Church of the Holy Sepulchre

| Church of the Holy Sepulchre | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Basic information | |

| Location | Old City of Jerusalem[1] |

| Geographic coordinates | 31°46′42.4″N 35°13′47.1″E / 31.778444°N 35.229750°ECoordinates: 31°46′42.4″N 35°13′47.1″E / 31.778444°N 35.229750°E |

| Affiliation | Christianity |

| Rite | Byzantine, Latin, Alexandrian, Armenian, Syrian Orthodox |

| Municipality | Jerusalem |

| Year consecrated | 13 September 335 |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Active |

| Architectural description | |

| Architect(s) | Nikolaos Ch. Komnenos Mitilenos (1810) |

| Architectural type | Church, Basilica |

| Architectural style | Romanesque, Baroque |

| Founder | Constantine the Great |

| Completed | 335 (demolished in 1009, rebuilt in 1048) |

| Capacity | 8,000 |

| Dome(s) | 3 |

| Materials | Stone, wood |

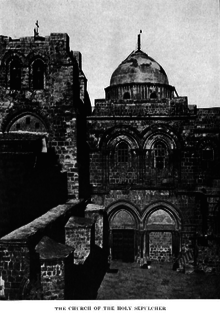

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre[2] (Latin: Ecclesia Sancti Sepulchri; also called the Church of the Resurrection or Church of the Anastasis by Orthodox Christians; Arabic: كنيسة القيامة, Kaneesat al-Qeyaamah; Hebrew: כנסיית הקבר, Knesiyat ha-Kever; Greek: Ναός της Αναστάσεως, Naos tes Anastaseos; Armenian: Սուրբ Յարութեան տաճար, Surb Harut’ian Tachar), is a church in the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem, a few steps away from the Muristan. The church contains, according to traditions dating back at least to the fourth century, the two holiest sites in Christianity: the site where Jesus of Nazareth was crucified,[3] known as "Calvary" (Calvāria) in Latin and "Golgotha" (Γολγοθᾶ, "Golgothâ") in Greek,[4] and Jesus's empty tomb, where he is said to have been buried and resurrected. The tomb is enclosed by the 18th-century shrine, called the Edicule (Aedicule).

Within the church proper are the last four (or, by some definitions, five) Stations of the Via Dolorosa, representing the final episodes of Jesus' Passion. The church has been a major Christian pilgrimage destination since its creation in the fourth century, as the traditional site of the Resurrection of Christ, thus its original Greek name, Church of the Anastasis.

Today the wider complex accumulated during the centuries around the Church of the Holy Sepulchre also serves as the headquarters of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem, while control of the church itself is shared between several Christian denominations and secular entities in complicated arrangements essentially unchanged for over 160 years, and some for much longer. The main denominations sharing property over parts of the church are the Greek Orthodox, Armenian Orthodox and Roman Catholic, and to a lesser degree the Egyptian Copts, Syriacs and Ethiopians. Meanwhile, Protestants including Anglicans have no permanent presence in the Church and they generally prefer the Garden Tomb, elsewhere in Jerusalem, as either the true place of Jesus' crucifixion and resurrection, or at least a more evocative site to commemorate those events.

History

Construction

According to Eusebius of Caesarea, the Roman emperor Hadrian in the 2nd century AD built a temple dedicated to the goddess Aphrodite in order to bury the cave in which Jesus had been buried.[5][6] The first Christian emperor, Constantine the Great, ordered in about 325/326 that the temple be replaced by a church.[7] During the building of the Church, Constantine's mother, Helena, is believed to have rediscovered the "True Cross", which tradition holds that when she found three crosses she tested each by having it held over a corpse and when the corpse rose up under one, that was the true cross,[8] and a tomb (although there are some discrepancies among authors).[5] Socrates Scholasticus (born c. 380), in his Ecclesiastical History, gives a full description of the discovery.[9]

Constantine's church was built as two connected churches over the two different holy sites, including a great basilica (the Martyrium visited by Egeria in the 380s), an enclosed colonnaded atrium (the Triportico) with the traditional site of Golgotha in one corner, and a rotunda, called the Anastasis ("Resurrection" in Greek), which contained the remains of a rock-cut room that Helena and Macarius identified as the burial site of Jesus.

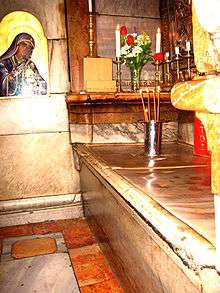

According to tradition, Constantine arranged for the rockface to be removed from around the tomb, without harming it, in order to isolate the tomb; in the centre of the rotunda is a small building called the Kouvouklion in Greek[10] or the Aedicula in Latin,[11] which encloses this tomb. The remains are completely enveloped by a marble sheath placed some 500 years before to protect the ledge from Ottoman attacks. However, there are several thick window wells extending through the marble sheath, from the interior to the exterior that are not marble clad. They appear to reveal an underlying limestone rock, which may be part of the original living rock of the tomb.

The church was built starting in 325/326, and was consecrated on 13 September 335. From pilgrim reports it seems that the chapel housing the tomb of Jesus was freestanding at first, and that the Rotunda was only erected around the chapel in the 380s.

Each year, the Eastern Orthodox Church celebrates the anniversary of the consecration of the Church of the Resurrection (Holy Sepulchre) on 13 September.[12]

Damage and destruction

This building was damaged by fire in May of 614 when the Sassanid Empire, under Khosrau II, invaded Jerusalem and captured the True Cross. In 630, the Emperor Heraclius restored it and rebuilt the church after recapturing the city. After Jerusalem was captured by the Arabs, it remained a Christian church, with the early Muslim rulers protecting the city's Christian sites. A story reports that the Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab visited the church and stopped to pray on the balcony; but at the time of prayer, he turned away from the church and prayed outside. He feared that future generations would misinterpret this gesture, taking it as a pretext to turn the church into a mosque. Eutychius added that Umar wrote a decree prohibiting Muslims from praying at this location. The building suffered severe damage due to an earthquake in 746.

Early in the ninth century, another earthquake damaged the dome of the Anastasis. The damage was repaired in 810 by Patriarch Thomas. In the year 841, the church suffered a fire. In 935, the Orthodox Christians prevented the construction of a Muslim mosque adjacent the Church. In 938, a new fire damaged the inside of the basilica and came close to the rotunda. In 966, due to a defeat of Muslim armies in the region of Syria, a riot broke out and was followed by reprisals. The basilica was burned again. The doors and roof were burnt, and the Patriarch John VII was murdered.

On 18 October 1009, Fatimid caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah ordered the complete destruction of the church as part of a more general campaign against Christian places of worship in Palestine and Egypt.[13] The damage was extensive, with few parts of the early church remaining.[14] Christian Europe reacted with shock and expulsions of Jews (for example, Cluniac monk Rodulfus Glaber blamed the Jews, with the result that Jews were expelled from Limoges and other French towns) and an impetus to later Crusades.[15][16]

Reconstruction

In wide-ranging negotiations between the Fatimids and the Byzantine Empire in 1027–8, an agreement was reached whereby the new Caliph Ali az-Zahir (Al-Hakim's son) agreed to allow the rebuilding and redecoration of the Church.[17] The rebuilding was finally completed with the financing at a huge expense by Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos and Patriarch Nicephorus of Constantinople in 1048.[18] As a concession, the mosque in Constantinople was re-opened and sermons were to be pronounced in az-Zahir's name. Muslim sources say a by-product of the agreement was the recanting of Islam by many Christians who had been forced to convert under Al-Hakim's persecutions. In addition, the Byzantines, while releasing 5,000 Muslim prisoners, made demands for the restoration of other churches destroyed by Al-Hakim and the re-establishment of a Patriarch in Jerusalem. Contemporary sources credit the emperor with spending vast sums in an effort to restore the Church of the Holy Sepulchre after this agreement was made.[17] Despite the Byzantines spending vast sums on the project, "a total replacement was far beyond available resources. The new construction was concentrated on the rotunda and its surrounding buildings: the great basilica remained in ruins."[14] The rebuilt church site consisted of "a court open to the sky, with five small chapels attached to it."[19] The chapels were to the east of the court of resurrection, where the wall of the great church had been. They commemorated scenes from the passion, such as the location of the prison of Christ and of his flagellation, and presumably were so placed because of the difficulties of free movement among shrines in the streets of the city. The dedication of these chapels indicates the importance of the pilgrims' devotion to the suffering of Christ. They have been described as 'a sort of Via Dolorosa in miniature'... since little or no rebuilding took place on the site of the great basilica. Western pilgrims to Jerusalem during the eleventh century found much of the sacred site in ruins."[14] Control of Jerusalem, and thereby the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, continued to change hands several times between the Fatimids and the Seljuk Turks (loyal to the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad) until the arrival of the Crusaders in 1099.[20]

Crusader period

Many historians maintain that the main concern of Pope Urban II, when calling for the First Crusade, was the threat to Constantinople from the Turkish invasion of Asia Minor in response to the appeal of Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos. Historians agree that the fate of Jerusalem and thereby the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was of concern if not the immediate goal of papal policy in 1095. The idea of taking Jerusalem gained more focus as the Crusade was underway. The rebuilt church site was taken from the Fatimids (who had recently taken it from the Abassids) by the knights of the First Crusade on 15 July 1099.[14]

1. The Holy Sepulchre

2. The Dome of the Rock

3. Ramparts

The First Crusade was envisioned as an armed pilgrimage, and no crusader could consider his journey complete unless he had prayed as a pilgrim at the Holy Sepulchre. Crusader Prince Godfrey of Bouillon, who became the first crusader monarch of Jerusalem, decided not to use the title "king" during his lifetime, and declared himself "Advocatus Sancti Sepulchri" ("Protector [or Defender] of the Holy Sepulchre"). By the crusader period, a cistern under the former basilica was rumoured to have been the location where Helena had found the True Cross, and began to be venerated as such; although the cistern later became the "Chapel of the Invention of the Cross," there is no evidence of the rumour before the 11th century, and modern archaeological investigation has now dated the cistern to 11th century repairs by Monomachos.

According to the German clergyman and orient pilgrim Ludolf von Sudheim, the keys of the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre were in hands of the "ancient Georgians" and the food, alms, candles and oil for lamps were given them by the pilgrims in the south door of the church.[21]

William of Tyre, chronicler of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, reports on the renovation of the Church in the mid-12th century. The crusaders investigated the eastern ruins on the site, occasionally excavating through the rubble, and while attempting to reach the cistern, they discovered part of the original ground level of Hadrian's temple enclosure; they decided to transform this space into a chapel dedicated to Helena (the Chapel of Saint Helena), widening their original excavation tunnel into a proper staircase. The crusaders began to refurnish the church in a Romanesque style and added a bell tower.[22] These renovations unified the small chapels on the site and were completed during the reign of Queen Melisende in 1149, placing all the Holy places under one roof for the first time. The church became the seat of the first Latin Patriarchs, and was also the site of the kingdom's scriptorium. The church was lost to Saladin,[22] along with the rest of the city, in 1187, although the treaty established after the Third Crusade allowed for Christian pilgrims to visit the site. Emperor Frederick II (r. 1220–50) regained the city and the church by treaty in the 13th century while he himself was under a ban of excommunication, with the curious consequence that the holiest church in Christianity was laid under interdict. The church seems to have been largely in Greek Orthodox Patriarch Athanasius II of Jerusalem's hands, ca. 1231–47, during the Latin control of Jerusalem.[23] Both city and church were captured by the Khwarezmians in 1244.[22]

Later periods

The Franciscan friars renovated it further in 1555, as it had been neglected despite increased numbers of pilgrims. The Franciscans rebuilt the Aedicule, extending the structure to create an ante-chamber.[24] After the renovation of 1555, control of the church oscillated between the Franciscans and the Orthodox, depending on which community could obtain a favorable "firman" from the "Sublime Porte" at a particular time, often through outright bribery, and violent clashes were not uncommon. There was no agreement about this question, although it was discussed at the negotiations to the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699.[25] In 1767, weary of the squabbling, the "Porte" issued a "firman" that divided the church among the claimants.

A fire severely damaged the structure again in 1808, causing the dome of the Rotunda to collapse and smashing the Edicule's exterior decoration. The Rotunda and the Edicule's exterior were rebuilt in 1809–1810 by architect Nikolaos Ch. Komnenos of Mytilene in the then current Ottoman Baroque style. The fire did not reach the interior of the Aedicule, and the marble decoration of the Tomb dates mainly to the 1555 restoration, although the interior of the ante-chamber, now known as the "Chapel of the Angel," was partly rebuilt to a square ground-plan, in place of the previously semi-circular western end. Another decree in 1853 from the sultan solidified the existing territorial division among the communities and set a "status quo" for arrangements to "remain forever," causing differences of opinion about upkeep and even minor changes,[26] including disagreement on the removal of the "Immovable Ladder," an exterior ladder under one of the windows; this ladder has remained in the same position since then.

The cladding of red marble applied to the Aedicule by Komnenos has deteriorated badly and is detaching from the underlying structure; since 1947 it has been held in place with an exterior scaffolding of iron girders installed by the British authorities. A careful renovation is undergoing, funded by a $4 million gift from King Abdullah II of Jordan and a $1.3-million gift from Mica Ertegun.[27]

The current dome dates from 1870, although it was restored between 1994–1997, as part of extensive modern renovations to the church which have been ongoing since 1959. During the 1970–1978 restoration works and excavations inside the building, and under the nearby Muristan, it was found that the area was originally a quarry, from which white meleke limestone was struck.[28] To the east of the Chapel of Saint Helena, the excavators discovered a void containing a 2nd-century drawing of a Roman ship, two low walls which supported the platform of Hadrian's 2nd-century temple, and a higher 4th-century wall built to support Constantine's basilica.[24][29] After the excavations of the early 1970s, the Armenian authorities converted this archaeological space into the Chapel of Saint Vartan, and created an artificial walkway over the quarry on the north of the chapel, so that the new Chapel could be accessed (by permission) from the Chapel of Saint Helena.[29]

In 2016, restoration works were performed in the Edicule. For the first time since at least 1555, marble cladding which protected the estimated burial bed of Jesus from vandalism and souvenir takers[30] was removed.[31][32] When the cladding was first removed on October 26, an initial inspection by the National Technical University of Athens team showed only a layer of fill material underneath. By the night of October 28, the original limestone burial bed was revealed intact. This suggested that the tomb location has not changed through time and confirmed the existence of the original limestone cave walls within the Edicule.[31] The tomb was resealed shortly thereafter.[31]

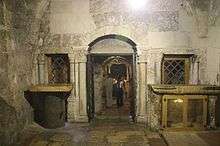

Entrance and parvis

The entrance to the church, a single door in the south transept—through the crusader façade—is found past a group of streets winding through the outer Via Dolorosa, by way of a local souq in the Muristan. This narrow way of access to such a large structure has proven to be hazardous at times. For example, when a fire broke out in 1840, dozens of pilgrims were trampled to death.[33]

Historically, two large, arched doors allowed access to the church. However, only the left-hand entrance is currently accessible, as the right door has long since been bricked up. These entrances are located in the parvis of a larger courtyard, or plaza.

Also located along the parvis are a few smaller structures and openings:

- Chapel of the Franks—a blue-domed Roman Catholic crusader chapel dedicated to Our Lady of Sorrows, which once provided exclusive access to Calvary. The chapel marks the 10th Station of the Cross (the stripping of Jesus' garments).

- A Greek Orthodox oratory and chapel, just beneath the Chapel of the Franks, dedicated to St. Mary of Egypt.

- Various entrances to Armenian, Greek Orthodox, and Ethiopian Orthodox chapels.

- A small Greek Orthodox monastery, known as Gethsemane Metoxion, located to the side of the church.

- The tomb of Philippe D'Aubigny (Philip Daubeny, d. 1236)—a knight, tutor, and royal councilor to King Henry III of England and signer of the Magna Carta—one of the few tombs of crusaders and other Europeans not removed from the Church after the Muslim recapture of Jerusalem in the 12th century, sheltered by a wooden trapdoor in the parvise. A stone marker was placed on his tomb in 1925.

Broken columns—once forming part of an arcade—flank the church's front, which is covered in crusader graffiti mostly consisting of crosses. In the 13th century, the tops of the columns were removed and sent to Mecca by the Khwarezmids.

The church's bell tower is located to the left of the façade. It is currently almost half its original size.[34]

The historic Immovable Ladder stands beneath a window on the façade.

Calvary (Golgotha)

On the south side of the altar, via the ambulatory, is a stairway climbing to Calvary (Golgotha), traditionally regarded as the site of Jesus' crucifixion and the most lavishly decorated part of the church. The main altar there belongs to the Greek Orthodox, which contains the Rock of Calvary (12th Station of the Cross). The rock can be seen under glass on both sides of the altar, and beneath the altar there is a hole said to be the place where the cross was raised. Due to the significance of this, it is the most visited site in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The Roman Catholics (Franciscans) have an altar to the side, the Chapel of the Nailing of the Cross (11th Station of the Cross). On the left of the altar, towards the Eastern Orthodox chapel, there is a statue of Mary, believed by some to be miraculous (the 13th Station of the Cross, where Jesus' body was removed from the cross and given to his family).

Beneath the Calvary and the two chapels there, on the main floor, there is the Chapel of Adam. According to tradition, Jesus was crucified over the place where Adam's skull was buried. According to some, at the crucifixion, the blood of Christ ran down the cross and through the rocks to fill the skull of Adam.[35] The Rock of Calvary appears cracked through a window on the altar wall, with the crack traditionally claimed to be caused by the earthquake that occurred when Jesus died on the cross, while some scholars claim it to be the result of quarrying against a natural flaw in the rock.[36]

Stone of Anointing

Just inside the entrance to the church is the Stone of Anointing (also Stone of the Anointing or Stone of Unction), which tradition believes to be the spot where Jesus' body was prepared for burial by Joseph of Arimathea. However, this tradition is only attested since the crusader era (notably by the Italian Dominican pilgrim Riccoldo da Monte di Croce in 1288), and the present stone was only added in the 1810 reconstruction.[24]

The wall behind the stone is defined by its striking blue balconies and tau cross-bearing red banners (depicting the insignia of the Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre), and is decorated with lamps. The modern mosaic along the wall depicts the anointing of Jesus' body.

The wall was a temporary addition to support the arch above it, which had been weakened after the damage in the 1808 fire; it blocks the view of the rotunda, separates the entrance from the Catholicon, sits on top of the now-empty and desecrated graves of four 12th-century crusader kings—including Godfrey of Bouillon and Baldwin I of Jerusalem—and is no longer structurally necessary. There is a difference of opinion as to whether it is the 13th Station of the Cross, which others identify as the lowering of Jesus from the cross and locate between the 11th and 12th stations up on Calvary.

The lamps that hang over the Stone of Unction, adorned with cross-bearing chain links, are contributed by Armenians, Copts, Greeks and Latins.

Immediately to the left of the entrance is a bench that has traditionally been used by the church's Muslim doorkeepers, along with some Christian clergy, as well as electrical wiring. To the right of the entrance is a wall along the ambulatory containing, to the very right, the staircase leading to Golgatha. Further along the same wall is the entrance to the Chapel of Adam.

Rotunda and Aedicule

The Rotunda is located in the centre of the Anastasis, beneath the larger of the church's two domes. In the center of the Rotunda is the chapel called the Aedicule, which contains the Holy Sepulchre itself. The Aedicule has two rooms, the first holding the Angel's Stone, which is believed to be a fragment of the large stone that sealed the tomb; the second is the tomb itself. Possibly due to the fact that pilgrims laid their hands on the tomb and/or to prevent eager pilgrims from removing bits of the original rock as souvenirs, a marble plaque was placed in the fourteenth century on the tomb to prevent further damage to the tomb.[37]

Under the status quo, the Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Armenian Apostolic Churches all have rights to the interior of the tomb, and all three communities celebrate the Divine Liturgy or Holy Mass there daily. It is also used for other ceremonies on special occasions, such as the Holy Saturday ceremony of the Holy Fire led by the Greek Orthodox Patriarch (with the participation of the Coptic and Armenian patriarchs).[38] To its rear, in a chapel constructed of iron latticework upon a stone base semicircular in plan, lies the altar used by the Coptic Orthodox. Historically, the Georgians also retained the key to the Aedicule.[39][40][41]

Beyond that to the rear of the Rotunda is a rough-hewn chapel containing an opening to a chamber cut from the rock, from which several kokh-tombs radiate. Although this space was discovered recently, and contains no identifying marks, many Christians believe it to be the tomb of Joseph of Arimathea, and it is where the Syriac Orthodox celebrate their Liturgy on Sundays. To the right of the Sepulchre on the northwestern edge of the Rotunda is the Chapel of the Apparition, which is reserved for Roman Catholic use.

Catholicon and Ambulatory

- The Catholicon – On the east side opposite the Rotunda is the Crusader structure housing the main altar of the Church, today the Greek Orthodox catholicon. The second, smaller dome sits directly over the centre of the transept crossing of the choir where the compas, an omphalos once thought to be the center of the world (associated to the site of the Crucifixion and the Resurrection), is situated. Since 1996 this dome is topped by the monumental Golgotha Crucifix which the Greek Patriarch Diodoros I of Jerusalem consecrated. It was at the initiative of Gustav Kühnel to erect a new crucifix at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem that would not only be worthy of the singularity of the site, but that would also become a symbol of the efforts of unity in the community of Christian faith.[42]

East of this is a large iconostasis demarcating the Orthodox sanctuary before which is set the throne of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem on the south side facing the throne of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch on the north side.

- Prison of Christ – In the north-east side of the complex there is The Prison of Christ, alleged by the Franciscans to be where Jesus was held. The Greek Orthodox allege that the real place that Jesus was held was the similarly named Prison of Christ, in their Monastery of the Praetorium, located near the Church of Ecce Homo, at the first station on the Via Dolorosa. The Armenians regard a recess in the Monastery of the Flagellation, a building near the second station on the Via Dolorosa, as the Prison of Christ. A cistern among the ruins near the Church of St. Peter in Gallicantu is also alleged to have been the Prison of Christ.

Further to the east in the ambulatory are three chapels (from south to north):

- Greek Chapel of Saint Longinus – The Orthodox Greek chapel is dedicated to Saint Longinus.

- Armenian Chapel of Division of Robes

- Greek Chapel of the Derision – the southernmost chapel in the ambulatory.

Armenian compound

- Chapel of Saint Helena – between the first two chapels are stairs descending to the Chapel of Saint Helena.

- Chapel of Saint Vartan – on the north side of the Chapel of Saint Helena is an ornate wrought iron door, beyond which a raised artificial platform affords views of the quarry, and which leads to the Chapel of Saint Vartan. The latter chapel contains archaeological remains from Hadrian's temple and Constantine's basilica. These areas are usually closed.

- Chapel of the Invention of the Holy Cross – another set of 22 stairs from the Chapel of Saint Helena leads down to the Roman Catholic Chapel of the Invention of the Holy Cross, believed to be the place where the True Cross was found.

North of the Aedicule

- The Franciscan Chapel of St. Mary Magdalene – The chapel indicates the place where Mary Magdalene met Jesus after his resurrection.[43]

- The Franciscan Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament (or Chapel of the Apparition) – in memory of Jesus' meeting with his mother after the Resurrection.[43]

South of the Aedicule

The three Greek Orthodox chapels of St. James the Just, St. John the Baptist and of the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste, south of the rotunda and on the west side of the front courtyard originally formed the baptistery complex of the Constantinean church. The southernmost chapel was the vestibule, the middle chapel the actual baptistery, and the north chapel the chamber in which the patriarch chrismated the newly baptized before leading them into the rotunda north of this complex.

Syriac Compound

- The Syriac Orthodox Chapel of Saint Joseph of Arimathea and Saint Nicodemus. On Sundays and feast days it is furnished for the celebration of Mass.

On the far side of the chapel is the low entrance to two complete 1st-century Jewish tombs. Since Jews always buried their dead outside the city, this proves that the Holy Sepulchre site was outside the city walls at the time of the crucifixion. There is a tradition that Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus were buried here.

Status quo

The Sultan's firman (decree) of 1853, known as the "status quo", pinned down the now permanent statutes of property and the regulations concerning the roles of the different denominations and other custodians.

The primary custodians are the Greek Orthodox, Armenian Apostolic, and Roman Catholic Churches, with the Greek Orthodox Church having the lion's share. In the 19th century, the Coptic Orthodox, the Ethiopian Orthodox and the Syriac Orthodox acquired lesser responsibilities, which include shrines and other structures in and around the building. Times and places of worship for each community are strictly regulated in common areas. The Greek Orthodox act through the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate as well as through the Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre. The Roman Catholics act through the Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land.

The establishment of the 1853 status quo did not halt the violence, which continues to break out every so often even in modern times. On a hot summer day in 2002, a Coptic monk moved his chair from its agreed spot into the shade. This was interpreted as a hostile move by the Ethiopians, and eleven were hospitalized after the resulting fracas.[44]

In another incident in 2004, during Orthodox celebrations of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, a door to the Franciscan chapel was left open. This was taken as a sign of disrespect by the Orthodox and a fistfight broke out. Some people were arrested, but no one was seriously injured.[45]

On Palm Sunday, in April 2008, a brawl broke out when a Greek monk was ejected from the building by a rival faction. Police were called to the scene but were also attacked by the enraged brawlers.[46] On Sunday, 9 November 2008, a clash erupted between Armenian and Greek monks during celebrations for the Feast of the Cross.[47][48]

Under the status quo, no part of what is designated as common territory may be so much as rearranged without consent from all communities. This often leads to the neglect of badly needed repairs when the communities cannot come to an agreement among themselves about the final shape of a project. Just such a disagreement delayed the renovation of the edicule, but also where any change in the structure might result in a change to the status quo, disagreeable to one or more of the communities. After the Greek Orthodox Church, the Roman Catholic Church and the Armenian Orthodox Church agreed in 1958 to restore the edicule, nearly 50 years of discussion ensued before restoration commenced.[49]

A less grave sign of this state of affairs is located on a window ledge over the church's entrance. A wooden ladder was placed there at some time before 1852, when the status quo defined both the doors and the window ledges as common ground. This ladder, the "Immovable Ladder", remains to this day, in almost exactly the same position it occupied in century-old photographs and engravings.[50][51] An engraving by David Roberts in 1839 also shows the same ladder in the same position.[52]

No one controls the main entrance. In 1192, Saladin assigned door keeping responsibilities to the Muslim Nuseibeh family. The wooden doors that compose the main entrance are the original, highly carved doors.[53] The Joudeh Al-Goudia family were entrusted as custodian to the keys of the Holy Sepulchre by Saladin in 1187. This arrangement has persisted into modern times.

Connection to Temple of Aphrodite

The site of the Church had been a temple of Aphrodite before Constantine's edifice was built. Hadrian's temple had actually been located there because it was the junction of the main north-south road with one of the two main east-west roads and directly adjacent to the forum (which is now the location of the (smaller) Muristan); the forum itself had been placed, as is traditional in Roman towns, at the junction of the main north-south road with the (other) main east-west road (which is now El-Bazar/David Street). The temple and forum together took up the entire space between the two main east-west roads (a few above-ground remains of the east end of the temple precinct still survive in the Alexander Nevsky Church complex of the Russian Mission in Exile).

From the archaeological excavations in the 1970s, it is clear that construction took over most of the site of the earlier temple enclosure and that the Triportico and Rotunda roughly overlapped with the temple building itself; the excavations indicate that the temple extended at least as far back as the Aedicule, and the temple enclosure would have reached back slightly further. Virgilio Canio Corbo, a Franciscan priest and archaeologist, who was present at the excavations, estimated from the archaeological evidence that the western retaining wall, of the temple itself, would have passed extremely close to the east side of the supposed tomb; if the wall had been any further west any tomb would have been crushed under the weight of the wall (which would be immediately above it) if it had not already been destroyed when foundations for the wall were made.[54]

Other archaeologists have criticized Corbo's reconstructions. Dan Bahat, the former city archaeologist of Jerusalem, regards them as unsatisfactory, as there is no known temple of Aphrodite matching Corbo's design, and no archaeological evidence for Corbo's suggestion that the temple building was on a platform raised high enough to avoid including anything sited where the Aedicule is now; indeed Bahat notes that many temples to Aphrodite have a rotunda-like design, and argues that there is no archaeological reason to assume that the present rotunda was not based on a rotunda in the temple previously on the site.[55]

Location

The Bible describes Jesus's tomb as being outside the city wall,[56] as was normal for burials across the ancient world, which were regarded as unclean.[57] Today, the site of the Church is within the current walls of the old city of Jerusalem. It has been well documented by archaeologists that in the time of Jesus, the walled city was smaller and the wall then was to the east of the current site of the Church. In other words, the city had been much narrower in Jesus' time, with the site then having been outside the walls; since Herod Agrippa (41–44) is recorded by history as extending the city to the north (beyond the present northern walls), the required repositioning of the western wall is traditionally attributed to him as well.

The area immediately to the south and east of the sepulchre was a quarry and outside the city during the early 1st century as excavations under the Lutheran Church of the Redeemer across the street demonstrated.

The church is a part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site Old City of Jerusalem.

Influence

From the 9th century, the construction of churches inspired in the Anastasis was extended across Europe.[58] One example is Santo Stefano in Bologna, Italy, an agglomeration of seven churches recreating shrines of Jerusalem.

Several churches and monasteries in Europe, for instance, in Germany and Russia, and at least one church in the United States have been modeled on the Church of the Resurrection, some even reproducing other holy places for the benefit of pilgrims who could not travel to the Holy Land. They include the Heiliges Grab of Görlitz, constructed between 1481 and 1504,the New Jerusalem Monastery in Moscow Oblast, constructed by Patriarch Nikon between 1656 and 1666, and Mount St. Sepulchre Franciscan Monastery built by the Franciscans in Washington, DC in 1898.

In fiction

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre features prominently in the 2016 crypto-thriller The Apocalypse Fire by Dominic Selwood.

See also

- Art of the Crusades

- Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre

- Burial places of founders of world religions

- Canons Regular of the Holy Sepulchre

- Constantine I and Christianity

- Christianity in Israel

- Early Christian art and architecture

- Fathers of the Holy Sepulchre

- Garden Tomb

- History of the Orthodox Church

- History of Roman and Byzantine domes

- List of oldest church buildings

- Monza ampullae

- Order of the Holy Sepulchre

- Palestinian Christians

- Rock-cut tombs in ancient Israel

- Status quo (Holy Land sites)

- Talpiot Tomb

References

- ↑ The old town area is de jure in the Palestinian territories, but the power over the region is de facto exercised by the State of Israel.

- ↑ In American English also spelled Sepulcher. Also called the Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre.

- ↑

McMahon, Arthur L. (1913). "Holy Sepulchre". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

McMahon, Arthur L. (1913). "Holy Sepulchre". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ "Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem". Jerusalem: Sacred-destinations.com. 21 February 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- 1 2 NPNF2-01. Eusebius Pamphilius: Church History, Life of Constantine, Oration in Praise of Constantine. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. 13 July 2005. Retrieved 2014-09-19.

Though Eusebius's account makes no mention of Helena's presence at the excavation, nor of the finding of the cross but only the tomb. According to Eusebius, the tomb exhibited "a clear and visible proof" that it was the tomb of Jesus.

- ↑ Pringle, Denys (2007). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0521390361. Retrieved 2014-09-19. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ The Pilgrim of Bordeaux reports in 333: "There, at present, by the command of the Emperor Constantine, has been built a basilica, that is to say, a church of wondrous beauty". Itinerarium Burdigalense, page 594

- ↑ ″William R. Cook of State University of New York, lecture series″

- ↑ "NPNF2-02. Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. 13 July 2005. Retrieved 2014-09-19.

- ↑ Kουβούκλιον; Modern Greek for small compartment

- ↑ English aedicule or edicule, the Latin diminutive of aedes, "house", meaning "small house" or "shrine"

- ↑ "Commemoration of the Founding of the Church of the Resurrection (Holy Sepulchre) at Jerusalem". Orthodox Church in America. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ↑ Adémar de Chabannes recorded that the church of Saint George at Lydda 'with many other churches of the saints' had been attacked, and the 'basilica of the Lord's Sepulchre destroyed down to the ground'. ...The Christian writer Yahya ibn Sa'id reported that everything was razed 'except those parts which were impossible to destroy or would have been too difficult to carry away'." Morris 2005

- 1 2 3 4 Morris 2005

- ↑ Bokenkotter, Thomas (2004). A Concise History of the Catholic Church. Doubleday. p. 155. ISBN 0-385-50584-1.

- ↑ MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2009-09-24). A History of Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 9780141957951.

- 1 2 Lev, Yaacov (July 1991). State and Society in Fatimid Egypt. Leiden; New York: E.J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09344-7. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Foakes-Jackson, Frederick John (1921). An Introduction to the History of Christianity, A. D. 590–1314. London: Macmillan.

- ↑ Fergusson, James (1865). A History of Architecture in All Countries. London: J. Murray.

- ↑ Gold, Dore (29 January 2007). The Fight for Jerusalem: Radical Islam, the West, and the Future of the Holy City. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing. ISBN 1-59698-029-X.

- ↑ Venetian Adventurer: The Life and Times of Marco Polo, p88

- 1 2 3 Pilgrimages and Pilgrim shrines in Palestine and Syria after 1095, Henry L. Savage, ''A History of the Crusades: The Art and Architecture of the Crusader States, Volume IV, ed. Kenneth M. Setton and Harry W. Hazard, (University of Wisconsin Press, 1977), 37.

- ↑ Pringle, Denys (1993). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: Volume 3, The City of Jerusalem: A Corpus. Cambridge University Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-0-521-39038-5.

- 1 2 3 Murphy-O'Connor, Jerome (February 1998). The Holy Land. Oxford University Press. pp. 56, 59. ISBN 978-0191528675. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Mailáth, János Nepomuk Jozsef (1848). Geschichte der europäischen Staaten, Geschichte des östreichischen Kaiserstaates [History of the European states, history of Austrian Imperial State]. 4. Hamburg: F. Perthes. p. 262.

- ↑ Cohen, Raymond (May 2009). "The Church of the Holy Sepulchre: A Work in Progress". The Bible and Interpretation. Retrieved 2014-09-19.

- ↑ Kristin Romey (26 October 2016). "Exclusive: Christ's Burial Place Exposed for First Time in Centuries". National Geographic. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ↑ Hesemann, Michael (1999). Die Jesus-Tafel (in German). Freiburg. p. 170. ISBN 3-451-27092-7.

- 1 2 Lancaster, James E. (1998). "Finding the Keys to the Chapel of St. Vartan". Jim Lancaster's Web Space. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

the height difference can be easily seen; the yellowish wall on the left is the 4th century wall, the pinkish wall on the right is the 2nd century wall.

- ↑ http://cnsnews.com/commentary/eric-metaxas/history-revealed-jesuss-tomb-discovered-church-holy-sepulchre-empty

- 1 2 3 Kristin Romey (31 October 2016). "Unsealing of Christ's Reputed Tomb Turns Up New Revelations". National Geographic. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ↑ Stephanie Pappas (31 October 2016). "Original Bedrock of Jesus' Tomb Revealed in New Images". Live Science. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ↑ LoLordo, Ann (28 June 1999). "Trouble in a holy place". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2014-09-19.

- ↑ http://www.sepulchre.custodia.org/default.asp?id=4100

- ↑ William R. Cook of State University of New York, lecture series

- ↑ "The Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulcher". Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Archived from the original on 24 May 2008. Retrieved 2014-09-19.

- ↑ "Jesus' Burial Tomb Uncovered: Here's What Scientists Saw Inside". 2016-10-31. Retrieved 2016-10-31.

- ↑ "Miracle of Holy Fire which happens every year". Holyfire.org. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ↑ Janin, Raymond (1913). Échos d'Orient [Echos of the Orient]. 16. Institut français d'études byzantines. p. 35.

- ↑ DeSandoli, Sabino (1986). The Church of Holy Sepulchre: Keys, Doors, Doorkeepers. Franciscian Press. p. 47.

- ↑ Jeffery, George (1919). A Brief Description of the Holy Sepulchre Jerusalem and Other Christian Churches in the Holy City: With Some Account of the Medieval Copies of the Holy Sepulchre Surviving in Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 69. Retrieved 2014-09-19.

- ↑ "The Cross of Golgotha". Michael Hammers. 24 June 2014. Retrieved 2014-09-19.

- 1 2 "The Franciscans at the Holy Sepulchre". The Franciscans of the Holy Land. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ↑ Armstrong, Chris (1 July 2002). "Christian History Corner: Divvying up the Most Sacred Place". Christianity Today. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ↑ Fisher-Ilan, Allyn (28 September 2004). "Punch-up at tomb of Jesus". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2014-09-19.

- ↑ El Deeb, Sarah (21 April 2008). "Christians brawl at Jesus' tomb". San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. Retrieved 2014-09-19.

- ↑ "Riot police called as monks clash in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre". The Times. London. 10 November 2008. Retrieved 2014-09-19. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ O'Laughlin, Toni (10 November 2008). "The monks who keep coming to blows in Jerusalem". The Guardian. Retrieved 2014-09-19.

- ↑ Pappas, Stephanie (2016-10-27). "Jesus' Tomb Opened for First Time in Centuries". Live Science. Retrieved 2016-10-31.

- ↑ "Holy Sepulchre Ladder". Coastdaylight.com. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ↑ "Who moved thy ladder?". Danny the Digger. 2010. Retrieved 2014-09-19.

An unusual and rare location of the ladder was documented by an Israeli tour guide in February 2009

- ↑ "Entrance to the holy sepulchre; title page, vol. 1". Library of Congress. 1842. Retrieved 2014-09-19.

- ↑ William R. Cook of University of New York, lecture series

- ↑ Corbo, Virgilio (1981). Il Santo Sepolcro di Gerusalemme [The Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem] (in Italian). Franciscan Press.

- ↑ Bahat, Dan (May–June 1986). "Does the Holy Sepulchre Church Mark the Burial of Jesus?". Biblical Archaeology Review. Retrieved 2014-09-19. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ for example, Hebrews 13:12

- ↑ Toynbee, Jocelyn M. C. Death and Burial in the Roman World, pp. 48–49, JHU Press. 1996. ISBN 0-8018-5507-1. An exception in the Classical World were the Lycians of Anatolia. There are also the Egyptian mortuary-temples, where the object of worship was the deified royal person entombed, but Egyptian temples to the major gods contained no burials.

- ↑ Monastero di Santo Stefano: Basilica Santuario Santo Stefano: Storia, Bologna.

Bibliography

- Coüasnon, Charles (1974). The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. London: Oxford University Press for the British Academy. ISBN 0-19-725938-3.

Further reading

- Biddle, Martin (25 February 1999). The Tomb of Christ. Scarborough: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-1926-4.

- Biddle, Martin; Seligman, Jon; Tamar, Winter & Avni, Gideon (7 July 2000). The Church of the Holy Sepulchre. New York: Rizzoli in cooperation with Israel Antiquities Authority, distributed by St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-8478-2282-6.

- Gibson, Shimon; Taylor, Joan E. (1994). Beneath the Church of the Holy Sepulchre Jerusalem: The archaeology and early history of traditional Golgotha. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. ISBN 0-903526-53-0.

- Cohen, Raymond (10 March 2008). Saving the Holy Sepulchre: How Rival Christians Came Together to Rescue Their Holiest Shrine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-518966-3. (subscription required (help)).

- Bowman, Glenn (16 September 2011). ""In Dubious Battle on the Plains of Heav'n": The Politics of Possession in Jerusalem's Holy Sepulchre". University of Kent.

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed. (1979). Age of spirituality: late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0870991790.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Church of the Holy Sepulchre. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- OrthodoxWiki (article)

- Sacred Destinations (article, interactive plan, photo gallery)

- The Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (article and photos)

- Virtual Tour (Church of the Holy Sepulchre Virtual Tour)

- Private Virtual Tour (Church of the Holy Sepulchre Private Virtual Tour)

Custodians

- Franciscan Custody in the Holy Land (Roman Catholic custodians)

- The Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre (Greek Orthodox custodians)

- St. James Brotherhood (Armenian custodians)

- The Joudeh Family (Muslim Custodian of the keys of the Holy Sepulchre)

- Nuseibeh family (Muslim Holy Sepulchre Door Keepers)

- Homily of John Paul II in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre