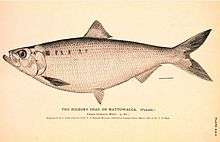

Hickory shad

| Alosa mediocris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Clupeiformes |

| Family: | Clupeidae |

| Genus: | Alosa |

| Species: | A. mediocris |

| Binomial name | |

| Alosa mediocris (Mitchill, 1814) | |

Hickory shad (Alosa mediocris) is a member of the herring family Clupeidae, ranging along the East Coast of the United States from Florida to the Gulf of Maine. It is an anadromous fish species, meaning that it spawns in freshwater portions of rivers but spends most of its life at sea. It is subject to fishing, both historic and current, but it is often confused with or simply grouped together with catch statistics for American shad (Alosa sapidissima).

Distribution, habitat, and life history

Hickory shad ranges from northern Florida to the Gulf of Maine. The largest populations occur in Chesapeake Bay and coastal North Carolina (Munroe 2002). It is a schooling anadromous species that inhabits marine waters, probably never far from land. Adults enter estuaries and freshwater tributaries from the St. John's River, Florida, to the Patuxent River, Maryland,to spawn during the spring. Their oceanic movements are poorly documented (Hardy 1978; Cooper 1983; Rulifson 1994).

Spawning occurs from December to June, earliest in Florida and later with increasing latitude (Hardy 1978; Harris et al. 2007). The slightly adhesive and demersal eggs, approximately 1 mm in diameter, appear to be dispersed at random over gravel bars in moderate current. After water hardening, the eggs become semi-buoyant and develop as they drift along the bottom (Mansueti 1962; Hardy 1978; Cooper 1983). Fecundity ranges from 43,000 – 475,000 eggs per female, and, although the developmental stages of eggs, larvae, and juveniles have been described, little is known concerning the distribution, ecology, and growth rates of these early life stages (Mansueti 1962; Hardy 1978).

Hickory shad live to seven years (Harris et al. 2007). Both sexes mature at 2–4 years and can repeat spawn. Females are larger than males; in Florida, the average female is 37 cm fork length and the average male is 34 cm fork length (Harris et al. 2007).

Hickory shad are piscivorous, feeding primarily on small fishes, although crustaceans and squid contribute to their diet (Cooper 1983; Munroe 2002). One study showed that their diet on the spawning grounds was almost exclusively fish (97% by weight; Harris et al. 2007).

Recreational fishery

Hickory shad have a relatively low commercial value; however, there is an increasingly popular recreational fishery throughout the mid-Atlantic states. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, hickory shad articles appeared in sport fishing magazines. Headlines such as “the tough fighting hickory shad swarm near the rock-studded fall line…” (Sports Afield 1988), and “feast on Rappahannock River hickory shad action” (Field & Stream 1992) brought attention to the fishery. Subsequently, specialty magazines (Fly Fisherman 2002) and sports sections in national newspapers (i.e., The Washington Post, 1988, 2000) began proclaiming the excitement of hickory shad fishing (“HICKORY SHAD ARE RUNNING!”) and the recovery of the fishery. In the two most recent years of a North Carolina creel survey (2004-2005), hickory shad – a fish only present for two months of the year – moved from sixth to the fourth most targeted fish by coastal anglers (Murauskas and Mumford 2006).

Literature

Most information about this species is contained in federal and state documents and management plans or theses from universities. Federal publications include reports from the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s (ASMFC) Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Shad and River Herring (ASMFC 1999; ASMFC 2001). Prominent publications by state agencies include reports based on fishery monitoring programs in Connecticut (Gephard and McMenemy 2004), Pennsylvania, Maryland (Chesapeake Bay Agreement 2000), North Carolina (NCDMF and NCWRC 2004), South Carolina, Georgia (Street and Adams 1969; Street 1969; Ulrich et al. 1979), and Florida (McBride 2000; Harris and McBride 2004; Harris et al. 2007; McBride and Holder 2008; McBride and Matheson 2011). A few publications address coast-wide and/or genus-level stock status and management issues (Rulifson 1994; Yako et al. 2002). The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service published a useful series that includes egg, larvae, and juvenile development descriptions of hickory shad (Hardy 1978). A recent review of hickory shad in Chesapeake Bay places management of this species in an ecosystem context (Alosine Species Team, 2011). Three Master of Science theses include: Pate, 1972 (North Carolina State University), Batsavage, 1997 (East Carolina University), and Watkinson, 2004 (Virginia Commonwealth University).

Although hickory shad research has been limited, other clupeids, especially Alosa species in the United States, have received more attention (e.g., Limburg and Waldman 2003). American shad (A. sapidissima), which overlaps in distribution with hickory shad, has been frequently studied (Atkinson 1951; Dodson and Dohse 1984; Melvin et al. 1986; Quinn and Adams 1996; Leonard and McCormick 1999a, 1999b; Leonard et al. 1999; Waters et al. 2000; Limburg and Waldman 2003; McBride and Matheson 2011).

References

- Alosine Species Team. (2011). Alosine Species Team Background and Issues Briefs. In: Ecosystem Based Fisheries Management for Chesapeake Bay.(http://www.mdsg.umd.edu/images/uploads/siteimages/00-Alosines_Briefs-FINAL.pdf)

- Atkinson, C.E. 1951. Feeding habits of adult shad (Alosa sapidissima) in fresh water. Ecology 32(3):556-557.

- ASMFC. 1999. Fisheries Management Report No. 35. Amendment 1 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Shad and River Herring. 1444 Eye St. NW, Washington, DC.

- ASMFC. 2001. Review of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Fishery Management Plan for Shad and River Herring (Alosa sp.). 1444 Eye St. NW, Washington, DC.

- Batsavage, C.F. 1997. Life history aspects of the hickory shad (Alosa mediocris) in the Albemarle Sound/Roanoke River Watershed, North Carolina. M.S. Thesis, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina.

- Batsavage, C.F., and R.A. Rulifson. 1998. Life history aspects of the hickory shad (Alosa mediocris) in the Albemarle Sound/Roanoke River Watershed, North Carolina. Completion report for project M6057. North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries, Morehead City, North Carolina.

- Bentzen, P., W.C. Leggett, and G.G. Brown. 1993. Genetic relationships among the shads (Alosa) revealed by mitochondrial DNA analysis. Journal of Fish Biology 43:909-917.

- Chesapeake Bay Agreement. 2000. The Renewed Bay Agreement. Retrieved May 26, 2006. http://dnrweb.dnr.state.md.us/bay/res_protect/c2k/index.asp.

- Cooper, E.L. 1983. Fishes of Pennsylvania and the Northeastern United States. Penn State University Press, University Park and London. pp. 47–50.

- Dodson, J.J. and L.A. Dohse. 1984. A model of olfactory-mediated conditioning of directional bias in fish migrating in reversing tidal currents based on the homing migration of American shad (Alosa sapidissima). pp. 263–281 in J.D. McCleave, G.P. Arnold, J.J. Dodson, and W.H. Neill, editors. Mechanisms of migration in fishes. Plenum Press, New York.

- Field & Stream. April 1992. Feast on Rappahannock River hickory shad action. 96(12):70A.

- Fly Fisherman. September 2002. Shad restoration continues. 33(6):27.

- Gephard, S. and J. McMenemy. 2004. An overview of the program to restore Atlantic salmon and other diadromous fishes to the Connecticut River with notes on the current status of these species in the river. American Fisheries Society monograph No. 9, pp. 287–317.

- Hardy, J.D. 1978. Development of fishes of the Mid-Atlantic bight: An atlas of egg, larval and juvenile stages; Acipenseridae through Ictaluridae. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Volume 1:75-88

- Harris, J., and R. McBride. 2004. A review of the potential effects of water level fluctuation on diadromous fish populations for MFL determinations. St. John’s River Water Management District, Contract No. SG346AA. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

- Harris, Julianne E., R. S. McBride, and R. O. Williams. 2007. Life history of hickory shad in the St. Johns River, Florida. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 136(6): 1463-1471. DOI: 10.1577/T06-187.1

- Leonard, J.B.K, and S.D. McCormick. 1999a. Effects of migration distance on whole-body and tissue-specific energy use in American shad (Alosa sapidissima). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 56(7):1159-71.

- Leonard, J.B.K., and S.D. McCormick. 1999b. Changes in haematology during upstream migration in American shad. Journal of Fish Biology 54:1218-1230.

- Leonard, J.B.K., J.F. Norieka, B. Kynard, and S.D. McCormick. 1999. Metabolic rates in an anadromous clupeid, the American shad (Alosa sapidissima). Journal of Comparative Physiology and Biology 169:287-295.

- Limburg, K.E. and J.R. Waldman, editors. 2003. Biodiversity, status, and conservation of the world’s shads. American Fisheries Society Symposium 35. Bethesda, Maryland.

- Mansueti, R.J. 1962. Eggs, larvae, and young of the hickory shad, Alosa mediocris, with comments on its ecology in the estuary. Chesapeake Science 3: 173-205.

- McBride, Richard S., and Richard E. Matheson. (2011). Florida's diadromous fishes: biology, ecology, conservation, and management. Florida Scientist. 74(3): 187-213.

- McBride, Richard S., and Jay C. Holder (2008). A Review and Updated Assessment of Florida's Anadromous Shads: American Shad and Hickory Shad. North American Journal of Fisheries Management. 28(6): 1668-1686. DOI: 10.1577/M07-066.1

- McBride, R.S. 2000. Florida’s shad and river herrings (Alosa species): A review of population and fishery characteristics. Florida Marine Research Institute Technical Reports No. 5.

- Melvin, G.D., M.J. Dadswell, and J.D. Martin. 1986. Fidelity of American shad, Alosa sapidissima (Clupeidae), to its river of previous spawning. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 43:640-646.

- Murauskas, J.G. and D.G. Mumford. 2006. North Carolina cooperative striped bass creel survey in the central and southern management area (CSMA). Grant F-79, Seg. 2. N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Division of Marine Fisheries, Morehead City, North Carolina.

- Munroe, T.A. (2002) Herrings. Family Clupeidae. In: Bigelow and Schroeder's Fishes of the Gulf of Maine. B. B. Collette and G. Klein-MacPhee (Eds.). Smithsonian Institution Press.

- NCDMF and NCWRC. 2004. Shad and River Herring Fisheries and Monitoring Programs in North Carolina – 2003: Report to the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Shad and River Herring Technical Committee. Raleigh, North Carolina.

- Pate, P.P. 1972. Life history aspects of the hickory shad, Alosa mediocris (Mitchell), in the Neuse River, North Carolina. M.S. Thesis, North Carolina State University. Raleigh, North Carolina.

- Perkins, R.J., and M.D. Dahlberg. 1971. Fat cycles and condition factors of Altamaha River shad. Ecology 52(2):359-362.

- Quinn, T.P. and D.J. Adams. 1996. Environmental changes affecting the migratory timing of American shad and sockeye salmon. Ecology 77(4):1151-1162.

- Rulifson, R.A. 1994. Status of anadromous Alosa along the East Coast of North America. Anadromous Alosa symposium. Tidewater Chapter, American Fisheries Society. pp. 134–158.

- Sports Afield. March 1988. Rappahannock shad. 199(3):70.

- Street, M.W. 1969. Fecundity of the hickory shad in the Altamaha River, Georgia. Contribution Series No. 14. Georgia Game and Fish Commission, Marine Fisheries Division.

- Street, M.W. and J.G. Adams. 1969. Aging of hickory shad and blueback herring in Georgia by the scale method. Contribution Series No. 18. Georgia Game and Fish Commission, Marine Fisheries Division.

- The Washington Post. April 3, 1988. Hickory Shad are Running! Sports section, pp. c. 16.

- The Washington Post. May 11, 2000. Md. Welcomes back the shad; biologists touting victory for rivers’ spawning program. pg. b. 01.

- Ulrich, G., N. Chipley, J.W. McCord, D. Cupka, J.L. Music, and R.K. Manhood. 1979. Development of fishery management plans for selected anadromous fishes in South Carolina and Georgia. South Carolina Wildlife and Marine Resources Department, Charleston, South Carolina.

- Waters, J.M., J.M. Epifanio, T. Gunter, and B.L. Brown. 2000. Homing behavior facilitates subtle genetic differentiation among river populations of Alosa sapidissima: microsatellites and mtDNA. Journal of Fish Biology 56:622-636.

- Watkinson, E.R. 2004. Age, growth, and fecundity of hickory shad (Alosa mediocris) in Virginia coastal river. M.S. thesis. Virginia Commonwealth University. Richmond, Virginia.

- Yako, L.A., M.E. Mather, and F. Juanes. 2002. Mechanisms for migration of anadromous herring: an ecological basis for effective conservation. Ecological Applications 12(2):521-534.