Herbicidal warfare

Herbicidal warfare is the use of substances primarily designed to destroy the plant-based ecosystem of an area. Although herbicidal warfare use chemical substances, its main purpose is to disrupt agricultural food production and/or to destroy plants which provide cover or concealment to the enemy, not to asphyxiate or poison humans and/or destroy human-made structures. Herbicidal warfare has been forbidden by the Environmental Modification Convention since 1978, which bans "any technique for changing the composition or structure of the Earth's biota".[1]

History

Modern day herbicidal warfare resulted from military research discoveries of plant growth regulators in the Second World War, and is therefore a technological advance on the scorched earth practices by armies throughout history to deprive the enemy of food and cover.

Work on military herbicides began in England in 1940, and by 1944, the United States joined in the effort. Even though herbicides are chemicals, due to their mechanism of action (growth regulators), they are often considered a means of biological warfare. Over 1,000 substances were investigated by the war's end for phytotoxic properties, and the Allies envisioned using herbicides to destroy Axis crops. British planners did not believe herbicides were logistically feasible against Germany.

In May 1945, USAAF General Victor E. Betrandias advanced a proposal to his superior General Arnold to use of ammonium thiocyanate to reduce rice crops in Japan as part of the bombing raids on their country. This was part of larger set of proposed measures to starve the Japanese. The plan calculated that ammonium thiocyanate would not be seen as "gas warfare" because the substance was not particularly dangerous to humans. On the other hand, the same plan envisaged that if the U.S. were to engage in "gas warfare" against Japan, then mustard gas would be an even more effective rice crop killer. The Joint Target Group rejected the plan as tactically unsound, but expressed no moral reservations.[2]

Malaya

During the Malayan Emergency, Britain was the first nation to employ herbicides and defoliants in order to deprive the communist insurgents of cover and targeting food crops as part of the starvation campaign in the early 1950s. Documents showed that the British "Trioxone" used in Malaya was virtually identical in composition to the Agent Orange later used by the U.S. in Vietnam. It was used to thin jungle trails to limit ambushes, and destruction of native agriculture. For example, in the summer of 1952, 500 hectares were sprayed with 90,000 liters of "Trioxone" from fire engines. The British found it difficult to operate the machinery in jungle conditions and in full protective gear. The denial of food was considered a decisive weapon in countering the insurgency, so "bandit crops" were sprayed from aircraft.[3]

Discussions in the British government centered on avoiding the thorny issue of whether herbicidal warfare was in violation of the 1925 Geneva Protocol, which prohibited chemical warfare in rather general terms. The British were keen to avoid accusations like the allegations of biological warfare in the Korean War leveled against the U.S. The British government found that the simplest solution was to deny that a war was going on in Malaya. They declared the insurgency to be an internal security matter, thus the use of herbicidal agents was a matter of police action, much like the use of CS gas for riot control.[3]

Historical records of DOW chemical show that "Super Agent Orange", also called DOW Herbicide M-3393, was Agent Orange that was mixed with picloram. Super Orange was known to have been tested by representatives from Fort Detrick and DOW chemical in Texas, Puerto Rico, and Hawaii and later in Malaysia in a cooperative project with the International Rubber Research Institute.[4]

Many Commonwealth personnel who handled and/or used Agent Orange during, and in the decades after, the conflict suffered from serious exposure to dioxin and Agent Orange, which also caused major soil erosion to areas of Malaya. An estimated 10,000 civilians and insurgents in Malaya also suffered heavily from the effects of the defoliant (though many historians agree it was likely more than this number given that Agent Orange was used on a large scale in the Malayan conflict and unlike the U.S., the British government manipulated the numbers and kept its secret very tight in fear of negative world public opinion).[5][6][7]

Vietnam War

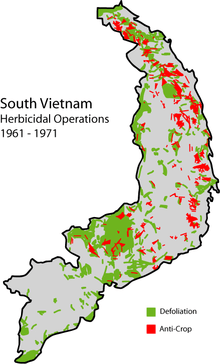

The United States used herbicides in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War. Success with Project AGILE field tests with herbicides in South Vietnam in 1961 and inspiration by the British use of herbicides and defoliants during the Malayan Emergency in the 1950s led to the formal herbicidal program Trail Dust (1961–1971). Operation Ranch Hand, a U.S. Air Force program to use C-123K aircraft to spray herbicides over large areas was one of many programs under Operation Trail Dust. The aircrews charged with spraying the defoliant used a sardonic motto-"Only you can prevent forests"-a shortening of the U.S. Forest Services famous warning to the general public "Only you can prevent forest fires". The United States and its allies officially claims that herbicidal and incendiary agents like napalm fall outside the definition of "chemical weapons" and that Britain set the precedent by using them during the Malayan Emergency.

Ranch Hand started as a limited program of defoliation of border areas, security perimeters, and crop destruction. As the conflict continued, the anti-crop mission took on more prominence, and (along with other agents) defoliants became used to compel civilians to leave Viet Cong-controlled territories for government-controlled areas. It was also used experimentally for large area forest burning operations that failed to produce the desired results.

Defoliation was judged in 1963 as improving visibility in jungles by 30 - 75% horizontally, and 40 - 80% vertically. Improvements in delivery systems by 1968 increased this to 50 - 70% horizontally, and 60 - 90% vertically. Ranch Hand pilots were the first to make an accurate 1:125,000 scale map of the Ho Chi Minh trail south of Tchpone, Laos by defoliating swaths perpendicular to the trail every half mile or so.

Use of herbicides in Vietnam caused a shortage of commercial pesticides in mid-1966 when the Defense Department had to use powers under the Defense Production Act of 1950 to secure supplies.

The concentration of herbicides sprayed in Operation Ranch Hand was more than an order of magnitude greater than that in domestic use. Approximately 10% of the land surface of South Vietnam was sprayed—about 17,000 square kilometers. About 85% of the spraying was for defoliation and about 15% was for crop destruction.[8]

Types of herbicides

The United States had technical military symbols for herbicides that have since been replaced by the more common color code names derived from the banding on shipping drums. The US further distinguished between tactical herbicides, which were to be used in combat operations and commercial herbicides, which used in and around military bases, etc.[9]

In 1966 the United States Defense Department claimed that herbicides used in Vietnam were not harmful to people or the environment. In 1972 it was advised that a known impurity precluded the use of these herbicides in Vietnam and all remaining stocks should be returned home. In 1977 the United States Air Force destroyed its stocks of Agent Orange 200 miles west of Johnston Island on the incinerator ship M/T Vulcanus. The impurity, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) was a suspected carcinogen that may have affected the health of over 17,000 United States servicemen, 4,000 Australians, 1,700 New Zealanders, Koreans, countless Vietnamese soldiers and civilians, and with over 40,000 children of veterans possibly suffering birth defects from herbicidal warfare.

Decades later the lingering problem of herbicidal warfare remains as a dominant issue of United States-Vietnam relations. In 2003, a coalition of Vietnamese survivors and long-term victims of Agent Orange sued a number of American-based and multinational chemical corporations for damages related to the manufacture and use of the chemical. A federal judge rejected the suit, claiming that the plaintiff's claim of direct responsibility was invalid.

See also

- E14 munition

- E77 balloon bomb

- Enterotoxin

- M115 bomb

- Mycotoxin

- U.S. Army Biological Warfare Laboratories

- War on Drugs#Aerial herbicide application

References

- ↑ "Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques". UN. 10 December 1976. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ↑ John David Chappell (1997). Before the Bomb: How America Approached the End of the Pacific War. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-0-8131-7052-7.

- 1 2 Bruce Cumings (1998). The Global Politics of Pesticides: Forging Consensus from Conflicting Interests. Earthscan. p. 61.

- ↑ "Operational Evaluation of Super-Orange" via National Security Archives at George Washington University. retrieved 10-24-12

- ↑ Pesticide Dilemma in the Third World: A Case Study of Malaysia. Phoenix Press. 1984. p. 23.

- ↑ Arnold Schecter, Thomas A. Gasiewicz (4 July 2003). Dioxins and Health. pp. 145–160.

- ↑ Albert J. Mauroni (July 2003). Chemical and Biological Warfare: A Reference Handbook. pp. 178–180.

- ↑ Mark Wheelis; Lajos Rózsa (2009). Deadly Cultures: Biological Weapons since 1945. Harvard University Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-674-04513-2.

- ↑ Alvin L. Young, The History of the US Department of Defense Programs for the Testing, Evaluation, and Storage of Tactical Herbicides, December 2006, www.dod.mil/pubs/foi/operation_and_plans/NuclearChemicalBiologicalMatters/TacticalHerbicides.pdf. A more abbreviated version: doi:10.1007/978-0-387-87486-9_2

Further reading

- Martini, Edwin A. (2013). "Hearts, Minds, and Herbicides: The Politics of the Chemical War in Vietnam". Diplomatic History. 37 (1): 58–84. doi:10.1093/dh/dhs003.

- Westing, A. H. (1989). "Herbicides in Warfare: The Case of Indochina" (PDF). In Bourdeau, P.; et al. Ecotoxicology and Climate. Stanford University, Department of Global Ecology.