Guard cell

Guard cells are specialized cells in the epidermis of leaves, stems and other organs that are used to control gas exchange.

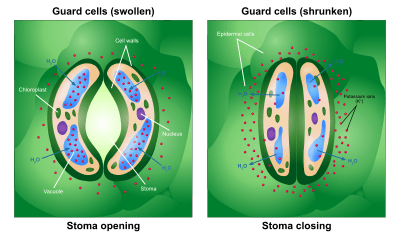

The guard cells are produced in pairs with a gap between them that forms a stomatal pore. The stomatal pores are largest when water is freely available and the guard cells turgid, and closed when water availability is critically low and the guard cells become flaccid. Photosynthesis depends on the diffusion of Carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air through the stomata into the mesophyll tissues. Oxygen (O2), produced as a byproduct of photosynthesis, exits the plant via the stomata. When the stomata are open, water is lost by evaporation and must be replaced via the transpiration stream, with water taken up by the roots. Plants must balance the amount of CO2 absorbed from the air with the water loss through the stomatal pores, and this is achieved by both active and passive control of guard cell turgor and stomatal pore size.[1][2][3][4]

Guard cell function

Opening and closure of the stomatal pore is mediated by changes in the turgor pressure of the two guard cells.The turgor pressure of guard cells is controlled by movements of large quantities of ions and sugars into and out of the guard cells. When guard cells take up these solutes, the water potential (Ψ) inside the cells increases(creating a hypertonic solution), causing osmotic water flow into the guard cells. This leads to a turgor pressure increase causing swelling of the guard cells and the stomatal pores open. The ions that are taken up by guard cells are mainly potassium (K+) ions[5][6][7] and chloride (Cl−) ions.[8] In addition guard cells take up sugars that also contribute to opening of the stomatal pores.

Water loss and water use efficiency

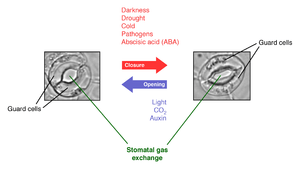

Water stress (drought and salt stress) is one of the major environmental problems causing severe losses in agriculture and in nature. Drought tolerance of plants is mediated by several mechanisms that work together, including stabilizing and protecting the plant from damage caused by desiccation and also controlling how much water plants lose through the stomatal pores during drought. A plant hormone, abscisic acid (ABA), is produced in response to drought. A major type of ABA receptor has been identified.[9][10] Future research is needed to test if these receptors can be used to engineer drought tolerance in plants. The plant hormone ABA causes the stomatal pores to close in response to drought, which reduces plant water loss via transpiration to the atmosphere and allows plants to avoid or slow down water loss during droughts. The use of drought tolerant crop plants would lead to a reduction in crop losses during droughts. Since guard cells control water loss of plants, the investigation on how stomatal opening and closure are regulated could lead to the development of plants with improved avoidance or slowing of desiccation and better water use efficiency.[1]

Ion uptake and release

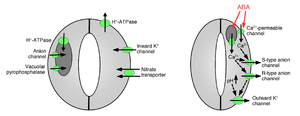

Ion uptake into guard cells causes stomatal opening: The opening of gas exchange pores requires the uptake of potassium ions into guard cells. Potassium channels and pumps have been identified and shown to function in the uptake of ions and opening of stomatal apertures.[7][11][12][13][14][15][16][17] Ion release from guard cells causes stomatal pore closing: Other ion channels have been identified that mediate release of ions from guard cells, which results in osmotic water efflux from guard cells due to osmosis, shrinking of the guard cells, and closing of stomatal pores (Figures 1 and 2). Specialized potassium efflux channels participate in mediating release of potassium from guard cells.[13][18][19][20][21] Anion channels were identified as important controllers of stomatal closing.[22][23][24][25][26][27][28] Anion channels have several major functions in controlling stomatal closing:[23] (a) They allow release of anions, such as chloride and malate from guard cells, which is needed for stomatal closing. (b) Anion channels are activated by signals that cause stomatal closing, for example by intracellular calcium and ABA.[23][26][29] The resulting release of negatively charged anions from guard cells results in an electrical shift of the membrane to more positive voltages (depolarization) at the intracellular surface of the guard cell plasma membrane. This electrical depolarization of guard cells leads to activation of the outward potassium channels and the release of potassium through these channels. At least two major types of anion channels have been characterized in the plasma membrane: S-type anion channels and R-type anion channels.[22][23][25][30]

Vacuolar ion transport

Vacuoles are large intracellular storage organelles in plants cells. In addition to the ion channels in the plasma membrane, vacuolar ion channels have important functions in regulation of stomatal opening and closure because vacuoles can occupy up to 90% of guard cell’s volume. Therefore, a majority of ions are released from vacuoles when stomata are closed.[31] Vacuolar K+ (VK) channels and fast vacuolar channels can mediate K+ release from vacuoles.[32][33][34] Vacuolar K+ (VK) channels are activated by elevation in the intracellular calcium concentration.[32] Another type of calcium-activated channel, is the slow vacuolar (SV) channel.[35] SV channels have been shown to function as cation channels that are permeable to Ca2+ ions,[32] but their exact functions are not yet known in plants.[36]

Signal transduction

Guard cells perceive and process environmental and endogenous stimuli such as light, humidity, CO2 concentration, temperature, drought, and plant hormones to trigger cellular responses resulting in stomatal opening or closure. These signal transduction pathways determine for example how quickly a plant will lose water during a drought period. Guard cells have become a model for single cell signaling. Using Arabidopsis thaliana, the investigation of signal processing in single guard cells has become open to the power of genetics.[26] Cytosolic and nuclear proteins and chemical messengers that function in stomatal movements have been identified that mediate the transduction of environmental signals thus controlling CO2 intake into plants and plant water loss.[1][2][3][4] Research on guard cell signal transduction mechanisms is producing an understanding of how plants can improve their response to drought stress by reducing plant water loss.[1][37][38] Guard cells also provide an excellent model for basic studies on how a cell integrates numerous kinds of input signals to produce a response (stomatal opening or closing). These responses require coordination of numerous cell biological processes in guard cells, including signal reception, ion channel and pump regulation, membrane trafficking, transcription, cytoskeletal rearrangements and more. A challenge for future research is to assign the functions of some of the identified proteins to these diverse cell biological processes.

Development

During the development of plant leaves, the specialized guard cells differentiate from “guard mother cells”.[39][40] The density of the stomatal pores in leaves is regulated by environmental signals, including increasing atmospheric CO2 concentration, which reduces the density of stomatal pores in the surface of leaves in many plant species by presently unknown mechanisms. The genetics of stomatal development can be directly studied by imaging of the leaf epidermis using a microscope. Several major control proteins that function in a pathway mediating the development of guard cells and the stomatal pores have been identified.[39][40]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Schroeder JI, Kwak JM, & Allen GJ (2001) Guard cell abscisic acid signalling and engineering drought hardiness in plants. Nature 410:327-330.

- 1 2 Hetherington AM & Woodward FI (2003) The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature 424:901-908.

- 1 2 Shimazaki K, Doi M, Assmann SM, & Kinoshita T (2007) Light regulation of stomatal movement. Annu Rev Plant Biol 58:219-247.

- 1 2 Kwak JM, Mäser P, & Schroeder JI (2008) The clickable guard cell, version II: Interactive model of guard cell signal transduction mechanisms and pathway. The Arabidopsis Book, eds Last R, Chang C, Graham I, Leyser O, McClung R, & Weinig C (American Society of Plant Biologists, Rockville), pp 1-17.

- ↑ Imamura S (1943) Untersuchungen uber den mechanismus der turgorschwankung der spaltoffnungs-schliesszellen. Jap. J. Bot. 12:251-346.

- ↑ Humble GD & Raschke K (1971) Stomatal opening quantitatively related to potassium transport. Evidence from electron probe analysis. Plant Physiol. 48:447-453.

- 1 2 Schroeder JI, Hedrich R, & Fernandez JM (1984) Potassium-selective single channels in guard cell protoplasts of Vicia faba. Nature 312:361-362.

- ↑ MacRobbie EAC (1981) Ion fluxes in 'isolated' guard cells of Commelina communis L. J. Exp. Bot. 32:535-562.

- ↑ Ma Y, Szostkiewicz I, Korte A, Moes D, Yang Y, Christmann A, & Grill E (2009) Regulators of PP2C phosphatase activity function as abscisic acid sensors. Science 324:1064-1068.

- ↑ Park SY, Fung P, Nishimura N, Jensen DR, Fujii H, Zhao Y, Lumba S, Santiago J, Rodrigues A, Chow TF, Alfred SE, Bonetta D, Finkelstein R, Provart NJ, Desveaux D, Rodriguez PL, McCourt P, Zhu JK, Schroeder JI, Volkman BF, & Cutler SR (2009) Abscisic acid inhibits type 2C protein phosphatases via the PYR/PYL family of START proteins. Science 324:1068-1071.

- ↑ Assmann SM, Simoncini L, & Schroeder JI (1985) Blue light activates electrogenic ion pumping in guard cell protoplasts of Vicia faba. Nature 318:285-287.

- ↑ Shimazaki K, Iino M, & Zeiger E (1986) Blue light-dependent proton extrusion by guard-cell protoplasts of Vicia faba. Nature 319:324-326.

- 1 2 Schroeder JI, Raschke K, & Neher E (1987) Voltage dependence of K+ channels in guard cell protoplasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:4108-4112.

- ↑ Blatt MR, Thiel G, & Trentham DR (1990) Reversible inactivation of K+ channels of Vicia stomatal guard cells following the photolysis of caged 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Nature 346:766-769.

- ↑ Thiel G, MacRobbie EAC, & Blatt MR (1992) Membrane transport in stomatal guard cells: The importance of voltage control. J. Memb. Biol. 126:1-18.

- ↑ Kwak JM, Murata Y, Baizabal-Aguirre VM, Merrill J, Wang M, Kemper A, Hawke SD, Tallman G, & Schroeder JI (2001) Dominant negative guard cell K+ channel mutants reduce inward-rectifying K+ currents and light-induced stomatal opening in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 127:473-485.

- ↑ Lebaudy A, Vavasseur A, Hosy E, Dreyer I, Leonhardt N, Thibaud JB, Very AA, Simonneau T, & Sentenac H (2008) Plant adaptation to fluctuating environment and biomass production are strongly dependent on guard cell potassium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105:5271-5276.

- ↑ Schroeder JI (1988) K+ transport properties of K+ channels in the plasma membrane of Vicia faba guard cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 92:667-683.

- ↑ Blatt MR & Armstrong F (1993) K+ channels of stomatal guard cells: Abscisic-acid-evoked control of the outward-rectifier mediated by cytoplasmic pH. Planta 191:330-341.

- ↑ Ache P, Becker D, Ivashikina N, Dietrich P, Roelfsema MR, & Hedrich R (2000) GORK, a delayed outward rectifier expressed in guard cells of Arabidopsis thaliana, is a K+-selective, K+-sensing ion channel. FEBS Lett 486:93-98.

- ↑ Hosy E, Vavasseur A, Mouline K, Dreyer I, Gaymard F, Poree F, Boucherez J, Lebaudy A, Bouchez D, Very AA, Simonneau T, Thibaud JB, & Sentenac H (2003) The Arabidopsis outward K+ channel GORK is involved in regulation of stomatal movements and plant transpiration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:5549-5554.

- 1 2 Keller BU, Hedrich R, & Raschke K (1989) Voltage-dependent anion channels in the plasma membrane of guard cells. Nature 341:450-453.

- 1 2 3 4 Schroeder JI & Hagiwara S (1989) Cytosolic calcium regulates ion channels in the plasma membrane of Vicia faba guard cells. Nature 338:427-430.

- ↑ Hedrich R, Busch H, & Raschke K (1990) Ca2+ and nucleotide dependent regulation of voltage dependent anion channels in the plasma membrane of guard cells. EMBO J. 9:3889-3892.

- 1 2 Schroeder JI & Keller BU (1992) Two types of anion channel currents in guard cells with distinct voltage regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:5025-5029.

- 1 2 3 Pei Z-M, Kuchitsu K, Ward JM, Schwarz M, & Schroeder JI (1997) Differential abscisic acid regulation of guard cell slow anion channels in Arabdiopsis wild-type and abi1 and abi2 mutants. Plant Cell 9:409-423.

- ↑ Negi J, Matsuda O, Nagasawa T, Oba Y, Takahashi H, Kawai-Yamada M, Uchimiya H, Hashimoto M, & Iba K (2008) CO2 regulator SLAC1 and its homologues are essential for anion homeostasis in plant cells. Nature 452:483-486.

- ↑ Vahisalu T, Kollist H, Wang YF, Nishimura N, Chan WY, Valerio G, Lamminmaki A, Brosche M, Moldau H, Desikan R, Schroeder JI, & Kangasjarvi J (2008) SLAC1 is required for plant guard cell S-type anion channel function in stomatal signalling. Nature 452:487-491.

- ↑ Grabov A, Leung J, Giraudat J, & Blatt MR (1997) Alteration of anion channel kinetics in wild-type and abi1-1 transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana guard cells by abscisic acid. Plant J. 12:203-213.

- ↑ Linder B & Raschke K (1992) A slow anion channel in guard cells, activation at large hyperpolarization, may be principal for stomatal closing. FEBS Lett. 131:27-30.

- ↑ MacRobbie EAC (1998) Signal transduction and ion channels in guard cells. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. London 1374:1475-1488.

- 1 2 3 Ward JM & Schroeder JI (1994) Calcium-activated K++ channels and calcium-induced calcium release by slow vacuolar ion channels in guard cell vacuoles implicated in the control of stomatal closure. Plant Cell 6:669-683.

- ↑ Allen GJ & Sanders D (1996) Control of ionic currents guard cell vacuoles by cytosolic and luminal calcium. Plant J. 10:1055-1069.

- ↑ Gobert A, Isayenkov S, Voelker C, Czempinski K, & Maathuis FJ (2007) The two-pore channel TPK1 gene encodes the vacuolar K+ conductance and plays a role in K+ homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:10726-10731.

- ↑ Hedrich R & Neher E (1987) Cytoplasmic calcium regulates voltage-dependent ion channels in plant vacuoles. Nature 329:833-836.

- ↑ Peiter E, Maathuis FJ, Mills LN, Knight H, Pelloux J, Hetherington AM, & Sanders D (2005) The vacuolar Ca2+-activated channel TPC1 regulates germination and stomatal movement. Nature 434(7031):404-408.

- ↑ Pei Z-M, Ghassemian M, Kwak CM, McCourt P, & Schroeder JI (1998) Role of farnesyltransferase in ABA regulation of guard cell anion channels and plant water loss. Science 282:287-290.

- ↑ Wang Y, Ying J, Kuzma M, Chalifoux M, Sample A, McArthur C, Uchacz T, Sarvas C, Wan J, Dennis DT, McCourt P, & Huang Y (2005) Molecular tailoring of farnesylation for plant drought tolerance and yield protection. Plant J 43:413-424.

- 1 2 Bergmann DC & Sack FD (2007) Stomatal development. Annu Rev Plant Biol 58:163-181.

- 1 2 Pillitteri LJ & Torii KU (2007) Breaking the silence: three bHLH proteins direct cell-fate decisions during stomatal development. Bioessays 29:861-870.