History of printing in East Asia

The history of printing in East Asia starts with the use of woodblock printing on cloth during the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) and later paper (in Imperial Court as early as the 1st century, or around 80 AD), and continued with the invention of wooden movable type by East Asian artisans in Song China by the 11th century. Use of woodblock printing quickly spread to other East Asian countries. While the Chinese used only clay and wood movable type at first, use of metal movable type was pioneered in Korea by the 13th century. The Western-style printing press became known in East Asia by the 16th century but was not fully adopted until centuries later.

Woodblock printing

Traditionally, there have been two main printing techniques in Asia: woodblock printing (xylography) and moveable type printing. In the woodblock technique, ink is applied to letters carved upon a wooden board, which is then pressed onto paper. With moveable type, the board is assembled using different lettertypes, according to the page being printed. Wooden printing was used in the East from the 8th century onwards, and moveable metal type came into use during the 12th century.[1]

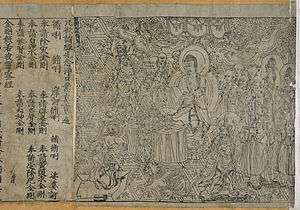

The earliest specimen of woodblock printing on paper, whereby individual sheets of paper were pressed into wooden blocks with the text and illustrations carved into them, was discovered in 1974 in an excavation of Xi'an (then called Chang'an, the capital of Tang China), Shaanxi, China.[2] It is a dharani sutra printed on hemp paper and dated to 650 to 670 AD, during the Tang Dynasty (618-907).[2] Another printed document dating to the early half of the Chinese Tang Dynasty has also been found, the Saddharmapunṇḍarīka sutra or Lotus Sutra printed from 690 to 699.[2]

In Korea, an example of woodblock printing from the eighth century was discovered in 1966. A copy of the Buddhist Dharani Sutra called the Pure Light Dharani Sutra (Hangul: 무구정광대다라니경; Hanja: 無垢淨光大陀羅尼經; RR: Mugu jeonggwang dae darani-gyeong), discovered in Gyeongju, South Korea in a Silla dynasty pagoda that was repaired in 751 AD,[3] was undated but must have been created sometime before the reconstruction of the Shakyamuni Pagoda of Pulguk Temple, Kyongju Province in 751 AD.[4][5][6][7][8] The document is estimated to have been created no later than 704 AD.[3]

The printing process

The manuscript is transcribed onto thin slightly waxed sheets of paper by a professional calligrapher. The paper is placed face down on a block on which a thin layer of rice paste has been thinly spread and the back rubbed with a flat palm-fibre brush so that a clear impression of the inked area is left on the block. The engraving uses a set of sharp-edged tools to cut the characters with a double edged tool used to cut away any extra surfaces. The knife is held like a dagger in the right hand and guided by the middle finger of the left hand, drawing towards the cutter. The vertical lines are cut first, then the block is rotated 90 degrees and the horizontal lines cut.[9]

Four proof-readings are normally required - the transcript, the corrected transcript, first sample print from block and after any corrections have been made. A small correction to a block can be made by cutting a small notch and hammering in a wedge-shaped piece of wood. Larger errors require an inlay. After this the block is washed to remove any refuse.

To print, the block is fixed firmly on a table. The printer takes a round horsehair inking brush and applies ink with a vertical motion. The paper is then laid on the block and rubbed with a long narrow pad to transfer the impression to the paper. The paper is peeled off and set to dry. Because of the rubbing process, printing is only done on one side of the paper, and the paper is thinner than in the west, but two pages are normally printed at once.

Sample copies were sometimes made in red or blue, but black ink was always used for production. It is said that a skilled printer could produce as many as 1500 or 2000 double sheets in a day. Blocks can be stored and reused when extra copies are needed. 15,000 prints can be taken from a block with a further 10,000 after touching up.[10]

Spread of printing in Asia

Printing started in China in 593 AD.[11] Printing was promoted by the spread of Buddhism.

The Buddhist scroll known as the "Great Dharani Sutra of Immaculate and Pure Light" or "Spotless Pure Light Dharani Sutra" (Hangul: 무구정광대다라니경; Hanja: 無垢淨光大陀羅尼經; RR: Mugu jeonggwang dae darani-gyeong) is currently the oldest surviving woodblock print.[12][13] It was published in Korea before the year 751 A.D. during the Silla Kingdom.[4] This Darani Sutra was found inside the Seokga Pagoda of Bulguksa Temple in Gyeongju, Korea. Bulguksa Temple in Gyeongju in October 1966 within the seokgatap (释迦塔)while dismantling the tower to repair much of the sari was found with the prints. One row of the darani gyeongmun 8-9 are printed in the form of a roll. Tripitaka Koreana was printed between 1011 and 1082. It is the world's most comprehensive and oldest intact version of Buddhist canon. A reprint in 1237-51 used 81,258 blocks of magnolia wood, carved on both sides, which are still kept almost intact at Haeinsa. A printing office was established in the National Academy in 1101 and the Goryeo government collection numbered several tens of thousands.[14]

In Japan, one thousand copies of the Lotus sutra were printed in 1009 as a pious work, not intended to be read and therefore legibility was not so important. The spread of printing outside Buddhist circles didn't develop until the end of the 16th century.[15]

The westward movement of printing started from eastern Turkestan where printing in the Uyghur language appeared in about 1300, though the page numbers and descriptions are in Chinese. Both blocks and moveable type printing has been discovered at Turfan as well as several hundred wooden type for Uighur. After the Mongols conquered Turfan, a great number of Uighurs were recruited into the Mongol army and after the Mongols incorporated Persia in the middle of the 13th century, paper money was printed in Tabriz in 1294, following the Chinese system. The first description of the Chinese printing system was made by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani in 1301-11 in his history of the world.

Some fifty pieces of printed matter have been found in Egypt printed between 900 and 1300 in black ink on paper by the rubbing method in the Chinese style. Although there is no transmission evidence, experts believe there is a connection.[16]

According to the print scholar A. Hyatt Mayor, "it was the Chinese who really discovered the means of communication that was to dominate until our age."[17] Both woodblock and movable type printing were replaced in the second half of the 19th century by western-style printing, initially lithography.[18]

Movable type

Ceramic movable type in China

Bi Sheng (毕昇) (990–1051) developed the first known movable-type system for printing in China around 1040 AD during the Northern Song dynasty, using ceramic materials.[19][20] As described by the Chinese scholar Shen Kuo (沈括) (1031–1095):

- When he wished to print, he took an iron frame and set it on the iron plate. In this he placed the types, set close together. When the frame was full, the whole made one solid block of type. He then placed it near the fire to warm it. When the paste [at the back] was slightly melted, he took a smooth board and pressed it over the surface, so that the block of type became as even as a whetstone.

- For each character there were several types, and for certain common characters there were twenty or more types each, in order to be prepared for the repetition of characters on the same page. When the characters were not in use he had them arranged with paper labels, one label for each rhyme-group, and kept them in wooden cases.[19]

- If one were to print only two or three copies, this method would be neither simple nor easy. But for printing hundreds or thousands of copies, it was marvelously quick. As a rule he kept two forms going. While the impression was being made from the one form, the type was being put in place on the other. When the printing of the one form was finished, the other was then ready. In this way the two forms alternated and the printing was done with great rapidity.[19]

In 1193, Zhou Bida, an officer of Southern Song Dynasty, made a set of clay movable-type method according to the method described by Shen Kuo in his Dream Pool Essays, and printed his book Notes of The Jade Hall (《玉堂杂记》).[21]

The claim that Bi Sheng's clay types were fragile and "not practical for large-scale printing" and "short lived"[22] was refuted by facts and experiments. Bao Shicheng (1775–1885) wrote that baked clay moveable type was "as hard and tough as horn"; experiments show that clay type, after being baked in an oven, becomes hard and difficult to break, such that it remains intact after being dropped from a height of two metres onto a marble floor. The length of clay movable types in China was 1 to 2 centimetres, not 2mm, thus hard as horn. Clay type printing was practiced in China from the Song dynasty through the Qing dynasty, never "short lived".[23] As late as 1844 there were still books printed in China with ceramic movable types.[21]

Wooden movable type in China

Wooden movable type was also first developed around 1040 AD by Bi Sheng (990–1051), as described by the Chinese scholar Shen Kuo (1031–1095), but was abandoned in favour of clay movable types due to the presence of wood grains and the unevenness of the wooden type after being soaked in ink.[19][24]

In 1298, Wang Zhen (王祯/王禎), a Yuan dynasty governmental official of Jingde County, Anhui Province, China, re-invented a method of making movable wooden types. He made more than 30,000 wooden movable types and printed 100 copies of Records of Jingde County (《旌德县志》), a book of more than 60,000 Chinese characters. Soon afterwards, he summarized his invention in his book A method of making moveable wooden types for printing books. This system was later enhanced by pressing wooden blocks into sand and casting metal types from the depression in copper, bronze, iron or tin. This new method overcame many of the shortcomings of woodblock printing. Rather than manually carving an individual block to print a single page, movable type printing allowed for the quick assembly of a page of text. Furthermore, these new, more compact type fonts could be reused and stored.[19][20] The set of wafer-like metal stamp types could be assembled to form pages, inked, and page impressions taken from rubbings on cloth or paper.[20] In 1322,a Fenghua county officer Ma Chengde (马称德) in Zhejiang, made 100,000 wooded movable types and printed 43 volume Daxue Yanyi (《大学衍义》). Wooden movable types were used continually in China. Even as late as 1733, a 2300-volume Wuying Palace Collected Gems Edition (《武英殿聚珍版丛书》) was printed with 253500 wooden movable type on order of the Yongzheng Emperor, and completed in one year.

A number of books printed in Tangut script during the Western Xia (1038–1227) period are known, of which the Auspicious Tantra of All-Reaching Union that was discovered in the ruins of Baisigou Square Pagoda in 1991 is believed to have been printed sometime during the reign of Emperor Renzong of Western Xia (1139–1193).[25] It is considered by many Chinese experts to be the earliest extant example of a book printed using wooden movable type.[26]

A particular difficulty posed the logistical problems of handling the several thousand logographs whose command is required for full literacy in Chinese language. It was faster to carve one woodblock per page than to composit a page from so many different types. However, if one was to use movable type for multitudes of the same document, the speed of printing would be relatively quicker.[27]

Although the wooden type was more durable under the mechanical rigors of handling, repeated printing wore the character faces down, and the types could only be replaced by carving new pieces.

Metal movable type in China

Bronze movable type printing was invented in China no later than the 12th century, according to at least 13 material finds in China,[28] in large scale bronze plate printing of paper money and formal official documents issued by Jin (1115–1234) and Southern Song (1127–1279) dynasties with embedded bronze metal types for anti counterfeit markers. Such paper money printing might date back to the 11th-century jiaozi of Northern Song (960–1127).[29]

The typical example of this kind of bronze movable type embedded copper-block printing is a printed "check" of Jin Dynasty with two square holes for embedding two bronze movable type characters, each selected from 1000 different characters, such that each printed paper money has different combination of markers. A copper block printed paper money dated between 1215–1216 in the collection of Luo Zhenyu's Pictorial Paper Money of the Four Dynasties, 1914, shows two special characters one called Ziliao, the other called Zihao for the purpose of preventing counterfeit; over the Ziliao there is a small character (輶) printed with movable copper type, while over the Zihao there is an empty square hole, apparently the associated copper metal type was lost. Another sample of Song dynasty money of the same period in the collection of Shanghai Museum has two empty square holes above Ziliao as well as Zihou, due to lost of the two copper movable types. Song dynasty bronze block embedded with bronze metal movable type printed paper money was issued in large scale and in circulation for a long time.[30]

In the 1298 book Zao Huozi Yinshufa (《造活字印书法》/《造活字印書法》) of the early Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) official Wang Zhen, there is mention of tin movable type, used probably since the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), but this was largely experimental.[31] It was unsatisfactory due to its incompatibility with the inking process.[32]

During the Mongol Empire (1206–1405), printing using movable type spread from China to Central Asia. The Uyghurs of Central Asia used movable type, their script type adopted from the Mongol language, some with Chinese words printed between the pages, a strong evidence that the books were printed in China.[33]

During the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), Hua Sui in 1490 used bronze type in printing books.[34] In 1574 the massive 1000 volume encyclopedia Imperial Readings of the Taiping Era (《太平御览》/《太平御覧》) were printed with bronze movable type.

In 1725, the Qing Dynasty government made 250,000 bronze movable-type characters and printed 64 sets of the encyclopedic Gujin Tushu Jicheng (《古今图书集成》/《古今圖書集成》, Complete Collection of Illustrations and Writings from the Earliest to Current Times). Each set consisted of 5040 volumes, making a total of 322,560 volumes printed using movable type.[33]

Metal movable type in Korea

The transition from wood type to movable metal type occurred in Korea during the Goryeo Dynasty, some time in the 13th century, to meet the heavy demand for both religious and secular books. A set of ritual books, Sangjeong Gogeum Yemun were printed with movable metal type in 1234.[35] The credit for the first metal movable type may go to Choe Yun-ui of the Goryeo Dynasty in 1234.[36]

The techniques for bronze casting, used at the time for making coins (as well as bells and statues) were adapted to making metal type. Unlike the metal punch system thought to be used by Gutenberg, the Koreans used a sand-casting method. The following description of the Korean font casting process was recorded by the Joseon dynasty scholar Song Hyon (15th century):

- At first, one cuts letters in beech wood. One fills a trough level with fine sandy [clay] of the reed-growing seashore. Wood-cut letters are pressed into the sand, then the impressions become negative and form letters [molds]. At this step, placing one trough together with another, one pours the molten bronze down into an opening. The fluid flows in, filling these negative molds, one by one becoming type. Lastly, one scrapes and files off the irregularities, and piles them up to be arranged.[37]

While metal movable type printing was developed in Korea and the oldest extant metal print book had been printed in Korea,[38] Korea never witnessed a printing revolution comparable to Europe's:

- Korean printing with movable metallic type developed mainly within the royal foundry of the Yi dynasty. Royalty kept a monopoly of this new technique and by royal mandate suppressed all non-official printing activities and any budding attempts at commercialization of printing. Thus, printing in early Korea served only the small, noble groups of the highly stratified society.[39]

A potential solution to the linguistic and cultural bottleneck that held back movable type in Korea for two hundred years appeared in the early 15th century—a generation before Gutenberg would begin working on his own movable type invention in Europe—when King Sejong devised a simplified alphabet of 24 characters called Hangul for use by the common people, which could have made the typecasting and compositing process more feasible.

Movable type in Japan

Though the Jesuits operated a Western movable type printing-press in Nagasaki, Japan, printing equipment[40] brought back by Toyotomi Hideyoshi's army in 1593 from Korea had far greater influence on the development of the medium. Four years later, Tokugawa Ieyasu, even before becoming shogun, effected the creation of the first native movable type,[40] using wooden type-pieces rather than metal. He oversaw the creation of 100,000 type-pieces, which were used to print a number of political and historical texts.

An edition of the Confucian Analects was printed in 1598 using metal moveable type printing equipment at the order of Emperor Go-Yōzei. This document is the oldest work of Japanese moveable type printing extant today. Despite the appeal of moveable type, however, it was soon decided that the running script style of Japanese writings would be better reproduced using woodblocks, and so woodblocks were once more adopted; by 1640 they were once again being used for nearly all purposes.[41]

Comparison of Woodblock and Movable type in East Asia

Despite the introduction of movable type from the 11th century, printing using woodblocks remained dominant in East Asia until the introduction of lithography and photolithography in the 19th century. To understand this it is necessary to consider both the nature of the language and the economics of printing.

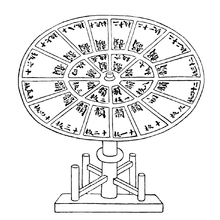

Given that the Chinese language does not use an alphabet it was usually necessary for a set of type to contain 100,000 or more blocks, which was a substantial investment. Common characters need 20 or more copies, and rarer characters only a single copy. In the case of wood, the characters were either produced in a large block and cut up, or the blocks were cut first and the characters cut afterwards. In either case the size and height of the type had to be carefully controlled to produce pleasing results. To handle the typesetting, Wang Zhen used revolving tables about 2m in diameter in which the characters were divided according to the five tones and the rhyme sections according to the official book of rhymes. The characters were all numbered and one man holding the list called out the number to another who would fetch the type.

This system worked well when the run was large. Wang Zhen's initial project to produce 100 copies of a 60,000 character gazetteer of the local district was produced in less than a month. But for the smaller runs typical of the time it was not such an improvement. A reprint required resetting and re-proofreading, unlike the wooden block system where it was feasible to store the blocks and reuse them. Individual wooden characters didn't last as long as complete blocks. When metal type was introduced it was harder to produce aesthetically pleasing type by the direct carving method.

It is unknown whether metal movable types used from the late 15th century in China were cast from moulds or carved individually. Even if they were cast, there were not the economies of scale available with the small number of different characters used in an alphabetic system. The wage for engraving on bronze was many times that for carving characters on wood and a set of metal type might contain 200-400,000 characters. Additionally, the ink traditionally used in Chinese printing, typically composed of pine soot bound with glue, didn't work well with the tin originally used for type.

As a result of all this, movable type was initially used by government offices which needed to produce large number of copies and by itinerant printers producing family registers who would carry perhaps 20,000 pieces of wooden type with them and cut any other characters needed locally. But small local printers often found that wooden blocks suited their needs better.[10]

Mechanical presses

Mechanical presses as used in European printing remained unknown in East Asia.[42] Instead, printing remained an unmechanized, laborious process with pressing the back of the paper onto the inked block by manual "rubbing" with a hand tool.[43] In Korea, the first printing presses were introduced as late as 1881-83,[44][45] while in Japan, after an early but brief interlude in the 1590s,[46] Gutenberg's printing press arrived in Nagasaki in 1848 on a Dutch ship.[47]

Contrary to Gutenberg printing, which allowed printing on both sides of the paper from its very beginnings (although not simultaneously until very recent times), East Asian printing was done only on one side of the paper, because the need to rub the back of the paper when printing would have spoilt the first side when the second side was printed.[43] Another reason was that, unlike in Europe where Gutenberg introduced more suitable oil-based ink, Asian printing remained confined to water-based inks which tended to soak through the paper.

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Fifty Wonders of Korea: Volume 1. Seoul: Samjung Munhwasa, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9797263-1-6.

- 1 2 3 Pan, Jixing. "On the Origin of Printing in the Light of New Archaeological Discoveries," in Chinese Science Bulletin, 1997, Vol. 42, No. 12: 976–981. ISSN 1001-6538. Pages 979–980.

- 1 2 Tsien 1985, pp. 149,150

- 1 2 Pratt, Keith (August 15, 2007). Everlasting Flower: A History of Korea. Reaktion Books. p. 74. ISBN 978-1861893352.

- ↑ Early Printing in Korea. Korea Cultural Center

- ↑ Gutenberg and the Koreans: Asian Woodblock Books. Rightreading.com

- ↑ Gutenberg and the Koreans: Cast-Type Printing in Korea's Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392). Rightreading.com

- ↑ North Korea - Silla. Country Studies

- ↑ Tsien 1985, pp. 197–200

- 1 2 Tsien 1985, p. 201

- ↑ "Great Chinese Inventions". Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- ↑ "Spotless Pure Light Dharani Sutra". National Museum of Korea. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ↑ "Seokguram Grotto and Bulguksa Temple". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ↑ Tsien 1985, pp. 323–5

- ↑ Tsien 1985, pp. 338–41

- ↑ Carter, 1955, pp 179-80

- ↑ A Hyatt Mayor, Prints and People, Metropolitan Museum of Art/Princeton, 1971, nos 1-4. ISBN 0-691-00326-2

- ↑ "The phase of technological development that distinguished China's and particularly Shanghai's early Westernized printing industry was that involving lithography." Christopher A. Reed (2004). Gutenberg in Shanghai: Chinese Print Capitalism, 1876-1937. Canada, UBC Press. p. 89.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tsien 1985

- 1 2 3 Man, John. The Gutenberg Revolution: The story of a genius that changed the world (c) 2002 Headline Book Publishing, a division of Hodder Headline, London. ISBN 0-7472-4504-5. A detailed examination of Gutenberg's life and invention, interwoven with the underlying social and religious upheaval of Medieval Europe on the eve of the Renaissance.

- 1 2 Xu Yinong, Moveable Type Books (徐忆农《活字本》) ISBN 7-80643-795-9

- ↑ Sohn, Pow-Key, "Early Korean Printing," Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 79, No. 2 (April -June , 1959), pp. 96-103 (100).

- ↑ Pan Jixing, A history of movable metal type printing technique in China 2001, p22

- ↑ Shen Kuo. Dream Pool Essays.

- ↑ Zhang Yuzhen (张玉珍) (2003). "世界上现存最早的木活字印本—宁夏贺兰山方塔出土西夏文佛经《吉祥遍至口和本续》介绍" [The world's oldest extant book printed with wooden movable type]. Library and Information (《图书与情报》) (1). ISSN 1003-6938.

- ↑ Hou Jianmei (侯健美); Tong Shuquan (童曙泉) (20 December 2004). "《大夏寻踪》今展国博" ['In the Footsteps of the Great Xia' now exhibiting at the National Museum]. Beijing Daily (《北京日报》).

- ↑ Tsien 1985, p. 201

- ↑ 韩国剽窃活字印刷发明权只是第一步

- ↑ Pan Jixing, A history of movable metal type printing technique in China 2001, pp. 41-54

- ↑ A History of Moveable Type Printing in China, by Pan Jixing, Professor of the Institute for History of Science, Academy of Science, Beijing, China, English Abstract, p273

- ↑ Wang Zhen (1298). Zao Huozi Yinshufa (《造活字印書法》).

近世又铸锡作字, 以铁条贯之 (rendering: In the modern times, there's melten Tin Movable type, and linked them with iron bar)

- ↑ Tsien 1985, p. 217

- 1 2 Chinese Paper and Printing, A Cultural History, by Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin

- ↑ Tsien 1985, p. 212

- ↑ Thomas Christensen (2006). "Did East Asian Printing Traditions Influence the European Renaissance?". Arts of Asia Magazine (to appear). Retrieved 2006-10-18.

- ↑ Baek Sauk Gi (1987). Woong-Jin-Wee-In-Jun-Gi #11 Jang Young Sil, p. 61. Woongjin Publishing.

- ↑ Sohn, Pow-Key (Summer 1993). "Printing Since the 8th Century in Korea". Koreana. 7 (2): 4–9.

- ↑ Michael Twyman, The British Library Guide to Printing: History and Techniques, London: The British Library, 1998 available online.

- ↑ Sohn, Pow-Key, "Early Korean Printing," Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 79, No. 2 (April -June , 1959), pp. 96-103 (103).

- 1 2 Lane, Richard (1978). "Images of the Floating World." Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky. P. 33.

- ↑ Sansom, George (1961). "A History of Japan: 1334-1615." Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

- ↑ printing. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved November 5, 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica 2006 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD.

- 1 2 An Introduction to a History of Woodcut, Arthur M. Hind, p. 64-127 , Houghton Mifflin Co. 1935 (in USA), reprinted Dover Publications, 1963. ISBN 0-486-20952-0

- ↑ Albert A. Altman, "Korea's First Newspaper: The Japanese Chosen shinpo", The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 43, No. 4. (August 1984), pp. 685-696.

- ↑ Melvin McGovern, "Early Western Presses in Korea", Korea Journal, 1967, pp. 21-23.

- ↑ Akihiro Kinoshita, Keiichi Ishikawa, "Early Printing History in Japan", Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, Volume 73.1998 (1998), pp. 30-35 (34).

- ↑ Akihiro Kinoshita, Keiichi Ishikawa, "Early Printing History in Japan", Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, Volume 73.1998 (1998), pp. 30-35 (33 et seq.).

Sources

- Carter, Thomas Frances. The Invention of Printing in China, and its spread Westward" 2nd ed., revised by L. Carrington Goodrich. NY:Ronald Press, 1955. (1st ed, 1925)

- Fifty Wonders of Korea: Volume 1. Seoul: Samjung Munhwasa, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9797263-1-6.

- Lane, Richard. (1978). Images from the Floating World, The Japanese Print. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192114471; OCLC 5246796

- Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (1985). Paper and Printing. Needham, Joseph Science and Civilization in China. vol. 5 part 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 201–217. ISBN 0-521-08690-6.; also published in Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd., 1986.

- Twitchett, Denis. Printing and Publishing in Medieval China., New York, Frederick C. Beil, 1983.