History of the Maya civilization

|

| Maya civilization |

|---|

| History |

| Preclassic Maya |

| Classic Maya collapse |

| Spanish conquest of the Maya |

The history of Maya civilization is divided into three principal periods: the Preclassic, Classic and Postclassic periods;[1] these were preceded by the Archaic Period, which saw the first settled villages and early developments in agriculture.[2] Modern scholars regard these periods as arbitrary divisions of chronology of the Maya civilization, rather than indicative of cultural evolution or decadence.[3] Definitions of the start and end dates of period spans can vary by as much as a century, depending on the author.[4] The Preclassic lasted from approximately 2000 BC to approximately 250 AD; this was followed by the Classic, from 250 AD to roughly 950 AD, then by the Postclassic, from 950 AD to the middle of the 16th century.[5] Each period is further subdivided:

| Period | Division | Dates | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Archaic | 8000–2000 BC[6] | ||

| Preclassic | Early Preclassic | 2000–1000 BC | |

| Middle Preclassic | Early Middle Preclassic | 1000–600 BC | |

| Late Middle Preclassic | 600–350 BC | ||

| Late Preclassic | Early Late Preclassic | 350–1 BC | |

| Late Late Preclassic | 1 BC – AD 159 | ||

| Terminal Preclassic | AD 159–250 | ||

| Classic | Early Classic | AD 250–550 | |

| Late Classic | AD 550–830 | ||

| Terminal Classic | AD 830–950 | ||

| Postclassic | Early Postclassic | AD 950–1200 | |

| Late Postclassic | AD 1200–1539 | ||

| Contact period | AD 1511–1697[7] | ||

Preclassic period (c. 2000 BC – 250 AD)

The Maya developed their first civilization in the Preclassic period.[9] Scholars continue to discuss when this era of Maya civilization began. Discoveries of Maya occupation at Cuello, Belize have been carbon dated to around 2600 BC.[10] Settlements were established around 1800 BC in the Soconusco region of the Pacific coast, and they were already cultivating the staple crops of the Maya diet, including maize, beans, squash, and chili pepper.[11] This period, known as the Early Preclassic,[11] was characterized by sedentary communities and the introduction of pottery and fired clay figurines.[12]

During the Middle Preclassic Period, small villages began to grow to form cities.[13] By 500 BC these cities possessed large temple structures decorated with stucco masks representing gods.[14] Nakbe in the Petén Department of Guatemala is the earliest well-documented city in the Maya lowlands,[15] where large structures have been dated to around 750 BC.[13] Nakbe already featured the monumental masonry architecture, sculpted monuments and causeways that characterised later cities in the Maya lowlands.[15] The northern lowlands of Yucatán were widely settled by the Middle Preclassic.[16] By approximately 400 BC, near the end of the Middle Preclassic period, early Maya rulers were raising stelae that celebrated their achievements and validated their right to rule.[17]

Murals excavated in 2005 have pushed back the origin of Maya writing by several centuries, with a developed script already being used at San Bartolo in Petén by the 3rd century BC, and it is now evident that the Maya participated in the wider development of Mesoamerican writing in the Preclassic.[18] In the Late Preclassic Period, the enormous city of El Mirador grew to cover approximately 16 square kilometres (6.2 sq mi).[19] It possessed paved avenues, massive triadic pyramid complexes dated to around 150 BC, and stelae and altars that were erected in its plazas.[19] El Mirador is considered to be one of the first capital cities of the Maya civilization.[19] The swamps of the Mirador Basin appear to have been the primary attraction for the first inhabitants of the area as evidenced by the unusual cluster of large cities around them.[20] The city of Tikal, later to be one of the most important of the Classic Period Maya cities, was already a significant city by around 350 BC, although it did not match El Mirador.[21] The Late Preclassic cultural florescence collapsed in the 1st century AD and many of the great Maya cities of the epoch were abandoned; the cause of this collapse is as yet unknown.[14]

In the highlands, Kaminaljuyu emerged as a principal centre in the Late Preclassic, linking the Pacific coastal trade routes with the Motagua River route, as well as demonstrating increased contact with other sites along the Pacific coast.[22] Kaminaljuyu was situated at a crossroads and controlled the trade routes westwards to the Gulf coast, north into the highlands, and along the Pacific coastal plain to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and El Salvador. This gave it control over the distribution networks for important goods such as jade, obsidian and cinnabar.[23] Within this extended trade route, Takalik Abaj and Kaminaljuyu appear to have been the two principal foci.[24] The early Maya style of sculpture spread throughout this network.[25] Takalik Abaj and Chocolá were two of the most important cities on the Pacific coastal plain during the Late Preclassic,[26] and Komchen grew to become an important site in northern Yucatán during the Preclassic.[27]

Classic period (c. 250–900 AD)

The Classic period is largely defined as the period during which the lowland Maya raised dated monuments using the Long Count calendar.[28] This period marked the peak of large-scale construction and urbanism, the recording of monumental inscriptions, and demonstrated significant intellectual and artistic development, particularly in the southern lowland regions.[28] The Classic period Maya political landscape has been likened to that of Renaissance Italy or Classical Greece, with multiple city-states engaged in a complex network of alliances and enmities.[29]

During the Classic Period, the Maya civilization achieved its greatest florescence.[14] The Maya developed an agriculturally intensive, city-centred civilization consisting of numerous independent city-states – some subservient to others.[31] During the Early Classic, cities throughout the Maya region were influenced by the great metropolis of Teotihuacan in the distant Valley of Mexico.[32] In AD 378, Teotihuacan decisively intervened at Tikal and other nearby cities, deposed its ruler and installed a new Teotihuacan-backed dynasty.[33] This intervention was led by Siyaj K'ak' ("Born of Fire"), who arrived at Tikal on 8.17.1.4.12 (c. 31 January 378). The king of Tikal, Chak Tok Ich'aak I, died on the same day, suggesting a violent takeover.[34] A year later, Siyaj K'ak' oversaw the installation of a new king, Yax Nuun Ayiin I.[35] The new king's father was Spearthrower Owl, who possessed a central Mexican name, and may have been the king of either Teotihuacan, or Kaminaljuyu.[36] The installation of the new dynasty led to a period of political dominance when Tikal became the most powerful city in the central lowlands.[35]

At its height during the Late Classic, the Tikal city polity had expanded to have a population of well over 100,000.[37] Tikal's great rival was Calakmul, another powerful city polity in the Petén Basin.[38] Tikal and Calakmul both developed extensive systems of allies and vassals; lesser cities that entered one of these networks gained prestige from their association with the top-tier city, and maintained peaceful relations with other members of the same network.[39] Tikal and Calakmul engaged in the manoeuvering of their alliance networks against each other; at various points during the Classic period, one or other of these powers would gain a strategic victory over its great rival, resulting in respective periods of florescence and decline.[40]

In 629, B'alaj Chan K'awiil, a son of the Tikal king K'inich Muwaan Jol II, was sent to found a new city 120 kilometres (75 mi) to the west, at Dos Pilas, in the Petexbatún region, apparently as an outpost to extend Tikal's power beyond the reach of Calakmul. The young prince was just four years old at the time.[41] With the establishment of the new kingdom, Dos Pilas advertised its origin by adopting the emblem glyph of Tikal as its own.[42] For the next two decades he fought loyally for his brother and overlord at Tikal. In AD 648, king Yuknoom Ch'een II ("Yuknoom the Great") of Calakmul attacked and defeated Dos Pilas, capturing Balaj Chan K’awiil. At about the same time, the king of Tikal was killed. Yuknoom Che'en II then reinstated Balaj Chan K'awiil upon the throne of Dos Pilas as his vassal.[43] In an extraordinary act of treachery for someone claiming to be of the Tikal royal family, he thereafter served as a loyal ally of Calakmul, Tikal's sworn enemy.[44]

In the southeast, Copán was the most important city.[38] Its Classic-period dynasty was founded in 426 by K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo'. The new king had strong ties with central Petén and Teotihuacan, and it is likely that he was originally from Tikal.[45] Copán reached the height of its cultural and artistic development during the rule of Uaxaclajuun Ub'aah K'awiil, who reigned from 695 to 738.[46] His reign ended catastrophically in April 738, when he was captured by his vassal, king K'ak' Tiliw Chan Yopaat of Quiriguá.[47] The captured lord of Copán was taken back to Quiriguá and, in early May 738, he was decapitated in a public ritual.[48] It is likely that this coup was backed by Calakmul, in order to weaken a powerful ally of Tikal.[49] Palenque and Yaxchilan were the most powerful cities in the Usumacinta region.[38] In the highlands, Kaminaljuyu in the Valley of Guatemala was already a sprawling city by AD 300.[50] In the north of the Maya area, Coba was the most important capital.[51]

Capital cities of Maya kingdoms could vary considerably in size, apparently related to how many vassal cities were tied to the capital.[52] Overlords of city-states that held sway over a greater number of subordinate lords could command greater quantities of tribute in the form of goods and labour.[53] The most notable forms of tribute pictured on Maya ceramics are cacao, textiles and feathers.[53] The social basis of the Classic Maya civilization was an extended political and economic network that reached throughout the Maya area and beyond into the greater Mesoamerican region.[54] The dominant Classic period polities were located in the central lowlands; during this period the southern highlands and northern lowlands can be considered culturally, economically, and politically peripheral to this core area. Those loci that existed between the core and the periphery acted as centres of trade and commerce.[55]

The most notable monuments are the pyramid-temples and palaces they built in the centres of their greatest cities.[56] At this time, the use of hieroglyphic script on monuments became widespread, and left a large body of information including dated dynastic records, alliances, and other interactions between Maya polities.[57] The sculpting of stone stelae spread throughout the Maya area during the Classic period,[58] and pairings of sculpted stelae and low circular altars are considered a hallmark of Classic Maya civilization.[59] During the Classic period almost every Maya kingdom in the southern lowlands raised stelae in its ceremonial centre.[60] The epigrapher David Stuart first proposed that the Maya regarded their stelae as te tun, "stone trees", although he later revised his reading to lakamtun, meaning "banner stone".[61] According to Stuart this may refer to the stelae as stone versions of vertical standards that once stood in prominent places in Maya city centres, as depicted in ancient Maya graffiti.[62] The core purpose of a stela was to glorify the king.[63]

The Maya civilization participated in long-distance trade, and important trade routes ran from the Motagua River to the Caribbean Sea, then north up the coast to Yucatán. Another route ran from Verapaz along the Pasión River to the trading port at Cancuen; from there trade routes ran east to Belize, northwards to central and northern Petén, and onwards to the Gulf of Mexico and the west coast of the Yucatán Peninsula.[64] Important elite-status trade goods included jade, fine ceramics, and quetzal feathers.[65] More basic trade goods may have included obsidian, salt and cacao.[66]

Classic Maya collapse

During the 9th century AD, the central Maya region suffered major political collapse, marked by the abandonment of cities, the ending of dynasties and a northward shift in activity.[32] This decline was coupled with a cessation of monumental inscriptions and large-scale architectural construction. No universally accepted theory explains this collapse, but it is likely to have resulted from a combination of causes, including endemic internecine warfare, overpopulation resulting in severe environmental degradation, and drought.[67] During this period, known as the Terminal Classic, the northern cities of Chichen Itza and Uxmal show increased activity.[32] Major cities in the northern Yucatán Peninsula continued to be inhabited long after the cities of the southern lowlands ceased to raise monuments.[68]

There is evidence that the Maya population exceeded the carrying capacity of the environment, resulting in depleted agricultural resources, deforestation, and overhunting of megafauna. A 200-year long drought appears to have occurred around the same time.[69] Classic Maya social organisation was based upon the ritual authority of the ruler, rather than central control of trade and food distribution. This model of rulership was poorly structured to respond to changes, with the ruler's freedom of action being limited to traditional responses. The rulers reacted in their culturally-bound manner, by intensifying such activities as construction, ritual, and warfare. This was counterproductive and only served to exacerbate systemic problems.[70]

By the 9th and 10th centuries, this resulted in collapse of the system of rulership based around the divine power of the ruling lord. In the northern Yucatán, individual rule was replaced by a ruling council formed from elite lineages. In the southern Yucatán and central Petén, kingdoms generally declined; in western Petén and some other areas, the changes were catastrophic and resulted in the rapid depopulation of cities.[71] Within a couple of generations, large swathes of the central Maya area were all but abandoned.[72] Relatively rapid collapse affected portions of the southern Maya area that included the southern Yucatán Peninsula, northern Chiapas and Guatemala, and the area around Copán in Honduras. The largest cities had populations numbering 50,000 to 120,000 and were linked to networks of subsidiary sites. Both the capitals and their secondary centres were generally abandoned within a period of 50 to 100 years.[73]

By the late 8th century, endemic warfare had engulfed the Petexbatún region of Petén, resulting in the abandonment of Dos Pilas and Aguateca.[74] One by one, many once-great cities stopped sculpting dated monuments and were abandoned; the last monuments at Palenque, Piedras Negras and Yaxchilan were dated to between 795 and 810, over the following decades, Calakmul, Naranjo, Copán, Caracol and Tikal all fell into obscurity. The last Long Count date was inscribed at Toniná in 909. Stelae were no longer raised, and squatters moved into abandoned royal palaces. Mesoamerican trade routes shifted and bypassed Petén.[75]

Postclassic period (c. 950–1539 AD)

The great cities that dominated Petén had fallen into ruin by the beginning of the 10th century AD with the onset of the Classic Maya collapse.[77] Although much reduced, a significant Maya presence remained into the Postclassic period after the abandonment of the major Classic period cities; the population was particularly concentrated near permanent water sources.[78] Unlike during previous cycles of contraction in the Maya region, abandoned lands were not quickly resettled in the Postclassic.[73] Activity shifted to the northern lowlands and the Maya Highlands; this may have involved migration from the southern lowlands, since many Postclassic Maya groups had migration myths.[79] Chichen Itza rose to prominence in the north in the 8th century AD, coincident with the abandonments occurring in the south, which underlines the economic and political factors involved in the collapse.[73] Chichen Itza became what was probably the largest, most powerful and most cosmopolitan of all Maya cities.[80] Chichen Itza and its Puuc neighbours declined dramatically in the 11th century, and this may represent the final episode of the Classic period collapse. After the decline of Chichen Itza, the Maya region lacked a dominant power until the rise of the city of Mayapan in the 12th century. New cities arose near the Caribbean and Gulf coasts, and new trade networks were formed.[81]

The Postclassic Period was marked by a series of changes that distinguished its cities from those of the preceding Classic Period.[82] The once-great city of Kaminaljuyu in the Valley of Guatemala was abandoned after a period of continuous occupation that spanned almost two thousand years.[83] This was symptomatic of changes that were sweeping across the highlands and neighbouring Pacific coast, with long-occupied cities in exposed locations relocated, apparently due to a proliferation of warfare. Cities came to occupy more-easily defended hilltop locations surrounded by deep ravines, with ditch-and-wall defences sometimes supplementing the protection provided by the natural terrain.[83] Walled defences have been identified at a number of sites in the north, including Chacchob, Chichen Itza, Cuca, Ek Balam, Mayapan, Muna, Tulum, Uxmal, and Yaxuna.[84] One of the most important cities in the Guatemalan Highlands at this time was Q'umarkaj, also known as Utatlán, the capital of the aggressive K'iche' Maya kingdom.[82] The government of Maya states, from the Yucatán to the Guatemalan highlands, was often organised as joint rule by a council. However, in practice one member of the council could act as a supreme ruler, with the other members serving him as advisors.[85]

Mayapan was abandoned around 1448, after a period of political, social and environmental turbulence that in many ways echoes the Classic period collapse in the southern Maya region. The abandonment of the city was followed by a period of prolonged warfare in the Yucatán Peninsula, which only ended shortly before Spanish contact in 1511. Even without a dominant regional capital, the early Spanish explorers reported wealthy coastal cities and thriving marketplaces.[81]

During the Late Postclassic, the Yucatán Peninsula was divided into a number of independent provinces that shared a common culture but varied in their internal sociopolitical organisation.[86] Two of the most important provinces were Mani and Sotuta, which were mutually hostile.[87] At the time of Spanish contact, polities in the northern Yucatán peninsula included Mani, Cehpech, Chakan, Ah Kin Chel, Cupul, Chikinchel. Ecab, Uaymil, Chetumal, Cochuah, Tases, Hocaba, Sotuta, Chanputun (modern Champotón), and Acalan.[88] A number of polities and groups inhabited the southern portion of the peninsula incorporating the Petén Basin, Belize, and surrounding areas,[89] including the Kejache, the Itza,[90] the Kowoj,[91] the Yalain,[92] the Chinamita, and the Icaiche, the Manche Ch'ol, and the Mopan.[93] The Cholan Maya-speaking Lakandon (not to be confused with the modern inhabitants of Chiapas by that name) controlled territory along the tributaries of the Usumacinta River spanning eastern Chiapas and southwestern Petén.[90]

On the eve of the Spanish conquest, the highlands of Guatemala were dominated by several powerful Maya states.[94] In the centuries preceding the arrival of the Spanish, the K'iche' had carved out a small empire covering a large part of the western Guatemalan Highlands and the neighbouring Pacific coastal plain. However, in the late 15th century the Kaqchikel rebelled against their former K'iche' allies and founded a new kingdom to the southeast, with Iximche as its capital. In the decades before the Spanish invasion the Kaqchikel kingdom had been steadily eroding the kingdom of the K'iche'.[95] Other highland groups included the Tz'utujil around Lake Atitlán, the Mam in the western highlands and the Poqomam in the eastern highlands.[96] The central highlands of Chiapas were occupied by a number of Maya peoples,[97] including the Tzotzil, who were divided into a number of provinces,[98] and the Tojolabal.[99]

Contact period and Spanish conquest (1511–1697 AD)

In 1511, a Spanish caravel was wrecked in the Caribbean, and about a dozen survivors made landfall on the coast of Yucatán. They were seized by a Maya lord, and most were sacrificed, although two managed to escape. From 1517 to 1519, three separate Spanish expeditions explored the Yucatán coast, and engaged in a number of battles with the Maya inhabitants.[100] After the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan fell to the Spanish in 1521, Hernán Cortés despatched Pedro de Alvarado to Guatemala with 180 cavalry, 300 infantry, 4 cannons, and thousands of allied warriors from central Mexico;[101] they arrived in Soconusco in 1523.[102] The K'iche' capital, Q'umarkaj, fell to Alvarado in 1524.[103] Shortly afterwards, the Spanish were invited as allies into Iximche, the capital city of the Kaqchikel Maya.[104] Good relations did not last, due to excessive Spanish demands for gold as tribute, and the city was abandoned a few months later.[105] This was followed by the fall of Zaculeu, the Mam Maya capital, in 1525.[106] Francisco de Montejo and his son, Francisco de Montejo the Younger, launched a lengthy series of campaigns against the polities of the Yucatán Peninsula in 1527, and finally completed the conquest of the northern portion of the peninsula in 1546.[107] This left only the Maya kingdoms of the Petén Basin independent.[108] In 1697, Martín de Ursúa launched an assault upon the Itza capital Nojpetén and the last remaining independent Maya city fell to the Spanish.[109]

Persistence of Maya culture

The Spanish conquest stripped away most of the defining features of Maya civilization. However, many Maya villages remained remote from Spanish colonial authority, and for the most part continued to manage their own affairs. Maya communities and the nuclear family maintained their traditional day-to-day life.[110] The basic Mesoamerican diet of maize and beans continued, although agricultural output was improved by the introduction of steel tools. Traditional crafts such as weaving, ceramics, and basketry continued to be produced. Community markets and trade in local products continued long after the conquest. At times the colonial administration encouraged the traditional economy in order to extract tribute in the form of ceramics or cotton textiles, although these were usually made to European specifications. Maya beliefs and language proved resistant to change, in spite of the vigorous efforts of Catholic missionaries.[111] The 260-day tzolk'in ritual calendar continues in use in modern Maya communities in the highlands of Guatemala and Chiapas,[112] and millions of Mayan-language speakers inhabit the territory in which their ancestors developed their civilization.[113]

Investigation of the Maya civilization

From the 16th century onwards, Spanish soldiers, clergy and administrators were familiar with pre-Columbian Maya history and beliefs. The agents of the Catholic Church wrote detailed accounts of the Maya, in support of their efforts at evangelisation, and absorption of the Maya into the Spanish Empire.[114] The writings of 16th-century Bishop Diego de Landa, who had infamously burned a large number of Maya books, contain many details of Maya culture, including their beliefs and religious practices, calendar, aspects of their hieroglyphic writing, and oral history.[115] This was followed by various Spanish priests and colonial officials who left descriptions of ruins they visited in Yucatán and Central America. These early visitors were well aware of the association between the ruins and the Maya inhabitants of the region.[116]

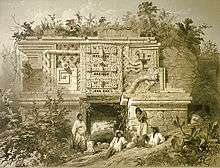

In 1839 American traveller and writer John Lloyd Stephens, familiar with earlier Spanish investigations, set out to visit Uxmal, Copán, Palenque, and other sites with English architect and draftsman Frederick Catherwood.[117] Their illustrated accounts of the ruins sparked strong popular interest in the region and the people, and brought the Maya to the attention of the world.[114] Their account was picked up by 19th century antiquarians such as Augustus Le Plongeon and Désiré Charnay, who attributed the ruins to Old World civilizations, or sunken continents.[118] The later 19th century saw the recording and recovery of ethnohistoric accounts of the Maya, and the first steps in deciphering Maya hieroglyphs.[119]

The final two decades of the 19th century saw the birth of modern scientific archaeology in the Maya region, with the meticulous work of Alfred Maudslay and Teoberto Maler.[120] Sites such as Altar de Sacrificios, Coba, Seibal, and Tikal were cleared and documented.[121] By the early 20th century, the Peabody Museum was sponsoring excavations at Copán and in the Yucatán Peninsula,[121] and artefacts were being smuggled out of the region to the museum's collection. In the first two decades of the 20th century, advances were made in the deciphering of the Maya calendar, and identification of deities, dates, and religious concepts.[122] Sylvanus Morley began a project to document every known Maya monument and hieroglyphic inscription, in some cases recording the texts of monuments that have since been destroyed.[123] The Carnegie Institution sponsored excavations at Copán, Chichen Itza and Uaxactun, and the modern foundations of Maya studies were laid.[124] From the 1930s onwards, the pace of archaeological exploration increased dramatically, with large-scale excavations across the entire Maya region.[125]

However, in many locations, Maya ruins have been overgrown by the jungle, becoming dense enough to hide structures just a few meters away. To find unidentified ruins, researchers have turned to satellite imagery, in order to look at the visible and near-infrared spectra. Due to their limestone construction, the monuments affected the chemical makeup of the soil as they deteriorated; some moisture-loving plants are entirely absent, while others were killed off or discoloured.[126]

In the 1960s, the distinguished Mayanist J. Eric S. Thompson promoted the ideas that Maya cities were essentially vacant ceremonial centres serving a dispersed population in the forest, and that the Maya civilization was governed by peaceful astronomer-priests.[127] These ideas arose from the limited understanding of Maya script at the time;[127] they began to collapse with major advances in the decipherment of the script in the late 20th century, pioneered by Heinrich Berlin, Tatiana Proskouriakoff, and Yuri Knorozov.[128] As breakthroughs in the understanding of Maya script were made from the 1950s onwards, the texts revealed the warlike activities of the Classic Maya kings, and the view of the Maya as peaceful could no longer be supported.[129] Detailed settlement surveys of Maya cities revealed the evidence of large populations, putting an end to the vacant ceremonial centre model.[130]

Notes

- ↑ Estrada-Belli 2011, pp. 1, 3.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 98. Estrada-Belli 2011, p. 38.

- ↑ Estrada-Belli 2011, p. 1.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, p. 17.

- 1 2 Estrada-Belli 2011, p. 3.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 98.

- ↑ Masson 2012, p. 18238. Pugh and Cecil 2012, p. 315.

- ↑ Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2010, p. 1.

- ↑ Estrada-Belli 2011, p. 28.

- ↑ Hammond et al. 1976, pp. 579–581.

- 1 2 Drew 1999, p.6.

- ↑ Coe 1999, p. 47.

- 1 2 Olmedo Vera 1997, p.26.

- 1 2 3 Martin and Grube 2000, p.8.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 276.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, pp. 182, 197.

- ↑ Saturno, Stuart and Beltrán 2006, pp. 1281–1283.

- 1 2 3 Olmedo Vera 1997, p.28.

- ↑ Hansen et al. 2006, p.740.

- ↑ Martin and Grube 2000, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Love 2007, pp. 293, 297. Popenoe de Hatch and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, p. 991.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 232.

- ↑ Popenoe de Hatch and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, p. 991.

- ↑ Orrego Corzo and Schieber de Lavarreda 2001, p. 788.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 236.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 275.

- 1 2 Coe 1999, p. 81.

- ↑ Martin and Grube 2000, p. 21.

- ↑ Schele and Mathews 1999, pp. 179, 182–183.

- ↑ Acemoglu and Robinson 2012, pp. 143–149.

- 1 2 3 Martin and Grube 2000, p.9.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, p. 218. Estrada-Belli 2011, pp. 123–126.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 322. Martin and Grube 2000, p. 29.

- ↑ Martin and Grube 2000, p. 30. Sharer and Traxler 2006, pp. 322, 324.

- 1 2 3 Olmedo Vera 1997, p.36.

- ↑ Foster 2002, p. 133.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, pp. 224–226.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, pp. 383, 387.

- ↑ Salisbury, Koumenalis & Barbara Moffett 2002. Martin & Grube 2000, p. 108. Sharer & Traxler 2006, p.387.

- ↑ Martin and Grube 2000, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Martin and Grube 2000, pp 192–193. Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 342.

- ↑ Martin and Grube 2000, pp. 200, 203.

- ↑ Martin and Grube 2000, pp. 203, 205.

- ↑ Miller 1999, pp. 134–135. Looper 2003, p. 76.

- ↑ Looper 1999, pp. 81, 271.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, p. 75.

- ↑ Martin and Grube 2000, p.19.

- 1 2 Martin and Grube 2000, p.21.

- ↑ Carmack 2003, p. 76.

- ↑ Carmack 2003, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, p. 89.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Miller 1999, p. 9.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 235. Miller 1999, p. 9.

- ↑ Stuart 1996, p. 149.

- ↑ Miller 1999, pp. 78, 80.

- ↑ Stuart 1996, p. 154.

- ↑ Borowicz 2003, p. 217.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, p. 163.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, p. 148.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, p. 149.

- ↑ Coe 1999, pp. 151–155.

- ↑ Becker 2004, p.134.

- ↑ Beeland 2007.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, p. 246.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, p. 248.

- ↑ Martin and Grube 2000, p. 226.

- 1 2 3 Masson 2012, p. 18237.

- ↑ Coe 1999, p. 152.

- ↑ Foster 2002, p. 60.

- ↑ Sharer 2000, p. 490.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, pp. 499–500.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, pp. 613, 616.

- ↑ Foias 2014, p. 15.

- 1 2 Masson 2012, p. 18238.

- 1 2 Arroyo 2001, p.38.

- ↑ Foias 2014, p. 17.

- ↑ Foias 2014, pp. 100–102.

- ↑ Andrews 1984, p. 589.

- ↑ Caso Barrera 2002, p. 17.

- ↑ Andrews 1984, pp. 589, 591.

- ↑ Estrada-Belli 2011, p. 52. Rice and Rice 2009, p. 17. Feldman 2000, p. xxi.

- 1 2 Jones 2000, p. 353.

- ↑ Rice and Rice 2009, p. 10. Rice 2009, p. 17.

- ↑ Cecil, Rice and Rice 1999, p. 788.

- ↑ Rice 2009, p. 17. Feldman 2000, p. xxi.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 717.

- ↑ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p. 5.

- ↑ Restall and Asselbergs 2007, p. 6.

- ↑ Lovell 2000, p. 398.

- ↑ Lenkersdorf 2004, p. 72.

- ↑ Lenkersdorf 2004, p. 78.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, pp. 759–760.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 763. Lovell 2005, p. 58. Matthew 2012, pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 763.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, pp. 764–765. Recinos 1986, pp. 68, 74.

- ↑ Schele and Mathews 1999, p.297. Guillemín 1965, p.9.

- ↑ Schele and Mathews 1999, p.298.

- ↑ Recinos 1986, p.110. del Águila Flores 2007, p.38.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, pp. 766–772.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, pp. 772–773.

- ↑ Jones 1998, p. xix.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 9.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 10.

- ↑ Zorich 2012, p. 29. Thompson 1932, p. 449.

- ↑ Sharer and Traxler 2006, p. 11.

- 1 2 Demarest 2004, p. 31.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, p. 32.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Koch 2013, pp. 1, 105.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, p. 34.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, pp. 37–38.

- 1 2 Demarest 2004, p. 38.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, p. 39.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, p. 41.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, p. 42.

- ↑ NASA Earth Observatory.

- 1 2 Demarest 2004, p. 44.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, p. 45.

- ↑ Foster 2002, p. 8.

- ↑ Demarest 2004, pp. 49–51.

References

- Acemoglu, Daron; James A. Robinson (2012). Why Nations Fail. London, UK: Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-71921-8. OCLC 805356561.

- Andrews, Anthony P. (Winter 1984). "The Political Geography of the Sixteenth Century Yucatan Maya: Comments and Revisions". Journal of Anthropological Research. Albuquerque, New Mexico, US: University of New Mexico. 40 (4): 589–596. ISSN 0091-7710. JSTOR 3629799. OCLC 1787802. (subscription required)

- Arroyo, Bárbara (July–August 2001). Enrique Vela, ed. "El Poslclásico Tardío en los Altos de Guatemala" [The Late Postclassic in the Guatemalan Highlands]. Arqueología Mexicana (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: Editorial Raíces. IX (50): 38–43. ISSN 0188-8218. OCLC 40772247.

- Becker, Marshall Joseph (2004). "Maya Heterarchy as Inferred from Classic-Period Plaza Plans". Ancient Mesoamerica. Cambridge University Press. 15: 127–138. doi:10.1017/S0956536104151079. ISSN 0956-5361. OCLC 43698811. (subscription required)

- Beeland, DeLene (2007-11-08). "UF study: Maya politics likely played role in ancient large-game decline". Gainesville, Florida, US: University of Florida News. Archived from the original on 2014-11-12. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- Borowicz, James (2003). "Images of Power and the Power of Images: Early Classic Iconographic Programs of the Carved Monuments of Tikal". In Geoffrey E. Braswell. The Maya and Teotihuacan: Reinterpreting Early Classic Interaction. Austin, Texas, US: University of Texas Press. pp. 217–234. ISBN 0-292-70587-5. OCLC 49936017.

- Carmack, Robert M. А. (March 2003). "Historical Antropological Perspective on the Maya Civilization". Social Evolution & History. Moscow, Russia: Uchitel. 2 (1): 71–115. ISSN 1681-4363. OCLC 50573883.

- Caso Barrera, Laura (2002). Caminos en la selva: migración, comercio y resistencia: Mayas yucatecos e itzaes, siglos XVII–XIX [Roads in the Forest: Migration, Commerce and Resistance: Yucatec and Itza Maya, 17th–19th Centuries] (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: El Colegio de México, Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 978-968-16-6714-6. OCLC 835645038.

- Cecil, Leslie; Prudence M. Rice; Don S. Rice (1999). J. P. Laporte; H. L. Escobedo, eds. "Los estilos tecnológicos de la cerámica Postclásica con engobe de la región de los lagos de Petén" [The Technological Styles of Postclassic Slipped Ceramics in the Petén Lakes Region] (PDF). Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala City, Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología. XII (1998): 788–795. OCLC 42674202. Retrieved 2012-11-26.

- Coe, Michael D. (1999). The Maya (Sixth ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28066-5. OCLC 40771862.

- del Águila Flores, Patricia (2007). "Zaculeu: Ciudad Postclásica en las Tierras Altas Mayas de Guatemala" [Zaculeu: Postclassic City in the Maya Highlands of Guatemala] (PDF) (in Spanish). Guatemala City, Guatemala: Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes. OCLC 277021068. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2011-08-06.

- Demarest, Arthur (2004). Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Forest Civilization. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53390-4. OCLC 51438896.

- Drew, David (1999). The Lost Chronicles of the Maya Kings. London, UK: Phoenix Press. ISBN 0-7538-0989-3. OCLC 59565970.

- Estrada-Belli, Francisco (2011). The First Maya Civilization: Ritual and Power Before the Classic Period. Abingdon, UK and New York, US: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-42994-8. OCLC 614990197.

- Foias, Antonia E. (2014) [2013]. Ancient Maya Political Dynamics. Gainesville, Florida, US: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-6089-7. OCLC 878111565.

- Foster, Lynn (2002). Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World. New York, US: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518363-4. OCLC 57319740.

- Guillemín, Jorge F. (1965). Iximché: Capital del Antiguo Reino Cakchiquel [Iximche: Capital of the Ancient Kaqchikel Kingdom] (in Spanish). Guatemala City, Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional de Guatemala. OCLC 1498320.

- Hammond, Norman; Duncan Pring; Rainer Berger; V. R. Switsur; A. P. Ward (1976-04-15). "Radiocarbon chronology for early Maya occupation at Cuello, Belize". Nature. Nature.com. 260 (260): 579–581. doi:10.1038/260579a0. ISSN 0028-0836. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- Hansen, Richard D.; Beatriz Balcárcel; Edgar Suyuc; Héctor E. Mejía; Enrique Hernández; Gendry Valle; Stanley P. Guenter; Shannon Novak (2006). J.P. Laporte; B. Arroyo; H. Mejía, eds. "Investigaciones arqueológicas en el sitio Tintal, Petén" [Archaeological investigations at the site of Tintal, Peten] (PDF). Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala City, Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología. XIX (2005): 739–751. OCLC 71050804. Retrieved 2011-08-19.

- Feldman, Lawrence H. (2000). Lost Shores, Forgotten Peoples: Spanish Explorations of the South East Maya Lowlands. Durham, North Carolina, US: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2624-8. OCLC 254438823.

- Jones, Grant D. (1998). The Conquest of the Last Maya Kingdom. Stanford, California, US: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804735223.

- Jones, Grant D. (2000). "The Lowland Maya, from the Conquest to the Present". In Richard E.W. Adams; Murdo J. Macleod. The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, Vol. II: Mesoamerica, part 2. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 346–391. ISBN 0-521-65204-9. OCLC 33359444.

- Koch, Peter O. (2013). John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood: Pioneers of Mayan Archaeology. Jefferson, North Carolina, US: McFarland. ISBN 9780786471072. OCLC 824359844.

- Lenkersdorf, Gudrun (2004) [1995]. "La resistencia a la conquista española en Los Altos de Chiapas". In Juan Pedro Viqueira; Mario Humberto Ruz. Chiapas: los rumbos de otra historia [Resistance to the Spanish Conquest in the Chiapas Highlands] (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: Centro de Investigaciones Filológicas with Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social (CIESAS). pp. 71–85. ISBN 968-36-4836-3. OCLC 36759921. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-13.

- Looper, Matthew G. (1999). "New Perspectives on the Late Classic Political History of Quirigua, Guatemala". Ancient Mesoamerica. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. 10 (2): 263–280. doi:10.1017/S0956536199101135. ISSN 0956-5361. OCLC 86542758.

- Love, Michael (December 2007). "Recent Research in the Southern Highlands and Pacific Coast of Mesoamerica". Journal of Archaeological Research. Springer Netherlands. 15 (4): 275–328. doi:10.1007/s10814-007-9014-y. ISSN 1573-7756.

- Lovell, W. George (2000). "The Highland Maya". In Richard E.W. Adams; Murdo J. Macleod. The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, Vol. II: Mesoamerica, part 2. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 392–444. ISBN 0-521-65204-9. OCLC 33359444.

- Lovell, W. George (2005). Conquest and Survival in Colonial Guatemala: A Historical Geography of the Cuchumatán Highlands, 1500–1821 (3rd ed.). Montreal, Canada: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-2741-9. OCLC 58051691.

- Martin, Simon; Nikolai Grube (2000). Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05103-8. OCLC 47358325.

- Masson, Marilyn A. (2012-11-06). "Maya collapse cycles". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Washington, DC, US: National Academy of Sciences. 109 (45): 18237–18238. doi:10.1073/pnas.1213638109. ISSN 1091-6490. JSTOR 41829886. (subscription required)

- Matthew, Laura E. (2012). Memories of Conquest: Becoming Mexicano in Colonial Guatemala (hardback). First Peoples. Chapel Hill, North Carolina, US: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3537-1. OCLC 752286995.

- Miller, Mary (1999). Maya Art and Architecture. London, UK and New York, US: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20327-X. OCLC 41659173.

- NASA Earth Observatory. "Maya Ruins". Greenbelt, Maryland, US: Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 2012-12-03. Retrieved 2006-04-28.

- Olmedo Vera, Bertina (1997). "The Mayas of the Classic Period". In A. Arellano Hernández; et al. The Mayas of the Classic Period. Mexico City, Mexico: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes (CONACULTA). pp. 9–99. ISBN 970-18-3005-9. OCLC 42213077.

- Popenoe de Hatch, Marion; Christa Schieber de Lavarreda (2001). J.P. Laporte; A.C. Suasnávar; B. Arroyo, eds. "Una revisión preliminar de la historia de Tak'alik Ab'aj, departamento de Retalhuleu" [A Preliminary Revision of the History of Takalik Abaj, Retalhuleu Department] (PDF). Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala City, Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología. XIV (2000): 990–1005. OCLC 49563126. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- Pugh, Timothy W.; Leslie G. Cecil (2012). "The contact period of central Petén, Guatemala in color". Social and Cultural Analysis, Department of. Faculty Publications. Nacogdoches, Texas, US: Stephen F. Austin State University. Paper 6.

- Recinos, Adrian (1986) [1952]. Pedro de Alvarado: Conquistador de México y Guatemala [Pedro de Alvarado: Conqueror of Mexico and Guatemala] (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Antigua Guatemala, Guatemala: CENALTEX Centro Nacional de Libros de Texto y Material Didáctico "José de Pineda Ibarra". OCLC 243309954.

- Restall, Matthew; Florine Asselbergs (2007). Invading Guatemala: Spanish, Nahua, and Maya Accounts of the Conquest Wars. University Park, Pennsylvania, US: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-02758-6. OCLC 165478850.

- Rice, Prudence M. (2009). "Who were the Kowoj?". In Prudence M. Rice; Don S. Rice. The Kowoj: identity, migration, and geopolitics in late postclassic Petén, Guatemala. Boulder, Colorado, US: University Press of Colorado. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-0-87081-930-8. OCLC 225875268.

- Rice, Prudence M.; Don S. Rice (2009). "Introduction to the Kowoj and their Petén Neighbors". In Prudence M. Rice; Don S. Rice. The Kowoj: identity, migration, and geopolitics in late postclassic Petén, Guatemala. Boulder, Colorado, US: University Press of Colorado. pp. 3–15. ISBN 978-0-87081-930-8. OCLC 225875268.

- Salisbury, David; Mimi Koumenalis; Barbara Moffett (19 September 2002). "Newly revealed hieroglyphs tell story of superpower conflict in the Maya world" (PDF). Exploration: the online research journal of Vanderbilt University. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Office of Science and Research Communications. OCLC 50324967. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-02. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

- Saturno, William A.; David Stuart; Boris Beltrán (2006-03-03). "Early Maya Writing at San Bartolo, Guatemala". Science. New Series. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 311 (5765): 1281–1283. doi:10.1126/science.1121745. ISSN 1095-9203. JSTOR 3845835. OCLC 863047799. PMID 16400112. (subscription required)

- Schele, Linda; Peter Mathews (1999). The Code of Kings: The language of seven Maya temples and tombs. New York, US: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-85209-6. OCLC 41423034.

- Schieber de Lavarreda, Christa; Miguel Orrego Corzo (2010). "La Escultura "El Cargador del Ancestro" y su contexto. Mesa Redonda: Pozole de signos y significados. Juntándonos en torno a la epigrafía e iconografía de la escultura preclásica. Proyecto Nacional Tak'alik Ab'aj, Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes, Dirección General del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural/IDAEH" [The "Ancestor Carrier" and its context. Round Table: A hotpot of signs and meanings. Linking us in turn to the epigraphy and iconography of Preclassic sculpture. Takalik Abaj National Project, Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Cultural and Natural Heritage/IDAEH]. Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala (in Spanish). Guatemala City, Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología. XXIII (2009). ISBN 9789929400375. OCLC 662509369.

- Sharer, Robert J. (2000). "The Maya Highlands and the Adjacent Pacific Coast". In Richard E.W. Adams; Murdo J. Macleod. The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, Vol. II: Mesoamerica, part 1. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 449–499. ISBN 0-521-35165-0. OCLC 33359444.

- Sharer, Robert J.; Loa P. Traxler (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th, fully revised ed.). Stanford, California, US: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4817-9. OCLC 57577446.

- Stuart, David (Spring–Autumn 1996). "Kings of Stone: A Consideration of Stelae in Ancient Maya Ritual and Representation". RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics. Cambridge, Massachusetts, US: President and Fellows of Harvard College acting through the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (29/30 The Pre-Columbian): 148–171. ISSN 0277-1322. JSTOR 20166947.

- Thompson, J. Eric S. (July–September 1932). "A Maya Calendar from the Alta Vera Paz, Guatemala". American Anthropologist. New Series. Wiley on behalf of the American Anthropological Association. 34 (3): 449–454. doi:10.1525/aa.1932.34.3.02a00090. ISSN 0002-7294. JSTOR 661903. OCLC 1479294. (subscription required)

- Zorich, Zach (November–December 2012). "The Maya Sense of Time". Archaeology. New York, US: Archaeological Institute of America. 65 (6): 25–29. ISSN 0003-8113. JSTOR 41804605. OCLC 1481828. (subscription required)