Gideon v. Wainwright

| Gideon v. Wainwright | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Argued January 15, 1963 Decided March 18, 1963 | |||||||

| Full case name | Clarence E. Gideon v. Louie L. Wainwright, Corrections Director. | ||||||

| Citations |

83 S. Ct. 792; 9 L. Ed. 2d 799; 5951 U.S. LEXIS 1942; 23 Ohio Op. 2d 258; 93 A.L.R.2d 733; | ||||||

| Argument | Oral argument | ||||||

| Prior history | Defendant convicted, Bay County, Florida Circuit Court (1961); habeas petition denied w/o opinion, sub. nom. Gideon v. Cochrane, 135 So. 2d 746 (Fla. 1961) | ||||||

| Subsequent history | On remand, 153 So. 2d 299 (Fla. 1963); defendant acquitted, Bay County, Florida Circuit Court (1963) | ||||||

| Holding | |||||||

| The Sixth Amendment right to counsel is a fundamental right applied to the states via the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution's due process clause, and requires that indigent criminal defendants be provided counsel at trial. Supreme Court of Florida reversed. | |||||||

| Court membership | |||||||

| |||||||

| Case opinions | |||||||

| Majority | Black, joined by Warren, Brennan, Stewart, White, Goldberg | ||||||

| Concurrence | Clark | ||||||

| Concurrence | Harlan | ||||||

| Concurrence | Douglas | ||||||

| Laws applied | |||||||

| U.S. Const. amends. VI, XIV | |||||||

|

This case overturned a previous ruling or rulings | |||||||

| Betts v. Brady (1942) | |||||||

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963), is a landmark case in United States Supreme Court history. In it, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that states are required under the Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution to provide counsel in criminal cases to represent defendants who are unable to afford to pay their own attorneys. The case extended the right to counsel, which had been found under the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to impose requirements on the federal government, by ruling that this right imposed those requirements upon the states as well.

Facts and prior history

Between midnight and 8:00 a.m. on June 3, 1961, a burglary occurred at the Bay Harbor Pool Room in Panama City, Florida. An unknown person broke a door, smashed a cigarette machine and a record player, and stole money from a cash register. Later that day, a witness reported that he had seen Clarence Earl Gideon in the poolroom at around 5:30 that morning, leaving with a wine bottle and money in his pockets. Based on this accusation alone, the police arrested Gideon and charged him with breaking and entering with intent to commit petty larceny.

Gideon appeared in court alone as he was too poor to afford counsel, whereupon the following conversation took place:

The COURT: Mr. Gideon, I am sorry, but I cannot appoint counsel to represent you in this case. Under the laws of the State of Florida, the only time the court can appoint counsel to represent a defendant is when that person is charged with a capital offense. I am sorry, but I will have to deny your request to appoint counsel to defend you in this case.

GIDEON: The United States Supreme Court says I am entitled to be represented by counsel.

The Florida court declined to appoint counsel for Gideon. As a result, he was forced to act as his own counsel and conduct his own defense in court, emphasizing his innocence in the case. At the conclusion of the trial the jury returned a guilty verdict. The court sentenced Gideon to serve five years in the state prison.

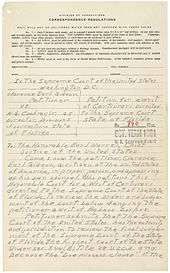

From the cell at Florida State Prison, making use of the prison library and writing in pencil on prison stationery,[1] Gideon appealed to the United States Supreme Court in a suit against the Secretary of the Florida Department of Corrections, H.G. Cochran. Cochran later retired and was replaced with Louie L. Wainwright before the case was heard by the Supreme Court. Gideon argued in his appeal that he had been denied counsel and, therefore, his Sixth Amendment rights, as applied to the states by the Fourteenth Amendment, had been violated.

The Supreme Court assigned Gideon a prominent Washington, D.C., attorney, future Supreme Court justice Abe Fortas of the law firm Arnold, Fortas & Porter. Opposing, Bruce Jacob, who later became Dean of the Mercer University School of Law and Dean of Stetson University College of Law, argued the case for the State of Florida.[2] Fortas was assisted by longtime Arnold, Fortas & Porter partner Abe Krash and famed legal scholar John Hart Ely, then a third-year student at Yale Law School.[3]

Court decision

The Supreme Court's decision was announced on March 18, 1963, and delivered by Justice Hugo Black. Three concurring opinions were written by Justices Clark, Douglas and Harlan. The Supreme Court decision specifically cited its previous ruling in Powell v. Alabama. Whether or not the decision in Powell v. Alabama applied to non-capital cases had sparked heated debate. Betts v. Brady had earlier held that, unless certain circumstances, such as illiteracy or stupidity of the defendant, or an especially complicated case, were present, there was no need for a court-appointed attorney in state court criminal proceedings. Betts had thus provided selective application of the Sixth Amendment right to counsel to the states, depending on the circumstances, as the Sixth Amendment had only been held binding in federal cases. Gideon v. Wainwright overruled Betts v. Brady, instead holding that the assistance of counsel, if desired by a defendant who could not afford to hire counsel, was a fundamental right under the United States Constitution, binding on the states, and essential for a fair trial and due process of law.

Justice Clark's concurring opinion stated that the Sixth Amendment to the Constitution does not distinguish between capital and non-capital cases, so legal counsel must be provided for an indigent defendant in all cases.[2] Justice Harlan's concurring opinion stated that the mere existence of a serious criminal charge in itself constituted special circumstances requiring the services of counsel at trial.

The Supreme Court remanded the case to the Supreme Court of Florida for "further action not inconsistent with this decision."

Gideon v. Wainwright was one of a series of Supreme Court decisions that confirmed the right of defendants in criminal proceedings, upon request, to have counsel appointed both during trial and on appeal. In the subsequent cases of Massiah v. United States, 377 U.S. 201 (1964) and Miranda v. Arizona 384 U.S. 436 (1966), the Supreme Court further extended the rule to apply even during police interrogation.

Implications

About 2000 individuals that had been convicted were freed in Florida alone as a result of the Gideon decision. The decision did not directly result in Gideon being freed; instead, he received a new trial with the appointment of defense counsel at the government's expense.

Gideon chose W. Fred Turner to be his lawyer in his second trial. The retrial took place on August 5, 1963, five months after the Supreme Court ruling. Turner, during the trial, picked apart the testimony of eyewitness Henry Cook, and in his opening and closing statements suggested that Cook likely had been a lookout for a group of young men who broke into the poolroom to steal beer, then grabbed the coins while they were at it. Turner also obtained a statement from the cab driver who had taken Gideon from Bay Harbor, Florida to a bar in Panama City, Florida, stating that Gideon was carrying neither wine, beer nor Coke when he picked him up, even though Cook testified that he had watched Gideon walk from the pool hall to the phone, and then wait for a cab. This testimony completely discredited Cook.

The jury acquitted Gideon after one hour of deliberation. After his acquittal, Gideon resumed his previous life and married again some time later. He died of cancer in Fort Lauderdale on January 18, 1972, at age 61. Gideon's family in Missouri accepted his body and laid him to rest in an unmarked grave. A granite headstone was added later.[4] It was inscribed with a quote from a letter Gideon wrote to Abe Fortas, the attorney appointed to represent him in the Supreme Court: "Each era finds an improvement in law for the benefit of mankind."[5]

Impact on courts

The former "incorrect trial" rule, where the government was given a fair amount of latitude in criminal proceedings as long as there were no "shocking departures from fair procedure" was discarded in favor of a firm set of "procedural guarantees" based on the Constitution. The court reversed Betts and adopted rules that did not require a case-by-case analysis, but instead established the requirement of appointed counsel as a matter of right, without a defendant's having to show "special circumstances" that justified the appointment of counsel.[4] In this way, the case helped to refine stare decisis: when a prior appellate court decision should be upheld and what standard should be applied to test a new case against case precedent to achieve acceptable practice and due process of law.[6] This confusion resulted in the implementation of several new practices by the Supreme Court when overturning a previous ruling to maintain the "impersonal qualities of the judicial process" and keep the sense that the legal system is without feeling or prejudice and simply applies justice to those who come before it.[7]

Public defender system

Many changes have been made in the prosecution and legal representation of indigent defendants since the Gideon decision. The decision created and then expanded the need for public defenders which had previously been rare. For example, immediately following the decision, Florida required public defenders in all of the state's circuit courts.[8] The need for more public defenders also led to a need to ensure that they were properly trained in criminal defense in order to allow defendants to receive as fair a trial as possible. Several states and counties followed suit. Washington D.C., for instance, has created a training program for their public defenders, who must receive rigorous training before they are allowed to represent defendants, and must continue their training in order to remain current in criminal law, procedure, and practices.[9] In 2010, a public defender's office in the South Bronx, The Bronx Defenders, created the Center for Holistic Defense, which has helped other public defender offices, from Montana to Massachusetts, developed a model of public defense called holistic defense or holistic advocacy. In it, criminal defense attorneys work on interdisciplinary teams, alongside civil attorneys, social workers, and legal advocates to help clients with not only direct but also collateral aspects of their criminal cases. More recently the American Bar Association and the National Legal Aid and Defender Association have set minimum training requirements, caseload levels, and experience requirements for defenders.[9] There is often controversy whether case loads set upon public defenders give them enough time to sufficiently defend their clients. Some criticize the mindset in which public defense lawyers encourage their clients to simply plead guilty. Some defenders say this is intended to lessen their own work load, while others would say it is intended to obtain a lighter sentence by negotiating a plea bargain as compared with going to trial and perhaps having a harsher sentence imposed. Tanya Greene, an ACLU lawyer, has said that is why 90 to 95 percent of defendants do plead guilty: "You've got so many cases, limited resources, and there's no relief. You go to work, you get more cases. You have to triage."[10]

Right to counsel

The Doughty v. Maxwell decision demonstrates the differences between how states and the federal government address standards for waiver of the right to counsel. In this case the Supreme Court granted certiorari and reversed the decision of the state court in Doughty, which held that regardless of Gideon, the defendant waived his or her right to appointed counsel by entering a plea of guilty. The underlying alleged crime and trial in Doughty took place in Ohio, which had its own way of interpreting the right to counsel as do many states. Pennsylvania and West Virginia also deemed that the right to counsel was waived when a plea of guilty was entered. Depending upon one's viewpoint, rules such as these could be seen as an attempt by a state to establish reasonable rules in criminal cases or as an attempt to save money even at the expense of denying a defendant due process. This varies a great deal from federal law, which generally has stricter guidelines for waiving the right to counsel. An analogous area of criminal law is the circumstances under which a criminal defendant can waive the right to trial. Under federal law, the defendant can only waive his or her right to trial if it is clear that the defendant understands the "charges, the consequences of the various pleas, and the availability of counsel".[11] State laws on the subject are often not as strict, making it easier for prosecutors to obtain a defendant's waiver of the right to trial.

See also

- Public defender

- Gideon's Trumpet, a book and TV movie based on this case

- Gideon's Army, a documentary film about public defenders in the American South

- List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 372

- Miranda warning

References

- ↑ "Petition for a Writ of Certiorari from Clarence Gideon to the Supreme Court of the United States, 01/05/1962". The National Archives. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- 1 2 "Clarence Earl Gideon, Petitioner, vs. Louis L. Wainwright, Director, Department of Corrections, Respondent". World Digital Library. 1963. Retrieved 2013-08-03.

- ↑ Krash, Abe (March 1998). "Architects of Gideon: Remembering Abe Fortas and Hugo Black". The Champion. NACDL. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- 1 2 Beaney, William M. (1963). "The Right to Counsel: Past, Present, and Future". Virginia Law Review. 49 (6): 1150–1159 [p. 1153]. doi:10.2307/1071050. JSTOR 1071050.

- ↑ King, Jack. "Clarence Earl Gideon: Unlikely World-Shaker". National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL). Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ Israel, Jerold H. (1963). "Gideon v. Wainwright: The 'Art' of Overruling". The Supreme Court Review. The University of Chicago Press. 1963: 211–272 [p. 218]. JSTOR 3108734.

- ↑ Israel (1963), p. 219.

- ↑ "Gideon's Promise, Still Unkept". The New York Times. 1993-03-18. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- 1 2 Abel, Laura. "2006 Edward v. Sparer Symposium: Civil Gideon: Creating a Constitutional Right to Counsel in the Civil Context: A Right to Counsel in Civil Cases: Lessons from Gideon v. Wainwright". Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review, Volume 15. Summer 2006.

- ↑ Daniel June "How Well are the Poor Publicly Defended?" (May 7, 2013)

- ↑ "Waiver of the Right to Counsel in State Court Cases: The Effect of Gideon v. Wainwright". University of Chicago Law Review. The University of Chicago Law Review. 31 (3): 591–602. 1964. doi:10.2307/1598554. JSTOR 1598554.

Further reading

- "Gideon's Promise Unfulfilled: The Need for Litigated Reform of Indigent Defense". Harvard Law Review. The Harvard Law Review Association. 113 (8): 2062–2079. 2000. doi:10.2307/1342319. JSTOR 1342319.

- Green, Bruce (June 2013). "Gideon's Amici: Why Do Prosecutors So Rarely Defend the Rights of the Accused?". Yale Law Journal. 122 (8): 2336–2357. The article describes how 23 state attorneys-general, led by Walter F. Mondale of Minnesota and Edward J. McCormack, Jr. of Massachusetts, when asked by Florida to participate as amici curiae, surprised the Florida Attorney General by submitting a "friend of the court" brief to the Supreme Court on the side of the accused, and advocating for the right to counsel of criminal defendants to defense counsel at the expense of the state.

- Uelmen, Gerald F. (1995). "2001: A Train Ride: A Guided Tour of the Sixth Amendment Right to Counsel". Law and Contemporary Problems. Duke University School of Law. 58 (1): 13–29. doi:10.2307/1192165. JSTOR 1192165.

- Van Alstyne, William W. (1965). "In Gideon's Wake: Harsher Penalties and the 'Successful' Criminal Appellant". Yale Law Journal. The Yale Law Journal Company, Inc. 74 (4): 606–639. doi:10.2307/794613. JSTOR 794613.

External links

-

Works related to Gideon v. Wainwright at Wikisource

Works related to Gideon v. Wainwright at Wikisource - Text of Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) is available from: Findlaw Justia LectLaw