Firehose instability

The firehose instability (or hose-pipe instability) is a dynamical instability of thin or elongated galaxies. The instability causes the galaxy to buckle or bend in a direction perpendicular to its long axis. After the instability has run its course, the galaxy is less elongated (i.e. rounder) than before. Any sufficiently thin stellar system, in which some component of the internal velocity is in the form of random or counter-streaming motions (as opposed to rotation), is subject to the instability.

The firehose instability is probably responsible for the fact that elliptical galaxies and dark matter haloes never have axis ratios more extreme than about 3:1, since this is roughly the axis ratio at which the instability sets in.[1] It may also play a role in the formation of barred spiral galaxies, by causing the bar to thicken in the direction perpendicular to the galaxy disk.[2]

The firehose instability derives its name from a similar instability in magnetized plasmas.[3] However, from a dynamical point of view, a better analogy is with the Kelvin–Helmholtz instability,[4] or with beads sliding along an oscillating string.[5]

Stability analysis: sheets and wires

The firehose instability can be analyzed exactly in the case of an infinitely thin, self-gravitating sheet of stars.[4] If the sheet experiences a small displacement in the direction, the vertical acceleration for stars of velocity as they move around the bend is

provided the bend is small enough that the horizontal velocity is unaffected. Averaged over all stars at , this acceleration must equal the gravitational restoring force per unit mass . In a frame chosen such that the mean streaming motions are zero, this relation becomes

where is the horizontal velocity dispersion in that frame.

For a perturbation of the form

the gravitational restoring force is

where is the surface mass density. The dispersion relation for a thin self-gravitating sheet is then[4]

The first term, which arises from the perturbed gravity, is stabilizing, while the second term, due to the centrifugal force that the stars exert on the sheet, is destabilizing.

For sufficiently long wavelengths:

the gravitational restoring force dominates, and the sheet is stable; while at short wavelengths the sheet is unstable. The firehose instability is precisely complementary, in this sense, to the Jeans instability in the plane, which is stabilized at short wavelengths, .[6]

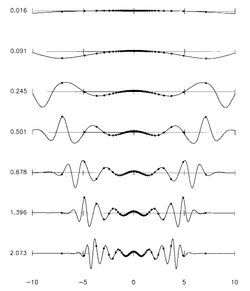

A similar analysis can be carried out for a galaxy that is idealized as a one-dimensional wire, with density that varies along the axis.[7] This is a simple model of a (prolate) elliptical galaxy. Some unstable eigenmodes are shown in Figure 2 at left.

Stability analysis: finite-thickness galaxies

At wavelengths shorter than the actual vertical thickness of a galaxy, the bending is stabilized. The reason is that stars in a finite-thickness galaxy oscillate vertically with an unperturbed frequency ; like any oscillator, the phase of the star's response to the imposed bending depends entirely on whether the forcing frequency is greater than or less than its natural frequency. If for most stars, the overall density response to the perturbation will produce a gravitational potential opposite to that imposed by the bend and the disturbance will be damped.[8] These arguments imply that a sufficiently thick galaxy (with low ) will be stable to bending at all wavelengths, both short and long.

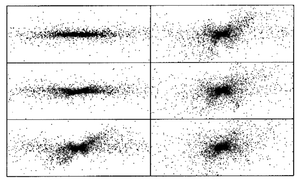

Analysis of the linear normal modes of a finite-thickness slab shows that bending is indeed stabilized when the ratio of vertical to horizontal velocity dispersions exceeds about 0.3.[4][9] Since the elongation of a stellar system with this anisotropy is approximately 15:1 — much more extreme than observed in real galaxies — bending instabilities were believed for many years to be of little importance. However, Fridman & Polyachenko showed [1] that the critical axis ratio for stability of homogeneous (constant-density) oblate and prolate spheroids was roughly 3:1, not 15:1 as implied by the infinite slab, and Merritt & Hernquist[7] found a similar result in an N-body study of inhomogeneous prolate spheroids (Fig. 1).

The discrepancy was resolved in 1994.[8] The gravitational restoring force from a bend is substantially weaker in finite or inhomogeneous galaxies than in infinite sheets and slabs, since there is less matter at large distances to contribute to the restoring force. As a result, the long-wavelength modes are not stabilized by gravity, as implied by the dispersion relation derived above. In these more realistic models, a typical star feels a vertical forcing frequency from a long-wavelength bend that is roughly twice the frequency of its unperturbed orbital motion along the long axis. Stability to global bending modes then requires that this forcing frequency be greater than , the frequency of orbital motion parallel to the short axis. The resulting (approximate) condition

predicts stability for homogeneous prolate spheroids rounder than 2.94:1, in excellent agreement with the normal-mode calculations of Fridman & Polyachenko[1] and with N-body simulations of homogeneous oblate[10] and inhomogeneous prolate [7] galaxies.

The situation for disk galaxies is more complicated, since the shapes of the dominant modes depend on whether the internal velocities are azimuthally or radially biased. In oblate galaxies with radially-elongated velocity ellipsoids, arguments similar to those given above suggest that an axis ratio of roughly 3:1 is again close to critical, in agreement with N-body simulations for thickened disks.[11] If the stellar velocities are azimuthally biased, the orbits are approximately circular and so the dominant modes are angular (corrugation) modes, . The approximate condition for stability becomes

with the circular orbital frequency.

Importance

The firehose instability is believed to play an important role in determining the structure of both spiral and elliptical galaxies and of dark matter haloes.

- As noted by Edwin Hubble and others, elliptical galaxies are rarely if ever observed to be more elongated than E6 or E7, corresponding to a maximum axis ratio of about 3:1. The firehose instability is probably responsible for this fact, since an elliptical galaxy that formed with an initially more elongated shape would be unstable to bending modes, causing it to become rounder.

- Simulated dark matter haloes, like elliptical galaxies, never have elongations greater than about 3:1. This is probably also a consequence of the firehose instability.[12]

- N-body simulations reveal that the bars of barred spiral galaxies often "puff up" spontaneously, converting the initially thin bar into a bulge or thick disk subsystem.[13] The bending instability is sometimes violent enough to weaken the bar.[2] Bulges formed in this way are very "boxy" in appearance, similar to what is often observed.[13]

- The firehose instability may play a role in the formation of galactic warps.[14]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Fridman, A. M.; Polyachenko, V. L. (1984), Physics of Gravitating Systems. II — Nonlinear collective processes: Nonlinear waves, solitons, collisionless shocks, turbulence. Astrophysical applications, Berlin: Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-13103-0

- 1 2 Raha, N.; Sellwood, J. A.; James, R. A.; Kahn, F. A. (1991), "A dynamical instability of bars in disk galaxies", Nature, 352 (6334): 411–412, Bibcode:1991Natur.352..411R, doi:10.1038/352411a0

- ↑ Parker, E. N. (1958), "Dynamical Instability in an Anisotropic Ionized Gas of Low Density", Physical Review, 109: 1874–1876, Bibcode:1958PhRv..109.1874P, doi:10.1103/PhysRev.109.1874

- 1 2 3 4 Toomre, A. (1966), "A Kelvin–Helmholtz Instability", Notes from the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Summer Study Program, Woods Hole Oceanographic Inst.: 111–114

- ↑ In spite of its name, the firehose instability is not related dynamically to the oscillatory motion of a hose spewing water from its nozzle.

- ↑ Kulsrud, R. M.; Mark, J. W. K.; Caruso, A. (1971), "The Hose-Pipe Instability in Stellar Systems", Astrophysics and Space Science, 14: 52–55, Bibcode:1971Ap&SS..14...52K, doi:10.1007/BF00649194.

- 1 2 3 Merritt, D.; Hernquist, L. (1991), "Stability of Nonrotating Stellar Systems", The Astrophysical Journal, 376: 439–457, Bibcode:1991ApJ...376..439M, doi:10.1086/170293.

- 1 2 Merritt, D.; Sellwood, J. (1994), "Bending Instabilities of Stellar Systems", The Astrophysical Journal, 425: 551–567, Bibcode:1994ApJ...425..551M, doi:10.1086/174005

- ↑ Araki, S. (1985). "A Theoretical Study of the Stability of Disk Galaxies and Planetary Rings. PhD Thesis, MIT". OCLC 13915550.

- ↑ Jessop, C. M.; Duncan, M. J.; Levison, H. F. (1997), "Bending Instabilities in Homogenous Oblate Spheroidal Galaxy Models", The Astrophysical Journal, 489: 49–62, Bibcode:1997ApJ...489...49J, doi:10.1086/304751

- ↑ Sellwood, J.; Merritt, D. (1994), "Instabilities of counterrotating stellar disks", The Astrophysical Journal, 425: 530–550, Bibcode:1994ApJ...425..530S, doi:10.1086/174004

- ↑ Bett, P.; et al. (2007), "The spin and shape of dark matter haloes in the Millennium simulation of a Λ cold dark matter universe", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 376: 215–232, arXiv:astro-ph/0608607

, Bibcode:2007MNRAS.376..215B, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.11432.x

, Bibcode:2007MNRAS.376..215B, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.11432.x - 1 2 Combes, F.; et al. (1990), "Box and peanut shapes generated by stellar bars", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 233: 82–95, Bibcode:1990A&A...233...82C

- ↑ Revaz, Y.; Pfenniger, D. (2004), "Bending instabilities at the origin of persistent warps: A new constraint on dark matter halos", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 425: 67–76, arXiv:astro-ph/0406339

, Bibcode:2004A&A...425...67R, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20041386

, Bibcode:2004A&A...425...67R, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20041386