Global aphasia

| Global aphasia | |

|---|---|

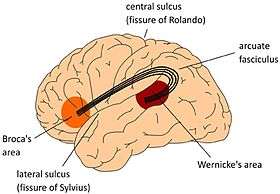

Global aphasia occurs due to a lesion in the perisylvian cortex, including Broca's and Wernike's areas.[1] |

Global aphasia, like all forms of aphasia, is a type of language disorder caused by damage to the brain.[1] Global aphasia is a severe form of nonfluent aphasia that affects both receptive and expressive language skills.[2] Severe, acquired impairments of communicative abilities are present across all language modalities, and often no single communicative modality is notably better than another.[3] Specifically, global aphasia leads to severe impairment of production, comprehension, and repetition of language.[1] Patients with global aphasia are unable to speak much; they may be able to say a few short utterances, but their overall production ability is very poor.[1] Furthermore, patients with global aphasia have an extremely impaired ability to understand what others say.[1] Lastly, those with global aphasia are almost fully incapable of repeating words and utterances.[1] This type of aphasia often results from a large lesion of the left perisylvian cortex[4] and is associated with damage to Broca's area, Wernicke's area, and insular regions which are associated with aspects of language.[5][6] Global aphasia profoundly impairs oral and written language production as well as auditory and written comprehension,[4] yet a person with global aphasia may still be able to express themselves through facial expressions, gestures and intonation.[3][7][8]

Signs and symptoms

The general signs and/or symptoms of global aphasia include the inability to comprehend speech, the inability to form speech, and the inability to repeat the speech one has heard.[1] Also, reading and writing are very difficult for individuals with global aphasia.[9] Global aphasia can be more severe in some patients than others; while one patient may not be able to speak at all, another patient may be able to make a few small utterances.[10] It is most common for the onset of global aphasia to occur after a stroke.[9]

Persons with global aphasia can neither read nor write, have poor word retrieval, repetition, and comprehension skills.[2] Additionally, auditory comprehension and speech are severely limited.[11] Persons with global aphasia are often mute or unable to say more than a few words or sounds, such as "hi" or "yes".[9] Performance of nonverbal tasks can range from satisfactory to normal.[2] However, it is possible for those affected by global aphasia to be able to express themselves using facial expressions, intonation, and gestures.[7] Most persons with global aphasia are unable to functionally read sentences and usually cannot even read simple words.[2] Extensive lexical impairment is also noted.[12] Global aphasia is usually accompanied by weakness of the right side of the face and right hemiplegia[11] but can occur with or without hemiparesis.[13] Additionally, it is common for an individual with global aphasia to have one or more of the following, additional impairments: apraxia of speech, alexia, pure word deafness, agraphia, facial apraxia, and depression.[10][14]

Persons with global aphasia are socially appropriate, usually attentive, and task-oriented.[2] Some are able to respond to yes/no questions, but responses are more reliable when questions refer to family and personal experiences.[2] Automatic speech is preserved with normal phonemic, phonetic and inflectional structures.[11] Right hemiparesis or hemiplegia, right-sided sensory loss, and right homonymous hemianopsia may manifest as well.[15] Persons with global aphasia may recognize location names and common objects’ names (single-words) while rejecting pseudo-words and real but incorrect names.[16]

Diagnosis

Global aphasia is diagnosed similarly to all forms of aphasia[10] A variety of testing is performed, where the language skills of a patient are tested.[10] The patient works alongside speech pathologists and a variety of other doctors to diagnose his or her condition.[10] Additionally, the Boston Assessment of Severe Aphasia (BASA) is a commonly used assessment for diagnosing aphasia.[10] BASA is used to determine treatment plans after strokes lead to symptoms of aphasia and tests both gestural and verbal responses.[17]

Causes

Global aphasia typically results from an occlusion to the trunk of the middle cerebral artery (MCA),[2] which affects a large portion of the perisylvian region of the left cortex.[4] The large areas in the anterior (Broca's) and posterior (Wernicke's) area of the brain are either destroyed or impaired because they are separate branches of the MCA that are supplied by its arterial trunk.[15] Lesions usually result in extensive damage to the language areas of the left hemisphere, however global aphasia can result from damage to smaller, subcortical regions.[15] In a study performed by Ferro (1992), it was found that five different brain lesion locations were linked to aphasia.[18] These locations include: "fronto-temporo-parietal lesions", "anterior, suprasylvian, frontal lesions", "large subcortical infarcts", "posterior, suprasylvian, parietal infarcts", and "a double lesion composed of a frontal and a temporal infarct".[18] Global aphasia is usually an effect of a thrombotic stroke rather than an embolic one.[15]

Prognosis

Persons with a large injury to the left perisylvian areas of the brain, often initially show signs of global aphasia in the first two days due to brain swelling (cerebral edema). With some recovery, impairment presentation may progress into expressive aphasia (most commonly) or receptive aphasia.[2][15] Due to the size and location of the lesion associated with global aphasia, the prognosis for language abilities is poor.[19] Research has shown that the prognosis of long-term language abilities is determined by the initial severity level of aphasia within the first four weeks after a stroke.[19] As a result, there is a poor prognosis for persons who retain a diagnosis of aphasia after one month due to limited initial language abilities.[2][4]

Although the prognosis for persons diagnosed with global aphasia is poor, minimal gains in language abilities are possible. For example, in 1992, Ferro performed research in which he studied the recovery of individuals with acute global aphasia, resulting from the five different lesion sites.[18] The first lesion site was in the fronto-tempo-parietal region of the brain; patients with lesions in this location had the poorest recovery of all the participants in the study, and they often never recovered from global aphasia at all.[18] However, the second lesion site was the anterior, suprasylvian, frontal part of the brain; the third lesion site was the subcortical infarcts; the fourth lesion site was the posterior, suprasylvian, parietal infarcts.[18] Participants with lesions two, three, and four often recovered to a less severe form of aphasia, such as Broca's or transcortical.[18] The fifth lesion site was a double lesion in both the frontal and temporal infarcts; patients with lesions at this site showed slight improvement.[18] However, studies show that spontaneous improvement, if it happens, occurs within six months but complete recovery is rare.[20]

Studies have shown persons with global aphasia have improved their verbal and nonverbal speech and language skills through speech and language therapy.[21][22] During therapy, most progress is seen within the first 3 years.[22] However, it is possible for language abilities to continuously improve at a steady rate due to long-term language intervention.[22] While improvement in language abilities is possible with intervention, only 20 percent of persons diagnosed with global aphasia achieve functional use of language.[2] Persons that do regain some functional language are typically limited to the communication of basic needs and the comprehension of simple conversations on highly familiar topics.[2]

Treatment

Research on the efficacy of treatment for global aphasia is somewhat inconclusive. Some studies have shown that persons diagnosed with global aphasia do not make significant gains. However, more recent studies have shown that speech and language therapy can be beneficial in improving functional communication and quality of life.[2][23] Global aphasia has been cited the most common type of aphasia in patients referred for speech therapy.[20][24] Outcomes of treatment are influenced by levels of motivation and other personality factors.[23] Speech and language goals for persons with global aphasia should be focused on improving participation in daily activities. Goals are chosen based on collaboration between speech-language pathologists, persons, and caregivers. Furthermore, goals are tailored to individual abilities and needs.[2] Examples include, a) providing persons with consistent "yes" and "no" responses to questions in structured situations, b) using simple gestures to represent basic wants and needs, c) writing words used in daily life, conveying basic communicative intentions, and d) comprehending simple directions.[15]

Therapy can be either group or individual. Group therapies integrating visual aids are good for persons with global aphasia because their social skills are largely intact.[15] Group therapy sessions typically revolve around simple, preplanned activities or games and aim to facilitate social communication.[15] Individual therapy sessions focus on improving communication essential for daily living. One particular therapy designed specifically for persons with aphasia is Visual Action Therapy (VAT).[8] VAT is a non-verbal gestural output program with 3 phases and 30 total steps.[25] The program teaches unilateral gestures as symbolic representations of real life objects. Research on the effectiveness of VAT is limited and inconclusive.[25] Another important therapy technique includes teaching family members and caregivers strategies for communicating with their loved one with global aphasia. Research offers such strategies including, a) simplifying sentences and using common words, b) gaining the person's attention before speaking, c) using pointing and visual cues, d) allowing for adequate response time, and e) creating a quiet environment free of distractions.[15] Additional forms of treatment can be broken down into the following categories: "language impairment-based treatment" and "activities/ participation-based treatment".[7] "Language impairment-based treatment" includes using computer programs to better language functioning, treatments centered on bettering one's reading ability, and treatments centered on bettering one's ability to retrieve words.[7] "Activities/participation-based treatment" often involves working with others to develop conversational skills.[7] Overall, treatment for persons with global aphasia can be effective and can improve patients' abilities to communicate and participate in daily life activities.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kemmerer, David. Cognitive Neuroscience of Language. New York: Psychology Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-84872-621-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Brookshire, R. H. (2007). Introduction to neurogenic communication disorders (Seventh edition.). St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby Elsevier.

- 1 2 Goodglass, H., and Kaplan, E. (1983). The assessment of aphasia and related disorders. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger.

- 1 2 3 4 Alexander, M.P. & Loverso, Felice. (1992). A specific treatment for global aphasia. Clinical Aphasiology, 21.

- ↑ Ozeren, A., Koc, F., Demirkiran, M., Sönmezler, A., & Kibar, M. (2006). Global aphasia due to left thalamic hemorrhage. Neurology India, 54(4), 415-417.

- ↑ Yourganov, G., Smith, K. G., Fridriksson, J., & Rorden, C. (2015). Predicting aphasia type from brain damage measured with structural MRI. Cortex, 73, 203-215.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Aphasia". American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- 1 2 Helm-Estabrooks, N., Fitzpatrick, P.M., Baressi, B. (1982). Visual action therapy for global aphasia. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 47, 385-389. doi:10.1044/jshd.4704.385

- 1 2 3 Mesulam, M (2010). "Aphasia, Sudden and Progressive". In Whitaker, Harry A. Concise Encyclopedia of Brain And Language (1 ed.). Elsevier Ltd. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-08-096498-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nichols, Clay; Nichols, Terri (1999). "GlobalAphasia". Global Aphasia Q & A. Stroke Information Directory. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 Damasio, A. R. (1992). Aphasia. New England Journal of Medicine, 326(8), 531-539.

- ↑ Bek, J., Blades, M., Siegal, M., & Varley, R. (2010). Language and spatial reorientation: Evidence from severe aphasia. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 36(3), 646-658. doi:10.1037/a0018281

- ↑ Pai A.R., Krishnan G, Prashanth S, Rao S. (2011). Global aphasia without hemiparesis: A case series. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2011;14:185–188

- ↑ Whitaker, H.A. (2007). "Language Disorders, Aphasia". In Whitaker, Harry A. Concise Encyclopedia of Brain And Language (1 ed.). Elsevier Ltd. pp. 274–275. ISBN 978-0-08-096498-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Collins, M., (1991). Diagnosis and Treatment of Global Aphasia. San Diego, CA: Singular Publishing Group, Inc.

- ↑ Wapner, W., & Gardner, H. (1979). A note on patterns of comprehension and recovery in global aphasia. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 22, 765-772.

- ↑ "Patterson Medical - BASA, Boston Assessment of Severe Aphasia". www.pattersonmedical.com. Retrieved 2015-12-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Christman, S. S.; Boutsen, F. R. (2006). "Recovery of Language after Stroke or Trauma in Adults". In Whitaker, Harry A. Concise Encyclopedia of Brain And Language (1 ed.). Elsevier Ltd. pp. 445–446. ISBN 978-0-08-096498-0.

- 1 2 Plowman, E., Hentz, B., & Ellis, C. (2012). Post-stroke aphasia prognosis: a review of patient-related and stroke-related factors. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18(3), 689-694. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01650

- 1 2 Prins, R; et al. (1978). "Recovery from aphasia: Spontaneous speech versus language comprehension". Brain Lang. 6: 192–211. doi:10.1016/0093-934X(78)90058-5. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ↑ Bakheit, A., Shaw, S., Carrington, S., & Griffiths, S. (2007). The rate and extent of improvement with therapy from the different types of aphasia in the first year after stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation, 21(10), 941-949

- 1 2 3 Smania, N., Gandolfi, M., Aglioti, S., Girardi, P., Fiaschi, A., & Girardi, F. (2010). How long is the recovery of global aphasia? Twenty-five years of follow-up in a patient with left hemisphere stroke. Neurorehabilitation & Neural Repair, 24(9), 871-875 5p. doi:10.1177/1545968310368962

- 1 2 Holland, A. L., & Fromm, D. S. (1996). Treatment efficacy: Aphasia. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research, 39(5), S27.

- ↑ Sarno, MT (1970). "A survey of 100 aphasic Medicare patients in a speech pathology program". J Am Geriatr Soc. 18: 471. doi:10.1016/0093-934X(81)90124-3. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- 1 2 Conlan, C.P. & Malcom, M.R. (1992). The efficacy of treatment for two globally aphasic adults using visual action therapy. Aphasiology, 185-195