Cultural Center of the Philippines

|

| |

| Government-owned corporation | |

| Founded | September 1966 |

| Headquarters | Manila, Philippines |

Key people |

Emily A. Abrera, Chairperson Raul Sunico, President Chris Millado, Vice President and Artistic Director |

| Products | Publications in Print and Multimedia |

| Services | Venue Rentals, Theatre Operations, Theater Rentals and Consultancy, Research, Building Tours, Information Services, Art Gallery |

| Owner | Government of the Philippines |

Number of employees | 300 (2011, Approx.)[1] |

| Website |

|

The Cultural Center of the Philippines (Filipino: Sentrong Pangkultura ng Pilipinas, or CCP) is a government owned and controlled corporation established to preserve, develop and promote arts and culture in the Philippines.[1][2] The CCP was established through Executive Order No. 30 s. 1966 by President Ferdinand Marcos. Although an independent corporation of the Philippine government, it receives an annual subsidy and is placed under the National Commission for Culture and the Arts for purposes of policy coordination.[1][3] The CCP is headed by an 11-member Board of Trustees, currently headed by Chairperson Emily Abrera. Its current president is Raul Sunico.

The CCP provides performance and exhibition venues for various local and international productions at its eponymous 62-hectare (150-acre) complex located in the Cities of Pasay and Manila. Its artistic programs include the production of performances, festivals, exhibitions, cultural research, outreach, preservation, and publication of materials on Philippine art and culture. It holds its headquarters at the Tanghalang Pambansa (English: National Theatre), a structure designed by National Artist for Architecture, Leandro V. Locsin. Locsin would later design many of the other buildings in the CCP Complex.[4]

History

"On the first year, I'll cover the soil. On the second year, I'll drive the pile. On the third year, the building will rise. On the fourth year, the curtain will rise"

Imelda Marcos to John Rockefeller III in 1966.

You do not develop culture by putting up a 50-million building on the bay...

Before the turn of the 20th century, artistic performances were primarily held in plazas and other public places around the country. In Manila, the Manila Grand Opera House, constructed in the mid-19th Century, served as the primary venue for many stage plays, operas and zarzuelas and other notable events of national significance.[7] Conditions improved with the construction of the Metropolitan Theater in 1931 and smaller but adequately equipped auditoriums in institutions like Meralco, Philam Life, Insular Life, Ateneo de Manila University and Far Eastern University. In 1961, the Philippine-American Cultural Foundation started to raise funds for a new theater. The structure, designed by Leandro Locsin, was to be built on a 10-hectare (25-acre) lot in Quezon City. In the meantime in 1965, Imelda Marcos at a proclamation rally in Cebu for her husband's bid for the Presidency, expressed her desire to build a national theater. Marcos would win his election bid and work on the theater started with the issuance of Presidential Proclamation No. 20 on March 12, 1966.[5] Imelda, now the First Lady, persuaded the Philippine-American Cultural Foundation to relocate and expand plans for the still-born theater to a new reclaimed location along Roxas Boulevard in Manila. To formalize the project, President Marcos issued Executive Order No. 60, establishing the Cultural Center of the Philippines and appointing its board of directors. The board would elect Imelda as chairperson, giving her the legal mandate to negotiate and manage funds for the center.[6][8]

Prior to her husband's inaugural, Marcos already started fund raising for the Cultural Center; an initial half-a-million Pesos was made from the proceeds of the premiere of Flower Drum Song in the University of the Philippines, and another ninety-thousand Pesos turned over from the Filipino arm of the Philippine-American Cultural Foundation. This was however, insufficient to cover the projected cost of PH₱15 million needed to construct the theater. Much of the theater's funding came from a war damage fund for education authorized by the US Congress during President Marcos's state visit to the United States. In the end, the theater would receive US$3.5 million from the fund. To make up for the rest of the construction costs, Imelda approached prominent families and businesses to donate to her cause. Carpets, draperies, marble, artworks to decorate the interior of the theater and even cement were all donated. Despite the success of the First Lady's fund raising, the project cost ballooned to almost ₱50 million, or 35 million over the projected budget by 1969. Imelda and the CCP board took a US$7 million loan through the National Investment Development Corporation to finance the remaining amount, a move that was heavily criticized by government opposition. Senator Ninoy Aquino strongly objected to the use of public funds for the center without congressional appropriation and branded it as an institution for the elite.[6] Unfazed with the criticism, Marcos went ahead with the project and the Theater of Performing Arts (Now the Tanghalang Pambansa) of the Cultural Center of the Philippines was opened on September 8, 1969, three days before the President's 52nd birthday, with a three-month-long inaugural festival opened by Lamberto Avellana's musical Golden Salakot: Isang Dularawan, an epic portrayal of Panay Island. Among those who attended the inaugural night were California Governor Ronald Reagan and his wife, Nancy, both representing United States President Richard Nixon.[9]

Early into the 1970s, the Center was in the red mainly due to the costs of constructing the Theater of Performing Arts. In 1972, the board of the CCP asked Members of Congress to pass House Bill 4454, which would convert the Center to become a non-municipal public corporation and allow it to use the principal of the CCP Trust Fund to pay off some of its debt. The bill would also continually support the center through a government subsidy amounting to the equivalent of 5% of the collected Amusement Tax annually. The proposed piece of legislation was met with strong opposition, and was never passed. However, with the declaration of Martial Law on September 23, 1972, Congress was effectively dissolved; and President Marcos signed Proclamation No. 15 s. 1972, essentially a modified version of the proposed bill. The proclamation also expanded the Center's role, from that of being a performance venue to an agency promoting and developing arts and culture throughout the country.[2] Other notable developments during the year included the institution of the National Artist Awards and the foundation of the CCP Philharmonic Orchestra, the center's first resident company that would later become the Philippine Philharmonic Orchestra.[5]

During this period of the Marcos Presidency, the CCP Complex played host to major local and international events under the guise of the Bagong Lipunan (New Society), which would mark the start of a series of major construction projects in the area. When Filipino Margie Moran won the 1973 Miss Universe Pageant, the Philippine Government agreed to stage the succeeding year's contest, and plans for an amphitheater commenced. Weeks of planning and discussions resulted to the commissioning of the Folk Arts Theater (Now the Tanghalang Francisco Balagtas), an open-air but roofed structure that could seat up to 10,000 people. Construction of the new theater, which was also designed by Leandro Locsin, was completed in a record 77 days and was inaugurated on July 1972 with the grand parade, "Kasaysayan ng Lahi" ("History of the Race").[6][10] Right after the inauguration of Folk Arts, ground was broken for the Philippine International Convention Center and the Philippine Plaza Hotel, both for the country's hosting of the IMF-World Bank Annual Meeting in 1976. Although not owned by the Cultural Center, these buildings were nevertheless built at the complex and designed by Locsin. One of the more infamous additions to the Center was the Manila Film Center, built in 1981 for the Manila International Film Festival. Designed by Froilan Hong, the structure was built on a strict critical path schedule requiring 4,000 workers working in 3 shifts across 24 hours. An accident occurred on November 17, 1981, when scaffolding collapsed and sent construction workers into quick-drying cement. Despite this, construction proceeded, and finished some 15 minutes before opening night of the Film Festival.[6] The building's ownership would be transferred to the CCP in 1986, when the Experimental Cinema of the Philippines was dissolved.[5] Straying from the brutalist style typical of the buildings in the CCP is the Coconut Palace, a showcase on the versatility of coconut as an export product and construction material, designed by Francisco Mañosa. The financial and human costs of constructing these buildings, in a time of widespread poverty and corruption, was seen as symptomatic of the First Lady's edifice complex, a charge Imelda has nevertheless welcomed in her later years.[6][11]

1986 saw the end of the Marcos regime through the peaceful People Power Revolution. Consequently, the CCP underwent a period of reform and "Filipinization". President Corazon Aquino appointed Maria Teresa Roxas as the first President of the Cultural Center in the post-Marcos era; and once critic of the center for its promotion of elitist culture, Nicanor Tiongson, accepted the position to be the new artistic director. Together with its vice president, Florendo Garcia, the new leadership consulted with various stakeholders to formulate a new direction for the CCP and officially redefine its mission and objectives in pursuit of "a Filipino national culture evolving with and for the people".[12] To set about decentralization, the Center formulates guidelines for setting-up local arts councils in local government units and establishes the CCP Exchange Artist Program to provide opportunities for regional groups to showcase their talents across the country. For the first time in her presidency, Aquino visited the center on January 11, 1987 to confer the National Artist Award to Atang de la Rama, marking the first time the awards were conferred through a process of democratic selection in addition to rigid criteria.[12] Aquino would later confer the same award to Leandro Locsin in 1990, in recognition of his contribution to the field of architecture in the Philippines and in spite of his many contributions to the Marcos regime's architectural projects. Also in 1987, three groups joined the roster of the Cultural Center's resident companies: the Philippine Ballet Theatre, the Ramon Obusan Folkloric Group and Tanghalang Pilipino.[5] As part of its outreach and research programs, the CCP produced a number of notable publications, including: Ani (English: Harvest) (1987), an arts journal; the Tuklas Sining (English: Discover Arts) (1989) series of monographs and videos on Philippine arts and the landmark 10-volume CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art (1994).[12][13] Despite its attempt at reforms, some people still see the center in a less positive light. For instance, former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo said that she finds the CCP to be "imposing, unapproachable, and elitist" for Filipino masses.[14]

Events and programs

The scope of activities the center engages in include architecture, film and broadcast arts, dance, literature, music, new media, theatre and visual arts. Aside from the its promotion of local and indigenous artists, it has played host to numerous prominent and international artists like Van Cliburn, Plácido Domingo, Marcel Marceau, the Bolshoi Ballet, the Kirov Ballet, the Royal Ballet, the Royal Danish Ballet, the New York Philharmonic, and the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra among many others.

From 1972, the CCP administered the Order of the National Artists, which is the highest recognition the government of the Philippines gives to individuals who made significant contributions to the development of arts in the country. The Order was established in 1972 after the death of renowned painter Fernando Amorsolo, through the auspices of Proclamation No. 1001.[15] A year later, the Board of Trustees of the Center was designated as the National Artists Award Committee.[16] Today, the CCP administers the Order in conjunction with the National Commission for Culture and the Arts.

Since its reform for democratization in 1986, the center has undertaken steps to bring culture and arts more accessible to a larger segment of the Filipino society. Its Outreach Program conducts fora and art appreciation activities in various parts of the country, which includes the Sopas, Sining at Sorbetes Program (English: Food to Taste, Arts to Appreciate. Literally, Soup, Art and Ice Cream), a unique appreciation activity coupled with a feeding program for underprivileged youth.[17] Every year since 2005, the center organizes its open house festival, Pasinaya (English: To Show. Literally, Debut or Inauguration) during February, designated as the National Arts Month in the Philippines. The Pasinaya festival features performing arts group from all over the country, led by the center's resident companies, in a one-day showcase of local talent entirely held in the Tanghalang Pambansa's numerous venues. In 2007 alone, the festival was visited by some 10,000 people.[18] The CCP also provides institutional support to the Cinemalaya Philippine Independent Film Festival and the Philippine High School for the Arts.

Resident companies

Management

The President and Chief Operating Officer is Raul Sunico, while Chris Millado is Vice President and Artistic Director.[19] The Board of Trustees is chaired by Emily Abrera. The other Board members are:[20]

|

|

Advisers

- Baltazar N. Endriga

- Nestor O. Jardin

Presidents of the CCP[21]

| President | Term office | Ruling President |

|---|---|---|

| Jaime Zobel de Ayala | 1969-1976 | Ferdinand Marcos |

| Lucrecia Kasilag | 1976-1986 | |

| Ma. Teresa Roxas | 1986-1994 | Corazon Aquino |

| Fidel Ramos | ||

| Francisco del Rosario, Jr. | 1994-1995 | |

| Baltazar Endriga | 1995-1999 | |

| Armina Rufino | 1999-2001 | Joseph Estrada |

| Nestor Jardin | 2001-2009 | Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo |

| Isabel Caro Wilson | 2009-2010 | |

| Raul M. Sunico | 2010-present | Benigno Aquino III |

Complex

The CCP Complex is an 88-hectare (220-acre) reclaimed property along Roxas Boulevard, most of which fall under the jurisdiction of the City of Pasay.[note 1] It is part of Bay City (formerly Boulevard 2000) that spans 1,500 hectares (3,700 acres) of reclaimed land along Manila Bay.[22] The Cultural Center owns 77 hectares (190 acres) of the land, with the rest being occupied by the Government Service Insurance System, the SM central business park, and PAGCOR's Entertainment City, among others. Development of the complex was stalled until 2000, when the Philippine Supreme Court ruled with finality the Center's ownership of some 35 hectares (86 acres) of prime real estate in the complex.

Facilities and performance venues

Tanghalang Pambansa

| Theater of Performing Arts | |

| |

.svg.png) Tanghalang Pambansa (National Theater) Location | |

| Address |

Cultural Center of the Philippines, Roxas Boulevard Manila Philippines |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 14°33′24″N 120°58′51″E / 14.556667°N 120.980833°E |

| Operator | Cultural Center of the Philippines |

| Type | National |

| Capacity |

Main Theater - 1,853 Little Theater - 421 Studio Theater - 240 Film Theater - 100 |

| Construction | |

| Opened | September 8, 1969 |

| Architect | Leandro V. Locsin |

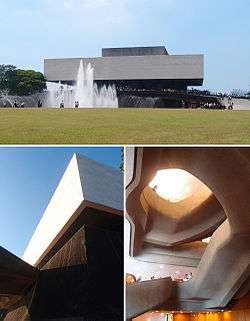

The Tanghalang Pambansa (English: National Theater), formerly, Theater of Performing Arts, is the flagship venue and principal offices of the Center. Designed by National Artist for Architecture Leandro Locsin, its design was based and expanded upon the unconstructed Philippine-American Friendship Center. The Tangahalan is a primary example of the architect's signature style known as the floating volume, a trait can be seen in structures indigenous to the Philippines such as the nipa hut. It houses three performing arts venues, one theater for film screenings, galleries, a museum and the center's library and archives. Being a work of a National Artist, the brutalist structure is qualified to be an important cultural landmark as stipulated in Republic Act No. 10066.[23]

Construction began in 1966, with Alfredo Juinio serving as structural engineer and Filipino firm DM Consunji as builder. Originally called the Theater of Performing Arts, it was completed and inaugurated in 1969. Its first major renovation occurred in 2005 for the opening and closing ceremonies of the 112th General Assembly of the Inter-Parliamentary Union held in Manila. Included in the renovation were cleaning and replacement of the marble trim, installation of a new air-conditioning system and new carpeting.[24]

Architecture

The façade of the National Theater is dominated by a two-storey travertine block suspended 12 meters (39 ft) high by deep concave cantilevers on three sides. The rest of the structure is clad in concrete, textured by crushed seashells originally found on the reclamation site.[6] The building is built on a massive podium, and entry is through a vehicular ramp in front of the raised lobby and a pedestrian side entry on its northwest side. In front of the façade and below the ramp, there is an octagonal reflecting pool with fountains and underwater lights. On the main lobby, three large Capiz-shell chandeliers hang from the third floor ceiling, each symbolizing the three main geographical divisions of the Philippines: Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao. At the orchestra entrance, a brass sculpture, The Seven Arts by Vicente Manansala welcomes the audience into the main theater. From the pedestrian entrance, Arturo Luz's Black and White is displayed as spectators enter the little theater or ascend to the main lobby through a massive carpeted spiral staircase. Most of the interior is lit artificially, as there are few windows, most of which are located along the sides of the main lobby. Large areas on the upper floors are open to the ground floor lobby, emphasizing the large chandeliers and fluid interior spaces on northeast side of the building. Galleries and other rooms surround these open areas, occupying the space created by the huge cantilevered block. Whenever possible, the walls surrounding these rooms are used as additional venues for displaying art works.

Much of the criticism of the building's architecture is directed towards its vehicular ramp. Since there are usually no valet services or parking areas directly accessible from the lobby entrance, the ramp's use is ideal only for audience members who are chauffeur-driven; at the expense of pedestrians, who may enter through the side entrance or a narrow (and potentially hazardous) pathway on the ramp.[25][26] In defense of the design, Andy Locsin (a partner of his father's firm) explained that the decision of raising the whole structure on the podium (and consequently, the addition of the ramp) was in response to the high sea levels on the reclaimed land, and was not intended to promote an elitist view of art and culture.[8]

Venues

The Tanghalang Nicanor Abelardo or the Main Theater is the largest performance venue inside the Tanghalang Pambansa. It can accommodate up to 1,815 people in four levels: Orchestra, Boxes and two Balconies. The stage is 25 meters (82 ft) from the main curtain line to the back wall and 38.8 meters (127 ft) from the left wall to the right. The proscenium opening has a height of 9 meters (30 ft) and width of 18 meters (59 ft). A 5.6388-meter (18 ft 6 in) deep orchestra pit contains two elevators that can accommodate up to 62 musicians. The stage floor, unwaxed and painted matte-black (originally not stained), is made from a species of Philippine Mahogany.[27] The main stage curtain is patterned after the painting Genesis, a work of National Artist Hernando Ocampo. A variable acoustics hall designed by Bolt, Beranek and Newman, the Main Theater was planned for flexibility. It was built to accommodate sound requirements of various types of presentations, and can typically hold opera and orchestra performances without further amplification.[28] New York Times critic Howard Taubman praised the theater's acoustical flexibility in his review of the center's opening night, writing that the architect and his team seem to have built a venue "that will be equally congenial for drama, instrumental and vocal music and dance."[29]

The Tanghalang Aurelio Tolentino or the Little Theater, inaugurated a few years after the opening of the CCP, is a conventional proscenium stage, designed for drama, chamber music, solo recitals, lectures, and film screenings. It seats 413 people in one orchestra section. From the main curtain line to the back wall, the stage measures 13.6 meters (45 ft) with a proscenium width of 13.9192 meters (45 ft 8 in) and features the same Mahogany flooring as the larger Main Theater. A covered orchestra pit extends into the apron gives additional performance space, similar to a thrust stage.[30] The stage curtain is a tapestry woven in Kyoto, Japan, based on a painting of Roberto Chabet, visual artist and former director of the CCP Museum. When unfolded, the curtain acts as a natural sound reverberation medium.

The Center has a lone black box theater named Tanghalang Huseng Batute or the Studio Theater, after the pseudonym of Filipino poet José Corazón de Jesús. Depending on the size of the stage or acting area, it can seat up to 240 people in two levels. The 100-seat Tanghalang Manuel Conde or the Dream Theater, a joint project of the CCP and Dream Broadcasting, is used as a venue for film screenings and lectures; and has the capability to receive and show films directly through satellite.

Exhibit halls

The Tanghalang Pambansa has three exhibit halls and another three hallways that can be used for displaying artwork. The largest exhibition space is the Bulwagang Juan Luna, which serves as the Main Gallery. Located on the third floor, it has a floor area of 440 square meters (4,700 sq ft). Two smaller galleries are named after Filipino painters Fernando Amorsolo and Carlos Francisco. The latter is usually used for large scale installations and is located at the lobby of the Little Theater. Hallways lining the Main Theater on the upper three storeys are also used for display and measure 2.4 meters (7 ft 10 in) high by 30.2 meters (99 ft) wide each. These spaces are named after visual artists Victorio Edades, Guillermo Tolentino and Vicente Manansala.

Established in 1988 the Museo ng Kalinangang Pilipino, also the CCP Museum, is an integrated humanities museum that studies, collects and preserves Filipino artistic traditions. It has two permanent exhibitions: one on Filipino tradition, art and aesthetics; and the other showcasing the Center's collection of traditional Asian musical instruments. The museum also presents special changing exhibitions, provides curatorial assistance, and organizes workshops on indigenous art forms.

Tanghalang Fransisco Balagtas

| Folk Arts Theater | |

| Address |

Cultural Center of the Philippines, Roxas Boulevard Pasay Philippines |

|---|---|

The Tanghalang Francisco Balagtas, more commonly known by its original name of Folk Arts Theater, is a covered proscenium amphitheater is where popular concerts are usually staged. It has a seating capacity of 8,458 in ten sections. The building was originally built to seat an audience of 10,000 and was commissioned by then First Lady Imelda Marcos in 1974 for the Miss Universe Pageant, which was to be held in Manila. The theater was built in record time of seventy-seven days in time for the pageant and was designed by Leandro V. Locsin.

It was host to many popular musical acts of the 1980s onwards, including Puerto Rican group Menudo, British pop group 5ive, Janet Jackson, Gary Valenciano and Jay R. The Folk Arts Theater is also used as a site by different religious groups. Day by Day Christian Ministries, a large international religious organization, has leased the area since 2005. They have dedicated the Theatre as Bulwagan ng Panginoón (English: Hall of the Lord). The building is expected to be torn down in the future, subject to the development of the Complex.

National Arts Center

The Cultural Center of the Philippines administers the National Arts Center, a 13.5 hectare complex at the Makiling Forest Reservation in Los Baños, Laguna. The complex hosts the Philippine High School for the Arts. Its flagship venue is the Tanghalang Maria Makiling, an open-air auditorium that can seat up to 1,800 people. The theater, which was also designed by Leandro V. Locsin, sits on a square plan dominated by a soaring pyramidal roof clad in clay tiles, a more literal interpretation of indigenous Filipino architecture when compared to the architect's previous works for the CCP.

Expansion

A comprehensive master plan for development of the complex was unveiled in 2003. The plan would divide the CCP complex into six clusters, each of which will be anchored by a major building. First, the Promenade, which will tentatively be named after Lucresia Reyes-Urtula, will include retail and other mixed-use facilities, as well as dock facilities. The second cluster will be the Arts Sanctuary, which will serve as the complex's cultural core. To be anchored by the Tanghalang Pambansa, it will contain a new performing arts theater, the artists' center, a bandstand, the Center's Production Design Center, as well as other open areas.

The third cluster, the Green Zone will contain a mix of museums, parks with commercial and office spaces. Fourth, the Creative Hub cluster, containing spaces for creative industries. Fifth, The Arts Living Room, envisioned to be a high-density, high-rise area that will house condominiums and similar residential projects. The final cluster, the Breezeway, will be located by low-rise, low-density commercial structures with seafront entertainment facilities. Covered walkways, plazas and bicycle lanes are planned to connect the various buildings and clusters to ensure a pedestrian-centered design. The master plan is envisioned to be completed in four phases, from 2004 to 2014; ₱5 billion will be needed for the plan's first five years, and another ₱8 billion for the plan's latter half.[31] A design contest was held in 2005 to design the first two clusters. Three firms won for their concepts; Syndicated Architects, Manalang-Tayag-Ilano Architects, and JPA Buensalido Design. The concepts of each winner will then be presented to prospective investors and stakeholders for approval.[32]

Syndicated Architects

Syndicated Architects JP Buensalido Designs

JP Buensalido Designs Manalang-Tayag-Ilano Architects

Manalang-Tayag-Ilano Architects

In 2011, Leandro V. Locsin Partners, Architects won the design contest for the Artists' Center and Performing Arts Theater, the two buildings that will anchor the Promenade and Arts Sanctuary Clusters respectively.[33] The proposed Artists' Center will house offices and rehearsal spaces for the CCP's resident companies, a black box theater and rooms for educational programs.[1] The winning design is akin to a traditional Badjao village or a mangrove forest, with rooms and pavilions supported by slim pilotis. The proposed Performing Arts Theater will contain a 1,000 seat conventional proscenium theater and a black box that will seat 300-500 people.[1] In contrast with the Tanghalang Pambansa's massive travertine block, the façade of the new theater will be dominated by its main seating bowl clad in reflective material, evoking a wave rising out of the sea.

The new expansion, CCP Black Box Theater, broke ground on January 19, 2016. It is estimated to cost PHP50 million and it will open after 8–12 months of construction. It will be three to four times bigger than Tanghalang Huseng Batute, the current black box theater in the complex.[34]

Satellite venues

In response to the need to widen its audience for the arts and to bring its programs closer to the people, the CCP has established a programmatic partnership with the Assumption Antipolo and De La Salle Santiago-Zobel School (DLSZ) in Alabang, Muntinlupa. As CCP's Satellite Venues in the East and in the South, these institutions commit to benefit from the exchange of goodwill and assistance through move-over productions, performances and artistic training workshops. Eventually, the center hopes to establish another satellite venue in the Northern part of Metro Manila.

The Angelo King Center for the Performing Arts

De La Salle-Santiago Zobel School established the Angelo King Center for the Performing Arts in 2000 with the aim of supporting the holistic development of its students. The Center pushed the development of theatrical and musical talents on campus. Activities, which have been organized at the Center, have been facilitated by highly acclaimed one located in this part of Metro Manila.

The Assumpta Theater, Assumption Antipolo

The Assumpta Theater was constructed in 1999 and inaugurated in 2001 and is located on the campus of Assumption Antipolo. It was envisioned to be a major cultural seat in eastern Metro Manila and to serve as a venue for cultural education and development not only of its students, faculty and parents but also for members of outside communities and schools neighboring municipalities of the Rizal Province.

The Assumpta Theater is home to modern light and sound equipment, 17 manual fly battens, a manual curtain system, a spacious stage area, an orchestra pit, fully air-conditioned dressing rooms, a docking area, stage wings, three-level seating arrangements, a lobby, and comfort rooms. The house area can accommodate 2,001 guests.

See also

- Arts of the Philippines

- Culture of the Philippines

- National Commission for Culture and the Arts

- National Arts Center

Notes

- ↑ The Cultural Center of the Philippines Complex lies between Pasay and the City of Manila. The boundary between the cities is Vicente Sotto Street. Landmarks in CCP Complex that lies within the City of Manila include the Tanghalang Pambansa (National Theater), the Tanghalang Francisco Balagtas (Folks Art Theater), and the Coconut Palace which is owned by the Government Service Insurance System.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 CCP Architectural Design Competition Background Information. Cultural Center of the Philippines. Retrieved 9 October 2011 Full Text available here.

- 1 2 Presidential Decree No. 15 s. 1972 "Creating the Cultural Center of the Philippines, defining its objectives, powers and functions and for other purposes". Full Text available here

- ↑ Executive No. 80 s. 1999 "Transferring the Cultural Center of the Philippines, Commission on Filipino Language, National Museum, National Historical Institute, National Library, and Records Management and Archives Office to the National Commission for Culture and the Arts for Policy Coordination to the National Commission for Culture and the Arts for Policy Coordination". Full Text available here.

- ↑ "The National Artists of the Philippines - Leandro V. Locsin". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Timeline". Genesis. Cultural Center of the Philippines. 1 (1). December 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Lico, Gerald (2003). Edifice Complex: Power, Myth and Marcos State Architecture. Quezon City, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press. pp. 178 p. ISBN 971-550-435-3.

- ↑ Santos, Tina (9 August 2008). "Hint of nostalgia on site of Manila Grand Opera House". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- 1 2 Ocampo, Ambeth (25 August 2011). "Sanctuary for the Filipino Soul". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ↑ Cannon, Lou (2000). President Reagan: the role of a lifetime. PublicAffairs. p. 920. ISBN 978-1-891620-91-1.

- ↑ "Folk Arts Theater". DM Consuji, Inc. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ↑ Martinez-Manaquil, Millet (December 2009). "Imelda Marcos: Where is the spirit? Where is the soul?". Genesis. Cultural Center of the Philippines. 1 (1).

- 1 2 3 Tiongson, Nicanor (December 2009). "The Winds of Change: 1986-1994". Genesis. Cultural Center of the Philippines. 1 (1).

- ↑ "CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art". Open Library. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ↑ Aning, Jerome (November 22, 2005). "Grand Dame ready for another facelift". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

- ↑ "Proclamation No.1001". The Official Gazette. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ↑ "Proclamation No.1144". The Official Gazette. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ↑ "CCP spearheads Sopas, Sining at Sorbetes outreach program for children". Philippine Entertainment Portal. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ↑ "A feast for the senses, food for the soul; Pasinaya Festival opens National Arts Month at CCP". Manila Bulletin. January 30, 2008. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ↑ Playwright named CCP artistic director. ABS-CBN News Online. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ The CCP Board of Trustees. Cultural Center of the Philippines. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ http://culturalcenter.gov.ph/about-the-ccp/ccp-officials/

- ↑ "Reclamation". Philippine Reclamation Authority. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ Republic Act No. 10066 "Providing for the protection and conservation of the national cultural heritage, strengthening the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) and its affiliated cultural agencies, and for other purposes". Full Text available here

- ↑ Vanzi, Sol Jose. "Cultural Center of the Philippines Get Facelift for IPU Meet". Philippine Headline News Online. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ↑ Klassen, Winard (1986). Architecture in the Philippines: Filipino building in a cross-cultural context. Cebu City: University of San Carlos Press.

- ↑ Bautista, BNN (2000). Philippine architecture 1948-1978. Reyes Publishing.

- ↑ Tanghalang Nicanor Abelardo: Technical Rider. Cultural Center of the Philippines. Retrieved 28 October 2011 Full Text available here.

- ↑ "CCP Acoustics: The Music of Sound". Cultural Center of the Philippines. Archived from the original on April 5, 2004. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ Taubman, Howard (10 September 1969). "A Gala premiere opens Manila's cultural center". New York Times.

- ↑ Tanghalang Aurelio Tolentino: Technical Rider. Cultural Center of the Philippines. Retrieved 28 October 2011 Full Text available here.

- ↑ ‘Commercialized’ CCP embraces the poor. ABS-CBN News Online. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ 3 architect groups win CCP design contest. ABS-CBN News Online. Retrieved 3 March 2012 Archived here.

- ↑ "Architectural Design Competition Exhibit Opens at CCP". GMA News Online. 5 September 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ http://lifestyle.inquirer.net/221508/after-3-decades-and-against-all-odds-ccp-breaks-ground-on-a-new-theater#ixzz3zUSyMLRL

Literature

- Lenzi, Iola (2004). Museums of Southeast Asia. Singapore: Archipelago Press. p. 200 pages. ISBN 981-4068-96-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cultural Center of the Philippines. |

- Cultural Center of the Philippines official website

- Cultural Center of the Philippines | An Introduction

- David Dubal interview with Raul Sunico, WNCN-FM, 4-Jun-1982