History of Poonch District

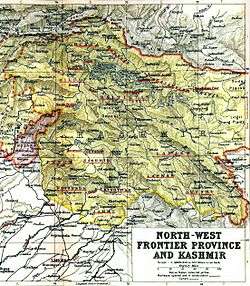

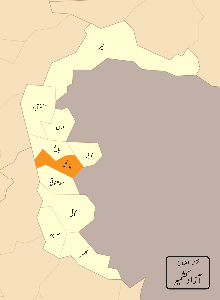

Poonch District was a district of Jammu and Kashmir, currently divided between India and Pakistan. The Pakistani part of Poonch District is part of its Azad Kashmir territory, whilst the Indian Poonch is part of the Jammu and Kashmir state. The capital of the Pakistan-controlled side is Rawalakot; while the capital of the Indian side is Poonch.

Early history

Ancient History

When Alexander invaded the lower Jhelum belt to fight Porus, the Jhelum valley region was known as Abhisara.[1] It is likely that the Kashmir Valley was under the control of this region. The Abhisaras submitted to the invader, along with Ambhi of Taxila, and the region was consolidated into the Alexander's empire.[2]

The Rajatarangini mentions Poonch under the name Paranotsa. Xuanzang in the 7th century transliterated it as Pun-nu-tso.[3]

Based on the Mahabharata evidence,[4] and evidence from 7th century Chinese traveler Xuanzang,[5] the districts of Rajaori, Poonch and Abhisara had been under the sway of the Republican Kambojas during epic times.[6]

At the time of Xuanzang's visit, the Kashmir Valley controlled all the territories adjacent to it in the south and the west, including Taxila, which is said to have been subjugated at a recent date.[7]

Sovereign State

Around 850CE, Poonch became a sovereign state ruled by Raja Nar, who was basically a horse trader. According to Rajatrangani, Raja Trilochanpal of Poonch gave a tough fight to Mahmood Ghaznavi who invaded this area in 1020. Ghaznavi failed to enter Kashmir, as he could not capture the fort of Lohara (modern day Loran, in district of Poonch).[8]

Mughal Era

In 1596, Mughal emperor Jahangir made Siraj-Ud-Din the ruler of Poonch. Siraj-Ud-Din and his descendants Raja Shahbaz Khan, Raja Abdul Razak, Raja Rustam Khan and Raja Khan Bahadur Khan ruled this area up to 1792.

Sikh Empire (1819–1852)

In 1819 this area was captured by Maharaja Ranjit Singh.[8] In 1822, Ranjit Singh anointed Gulab Singh as the Raja of Jammu and, in 1827, gave Poonch as a jagir to his brother Dhyan Singh. Dhyan Singh received the title of "Raja of Chibbal and Poonch" (Mirpur and Poonch districts as of 1947[9]) and subsequently appointed as the diwan (prime minister) in the Sikh court. As Gulab Singh expanded his kingdom surrounding the Kashmir Valley, Poonch was untouched.[10]

After the death of Ranjit Singh in 1839, the Sikh court fell into anarchy and palace intrigues took over. Dhyan Singh, his brother Suchet Singh as well as his son Hira Singh were murdered in the struggles.[11] Poonch was confiscated by the Sikh Durbar on the grounds that the Rajas had rebelled against the state and handed it over to Faiz Talib Khan of Rajouri.[12]

After the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845–1846) and the subsequent Treaties of Lahore and Amritsar, the entire territory between the Beas and the Indus rivers was transferred to Gulab Singh. He was declared the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir. Thus Poonch came under the control of Gulab Singh.[13] Gulab Singh reinstated the jagir of Poonch to Jawahir Singh, the eldest remaining son of Dhyan Singh.[12]

The brothers Jawahir Singh and Moti Singh were not satisfied. They put forward a claim to being independent rulers of Poonch, maintaining that they were entitled to a share in the 'family property' of all the territories controlled by Gulab Singh. The matter was adjudicated by Sir Frederick Currie, the British Resident in Lahore, in 1852, who confirmed that Gulab Singh was indeed their suzerain. The brothers were to give the Maharaja Gulab Singh a horse with gold trappings every year and consult him on all matters of importance.[14][15] The House of Poonch however continued to contest this arrangement right up to 1940.[16]

Jammu and Kashmir (1852–1947)

In 1852, the brothers Jawahir Singh and Moti Singh quarrelled and the Punjab Board of Revenue awarded a settlement. Moti Singh was awarded one-third of the family estate, representing the Poonch district of 1947, and Jawahir Singh was awarded two-thirds of the estate.[16][17]

In 1859, Jawahir Singh was accused of 'treacherous conspiracy' by Maharaja Ranbir Singh (r. 1857–1885), who succeeded Gulab Singh. The British agreed with the assessment and forced Jawahir Singh into exile in Ambala. Ranbir Singh paid Jawahir Singh an annual stipend of Rs. 100,000 until his death, and confiscated his territory afterwards because Jawahir Singh had no heirs. Moti Singh's son, Baldev Singh contested this action saying that the territory belonged to the descendants of Dhyan Singh. The British countered the claim saying Jawahir Singh forfeited his territory when he agreed to the annual stipend.[18]

After Maharaja Ranbir Singh was succeeded by Pratap Singh (r. 1885–1925), a 'Council of Administration' was imposed on Jammu and Kashmir by the British. The Council is said to have started encroaching on Poonch, egged on by Pratap Singh's brother Amar Singh. Complaints were made to the British, who continued the original line that Poonch was a feudatory of Jammu and Kashmir and ruled that it is an internal affair of Jammu and Kashmir.[18]

Raja Baldev Singh (r. 1892–1918), who succeeded Moti Singh, complained in 1895 that Jammu and Kashmir started referring to Poonch as a jagir, whereas he maintained that it was a 'state'. This was apparently a very emotive issue for Baldev Singh and, subsequently, to the residents of Poonch. Baldev Singh's successor Sukhdev Singh (r. 1918–1927) and Jagatdev Singh (r. 1928–1940) continued the complaints. In 1927, the British resident in Kashmir Evelyn Howell got involved and he advised Maharaja Hari Singh that, while Poonch was clearly subsidiary to Jammu and Kashmir, it was referred to as an illaqa in the original grant, meaning a dependency or simply a tract of country. The term jagir was not used. However, the Government of India did not wish to get involved.[19]

Jagatdev Singh ascended as the Raja in 1928 at a young age, and the reigning Maharaja Hari Singh (r. 1925–1949), son of Amar Singh, imposed a sanad (instruction) on him. The sanad mentioned, among others, that Poonch was a jagir and implemented several encroachments on the administration of Poonch. Frictions continued. In 1936, Jagatdev Singh sent a 'memorial' to the Viceroy of India, seeking a review of the relationship between Poonch and Jammu and Kashmir. The Government of India responded that, since Poonch was part of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, all submissions should be made through the Jammu and Kashmir government. The Resident of Jammu and Kashmir duly forwarded the complaint, with a comment that the British order of 1928, eventually based on Currie's original award, definitely settled the status of Poonch as a 'subordinate Jagirdar of Kashmir'. The relations between the Maharaja and the Raja were a 'domestic matter' on which the Government of India need not comment.[20]

With the death of Jagatdev Singh in 1940, his son Shiv Ratandev Singh became the new Raja while being a minor. Maharaja Hari Singh appointed a guardian, who was his military secretary, to look after the Raja's 'property'. The Raja's mother was prohibited from participating in the minority administration. In July 1940, a gathering of Poonch public passed a resolution expressing 'profound sorrow and deep indignation and resentment' at the Maharaja's proclamation and his description of Poonch as a jagir. By 1945, the Maharaja's administration was deeply unpopular in Poonch, especially among the families of servicemen, who contrasted it with that of their counterparts in Punjab.[21]

Administration

The taxation in the Poonch jagir is said to have been heavy. In the 1930s, the Raja of Poonch was said to have appropriated 40 percent of the jagir's annual income of Rs. 1 million. Out of this income, he paid Rs. 231 per year as tribute to the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir. The Raja of Poonch owned all the land in the jagir. The actual 'holders of land' were referred to as assamis (agents) of the Raja. Whereas proprietary rights were granted to landholders elsewhere in Kashmir following the Glancy Commission recommendations in 1933, the Poonchis did not benefit from the reforms due to the jagir's autonomy. For some unknown reason, the residents of the Mendhar tehsil were granted ownership rights, which further aggravated the resentment in the other tehsils.[22]

The Poonch jagir had its own officials, including a bureaucracy, police and a standing army of one company. However, local officials, most of whom were Hindus, were disgruntled because their salaries were lower than in the rest of state or in British India. Consequently, they were inefficient and corrupt.[23]

After the Maharaja Hari Singh started encroaching on the administration of Poonch starting in 1928, a dual system of rule was established. A resident administrator of the Maharaja was appointed in the Poonch jagir and further officials were loaned from the state. The Raja's courts had jurisdiction only in petty cases. All serious crimes were referred to the courts in Srinagar. The Raja of Poonch lost his prestige and power.[23]

The Maharaja also imposed additional taxes to generate his own revenue from the jagir. They included taxes on cattle and sheep, export/import taxes on items like soap and silk, and imaginative taxes on wives and widows. A 'horse tax' required a payment of 50 percent of the purchase price of a horse. Evidently, these taxes generated considerable resentment.[24]

Economy

Being a mountainous area, Poonch provided small farms with poor soil, but had high costs of living. The tax burden made the situation worse. Many Poonchi men worked outside the jagir to alleviate the situation. They worked in Punjab, the railways, British Indian army and the British merchant navy in Bombay.[25] The army was an especially important employer. It was said that every male Muslim in the jagir was, had been or would be a soldier in the British Indian army. During the World War I, 31,000 men from Jammu and Kashmir served in the army, a great majority of them from Poonch. During the World War II, over 60,000 men from Poonch served in the army, while the rest of the state contributed only about 10,000 men. The physical proximity of Poonch to the military recruiting grounds in Punjab, such as Sialkot and Rawalpindi, facilitated their enrolment. Poonchis enlisted as 'Punjabi Musalmans' and served in the Punjab Regiment.[26][27]

Division of Poonch

The Muslims of Poonch always resented the oppressive policies of the Dogra Maharaja of Jammu, after he took charge of Poonch in 1936. At the time of partition in 1947, there were rumours that Muslims were being massacred in Jammu. It enraged the Poonchies and they intensified the struggle for independence from Jammu. A major part of the district went to Azad Kashmir. During the 1947-48 war between India and Pakistan, Poonch city was under attack by the rebel Poonchies, Pakistani tribals and Pakistan army for about a year. It was in the month of November 1948 that Poonch city was relieved from the attack, to be re-united with the Indian-administered Kashmir.

See also

- Poonch District (AJK) - Administered by Pakistan.

- Poonch District (J&K) - Administered by India.

References

- ↑ Roy, Kumkum (2009), Historical Dictionary of Ancient India, Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 2–, ISBN 978-0-8108-5366-9

- ↑ Bamzai, Culture and Political History of Kashmir 1994, pp. 67-68.

- ↑ Bamzai, Culture and Political History of Kashmir 1994, p. 42.

- ↑ MBH 7.4.5; 7/91/39-40.

- ↑ Watters, Yuan Chawang, Vol I, p 284.

- ↑ Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 133, 219/220, Dr H. C. Raychaudhury, Dr B. N. Mukerjee; A History of India, p 269-71, N. R. Ray, N. K. Sinha; Journal of Indian History, p 304, University of Allahabad. Department of Modern Indian History, University of Kerala - 1921.

- ↑ Bamzai, Culture and Political History of Kashmir 1994, p. 117.

- 1 2 History of Poonch, Official web site of the Poonch District (Jammu and Kashmir), retrieved September 2016.

- ↑ A peep into Bhimber, Daily Excelsior, 6 November 2016.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, pp. 31-40.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, Chapters III, IV.

- 1 2 Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, p. 121.

- ↑ Satinder Singh, Raja Gulab Singh's Role 1971, pp. 52-53.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, pp. 121-123.

- ↑ Mridu Rai, Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects 2004, p. 48.

- 1 2 Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History 2013, p. 232.

- ↑ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, p. 123.

- 1 2 Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History 2013, p. 233.

- ↑ Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History 2013, pp. 233-234.

- ↑ Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History 2013, pp. 234-236.

- ↑ Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History 2013, pp. 237-238.

- ↑ Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History 2013, pp. 30-31.

- 1 2 Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History 2013, pp. 29-30.

- ↑ Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History 2013, p. 30.

- ↑ Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History 2013, p. 28.

- ↑ Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History 2013, p. 31.

- ↑ Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict 2003, p. 41.

Bibliography

- Bamzai, P. N. K. (1994), Culture and Political History of Kashmir, M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd., ISBN 978-81-85880-31-0

- Behera, Navnita Chadha (2007), Demystifying Kashmir, Pearson Education India, ISBN 8131708462

- Huttenback, Robert A. (1961), "Gulab Singh and the Creation of the Dogra State of Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh" (PDF), The Journal of Asian Studies, 20 (4): 477–488, doi:10.2307/2049956

- Panikkar, K. M. (1930). Gulab Singh. London: Martin Hopkinson Ltd.

- Rai, Mridu (2004), Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects: Islam, Rights, and the History of Kashmir, C. Hurst & Co, ISBN 1850656614

- Schofield, Victoria (2003) [First published in 2000], Kashmir in Conflict, London and New York: I. B. Taurus & Co, ISBN 1860648983

- Singh, Bawa Satinder (1971), "Raja Gulab Singh's Role in the First Anglo-Sikh War", Modern Asian Studies, 5 (1): 35–59, JSTOR 311654

- Snedden, Christopher (2013) [first published as The Untold Story of the People of Azad Kashmir, 2012], Kashmir: The Unwritten History, HarperCollins India, ISBN 9350298988