Ganelon

In the Matter of France, Ganelon is the knight who betrayed Charlemagne's army to the Muslims, leading to the Battle of Roncevaux Pass. His name is said to derive from the Italian word inganno, meaning fraud or deception.[1] He is based upon the historical Wenilo, the archbishop of Sens who betrayed King Charles the Bald in 858.[2]

Appearances

Ganelon's most famous appearance is in The Song of Roland, where he is a well-respected Frankish baron, Roland's own stepfather and Charlemagne's brother-in-law. According to this chanson de geste Ganelon was married to Charlemagne's sister and had a son with her. He resents his stepson's boastfulness and great popularity among the Franks and success on the battlefield. When Roland nominates him for a highly dangerous mission (possibly even suicidally dangerous) as messenger to the Saracens, Ganelon is so deeply offended that he vows vengeance.

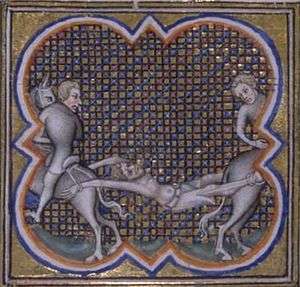

This vengeance becomes treachery as Ganelon plots with the pagan Blancandrin the ambush at Roncesvals. At the end, justice is served when Ganelon's comrade Pinabel is defeated in a trial by combat, showing that Ganelon is a traitor in the eyes of God. Thus Ganelon is torn limb from limb by four fiery horses.

In Canto XXXII of the Book of Inferno in Dante's The Divine Comedy, Ganelon (Ganellone) has been banished to Cocytus in the depths of hell as punishment for his betrayal.[1]

Ganelon (Italian: Gano; commonly: Gano di Pontieri, i.e. "Ganelon of Ponthieu"[1] or Gano di Maganza,[3] i.e. "Ganelon of Mainz".) also appears in Italian Renaissance epic poem romances dealing with Charlemagne, Roland (Italian: Orlando) and Renaud de Montauban (Italian: Renaldo or Rinaldo), such as Matteo Maria Boiardo's Orlando Innamorato and Luigi Pulci's Morgante.

In Don Quixote, Cervantes wrote, "To have a bout of kicking at that traitor of a Ganelon, he [Don Quixote] would have given his housekeeper, and his niece into the bargain."

He is also mentioned in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, both in "The Shipman's Tale", where his gruesome fate is a byeword (193-94: "... God take on me vengeance/ as foul as evere hadde Genylon of France") and in "The Nun's Priest's Tale" (225: "O false assassin, lurking in thy den! O new Iscariot, new Ganelon!").

The Account of Ganelon's treachery

Following is an account of Ganelon's crucial role in Charlemagne's willful ignorance, which brings about the death of Duke Benes of Aygremount, derived from the prose version chanson de geste and prose romance "Les Quatre Fils Aymon" (also known as "Renaud de Montauban") and translated to English by William Caxton as "The Right Pleasant and Goodly Historie of the Foure Sonnes of Aymon".[4]

Now, a little before the feast of St. John the Baptist, King Charlemagne held a great court in Paris, and Duke Benes did not forget to go there as he had promised. And so he departed from Aygremount with two hundred knights and took his way to Paris to serve the king, as he would have him do.

Now, the King being in Paris, his nephew the Earl Ganelon, Foulkes of Moryllon, Hardres, and Berenger, came to him and told him that Duke Benes was coming to serve him with two hundred knights, and Ganelon said: "Sire, how may you love or be well served by him who so cruelly has slain your son, our cousin? If it were your pleasure, we should well avenge you of him, for truly, we would slay him."

"Ganelon," said the king, "that would be treason, for we have given him our truce. But do as you will, so that the blame turn not upon me; and keep you well. For in certain the Duke of Aygremount is very powerful and of great kindred; and well might you find yourself with much to do, if you carry out your intent."

"Sire," said Ganelon, "care nothing for that. There is no man in all the world rich enough to undertake anything against me or my lineage. And Sire, tomorrow early we shall depart with 4,000 fighting men; and you may be sure we shall deliver the world of him."

"Certainly," said the king, "that would be treason."

"Care nothing for that," said Ganelon, "for he slew well your son Lohier by treason, and he was my kinsman; and therefore I will be avenged if I may."

"Now do as you will," said the king, "understanding always that I am not consenting thereto."

When morning came, Ganelon and his knights departed early from Paris, and with them full 4000 fighting men. And they rode without tarrying until they came to the Valley of Soissons; and there they encountered Duke Benes with his followers.

When Duke Benes saw them coming he said to his men, "Lords, I see that yonder are some people of the king's coming from the court."

"It is of no importance," said one of his knights.

"I know not what it may be," said the Duke, "for King Charlemagne is well able to think to avenge himself. And also he has with him a lineage of people who are deadly and cruel; that would be Ganelon, Foulkes of Moryllon, and certain others of his court. And in truth, last night I dreamed that a griffin came out of the heavens and pierced my shield and armor, so that his claws struck into my liver and my spleen. And all my men were in great torment and eaten by boars and lions, so that none escaped but one alone. And also, it seemed to me that out of my mouth issued a white dove."

Then one of his knights said that all was well, and he should not dismay himself because of the dream. "I know not what God shall send me," said the Duke, "but my heart dreads me for this dream."

Then Duke Benes commanded that every man should arm himself. And his knights answered that they would glady do so, and all sought their arms and equipment. And now you shall hear of the hard hewing and of a thing heavy to recount: the great slaughter that was made of the good Duke Benes of Aygremount, by the traitor Ganelon.

The text is online at:

https://archive.org/details/rightplesauntno4400caxtuoft

References

- 1 2 3 Boiardo, Orlando Innamorato, trans. Charles Stanley Ross, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995; I, i, 15, iv, p. 5 and note p. 399.

- ↑ J. L. Nelson, Charles the Bald (London: Longman, 1992), p. 188 n. 121.

- ↑ Pulci, Morgante, trans. Joseph Tusiani, notes by Edoardo A. Lèbano, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1998, p. 768 (note 8,3): "In the Italian tradition, all persons belonging to house of Maganza were considered potential traitors."

- ↑ Chapter 1, pp.51–53, a Modern English rendering published for The Early English Text Society by N. Trubner & Co., 1885.