide military assistance to the enemy. On 12 August the Germans stated that unless labour was forthcoming men would be conscripted. The builders who had originally built the airport undertook the work under protest. In the face of threats of conscription and deportation to France, resistance to the demands led to an ongoing tussle over the interpretation of the Hague Convention and the definition of military and non-military works. An example that arose was to what extent non-military "gardening" was being intended as military camouflage. On 1 August 1941 the Germans accepted that the Hague Convention laid down that no civilian could be compelled to work on military projects. The case of the reinforcement of sea walls, which could legitimately be described as civilian sea defences (important for islands) but were undeniably of military benefit in terms of coastal defence, showed how difficult it was to distinguish in practice. Economic necessity drove many islanders to take up employment offered by the Germans, taking the opportunity to sabotage or delay works, and to steal tools and provisions. Lorry drivers siphoned off scarce petrol to barter for food with farmers. The Germans also induced civilian labour by offering those who contravened curfew or other regulations employment on building projects as an alternative to deportation to Germany.[27]

The fifth category of labour were British conscientious objectors and Irish citizens. As many of the islands' young men had joined the armed forces at the outbreak of war, there was a shortfall in manual labour on the farms, particularly for the potato crop. 150 registered conscientious objectors associated with the Peace Pledge Union and 456 Irish workers were recruited for Jersey. Some chose to remain and were trapped by the occupation. Some of the conscientious objectors were communists and regarded the German-Soviet pact as a justification for working for the Germans. Others participated in non-violent resistance activities. As the Irish workers were citizens of a neutral country (see Irish neutrality during World War II), they were free to work for the Germans as they wished and many did so. The Germans attempted to foster anti-British and IRA sympathies with propaganda events aimed at the Irish (see also Irish Republican Army – Abwehr collaboration in World War II). John Francis Reilly convinced 72 of his fellow Irishmen in 1942 to volunteer for employment at the Hermann Göring ironworks near Brunswick. Conditions were unpleasant and they returned to Jersey in 1943. Reilly stayed behind in Germany to broadcast on radio and joined the SS Sicherheitsdienst.[27]

The Channel Islands were amongst the most heavily fortified parts of the Atlantic Wall, particularly Alderney which is the closest to France. On 20 October 1941 Hitler signed a directive, against the advice of Commander-in-Chief von Witzleben, to turn the Channel Islands into an "impregnable fortress". In the course of 1942, one twelfth of the resources funnelled into the whole Atlantic Wall was dedicated to the fortification of the Channel Islands.[25] Hitler had decreed that 10% of the steel and concrete used in the Atlantic Wall go to the Channel Islands. It is often said the Channel Islands were better defended than the Normandy beaches, given the large number of tunnels and bunkers around the islands. By 1944 in tunneling alone, 244,000 m3 of rock had been extracted collectively from Guernsey, Jersey and Alderney (the majority from Jersey). At the same point in 1944 the entire Atlantic Wall from Norway to the Franco-Spanish border, excluding the Channel Islands, had extracted some 225,000 m3.[62]

Light railways were built in Jersey and Guernsey to supply coastal fortifications. In Jersey, a one-metre gauge line was laid down following the route of the former Jersey Railway from St Helier to La Corbière, with a branch line connecting the stone quarry at Ronez in St John. A 60 cm line ran along the west coast, and another was laid out heading east from St Helier to Gorey. The first line was opened in July 1942, the ceremony being disrupted by passively-resisting Jersey spectators.[1] The Alderney Railway was taken over by the Germans who lifted part of the standard gauge line and replaced it with a metre gauge line, worked by two Feldbahn 0-4-0 diesel locomotives. The German railway infrastructure was dismantled after the liberation in 1945.

Alderney camps

The Germans built many camps in Jersey, Guernsey and four camps in Alderney. The Nazi Organisation Todt operated each camp and used forced labour to build bunkers, gun emplacements, air raid shelters, and concrete fortifications.

In Alderney the camps commenced operation in January 1942 and had a total inmate population of about 6,000. The Borkum and Helgoland camps were "volunteer" (Hilfswillige) labour camps[63] Lager Borkum was used for German technicians and "volunteers" from different countries of Europe. Lager Helgoland was filled with Soviet Organisation Todt workers and the labourers in those camps were paid for work done which was not the case with inmates at the two concentration camps, Sylt and Norderney. The prisoners in Lager Sylt and Lager Norderney were slave labourers. Sylt camp held Jewish forced labourers.[64] Norderney camp housed European (mainly Eastern Europeans but including Spaniards) and Soviet forced labourers. On 1 March 1943, Lager Norderney and Lager Sylt, were placed under the control of the SS Hauptsturmführer Max List, turning them into concentration camps. Over 700 of the inmates of the four camps lost their lives in Alderney or in ships travelling to/from Alderney before the camps were closed and the remaining inmates transferred to France, mainly in mid-1944. [64][65]

Repressions

Repressions affected many people in the islands, the worse affected were the Jews. A small number of foreign and British Jews lived on the Channel Islands during the occupation. Most of the Channel Island's Jews evacuated in June 1940, but British laws did not allow enemy citizens, irrespective of their religion, to enter Britain without a permit. There were 18 Jews in the islands when the Germans arrived who registered out of an estimated 30 to 50.[11] Soon after the occupation occurred, officials issued the first anti-Jewish Order (October 1940) which instructed the police to identify Jews as part of the civilian registration process. Island authorities complied, and registration cards were marked with red “J”s; additionally, a list was compiled of Jewish property, including property owned by island Jews who had evacuated, which was turned over to German authorities. The registered Jews in the islands, often Church of England members with one or two Jewish grandparents, were subjected to the nine Orders Pertaining to Measures Against the Jews, including closing their businesses (or placing them under Aryan administration), giving up their wirelesses, and staying indoors for all but one hour per day. The civil administrations agonised over how far they could oppose the registration of these orders.[11] The process developed differently on the three islands. Local officials made some effort to mitigate anti-Semitic measures by the Nazi occupying force, and as such refused to require Jews to wear identifying yellow stars and had most former Jewish businesses returned after the war, officials in the registration department also procured false documents for some of those who fell within categories suspected by the Germans.[11] The anti-Jewish repressions were not carried out systematically. Some well-known Jews lived through the occupation in comparative openness, including Marianne Blampied, the wife of artist Edmund Blampied.[11] Three Jewish women of Austrian and Polish nationality, Therese Steiner, Auguste Spitz, and Marianne Grünfeld, had fled Central Europe to Guernsey in the 1930s but had been unable to leave Guernsey as part of the evacuation in 1940 because they were excluded by UK law. 18 months later, Steiner alerted the Germans to her presence and the three were deported to France in April 1942 to be later shipped to Auschwitz where they died.[11]

Freemasonry was suppressed by the Germans. The Masonic Temples in Jersey and Guernsey were ransacked in January 1941 and furnishings and regalia were seized and taken to Berlin for display. Lists of membership of Masonic lodges were examined. The States in both bailiwicks passed legislation to nationalise Masonic property later in 1941 in order to protect the buildings and assets. The legislatures resisted attempts to pass anti-Masonic measures and no individual Freemason was persecuted for his adherence. Scouting was banned, but continued undercover,[66] as did the Salvation Army.

Deportations

On specific orders from Adolf Hitler, in 1942, the German authorities announced that all residents of the Channel Islands who were not born in the islands, as well as those men who had served as officers in World War I, were to be deported. The majority of them were transported to the south west of Germany, to Ilag V-B at Biberach an der Riss and Ilag VII at Laufen, and Wurzach. This deportation order was originally issued in 1941, as a reprisal for the 800 German civilians in Iran[67] being deported and interned. The ratio was 20 Channel Islanders to be interned for every German interned but its enactment was delayed and then diluted. The fear of internment caused suicides in all three islands. Guernsey nurse Gladys Skillett, who was five months pregnant at the time of her deportation to Biberach, became the first Channel Islander to give birth while in captivity in Germany.[68] 45 of the 2,300 deported would die before the war ended.

Imprisonment

|

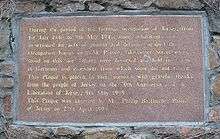

In Jersey, 22 islanders are recognised as having died as a consequence of having been sent to Nazi prisons and concentration camps. They are commemorated on Holocaust Memorial Day:[69]

|

In Guernsey, the following are recognised as having died having been jailed.

Memorial, St. Helier: "In memoriam: between 1940 and 1945, more than 300 islanders were taken from Jersey to concentration camps and prisons on the continent, for political crimes committed against the German occupying forces." |

Under siege

During June 1944, the Allied Forces launched the D-Day landings and the liberation of Normandy. They decided to bypass the Channel Islands due to their heavy fortifications described above. As a result, German supply lines for food and other supplies through France were completely severed. The islanders' food supplies were already dwindling, and this made matters considerably worse – the islanders and German forces alike were on the point of starvation.

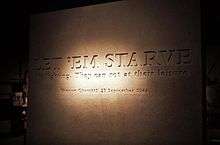

In August 1944, the German Foreign Ministry made an offer to Britain, through the Swiss Red Cross, that would see the release and evacuation of all Channel Island civilians except for men of military age. This was not a possibility that the British had envisaged. The British considered the offer, a memorandum from Winston Churchill stating "Let 'em starve. They can rot at their leisure", it is not clear whether Churchill meant the Germans, or the civilians. The German offer was rejected in late September.[34]:155

In September 1944 a ship sailed from France to Guernsey under a white flag. The American on board asked the Germans if they were aware of their hopeless position. The Germans refused to discuss surrender terms and the American sailed away.[71]:54

It took months of protracted negotiations before the International Committee of the Red Cross ship SS Vega was permitted to bring relief to the starving islanders in December 1944, carrying Red Cross parcels, salt and soap, as well as medical and surgical supplies. Vega made five further trips to the islands, the last after the islands were liberated on 9 May 1945.

The Granville Raid occurred on the night of 8–9 March 1945, when a German raiding force from the Channel Islands landed in Allied-occupied France and brought back supplies to their base.[72] Granville had been the headquarters of Dwight D. Eisenhower for three weeks, six months earlier.[73]

Liberation

Liberation

Although plans had been drawn up and proposed in 1943 by Vice Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten for Operation Constellation, a military reconquest of the islands, these plans were never carried out. The Channel Islands were liberated after the German surrender.

On 8 May 1945 at 10:00 the islanders were informed by the German authorities that the war was over. Churchill made a radio broadcast at 15:00 during which he announced that:

- Hostilities will end officially at one minute after midnight tonight, but in the interests of saving lives the "Cease fire" began yesterday to be sounded all along the front, and our dear Channel Islands are also to be freed today.[74]

The following morning, 9 May 1945, HMS Bulldog arrived in St Peter Port, Guernsey and the German forces surrendered unconditionally aboard the vessel at dawn. British forces landed in St Peter Port shortly afterwards, greeted by crowds of joyous but malnourished islanders singing, amongst other patriotic songs, "Sarnia-Cherie".[75]

HMS Beagle, which had set out at the same time from Plymouth, performed a similar role in liberating Jersey. Two naval officers, Surgeon Lieutenant Ronald McDonald and Sub Lieutenant R. Milne, were met by the harbourmaster who escorted them to his office where they hoisted the Union Flag, before also raising it on the flagstaff of the Pomme D'Or Hotel. It appears that the first place liberated in Jersey may have been the British General Post Office Jersey repeater station. Mr Warder, a GPO lineman, had been stranded in the island during the occupation. He did not wait for the island to be liberated and went to the repeater station where he informed the German officer in charge that he was taking over the building on behalf of the British Post Office.[76]

Sark was liberated on 10 May 1945, and the German troops in Alderney surrendered on 16 May 1945. The German prisoners of war were removed from Alderney by 20 May 1945, and its population started to return in December 1945, after clearing up had been carried out by German troops under British military supervision.

Aftermath

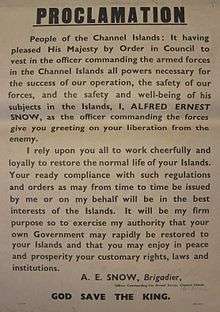

The main Liberation forces arrived in the islands on 12 May 1945. A Royal Proclamation read out by Brigadier Alfred Snow in both Guernsey and Jersey vested the authority of military government in him. The British Government had planned for the relief and restoration of order in the islands. Food, clothing, pots, pans and household necessities had been stockpiled so as to supply islanders immediately. It was decided that to minimise financial disruption Reichsmarks would continue in circulation until they could be exchanged for sterling.[1]

In Sark, the Dame was left in command of the 275 German troops in the island until 17 May when they were transferred as prisoners of war to England. The UK Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison, visited Guernsey on 14 May and Jersey on 15 May and offered an explanation in person to the States in both bailiwicks as to why it had been felt in the interests of the islands not to defend them in 1940 and not to use force to liberate them after D-Day.[1]

On 7 June the King and Queen visited Jersey and Guernsey to welcome the oldest possessions of the Crown back to freedom.[1]

Since the state of affairs in the islands had been largely unknown and there had been uncertainty as to the extent of resistance by the German forces, the Defence (Channel Islands) Regulations of 1944 had vested sweeping administrative powers in the military governor. As it turned out that the German surrender was entirely peaceful and orderly and civil order had been maintained, these regulations were used only for technical purposes such as reverting to Greenwich Mean Time. Each bailiwick was left to make its own regulations as necessary. The situation of retrospectively regularising legislation passed without Royal Assent had to be dealt with. Brigadier Snow signed regulations on 13 June (promulgated 16 June) to renew orders in Jersey and ordinances in Guernsey as though there had been no interruption in their technical validity. The period of military government lasted until 25 August 1945 when new Lieutenant Governors in each bailiwick were appointed.[1]

Following the liberation of 1945, allegations of collaboration with the occupying authorities were investigated. By November 1946, the UK Home Secretary was in a position to inform the House of Commons[77] that most of the allegations lacked substance and only 12 cases of collaboration were considered for prosecution, but the Director of Public Prosecutions had ruled out prosecutions on insufficient grounds. In particular, it was decided that there were no legal grounds for proceeding against those alleged to have informed to the occupying authorities against their fellow citizens.[78] The only trials connected to the occupation of the Channel Islands to be conducted under the Treachery Act 1940 were against individuals from among those who had come to the islands from Britain in 1939–1940 for agricultural work. These included conscientious objectors associated with the Peace Pledge Union and people of Irish extraction.[11] In December 1945 a list of British honours was announced to recognise a certain number of prominent islanders for services during the occupation.[79]

In Jersey and Guernsey, laws[80][81] were passed to confiscate retrospectively the financial gains made by war profiteers and black marketeers, although these measures also affected those who had made legitimate profits during the years of military occupation.

'Jerry-bags' were women who had fraternised with German soldiers. This had aroused indignation among some citizens. In the hours following the liberation, members of the British liberating forces were obliged to intervene to prevent revenge attacks.[82]

For two years after the liberation, Alderney was operated as a communal farm. Craftsmen were paid by their employers, whilst others were paid by the local government out of the profit from the sales of farm produce. Remaining profits were put aside to repay the British government for repairing and rebuilding the island. As a result of resentment by the local population about not being allowed to control their own land, the Home Office set up an enquiry that led to the "Government of Alderney Law 1948", which came into force on 1 January 1949. The law provided for an elected States of Alderney, a justice system and, for the first time in Alderney, the imposition of taxes. Due to the small population of Alderney, it was believed that the island could not be self-sufficient in running the airport and the harbour, as well as in providing an acceptable level of services. The taxes were therefore collected into the general Bailiwick of Guernsey revenue funds (at the same rate as Guernsey) and administered by the States of Guernsey. Guernsey became responsible for many governmental functions and services.

Particularly in Guernsey, which evacuated the majority of school-age children ahead of the occupation, the occupation weakened the indigenous culture of the island. Many felt that the children "left as Guerns and returned as English". This was particularly felt in the loss of the local dialect – children who were fluent in Guernesiais when they left, found that after five years of non-use they had lost much of the language.

The abandoned German equipment and fortifications posed a serious safety risk and there were many accidents after the occupation resulting in several deaths. Many of the bunkers, batteries and tunnels can still be seen today. Some have been restored, such as Battery Lothringen and Ho8, and are open for the general public to visit. After the occupation, the islanders used some of the fortifications for other purposes, but most were stripped out in scrap drives (and by souvenir hunters) and left abandoned. One bunker was transformed into a fish hatchery and a large tunnel complex was made into a mushroom farm.

The islands were seriously in debt, with the island governments owing over £10,000,000,[83]:200 having had to pay for the evacuation ships, the costs incurred by evacuees in the UK, the cost of the "occupation forces", being wages, food, accommodation and transport as well as the cost of providing domestics for the Germans, providing civilian work for islanders and needing to pay for reconstruction and compensation after the war. Taxation receipts having fallen dramatically during the war period. Finally, the now worthless Occupation Reichsmarks and RM bank deposits were converted back to Sterling at the rate of 9.36RM to £1.[84]:307 Part of this debt was met by a "gift" from the UK government of £3,300,000 which was used to reimburse islanders who had suffered damage and loss. In addition, the cost of maintaining the evacuees, estimated at £1,000,000 was written off by the government.[85]:214 As one could buy a house for £250 in the 1940s, the gift was equivalent to the value of 17,000 houses.

War crime trials

After World War II, a court-martial case was prepared against ex-SS Hauptsturmführer Max List (the former commandant of Lagers Norderney and Sylt), citing atrocities in Alderney.[86] He did not stand trial, and is believed to have lived near Hamburg until his death in the 1980s.[87]

Legacy

- Since the end of the occupation, the anniversary of Liberation Day has been celebrated in Jersey and Guernsey on 9 May as a national holiday (see Liberation Day (Jersey)); Sark marks Liberation Day on 10 May.[88] In Alderney there was no official local population to be liberated, so Alderney celebrates "Homecoming Day" on 15 December to commemorate the return of the evacuated population. The first shipload of evacuated citizens from Alderney returned on this day.[89]

- Many islanders and evacuees have published their memoirs and diaries of this period.

- The Channel Islands Occupation Society[90][91] was formed in order to study and preserve the history of this period.

- Castle Cornet was presented to the people of Guernsey in 1947 by the Crown as a token of their loyalty during two world wars.[92]

- Some German fortifications have been preserved as museums, including the Underground Hospitals built in Jersey (Hohlgangsanlage 8) and Guernsey.[93]

- Liberation Square in Saint Helier, Jersey, is now a focal point of the town, and has a sculpture which celebrates the liberation of the island. The Liberation monument in Saint Peter Port, Guernsey, is in the form of a monumental sundial unveiled on 9 May 1995: the obelisk that acts as gnomon has 50 layers, with the top 5 sheared to represent the loss of freedom for five years during the occupation – the sundial is so constructed that on 9 May each year the shadow points to inscriptions telling the story of Liberation hour by hour.[94]

- In Jersey the end of the occupation was also marked with a penny inscribed "Liberated 1945". One million were produced between 1949 and 1952.[95]

- In 1950 the States of Jersey purchased the headland at Noirmont, site of intense fortification (see Battery Lothringen), as a memorial to all Jerseymen who perished. A memorial stone was unveiled at Noirmont on 9 May 1970 to mark the 25th anniversary of Liberation.[96]

- Saint Helier is twinned (since 2002) with Bad Wurzach, where deported Channel Islanders were interned.[97]

- In 1966, Norman Le Brocq and 19 other islanders were awarded gold watches by the Soviet Union as a sign of gratitude for their role in the resistance movement.

- Former fugitives who had been sheltered by islanders were included among the guests at 50th anniversary celebrations of the Liberation in 1995.[25]

- On 9 March 2010 the award of British Hero of the Holocaust was made to 25 individuals posthumously, including 4 Jerseymen, by the United Kingdom government in recognition of British citizens who assisted in rescuing victims of the Holocaust. The Jersey recipients were Albert Bedane, Louisa Gould, Ivy Forster and Harold Le Druillenec. It was, according to historian Freddie Cohen, the first time that the British Government recognised the heroism of islanders during the German occupation.[28]

Music

- The Liberation Jersey International Music Festival[98] was set up in Jersey in 2008 to remember the period of occupation.

- John Ireland's Fantasy-Sonata for Clarinet and Piano (1943) was partly inspired by his experience in being evacuated from the Channel Islands in advance of the occupation.

- In her song "Alderney", which appears on her album The Sea Cabinet, singer-songwriter Gwyneth Herbert tells the story of the sudden evacuation of the inhabitants of Alderney when the war broke out. She sings about the irrevocable changes introduced during the Nazi occupation of the island and their effect on the islanders.[99][100]

TV and films

- Several documentaries have been made about the occupation, mixing interviews with participants, both islanders and soldiers, archive footage, photos and manuscripts and modern day filming around the extensive fortifications still in place. These films include:

- High Tide Productions' In Toni's Footsteps: The Channel Island Occupation Remembered[101] – 52min documentary tracing the history of the occupation following the discovery of a notebook in an attic in Guernsey belonging to a German soldier named Toni Kumpel.

- There have also been TV and film dramas set in the occupied islands:

- Appointment with Venus, a film set on the fictional island of Armorel (based on the island of Sark).

- ITV's Enemy at the Door, set in Guernsey and shown between 1978 and 1980

- Triple Cross (1966) has a passage set in Jersey in the period shortly after the German occupation commences.

- The Eagle Has Landed (1977), directed by John Sturges, had a passage set in Alderney where Radl (Robert Duvall) meets Steiner (Michael Caine).

- A&E's Night of the Fox (1990), set in Jersey shortly before D-Day in 1944.

- ITV's Island at War (2004), a drama set in the fictional Channel Island of St Gregory. It was shown by US TV network PBS as part of its Masterpiece Theatre series in 2005.

- The 2001 film The Others starring Nicole Kidman was set in Jersey in 1945 just after the end of the occupation.

- The Blockhouse, a film starring Peter Sellers and Charles Aznavour, set in occupied France, was filmed in a German bunker and on L'Ancresse common in Guernsey in 1973.[102]

Plays

- A stage play, Dame of Sark, by William Douglas-Home, is set in Sark during the German occupation, and is based on the Dame's diaries of this period. It was televised by Anglia Television in 1976, and starred Celia Johnson. It was directed by Alvin Rakoff and adapted for the small screen by David Butler.

- Another stage play, "Lotty's War" by Giuliano Crispini, is set in the islands during the occupation, with the story based on "unpublished diaries".[103]

Novels

The following novels have been set in the German-occupied islands:

- Higgins, Jack (1970), A Game for Heroes, New York: Berkley, ISBN 0-440-13262-2

- Tickell, Jerrard (1976), Appointment with Venus, London: Kaye and Ward, ISBN 0-7182-1127-8

- Robinson, Derek (1977), Kramer's War, London: Hamilton, ISBN 0-241-89578-2

- Trease, Geoffrey (1987), Tomorrow Is a Stranger (London: Mammoth, ISBN 0-434-96764-5) set during the occupation of Guernsey.

- Edwards, G. B. (1981), The Book of Ebenezer Le Page (London: Hamish Hamilton, ISBN 0-241-10477-7) includes the occupation of Guernsey.

- Parkin, Lance (1996), Just War, New Doctor Who adventures series, Doctor Who Books, ISBN 0-426-20463-8

- Binding, Tim (1999), Island Madness, London: Picador, ISBN 0-330-35046-3

- Link, Charlotte (2000), Die Rosenzüchterin [The Rose Breeder], condensed ed., Köln: BMG-Wort, ISBN 3-89830-125-7

- Walters, Guy (2005), The Occupation, London: Headline, ISBN 0-7553-2066-2

- Shaffer, Mary Ann and Barrows, Annie (2008), The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, New York: The Dial Press, ISBN 978-0-385-34099-1

- Cone, Libby (2009), War on the Margins, London: Duckworth, ISBN 978-0-7156-3876-7

- Andrews, Dina (2011), Tears in the Sand, Trafford, ISBN 978-1-4269-7006-1

- Horlock, Mary (2011), The Book of Lies, Canongate, ISBN 978-1-84767-885-0

- Lea, Caroline (2016), When The Sky Fell Apart, Text Publishing Company, ISBN 978-1-9252-4074-0

See also

- Fort Hommet 10.5 cm Coastal Defence Gun Casement Bunker

- German Fortifications in Jersey

- Henri Gonay, Belgian airman killed in Jersey, 1944

- Military history of France during World War II

- Neuengamme concentration camp subcamp list

- Walker Collection A collection of philatelic material in the British Library relating to the occupation.

- William John Corbet, escaper

- Aviation accidents and incidents in the Channel Islands in the 1940s

- Sark during the German occupation of the Channel Islands

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Cruickshank, Charles G. (1975) The German Occupation of the Channel Islands, The Guernsey Press, ISBN 0-902550-02-0

- ↑ Denis, Judd (2012). George VI. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. p. 191. ISBN 9781780760711.

- 1 2 "11 June 1940". Homepage.ntlworld.com. 11 June 1940. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ↑ Cook, Tim (2004). Volume 1 of History of World War II. Marshall Cavendish Corporation. p. 281. ISBN 076147482X.

- ↑ Hazel R. Knowles Smith, The changing face of the Channel Islands Occupation (2007, Palgrave Macmillan, UK)

- ↑ Falla, Frank (1967). The Silent War. Burbridge. ISBN 0-450-02044-4.

- ↑ De Gaulle, Charles. The complete war memoirs of Charles de Gaulle. ISBN 0-7867-0546-9.

- ↑ Marr, James. Bailiwick Bastions. ISBN 0 902550 11 X.

- ↑ Lowe, Roy. Education and the Second World War: Studies in Schooling and Social Change. Routledge, 2012. ISBN 978-1-136-59015-3.

- ↑ Hamon, Simon. Channel Islands Invaded: The German Attack on the British Isles in 1940 Told Through Eye-Witness Accounts, Newspapers Reports, Parliamentary Debates, Memoirs and Diaries. Frontline Books, 2015. ISBN 978-1-4738-5160-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Sanders, Paul (2005). The British Channel Islands under German Occupation 1940–1945. Jersey: Jersey Heritage Trust / Société Jersiaise. ISBN 0953885836.

- 1 2 Sherwill, Ambrose. A fair and Honest Book. ISBN 978-1-84753-149-0.

- ↑ "Eleanor Roosevelt and the Guernsey Evacuee | Guernsey Evacuees Oral History". Guernseyevacuees.wordpress.com. 6 December 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ↑ Duret Aubin, C. W. (1949). "Enemy Legislation and Judgments in Jersey". Journal of Comparative Legislation and International Law. 3. 31 (3/4): 8–11.

- 1 2 Turner, Barry. Outpost of Occupation: The Nazi Occupation of the Channel Islands, 1940-1945. Aurum Press (April 1, 2011). ISBN 978-1845136222.

- ↑ Drawmer, Gwen. My Memories of the German Occupation of Sark, 1940-1945. Studio House, 2001.

- ↑ Hamon, Simon (2015). Channel Islands Invaded: The German Attack on the British Isles in 1940 Told Through Eye-Witness Accounts, Newspapers Reports, Parliamentary Debates, Memoirs and Diaries. Frontline Books. p. 214. ISBN 1473851599.

- ↑ Lil Dagover: Schauspielerin

- ↑ Lewis, Dr. John (1982), A Doctor's Occupation,, St. John, Jersey: Channel Island Publishing, p. 44

- ↑ Cruickshank, p. 89

- ↑ Cruickshank, p. 222

- ↑ Bunting, Madeleine (1995), The Model Occupation: The Channel Islands under German Rule, 1940-1945, London: Harper Collins Publisher, p. 191

- ↑ Bunting, p. 316

- ↑ Cruickshank, p. 329

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Willmot, Louise (May 2002). "The Goodness of Strangers: Help to Escaped Russian Slave Labourers in Occupied Jersey, 1942–1945". Contemporary European History. 11 (2): 211–227. doi:10.1017/s0960777302002023. JSTOR 20081829.

- ↑ Willmot, Louise, (May 2002) The Goodness of Strangers: Help to Escaped Russian Slave Labourers in Occupied Jersey, 1942-1945," Contemporary European History, Vol. 11, No. 2, p. 214. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ginns, Michael (2009). Jersey Occupied: The German Armed Forces in Jersey 1940–1945. Channel Island Publishing. ISBN 1905095295.

- 1 2 Senator is a driving force behind move for international recognition, Jersey Evening Post, 9 March 2010

- ↑ Bunting (1995); Maughan (1980)

- ↑ Edmund Blampied, Marguerite Syvret, London 1986 ISBN 0-906030-20-X

- ↑ Cruickshank (1975)

- ↑ Charybdis Association (1 December 2010). "H.M.S. Charybdis: A Record of Her Loss and Commemoration". World War 2 at Sea. naval-history.net. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ↑ James, Barry (4 December 1996). "Documents Show Government's Concern : Was Duke of Windsor A Nazi Sympathizer?". The New York Times.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Fowler, Will. The Last Raid: The Commandos, Channel Islands and Final Nazi Raid. The History Press. ISBN 978-0750966375.

- ↑ Tabb, Peter. A peculiar occupation. Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0711031135.

- ↑ Durnford-Slater 1953, pp. 22–33.

- ↑ Forty, George. ATLANTIC WALL: CHANNEL ISLANDS:. Pen and Sword (June 2002). ISBN 978-0850528589.

- ↑ Partridge, Colin. The Fortifications of Alderney. Alderney Publishers. ISBN 0-9517156-0-7.

- ↑ Jerseysocietyinlondon.org

- ↑ Balleine's History of Jersey, Marguerite Syvret and Joan Stevens (1998) ISBN 1-86077-065-7

- ↑ Kinnerley, RA, Obituary: Major-General Sir Donald Banks, KCB DSO MC TD, Review of the Guernsey Society, Winter 1975

- ↑ Banks, Sir Donald, Sand and Granite, Quarterly Review of the Guernsey Society, Spring 1967

- ↑ "HL Deb 04 October 1944 vol 133 cc365-6". Hansard.

- ↑ "Guernsey evacuees and kind canadians during the second world war". Exodus.

- 1 2 3 "The First Attack on England". Calvin.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nettles, John. Jewels and Jackboots. Channel Island Publishing; 1st Limited edition edition (25 October 2012). ISBN 978-1-905095-38-4.

- ↑ "Guernsey files reveal how islanders defied Nazi occupation". The Guardian.

- 1 2 Winterflood, Herbert. Occupied Guernsey : July 1940-December 1942. Guernsey Press. ISBN 978-0-9539166-6-5.

- ↑ Tremayne, Julia. War on Sark: The secret letters of Julia Tremayne. Webb & Bower (1981). ISBN 978-0906671412.

- 1 2 Hamon, Simon. Channel Islands Invaded: The German Attack on the British Isles in 1940 Told Through Eye-Witness Accounts, Newspapers Reports, Parliamentary Debates, Memoirs and Diaries. Frontline Books, 2015. ISBN 978-1-4738-5162-7.

- 1 2 Evans, Alice. Guernsey Under Occupation: The Second World War Diaries of Violet Carey. The History Press (2009). ISBN 978-1-86077-581-9.

- ↑ Tabb, Peter. A peculiar occupation. Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7110-3113-5.

- ↑ Parker, William. Life in Occupied Guernsey: The Diaries of Ruth Ozanne 1940-45. Amberley Publishing Limited, 2013. ISBN 978-1-4456-1260-7.

- ↑ Le Page, Martin. A Boy Messenger's War: Memories of Guernsey and Herm 1938-45. Arden Publications (1995). ISBN 978-0-9525438-0-0.

- ↑ Carre, Gilly. Protest, Defiance and Resistance in the Channel Islands. Bloomsbury Academic (August 14, 2014). ISBN 978-1-4725-0920-8.

- ↑ Cruickshank, Charles. The German Occupation of the Channel Islands. The History Press; New edition edition (30 Jun. 2004). ISBN 978-0-7509-3749-8.

- ↑ Le Tissier, Richard. Island Destiny: A True Story of Love and War in the Channel Island of Sark. Seaflower Books. ISBN 978-1903341360.

- 1 2 Russian State Military Archives, Inventory 500, Documents of the OB West.

- ↑ "Occupation Memorial HTML Library". Thisisjersey.co.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "Occupation Memorial | Resources | Forced Workers". Thisisjersey.co.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ The British Channel Islands; 1940-45 (Historical Boys Clothing)

- ↑ Jersey's German Tunnels by Michael Ginns MBE, CIOS Jersey

- ↑ Christian Streit: Keine Kameraden: Die Wehrmacht und die Sowjetischen Kriegsgefangenen, 1941–1945, Bonn: Dietz (3. Aufl., 1. Aufl. 1978), ISBN 3-8012-5016-4 –

- 1 2 Subterranea Britannica (February 2003). "SiteName: Lager Sylt Concentration Camp". Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ↑ Alderney, a Nazi concentration camp on an island Anglo-NormanMatisson Consultants. "Aurigny ; un camp de concentration nazi sur une île anglo-normande (English: Alderney, a Nazi concentration camp on an island Anglo-Norman)" (in French). Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ↑ Scouting in Occupied Countries: Part Eight

- ↑ Bunting (1995)

- ↑ "Gladys Skillett : wartime deportee and nurse". The Times. London. 27 February 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ↑ "The 22 Islanders who died in Nazi captivity". Jersey Evening Post. 28 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Guernsey resistance to German occupation 'not recognised'". BBC. 3 October 2014.

- ↑ Marshall, Michael (1967). Hitler envaded Sark. Paramount-Lithoprint.

- ↑ Morison, Samuel Eliot History of United States Naval Operations in World War II p.306

- ↑ Crosswell, Daniel K. R. Beetle: The Life of General Walter Bedell Smith. University Press of Kentucky, 2010. p. 679. ISBN 9780813126494.

- ↑ The Churchill Centre: The End of the War in Europe Archived 19 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Sarnia Chérie (Guernsey anthem) - Sung on Liberation Day in 1945".

- ↑ Pether (1998), p. 7

- ↑ Hansard (Commons), vol. 430, col. 138

- ↑ The German Occupation of the Channel Islands, Cruickshank, London 1975 ISBN 0-19-285087-3

- ↑ The Times. 12 December 1945. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ War Profits Levy (Jersey) Law 1945

- ↑ War Profits (Guernsey) Law 1945

- ↑ Occupation Diary, Leslie Sinel, Jersey 1945

- ↑ Tabb, Peter. A peculiar occupation. Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0711031135.

- ↑ Cruickshank, Charles. The German Occupation of the Channel Islands. The Guernsey Press Co, Ltd.

- ↑ Ogier, Darryl. The Government and Law of Guernsey. States of Guernsey. ISBN 978-0-9549775-1-1.

- ↑ The Jews in the Channel Islands During the German Occupation 1940–1945, by Frederick Cohen, President of the Jersey Jewish Congregation, jerseyheritagetrust.org Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Noted in The Occupation, by Guy Walters, ISBN 0-7553-2066-2

- ↑ "Guernsey's Liberation Day story". Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ↑ Billet d'Etat Item IV, 2005 Archived 10 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Occupied.guernsey.net

- ↑ "Pubs1". Ciosjersey.org.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ Lempriére, Raoul. History of the Channel Islands. Robert Hale Ltd. p. 229. ISBN 978-0709142522.

- ↑ Visitguernsey.com – German Military Underground Hospital

- ↑ "La Piaeche d'la Libérâtiaon". Guernsey Museum and Art Gallery. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ Part 7 Twelve Pence to a Shilling King George VI

- ↑ "Jersey needs better World War II memorial, occupation society says". BBC. 8 February 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ Sthelier.je

- ↑ Liberationjersey.com

- ↑ Sebastian Scotney (15 May 2013). "Podcast: A Few Minutes with... Gwyneth Herbert". London Jazz News. London Jazz. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ↑ Gwyneth Herbert (2013). "Alderney Original Demo". SoundCloud. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ↑ Intonisfootsteps.co.uk

- ↑ The Blockhouse (1973), IMDb.

- ↑ http://www.lottyswar.com/

Bibliography

- Bell, William M. (2002), "Guernsey Occupied But Never Conquered", The Studio Publishing Services, ISBN 978-0952047933

- Bunting, Madeleine (1995), The Model Occupation: the Channel Islands under German rule, 1940–1945, London: Harper Collins, ISBN 0-00-255242-6

- Carr, Gillian; Sanders, Paul; Willmot, Louise. (2014). Protest, Defiance and Resistance in the Channel Islands: German Occupation, 1940-45. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 147250920X

- Cruickshank, Charles G. (1975), The German Occupation of the Channel Islands, The Guernsey Press, ISBN 0-902550-02-0

- Dunford-Slater, John (1953). Commando: Memoirs of a Fighting Commando in World War Two. Reprinted 2002 by Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-479-6

- Edwards, G. B. (1981), "The Book of Ebenezer le Page" (New York Review of Books Classics; 2006).

- Evans, Alice Alice, (2009), Guernsey Under Occupation: The Second World War Diaries of Violet Carey, The History Press, ISBN 978-1-86077-581-9

- Hamlin, John F. (1999), No 'Safe Haven': Military Aviation in the Channel Islands 1939–1945 Air Enthusiast # 83 September/October 1999 article pp. 6–15

- Hayes, John Crossley, teacher in charge of Vauvert school (1940–1945) and composer of Suite Guernesiaise, premiered in Guernsey October 2009. Documents of life in war time Guernsey at http://www.johncrossleyhayes.co.uk.

- Lewis, John (1983), "A Doctor's Occupation", New English Library Ltd; New edition edition (July 1, 1983), ISBN 978-0450056765

- Maughan, Reginald C. F. (1980), Jersey under the Jackboot, London: New English Library, ISBN 0-450-04714-8

- Money, June, (2011) Aspects of War, Channel Island Publishing, ISBN 978-1-905095-36-0

- Nettles, John (2012, Jewels & Jackboots, Channel Island Publishing & Jersey War Tunnels, ISBN 978-1-905095-38-4

- Pether, John (1998), The Post Office at War and Fenny Stratford Repeater Station, Bletchley Park Trust Reports, 12, Bletchley Park Trust

- Read, Brian A. (1995), No Cause for Panic – Channel Islands Refugees 1940–45, St Helier: Seaflower Books, ISBN 0-948578-69-6

- Sanders, Paul (2005), “The British Channel Islands under German Occupation 1940–1945” Jersey Heritage Trust / Société Jersiaise, ISBN 0953885836

- Shaffer, Mary Ann, and Barrows, Annie (2008), The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, ISBN 978-0-385-34099-1

- Tabb, Peter A peculiar occupation, Ian Allan Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7110-3113-5

- Winterflood, Herbert, Occupied Guernsey : July 1940-December 1942, Guernsey Press, ISBN 978-0-9539166-6-5

- Winterflood, Herbert, (2005), Occupied Guernsey 1943-1945, MSP Channel Islands, ISBN 978-0-9539116-7-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Channel Islands in World War II. |

- Channel Islands Occupation Society (Guernsey branch)

- Channel Islands Occupation Society (Jersey branch)

- Occupation at Visit Guernsey

- Jersey in Jail - Drawings by Edmund Blampied

- Jersey’s Occupation Story at Visit Jersey