Street art

Street art is visual art created in public locations, usually unsanctioned artwork executed outside of the context of traditional art venues. The term gained popularity during the graffiti art boom of the early 1980s and continues to be applied to subsequent incarnations. Stencil graffiti, wheatpasted poster art or sticker art, and street installation or sculpture are common forms of modern street art. Video projection, yarn bombing and Lock On sculpture became popularized at the turn of the 21st century.

The terms "urban art", "guerrilla art", "post-graffiti" and "neo-graffiti" are also sometimes used when referring to artwork created in these contexts.[1] Traditional spray-painted graffiti artwork itself is often included in this category, excluding territorial graffiti or pure vandalism.

Street art is often motivated by a preference on the part of the artist to communicate directly with the public at large, free from perceived confines of the formal art world.[2] Street artists sometimes present socially relevant content infused with esthetic value, to attract attention to a cause or as a form of "art provocation".[3]

Street artists often travel between countries to spread their designs. Some artists have gained cult-followings, media and art world attention, and have gone on to work commercially in the styles which made their work known on the streets.

Background

Street art is a form of artwork that is displayed in a community on its surrounding buildings, streets, and other publicly viewed surfaces. Many pieces of street art come in the form of guerrilla art, which is a work that is composed to make a public statement about the society that the artist lives within. The work of street artists has moved from the beginnings of graffiti and vandalism to modern day guerrilla art where the artists are working to get powerful messages across to the viewers.[4]

Street art can come in many forms as in recent years, the term has become an umbrella term for any work of art that is created or placed in a public area. Included within this term, are certain works of graffiti that have been decidedly labeled as works of art rather than works of vandalism. Due to the very subtle difference between street art and graffiti, it has come into debate for many whether certain works quality as art or not.[5] While the difference between the two may be subtle, it is used as a differentiator for those who review and analyze the works everyday.

Artists have challenged art by situating it in non-art contexts. Street artists do not aspire to change the definition of an artwork, but rather to question the existing environment with its own language.[2] The motivations and objectives that drive street artists are as varied as the artists themselves. ‘Street’ artists attempt to have their work communicate with everyday people about socially relevant themes in ways that are informed by esthetic values without being imprisoned by them. There is a strong current of activism and subversion in urban art. Street art can be a powerful platform for reaching the public and a potent form of political expression for the oppressed, or people with little resources to create change.[6] Common variants include adbusting, subvertising and other culture jamming, the abolishment of private property and reclaiming the streets.

Some street artists use "smart vandalism" as a way to raise awareness of social and political issues.[7] Other street artists simply see urban space as an untapped format for personal artwork, while others may appreciate the challenges and risks that are associated with installing illicit artwork in public places. A universal motive of most, if not all street art, is that adapting visual artwork into a format which utilizes public space allows artists who may otherwise feel disenfranchised to reach a much broader audience than traditional artwork and galleries normally allow.

Whereas traditional graffiti artists have primarily used free-hand aerosol paints to produce their works,[8] "street art" encompasses many other media and techniques, including: LED art, mosaic tiling, murals, stencil art, sticker art, "Lock On" street sculptures, street installations, wheatpasting, woodblocking, and yarn bombing. New media forms such as projection onto large city buildings are an increasingly popular tool for street artists—and the availability of cheap hardware and software allows street artists to become more competitive with corporate advertisements. Much like open source software, artists are able to create art for the public realm from their personal computers, similarly creating things for free which compete with companies making things for profit.[9]

Street art is a topical issue. Some people consider it a crime, others consider it a form of art.[10] Street artists may be charged with vandalism, malicious mischief, intentional destruction of property, criminal trespass, or antisocial behavior. Legal definitions vary between jurisdictions.[11] Some in society have transitioned from disdain to quiet acceptance. In some quarters acceptance has morphed into outright love instigating a race to purchase this urban craft.[12] In some cities, it is unlawful for landowners to allow any graffiti on their property if it’s visible from any other public or private property.

Origins

Slogans of protest and political or social commentary graffitied onto public walls are the precursor to modern graffiti and street art, and continue as one aspect of the genre. Street art in the form of text or simple iconic graphics in the vein of corporate icons become well-known yet enigmatic symbols of an area or an era.[13]

Some credit the Kilroy Was Here graffiti of the World War II era as one such early example; a simple line-drawing of a long-nosed man peering from behind a ledge. Author Charles Panati indirectly touched upon the general appeal of street art in his description of the "Kilroy" graffiti as "outrageous not for what it said, but where it turned up".[14]

Much of what can now be defined as modern street art has well-documented origins dating from New York City's graffiti boom, with its infancy in the 1960s, maturation in the 1970s, and peaking with the spraypainted full-car subway train murals of the 1980s centered in the Bronx.

As the 1980s progressed, a shift occurred from text-based works of early in the decade to visually conceptual street art such as Richard Hambleton's shadow figures (pictured above).[15] These years coincide with Keith Haring's subway advertisement subversions and Jean-Michel Basquiat's SAMO tags. What is now recognized as "street art" had yet to become a realistic career consideration, and offshoots such as stencil graffiti were in their infancy. Wheatpasted poster art used to promote bands and the clubs where they performed evolved into actual artwork or copy-art and became a common sight during the 1980s in cities worldwide. The group working collectively as AVANT were also active in New York during this period.[16] Punk rock music's subversive ideologies were also instrumental to street art's evolution as an art form during the 1980s. Some of the anti-museum mentality can be attributed to the ideology of F.T. Marinetti who in 1909 wrote the “Manifesto of Futurism”. A famous quote from that book said, “we will destroy all the museums”.[17] Many street artists claim we do not live in a museum so art should be in public places with no tickets.[17]

Early iconic works

The northwest wall of the intersection at Houston Street and the Bowery in New York City has been a target of artists since the 1970s.

The site, now sometimes referred to as the Bowery Mural, originated as a derelict wall which graffiti artists used freely. Keith Haring once commandeered the wall for his own use in 1982. After Haring, a stream of well-known street artists followed, until the wall had gradually taken on prestigious status. By 2008, the wall became privately managed and made available to artists by commission or invitation only.

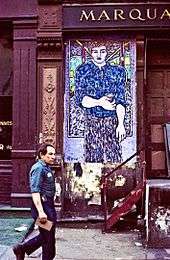

A series of I AM THE BEST ARTIST René murals painted by René Moncada began appearing on the streets of SoHo in the late 1970s. René has described the murals as a thumb in the nose to the art community he felt he'd helped pioneer but by which he later felt ignored.[13][18] Recognized as an early act of "art provocation",[3] they were a topic of conversation and debate at the time, and related legal conflicts raised discussion about intellectual property, artist's rights, and the First Amendment.[19][20][21][22] The ubiquitous murals (pictured above) also became a popular backdrop to photographs taken by tourists and art students, and for advertising layouts and Hollywood films.[23][24][25] IATBA murals were often defaced, only to be repainted by René.[3][26]

René Moncada: I AM THE BEST ARTIST René, New York (1986)

René Moncada: I AM THE BEST ARTIST René, New York (1986) John Fekner: No TV, street installation, New York (1980)

John Fekner: No TV, street installation, New York (1980) Shepard Fairey: André the Giant has a Posse, sticker art (c.1989)

Shepard Fairey: André the Giant has a Posse, sticker art (c.1989)

Exhibitions

In 1981, Washington Project for the Arts held an exhibition entitled Street Works, which included urban art pioneers such as John Fekner, Fab Five Freddy and Lee Quinones working directly on the streets.[27]

Fekner, who once defined street art as "all art on the street that’s not graffiti", is included in Cedar Lewisohn’s book Street Art: The Graffiti Revolution, which accompanied the 2008 Street Art exhibition at the Tate Modern in England, of which Lewisohn was the curator.[27]

Commercial crossover

Some street artists have earned international attention for their work and have made a full transition from street art into the mainstream art world — some while continuing to produce art on the streets. Keith Haring was among the earliest wave of street artists in the 1980s to do so. Traditional graffiti and street art motifs have also increasingly been incorporated into mainstream advertising, with many instances of artists contracted to work as graphic designers for corporations. Graffiti artist Haze has provided font and graphic designs for music acts such as the Beastie Boys and Public Enemy. Shepard Fairey's street posters of then-presidential candidate Barack Obama were reworked by special commission for use in the presidential campaign. A version of the artwork also appeared on the cover of Time magazine. It is also not uncommon for street artists to start their own merchandising lines.

As street art has become more accepted by the general public, most likely due to its artistic recognition and the high-profile status of Banksy and other graffiti artists. This has led street art to become one of the 'sights to see' in many European cities. Some street artists now provide tours of local street art and are able to share their knowledge, explaining the ideas behind many works, the reasons for tagging and the messages portrayed in a lot of graffiti work. Berlin, London, Paris, Hamburg and other cities all have popular street art tours running all year round. In London alone there are supposedly 10 different graffiti tours you can go on [28] many of these organisations such as, Alternative London,[29] ParisStreetArt,[30] AlternativeBerlin,[31] to name but a few, pride themselves on working with the local street artists, so visitors get an authentic experience and not just a rehearsed script.

Many of these guides/artists are painters, fine art graduates and other creative professions that have found street graffiti a way to get their art out there. Now with this commercial angle they are able to let people in to the world of street art and give them more of an understanding of where it comes from.

Legality and ethics

There is a gap that developed between the old graffiti era of the 70s and 80s and the newer alluring street art. It has also brought on a new value to the arts’ dollar’s worth and ensuing legal issues. There are legal complications and players include: the artist, the city or municipal government, the intended recipient, and the owner of the space such street art was displayed. The following is an example that occurred in 2014 in Bristol England and henceforth expounds on the legal, moral, and ethical questions that resulted. It revolved around a piece of street art called Mobile Lovers by a famous resident called Banksy. It was painted on plywood on a public doorway, then cut out by a citizen who in turn was going to sell the piece to garner funds for a Boys Club. The City government in turn confiscated the artwork and placed it in a museum. Banksy, hearing of the conundrum then bequeathed it to the original citizen, thinking his intentions were genuine. The complex controversy of ownership and public property as well as trespassing and vandalism are issues to be resolved legally.[32]

Street art, guerilla art, and graffiti

Graffiti is characteristically made up of written words that are meant to represent a group or community in a covert way and in plain sight. The tell tale sign of street art is that it usually includes images, illustrations, or symbols that are meant to convey a message.[5] While both works are meant to represent or tell a message to viewers, one difference between the two comes in the specific viewers that it is meant for. As stated earlier, graffiti displays a covert message in plain site by using terminology or messaging that is not made to be recognizable or understandable to viewers who are outside of the community or group for which it represents.[5] One trait of street art that has helped to bring it to positive light in the public eye is that the messages shown in these public spaces are usually made to be understandable to all.[5]

While both of these types of art have many differences, there are more similarities than their origins. Both graffiti and street art are works of art that are created with the same intent. Most artists, whether they are working anonymously, creating an intentionally incomprehensible message, or fighting for some greater cause are working with the same ambitions for popularity, recognition, and the public display or outpouring of their personal thoughts, feelings, and/or passions.[5]

The term street art is described in many different ways, one of which is the term "guerrilla art." Both terms describe these public works that are placed with meaning and intent. They can be done anonymously for works that are created to confront more taboo public issues that will result in backlash, or under the name of a well-known artist. In any case and terminology, these works of art are created as a primary way to express the artists thoughts on many topics and more commonly, public issues.[33]

One defining trait or feature of street art is that it is created on or in a public area without or against the permission of the owner.[34] This is a trait which falls in line with that of graffiti. A main distinction between the two comes in the second trait of street art or guerrilla art, where it is made to represent and display a purposefully uncompliant act that is meant to challenge its surrounding environment.[34] This challenge can be granular, focusing on issues within the community or broadly sweeping, addressing global issues on a public stage.

This is how the term "guerilla art" was associated with this type of work and behavior. The word ties back to guerilla warfare in history where attacks are made wildly, without control, and with no rules of engagement. This type of warfare was dramatically different than the previously formal and traditional fighting that went on in wars normally. When used in the context of street art, the term guerilla art is meant to give nod to the artist's uncontrolled, unexpected, and often unnamed attack on societal structure or norms.[35]

Guerilla sculpture

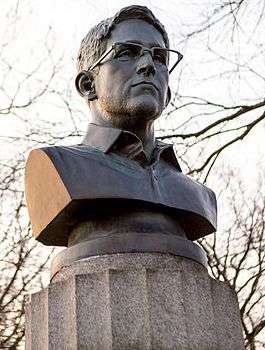

Guerilla sculpture is the placement of sculptures in street settings without official approval; it developed from street art in England in the late 20th century.[35] In addition to the nontraditional setting of the works of art involved, there are also many different techniques used in the creation of this art work. The artists tend to work illegally and in secrecy to create and place these works in the dark of night, cloaked in mystery regarding their origins and creators. The sculptures are used to express the artist's views and to reach audience groups that would not otherwise be reached through more traditional methods of displaying one's work to the public. In performing these acts of artistic expression, they are not working to gain acceptance or love of the people that they reach, but at times may even anger those who view their work.[35]

An example is the overnight appearance of an unsanctioned sculpture of Edward Snowden onto a column in Fort Greene Park in New York City.[35] In other cases the sculptures integrate two-dimensional backdrops with a three-dimensional component, such as one by Banksy titled Spy Booth (2014). The backdrop was painted on a wall in Cheltenham, England and featured Cold-War spy characters adorned in trench coats and fedoras, with spy accoutrements, microphones, and reel-to-reel tape decks. These characters appeared to be tapping into a broken telephone booth.[35]

A deviation from unsanctioned street sculpture is "institutionalized guerilla sculpture", which is sanctioned by civic authorities and can be commercialized. One such artist from the Netherlands is Florentijn Hofman, who in 2007 created Rubber Duck, a colossal rendition of the childhood tub-toy (2 by 20 by 32 metres (6 ft 7 in × 65 ft 7 in × 105 ft 0 in)). He calls it a "social response".

Public acceptance

Although this type of art has become a staple of most cities around the world, the popularity of this form of artistic expression was not always so apparent as it is today. In recent years, street art has undergone a major transformation in public opinion to even become a socially accepted and respected accent to the public places that they adorn.[34] Even with this push for public acceptance, the act of defacing public property with any and all message, whether it is considered art or not, has yet to become permitted or approved by the government.[34] Today's street art, while common and growing in acceptance, is largely placed in a middle ground between an act that is against the law and a beautifully respected act of artistic expression.

In the beginning, graffiti was the only form of street art that there was and it was widely considered to be a delinquent act of territorial marking and crude messaging. Initially, there was very clear devisions between the work of a street artist and the act of tagging a public or private property, but in recent years where the artists are treading the line between the two, this line has become increasingly blurred.[34] Those who truly appreciate the work of famed street artists or street works of art, are in acceptance of the fact that this art would not be the same without the medium being the street. The works are subject to whatever change or destruction may come due to the fact that they are created on public or private surfaces which are neither owned by the artist or permitted to be worked on by the property owners. This acceptance of the potential impermanence of the works of art and the public placement of the uncondoned works are what contribute to the meaning of the piece and therefore, what helps the growth of street art popularity.[34]

Around the globe

Street art exists worldwide. Large cities and regional towns of the world are home to some form of street art community, from which pioneering artists or forerunners of particular mediums or techniques emerge. Internationally known street artists travel between such locations to promote and exhibit their artwork.

North America

New York City attracts artists from around the world.[36] In Manhattan, "post-graffiti" street art grew in the 1980s from the then largely vacant neighborhoods of SoHo and the Lower East Side. The Chelsea art district became another locale, with area galleries also hosting formal exhibitions of street artist's work. In Brooklyn, the Williamsburg and Dumbo neighborhoods — especially near the waterfront — are recognized street art sites.[37]

Programs in the Pennsylvania cities of Philadelphia and Pittsburgh provide funding to agencies who employ street artists to decorate city walls. The Mural Arts Program established in 1984 has helped Philadelphia earn praise as the "City of Murals". The project was initiated to encourage graffiti artists toward a more constructive use of their talents. Murals backed by The Sprout Fund in Pittsburgh were named the "Best Public Art" by the Pittsburgh City Paper in 2006.[38][39]

Street art in Atlanta centers on the Old Fourth Ward and Reynoldstown neighborhoods, the Krog Street Tunnel, and along the 22-mile BeltLine railway corridor which circles the inner city. Atlanta established a Graffiti Task Force in 2011. Although the city selected a number of murals which would not be targeted by the task force, the selection process overlooked street art of the popular Krug Street Tunnel site. Art created in conjunction with the Living Walls street art conference, which Atlanta hosts annually, were spared. Some actions taken by the unit, including arrests of artists deemed vandals, caused community opposition; some considered the city's efforts as "misdirected" or "futile".[40][41]

Sarasota, Florida, hosts an annual street art event, the Sarasota Chalk Festival, founded in 2007. An independent offshoot known as Going Vertical sponsors works by street artists, but some have been removed as controversial.[42][43]

The Los Angeles neighborhood of Hollywood and streets such as Sunset Boulevard, La Brea, Beverly Boulevard, La Cienega, and Melrose Avenue are among key locations.[44] LAB ART Los Angeles, opened in 2011, devotes its 6,500 square feet of gallery space to street art. Artwork by locals such as Alec Monopoly, Annie Preece, Smear and Morley are among the collection.

San Francisco's Mission District is has densely packed street art along Mission Street, and along both Clarion and Balmy Alleys.[45] Streets of Hayes Valley, SoMa, Bayview-Hunters Point and the Tenderloin have also become known for street art.[46] San Diego's East Village, Little Italy, North Park, and South Park neighborhoods contain street artwork of VHILS, Shepard Fairey, MADSTEEZ, Space Invader, Os Gêmeos, among others. Murals by various Mexican artists can be seen at Chicano Park in the Barrio Logan neighborhood.

Montreal (Canada) has street art epicenters in Le Plateau-Mont-Royal, Villeray, Downtown Montreal Le Sud-Ouest, Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, and multiple art districts within the Island of Montreal.

Toronto (Canada) has a significant graffiti scene.[47]

Morley, Los Angeles (2010)

Morley, Los Angeles (2010) Barry McGee (Twist), LACMA parking garage (c.2005)

Barry McGee (Twist), LACMA parking garage (c.2005) Smear, Los Angeles (2006)

Smear, Los Angeles (2006)

South America

Buenos Aires has developed a reputation for its large scale murals and artworks in many subway stations and public spaces. The first graffiti artists started painting in street in the Argentine capital in the mid-1990s after visiting other countries in Europe and South America. One of the first recognized street artists in Argentina is Alfredo Segatori, nicknamed 'Pelado', who began painting in 1994 and holds the record for the longest mural in Argentina[48] measuring more than 2000m2.

São Paulo is also home to an internationally recognized street art scene.

An abundance of buildings slated for demolition provide blank canvases to a multitude of artists, and the authorities cannot keep up with removing artists output. "Population density" and "urban anxiety" are common motifs expressed by "Grafiteiros" in their street art and pichação, rune-like black graffiti, said to convey feelings of class conflict.

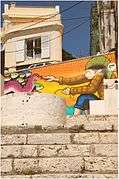

Influential Brazilian street artists include Claudio Ethos, Os Gêmeos, Vitche, Onesto, and Herbert Baglione.[49][50]

Work of Brazilian artists Os Gêmeos, in Lisbon, Portugal (2011)

Work of Brazilian artists Os Gêmeos, in Lisbon, Portugal (2011)

Europe

London has become one of the most pro-graffiti cities in the world. Although officially condemned and heavily enforced, street art has a huge following and in many ways is embraced by the public, for example, Stik's stick figures.[52] Dulwich Outdoor Gallery, in collaboration with Street Art London, is an outdoor "gallery" of street art in Dulwich, southeast London, with works based on traditional paintings in Dulwich Picture Gallery.[53]

Bristol has a prominent street art scene, due in part to the success of Banksy,[54] with many large and colourful murals dominating areas of the city.

Poland has artists like Sainer and Bezt known for painting huge murals on buildings and walls.[55]

Paris, France has an active street art scene which is home to artists such as Space Invader, Jef Aérosol, SP 38 and Zevs. Some connect the origins of street art in France to Lettrism of the 1940s and Situationist slogans painted on the walls of Paris starting in the late 1950s. Nouveau realists of the 1960s, including Jacques de la Villeglé, Yves Klein and Arman interacted with public spaces but, like pop art, kept the traditional studio-gallery relationship. The 1962 street installation Rideau de Fer (Iron Curtain) by Christo and Jeanne-Claude is cited as an early example of unsanctioned street art. In the 1970s, the site-specific work of Daniel Buren appeared in the Paris subway. Blek le Rat and the Figuration Libre movement became active in the 1980s.

Street art on the Berlin Wall was continuous during the time Germany was divided, but street art in Berlin continued to thrive even after reunification and is home to street artists such as Thierry Noir and SP 38. Post-communism, cheap rents, and ramshackle buildings gave rise to street art in areas such as Mitte, Prenzlauer Berg, Kreuzberg, and Friedrichshain.

The second biggest city in Estonia, Tartu, has been called the Estonian street art capital.[56] While Tallinn has been against graffiti, then Tartu is known for street art festival Stencibility and for being home for a wide range of works from various artist.[57]

The street art scene in Greece has been active since the late 1980s but gained momentum in Athens leading up to the country's 2011 financial crisis, with a number of artists raising voices of resistance, creating allegorical works and social commentary in the historic city center and Exarhia district. The New York Times published a story about the crisis in relation to street art, and art in general.[58] Street art by Bleeps.gr, whose work has been categorized as "artivism", can be found in neighborhoods such as Psiri.

Major Spanish coastal cities of Spain such as Barcelona, Valencia and Zaragoza have a vibrant street art scene.[59]

Italy has been very active in street art since the end of the 1990s; some of the most famous street artists include BLU, 108, and Sten Lex.

Street art in Amsterdam (Netherlands) centers on the Flevopark, on the east side, NDSM wharf in Amsterdam Noord, and the Red-light District. Artists who have gained recognition include Niels Shoe Meulman, Ottograph, Ives one, Max Zorn, Mickey, DHM, X Streets Collective,[60] Bustart, Mojofoto, Mark Chalmers and collective CFYE. The city is home to the "Amsterdam Street Art" group, promoting street art in the city with aims to bring it to the same level as that of London, Paris, and Barcelona.[61]

The city of Bergen is looked upon as the street art capital of Norway.[62] British street artist Banksy visited the city in 2000 and inspired many to take their art to the streets.[63] Dolk is among local street artists in Bergen.[64][65] His art can be seen around the city. Bergen's city council in 2009 chose to preserve one of Dolk's works with protective glass.[66]

In 2011, the city council launched a plan of action for street art from 2011–2015 to ensure that "Bergen will lead the fashion for street art as an expression both in Norway and Scandinavia".[67]

The city of Stavanger is host to the annual Nuart Festival, an event dedicated to promoting street art; the festival is one of the oldest curated "street art" festivals in the world. Nuart Plus is an associated industry and academic symposium dedicated to street art. The event takes place each September. Oslo, by contrast, has a zero tolerance policy against graffiti and street art, although artists such as DOT DOT DOT have created work there.

Street art came to Sweden in the 1990s and has since become the most popular way to establish art in public space. The 2007 book "Street Art Stockholm", by Benke Carlsson, documents street art in the country's capital.[68]

The street art scene of Finland had its growth spurt from the 1980s onwards, until in 1998 the city of Helsinki began a ten-year zero tolerance policy which made all forms of street art illegal, punishable with high fines, and enforced through private security contractors. The policy ended in 2008, after which legal walls and art collectives have been established.

Wheatpaste and stencil graffiti art in Denmark increased rapidly after visits from Faile, Banksy, Ben Eine, and Shepard Fairey between 2002–2004, especially in urban areas of Copenhagen such as Nørrebro and Vesterbro.[69] Copenhagen is home of TEJN, the artist credited with introducing the Lock On street art genre.

Since the collapse of communism in 1989, street art became prevalent in Poland throughout the 1990s. In the city of Łódź a permanent city exhibition was financed in 2011, under the patronage of Mayor Hanna Zdanowska, called "Urban Forms Gallery".[70] The exhibition included work from some of Poland's elite street artists as well as globally known artists. Despite being mostly accepted by the public, with authorities occasionally allowing artists licenses to decorate public places, other properties are still illegally targeted by artists. Warsaw and Gdańsk are other Polish cities with a vibrant street art culture.[71]

A monument in Bulgaria depicting Soviet Army soldiers was targeted by anonymous street artists in June, 2011. The soldiers of the monument, located in Sofia, were embellished to portray Ronald McDonald, Santa Claus, Superman, and others. The monument existed in that condition for several days before being cleaned. Some citizens were in favor of allowing the embellishments to remain.

Moscow has increasingly become a hub for Russian graffiti artists as well as international visitors. The Street Kit Gallery, opened in 2008, is dedicated to street art and organizes events in galleries, pop-up spaces and on the streets of the city. The 2009 Moscow International Biennale for Young Art included a section for street art. Active artists include Make, RUS, and Kiev-based Interesni Kazki (also active in Miami and Los Angeles).[72] Britain's BBC network highlighted the artwork of Moscow street artist Pavel 183 in 2012.[73][74]

The dissolution of the Soviet Union left Georgia with tantalizing urban space for the development of street art. Although it is a relatively new trend in Georgia, the popularity of street art is growing rapidly. Majority of Georgian street artists are concentrated in Tbilisi. Street art serves as a strong tool among the young artists to protest against the many controversial issues in the social and political life in Georgia and thus gets considerable attention in the society. Influential artists are Gagosh (street artist), TamOonz and Dr.Love.[74][75][76]

Street art by WATTTS in Paris

Street art by WATTTS in Paris Painting in the Global Tradition by Ces53, a Dutch street artist

Painting in the Global Tradition by Ces53, a Dutch street artist Street art in Sesimbra, Portugal

Street art in Sesimbra, Portugal- Graphic-Domain in Heidelberg by Nicola Pragera

Mural by BLU, Gaza Strip, Prague

Mural by BLU, Gaza Strip, Prague.jpg) Graffiti in Shoreditch, London by Stik

Graffiti in Shoreditch, London by Stik Urban art in Katowice, Poland

Urban art in Katowice, Poland

Asia

In South Korea's second largest city, Busan, German painter Hendrik Beikirch created a mural over 70 metres (230 ft) high, considered Asia’s tallest at the time of its creation in August, 2012. The monochromatic mural portrays fisherman.[77] It was organized by Public Delivery.[78]

A 2012 project in Malaysia funded by the Penang State Government was undertaken to liven up the streets and celebrate the recognition of Georgetown, Penang as a UNESCO site. Street art curated by Gabija Grusaite and drawn by Ernest Zacharevic were created on the walls of 18th-century terrace houses and the Clan Jetty located near Weld Quay (Pengkalan Weld). Initially done at the center of Chulia Street, near Khoo Kongsi, the increase in the number of visitors wishing to take pictures with the wall paintings has encouraged the government to support the street art culture. Steel rod sculptures have been added to the walls of buildings throughout Georgetown.

Oceania

Melbourne is home to one of the world's most active and diverse street art cultures and is home to pioneers in the stencil medium. Street artists such as Blek le Rat and Banksy often exhibited works on Melbourne's streets in the 2000s (decade). Works are supported and preserved by local councils. Key locations within the city include Brunswick, Carlton, Fitzroy, Northcote, and the city centre including the famous Hosier Lane.

Perth also has a small street art scene. Sydney's street art scene includes Newtown area graffiti and street art.

New Zealand: In 2009 in Auckland, street art decorated the city with sophisticated graphic imagery. Auckland's city council permitted electrical boxes to be used as canvases for street art. Local street art group TMD (The Most Dedicated) won the "Write For Gold" international competition in Germany two years in a row. Surplus Bargains is another local collective.[79]

Africa

Although street art in South Africa is not as ubiquitous as in European cities, Johannesburg's central Newtown district is a centre for street art in the city.[80] The "City Of Gold International Urban Art Festival" was held in the city's Braamfontein civic and student district in April 2012.[81]

The New York Times reported Cairo's emergence as a street art center of the region in 2011. Slogans calling for the overthrow of the Mubarak regime has evolved into æsthetic and politically provocative motifs.[82][83]

Street art from Egypt, Tunisia, Yemen, and Libya has gained notoriety since the Arab Spring, including a 2012 exhibition in Madrid' s Casa Árabe.[84]

Festivals and conferences

Sarasota Chalk Festival was founded in 2007 sponsoring street art by artists initially invited from throughout the US and soon extended to internationally. In 2011 the festival introduced a Going Vertical mural program and its Cellograph project to accompany the street drawings that also are created by renowned artists from around the world. Many international films have been produced by and about artists who have participated in the programs, their murals and street drawings, and special events at the festival.[85]

Living Walls is an annual street art conference founded in 2009.[86] In 2010 it was hosted in Atlanta and in 2011 jointly in Atlanta and Albany, New York. Living Walls was also active promoting street art at Art Basel Miami Beach 2011.[87]

The RVA Street Art Festival is a street art festival in Richmond, Virginia began in 2012. It is organized by Edward Trask and Jon Baliles. In 2012, the festival took place along the Canal Walk; in 2013 it was to take place at the abandoned GRTC lot on Cary Street.[88]

The Pasadena Chalk Festival, held annually in Pasadena, California, is the largest street-art festival in the world, according to Guinness World Records.[89] The 2010 edition involved about six hundred artists of all ages and skills and attracted more than 100,000 visitors.[90]

Documentary films

- Rash (2005), a feature-length documentary by Mutiny Media exploring the cultural value of Australian street art and graffiti

- Roadsworth: Crossing the Line (2007), a documentary film about the legal struggle of Montreal street artist Roadsworth

- Bomb It (2008), a documentary film about graffiti and street art around the world

- Eloquent Vandals (2011), a short documentary on the history of the Nuart Festival

- Exit Through the Gift Shop (2010), a documentary created by the artist Banksy about Thierry Guetta

- Street Art Awards (2010), opening of the street art festival in Berlin

- Las Calles Hablan (2013), Las Calles Hablan, a feature-length documentary about street art in Barcelona

- Style Wars (1983), a PBS documentary about graffiti artists in New York City featuring Seen, Kase2, Dez and DONDI

- DeeVaar, a documentary about graffiti and street art in Iran

See also

- Father Pat Noise

- Graffiti terminology

- Graffiti in Russia

- Graffiti in the United States

- Guerrilla marketing

- List of street artists

- Lock On street art

- Mustache Gallery, known for its experimental street art

- Mission School

- Public art

- Screen-printing

- Spray paint art

- Stencil

- Street art in Melbourne

- Street installation

- Street poster art

- Yarn bombing

References

- ↑ "Neo-graffiti" is a term coined by Tokion Magazine in the title of its Neo-Graffiti Project 2000, which featured "classic" subway graffiti artists working in new media; others have called this phenomenon "urban art." A discussion by the Wooster Collective on terminology can be found at WoosterCollective.com.

- 1 2 Schwartzman, Allan, Street Art, The Dial Press, Doubleday & Co., New York, NY 1985 ISBN 0-385-19950-3

- 1 2 3 Strausbaugh, John (5–11 April 1995). "Reneissance Man". New York Press. 8 (14). Manhattan, New York, US: Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr. p. Cover, 15, 16. ISSN 0362-4331. OCLC 1645522.

- ↑ Antonova, Maria. 2014. “Street Art.” Russian Life 57(5):17

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bloch, Stefano. 2015. “Street Art, Public City: Law, Crime and the Urban Imagination.” Urban Studies (Sage Publications, Ltd.) 52(13):2500-2503.

- ↑ Buzzell, Colby. "I am Banksy: a phantom with a stencil and a can of spray paint, maybe the premier 'guerrilla street artist' in the world, Banksy is almost impossible to find, but his work is everywhere and he makes people very, very happy." Esquire Dec. 2005: 198+. Academic OneFile. Web. 22 Apr. 2013.

- ↑ "Student art project is vandalism for a cause". The Herald-Times. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ For the development of style in the aerosol paint medium, as well as an examination of the political, cultural, and social commentary of its artists, see the anthropological history of New York subway graffiti art, Getting Up: Subway Graffiti in New York, by Craig Castleman, a student of Margaret Mead, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1982.

- ↑ Geek Graffiti: A Study in Computation, Gesture and Graffiti Analysis

- ↑ "Street art or street crime?". BBC. 14 September 2007.

- ↑ Acosta, Rocky (22 December 2011). "Street Art – Analog Free Culture".

- ↑ Lewisohn, Cedar (2008). Street Art: The Graffiti Revolution. New York: Abrams. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8109-8320-5.

- 1 2 Smith, Howard (21 December 1982). "Apple of Temptation". The Village Voice. Manhattan, New York, US. p. 38.

- ↑ Zotti, Ed (4 August 2000). "What's the origin of 'Kilroy was here'?". Straight Dope; staff report from the Science Advisory Board. Sun-Times Media, LLC. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ↑ Robinson, David (1990) Soho Walls – Beyond Graffiti, Thames & Hudson, NY, ISBN 978-0-500-27602-0

- ↑ Drasher, Katherine (1983-06-30). "Avant's on the Street". The Villager. pp. 31–32. Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- 1 2 Zox-Weaver, Annalisa (June 1, 2015). "Institutional Guerilla Art Open Access: The Public Sculpture of Florentijn Hofman". Sculpture Review. 3 (p 22-26).

- ↑ Tierney, John (6 November 1990). "A Wall in SoHo; Enter 2 Artists, Feuding". The New York Times. Manhattan, New York, US: Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr. ISSN 0362-4331. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ "Moncada v. Rubin-Spangle Gallery, Inc. – November 4, 1993.". Leagle.com. 4 November 1993. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ↑ Landes, William M.; Posner, Richard A. (2003). The Economic Structure of Intellectual Property Law (illustrated ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts, US: Harvard University Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-674-01204-2. OCLC 52208762. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ Ginsburgh, Victor; Throsby, C. D. (13 November 2006). Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture (illustrated, reprint ed.). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-444-50870-6. OCLC 774660408. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ Lerner, Ralph E.; Bresler, Judith (2005). Art law: the guide for collectors, investors, dealers, and artists (3rd ed.). New York City, New York, US: Practising Law Institute. ISBN 978-1-4024-0650-8. OCLC 62207673. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ Kostelanetz, Richard (2003). SoHo; The Rise and Fall of an Artist's Colony (1st ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 102–104. ISBN 0-415-96572-1. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ↑ Kahn, Steve (1999). SoHo New York. New York, NY: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc. p. 65. ISBN 0-8478-2156-0.

- ↑ I AM THE BEST ARTIST Rene mural (1987). The Secret of My Success (Comedy film). US: Universal Studios.

- ↑ Glassman, Carl (1985). SoHo; A Picture Portrait. New York, NY: Universe Books. pp. TK. ISBN 0-87663-566-4.

- 1 2 Lewisohn, Cedar (2008) Street Art: The Graffiti Revolution, Tate Gallery, London, England, ISBN 978-1-85437-767-8.

- ↑ "Incredible street art tours". Retrieved 2015-02-26.

- ↑ Means, Gary. "Alternative London Street Art Guides". alternativeldn.com. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ "Paris Underground". undergroundparis.org. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ "Alternative Berlin". alternativeberlin.com. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ Salib, Peter (Fall 2015). "The Law of Banksy: Who Owns Street Art?". University of Chicago Review. 82 (4 p293).

- ↑ Campos, Ricardo. 2015. “Youth, Graffiti, and the Aestheticization of Transgression.” Social Analysis 59(3):17-40.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bacharach, Sondra. 2015. “Street Art and Consent.” British Journal Of Aesthetics 55(4):481-495

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sisko (Summer 2015). "Guerilla Sculpture: Free Speech and Dissent". Sculpture Review. 64 (2): 26–35.

- ↑ Rojo, Jaime; Harrington, Steven P. (2010). Street Art New York. Prestel Pub. ISBN 978-3-7913-4428-7.

- ↑ Seth Kugel (9 March 2008) "To the Trained Eye, Museum Pieces Lurk Everywhere", The New York Times

- ↑ "History | Mural Arts Program". Muralarts.org. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ↑ Hoff, Al (14 December 2006). "Best Public Art: Sprout Fund Murals". Pittsburgh City Paper.

- ↑ Wheatley, Thomas (5 May 2011). "Atlanta's graffiti task force begins investigating, removing vandalism & Views | Creative Loafing Atlanta". Clatl.com. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ↑ Morris, Mike (4 October 2011). "Warrants issued for serial graffiti vandals". ajc.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ↑ Smith, Jessi, Get a ringside seat: MTO is not pulling any punches in his latest mural, This Week in Sarasota, 20 December 2012

- ↑ Rojo, Jamie and Harrington, Steven, "Unpremeditated" Movie from Street Artist MTO is a Knock Out, The Huffington Post, 20 March 2013

- ↑ Larson, Nicole (13 May 2011). "PHOTOS: Largest Street Art Collection Debuts At LAB ART LA". The Huffington Post.

- ↑ San Francisco Bay Guardian, 18–24 January 2012, p. 22

- ↑ Veltman, Chloe (8 May 2010) "Street Art Moves Onto Some New Streets", The New York Times

- ↑ "Toronto Graffiti :: urban artists for hire". Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ "Colorful mural might be world's longest | Reuters.com". mobile.reuters.com. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ↑ Romero, Simon (29 January 2012) "At War With São Paulo’s Establishment, Black Paint in Hand", The New York Times

- ↑ Scott, Gabe (17 July 2009). "Claudio Ethos". Exclusive Feature. High Speed Productions, Inc. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ↑ "The Banksy Paradox: 7 Sides to the World's Most Infamous Street Artist, 19 July 2007

- ↑ "Walking with Stik". Dulwich OnView, UK. 12 June 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ↑ Beazley, Ingrid (2015). Street Art, Fine Art. London: Heni Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9568738-5-9.

- ↑ "Has Banksy struck in Primrose Hill?". BBC News. 11 June 2010.

- ↑ "Huge murals on buildings created by artist duo ETAM CRU". NetDost. 16 January 2014.

- ↑ Karsten Kaminski. "Tänavakunst Tartus: rohkem kui ainult kunst" Postimees Kultuur, April 26, 2015 [in Estonian]

- ↑ Marika Agu & Sirla. Street art in Tartu, Estonia Vandalog, July 8th, 2014

- ↑ Donadio, Rachel (14 October 2011). "In Athens art blossoms amid debt crisis". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ↑ Street Art Website, Spain Section.. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ↑ "OTP's Guide to Street Art", Off Track Planet, 20 October 2011 (Archived Link)

- ↑ ''Amsterdam Street Art'' site. Amsterdamstreetart.com. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ↑ Ødegård, Ann Kristin (24 March 2010). "Gatekunstens hovedstad" (in Norwegian). Ba.no. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ↑ Thorkildsen, Joakim (10 March 2008). "Fikk Banksy-bilder som takk for overnatting" (in Norwegian). Dagbladet.no.

- ↑ "Derfor valgte ikke DOLK Bergen" (in Norwegian). Ba.no. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ↑ Bergesen, Guro H. "Populær Dolk selger så det suser" (in Norwegian). Bt.no. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ↑ "Forsvarer verning av graffiti" (in Norwegian). Ba.no. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

- ↑ "Bergenkommune.no – Graffiti og gatekunst i kulturbyen Bergen – Utredning og handlingsplan for perioden 2011–2015" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Bergen.kommune.no. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ↑ Carlsson, Benke (2007). Street art Stockholm. Stockholm: Ström. ISBN 9789171260765.

- ↑ Gallery housing mentioned street artists Archived 20 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Eugene (29 September 2011). "Polish City Embraces Street Art – My Modern Metropolis". Mymodernmet.com. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ↑ "Poland – Street-art and Graffiti". FatCap. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ↑ Alice Pfeiffer, "Graffiti Art Earns New Respect in Moscow", New York Times, 13 October 2010

- ↑ "Street artist 'Russia's answer to Bansky'". BBC. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- 1 2 Documentary film about street art in Tbilisi by KetevanVashagashvili."Gallery in the Street", 17 May 2015 Retrieved on 12 November 2015

- ↑ Caucasus Business Week www.cbw.ge "Amazing Street-Art of Georgia", 9 March 2015 Retrieved on 9 November 2015

- ↑ Georgia Today. Nina Ioseliani. www.georgiatoday.ge "Street art in Georgia", 20 August 2015 Retrieved on 27 August 2015

- ↑ Asia's Tallest Mural in South Korea by Hendrik Beikirch

- ↑ "Asia's tallest mural – By Hendrik Beikirch". Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ Allen, Linlee. (9 November 2009) Linlee Allen, "Street Smart | Auckland’s Art Bandits", The New York Times. Tmagazine.blogs.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ↑ "Report graffiti hotspots", City of Johannesburg site, 28 June 2012

- ↑ "South Africa: Hotel, Graffiti Crew Partner to Host Art Festival", AllAfrica.com, 16 April 2012. Allafrica.com (16 April 2012). Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ↑ Wood, Josh (27 July 2011) "The Maturing of Street Art in Cairo", The New York Times.

- ↑ "The Best Of Egyptian Political Street Art". Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ↑ Duggan, Grace. (2 February 2012) "Arab Spring Street Art, on View in Madrid", The New York Times.

- ↑ Chalk Festival, a forty-page guide to the 2012 Sarasota Chalk Festival, Sarasota Observer, 28 October through 6 November 2012

- ↑ Guzner, Sonia (22 August 2011). "'Living Walls' Speaks Out Through Street Art". The Emory Wheel. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ↑ "Living Walls". Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ "2013 RVA Street Art Festival to revitalize GRTC property". CBS6. 20 March 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ↑ Day, Brian (June 20, 2015). World's largest chalk art festival draws a crowd in Pasadena. Pasadena Star-News. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ↑ Day, Brian (June 20, 2010). Pasadena Chalk Festival called the world's largest street-art festival. Los Angeles Daily News. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

Further reading

- Avramidis, Konstantinos, & Tsilimpounidi, Myrto (Eds.), (2017), "Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City", Routledge, ISBN 978-1472473332

- Bearman, Joshuah (1 October 2008). "Street Cred: Why would Barack Obama invite a graffiti artist with a long rap sheet to launch a guerrilla marketing campaign on his behalf?". Modern Painters. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- Le Bijoutier (2008), This Means Nothing, Powerhouse Books, ISBN 978-1-57687-417-2

- Bou, Louis (2006), NYC BCN: Street Art Revolution, HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-06-121004-4

- Bou, Louis (2005), Street Art: Graffiti, stencils, stickers & logos, Instituto Monsa de ediciones, S.A., ISBN 978-84-96429-11-6

- Chaffee, Lyman (1993). Political Protest and Street Art: Popular Tools for Democratization in Hispanic Cultures. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-28808-9.

- Combs, Dave and Holly (2008), PEEL: The Art of the Sticker, Mark Batty Publisher, ISBN 0-9795546-0-8

- Danysz, Magda (2009) From Style Writing to Art, a street art anthology, Dokument Press, ISBN 978-8-888-49352-7

- Fairey, Shepard (2008), Obey: E Pluribus Venom: The Art of Shepard Fairey, Gingko Press, ISBN 978-1-58423-295-7

- Fairey, Shepard (2009), Obey: Supply & Demand, The Art of Shepard Fairey, Gingko Press, ISBN 978-1-58423-349-7

- Gavin, Francesca (2007), Street Renegades: New Underground Art, Laurence King Publishers, ISBN 978-1-85669-529-9

- Goldstein, Jerry (2008), Athens Street Art, Athens: Athens News, ISBN 978-960-89200-6-4

- Harrington, Steven P. and Rojo, Jaime (2008), Brooklyn Street Art, Prestel, ISBN 978-3-7913-3963-4

- Harrington, Steven P. and Rojo, Jaime (2010), Street Art New York, Prestel, ISBN 978-3-7913-4428-7

- Hundertmark, Christian (2005), The Art Of Rebellion: The World Of Street Art, Gingko Press, ISBN 978-1-58423-157-8

- Hundertmark, Christian (2006), The Art Of Rebellion 2: World of Urban Art Activism, Gingko Press, ISBN 978-3-9809909-4-3

- Jakob, Kai (2009), Street Art in Berlin, Jaron, ISBN 978-3-89773-596-5

- Longhi, Samantha (2007), Stencil History X, Association C215, ISBN 978-2-9525682-2-7

- Manco, Tristan (2002), Stencil Graffiti, Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-28342-7

- Manco, Tristan (2004), Street Logos, Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-28469-5

- Marziani, Gianluca (2009), Scala Mercalli: The Creative Earthquake of Italian Street Art, Drago Publishing, ISBN 978-88-88493-42-8

- Palmer, Rod (2008), Street Art Chile, Eight Books, ISBN 978-0-9554322-1-7

- Rasch, Carsten (2014), Street Art: From around the World – stencil graffiti – wheatpasted poster art – sticker art – Volume I, Hamburg, ISBN 978-3-73860-931-8

- Riggle, Nicholas Alden (2010), "Street Art: The Transfiguration of the Commonplaces," Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 68, Issue 3 (248–257).

- Robinson, David (1990) Soho Walls – Beyond Graffiti, Thames & Hudson, NY, ISBN 978-0-500-27602-0

- Ross, Jeffrey Ian (Ed.), (2016), "Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art", Routledge, ISBN 978-1138792937

- Schwartzman, Allan (1985), Street Art, The Dial Press, ISBN 978-0-385-19950-6

- Strike, Christian and Rose, Aaron (August 2005), Beautiful Losers: Contemporary Art and Street Culture, Distributed Art Publishers, ISBN 1-933045-30-2

- Walde, Claudia (2007), Sticker City: Paper Graffiti Art (Street Graphics / Street Art Series), Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-28668-5

- Walde, Claudia (2011), Street Fonts – Graffiti Alphabets From Around The World, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-51559-4

- Williams, Sarah Jaye, ed. (2008), Philosophy of Obey (Obey Giant): The Formative Years (1989–2008), Nerve Books UK.

External links

Media related to street art at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to street art at Wikimedia Commons- Street Art at DMOZ