Excalibur (film)

| Excalibur | |

|---|---|

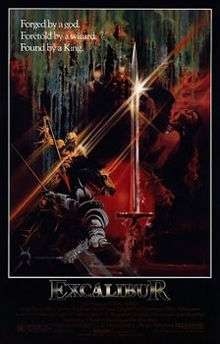

Theatrical release poster by Bob Peak | |

| Directed by | John Boorman |

| Produced by | John Boorman |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on |

Le Morte d'Arthur by Thomas Malory |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Trevor Jones |

| Cinematography | Alex Thomson |

| Edited by | John Merritt |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 140 minutes[1] |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $11 million[2] |

| Box office | $35 million[3] |

Excalibur is a 1981 British dramatic fantasy film directed, produced, and co-written by John Boorman that retells the legend of King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table. Based solely on the 15th century Arthurian romance, Le Morte d'Arthur by Thomas Malory, Excalibur stars Nigel Terry as Arthur, Nicol Williamson as Merlin, Nicholas Clay as Lancelot, Cherie Lunghi as Guenevere, Helen Mirren as Morgana, Liam Neeson as Gawain, Corin Redgrave as Cornwall, and Patrick Stewart as Leodegrance. The film is named after the legendary sword of King Arthur that features prominently in Arthurian literature. The film's soundtrack features the music of Richard Wagner and Carl Orff, along with an original score by Trevor Jones.

Shot entirely on location in Ireland and employing Irish actors and crew, the film has been acknowledged for its importance to the Irish filmmaking industry and for helping launch the film and acting careers of a number of Irish and English actors, including Mirren, Neeson, Stewart, Gabriel Byrne, Neil Jordan and Ciarán Hinds.[2]

Excalibur achieved moderate box office success while receiving mixed reviews. Although film critics Roger Ebert and Vincent Canby criticised the film's plot and characters,[4][5] they, along with other reviewers,[6] praised its visual style. Excalibur opened at number one in the United States, eventually grossing $34,967,437 on a budget of around US$11 million, to rank 18th in that year's receipts.[3]

Plot

The sorcerer Merlin retrieves Excalibur from the Lady of the Lake for Uther Pendragon, who secures a brief alliance with Gorlois, the Duke of Cornwall. Uther's lust for Cornwall's wife Igrayne soon ruins the truce, and Merlin agrees to help Uther to seduce Igrayne on the condition that he gives Merlin whatever results from his lust. Merlin transforms Uther into Cornwall's likeness with the Charm of Making. Cornwall's daughter Morgana senses her father's mortal injury during his assault on Uther's camp; and, while Igrayne is fooled by the disguise and Uther impregnates her, Morgana sees through it, watching Uther as Cornwall dies in battle. Nine months later, Merlin takes Uther's son Arthur. Uther pursues but is mortally wounded by Gorlois' knights. Uther thrusts Excalibur into a stone, crying that "None shall wield Excalibur, but me!", and Merlin proclaims, "He who draws the sword from the stone, he shall be king."

Years later Sir Ector and his sons, Kay and Arthur (Nigel Terry) attend a jousting tournament. Sir Leondegrance wins the chance to try pulling Excalibur from the stone, but he fails. Kay's sword is later stolen, and Arthur pulls Excalibur from the stone while trying to replace the stolen sword. Word spreads, and Merlin announces to the crowd that Arthur is Uther's son and, hence, the rightful ruler. Leondegrance immediately proclaims his support for the new king, but not all are willing to accept. While the others argue, Merlin and Arthur enter the forest, where Merlin tells Arthur that he is the rightful king and that the king and the land are one. Overwhelmed, Arthur falls into a long sleep. When he wakes, Arthur goes to aid Leondegrance, whose castle is under siege by Arthur's enemies, led by Sir Uryens. During the battle, Arthur defeats Uryens and then demands Uryens knight him, handing him Excalibur to do so. Uryens is tempted to kill him but is deeply moved by Arthur's display of faith and decides to knight him (Merlin is stunned by something he did not foresee). Uryens falls to his knees to declare his loyalty, which leads the others to follow suit. Arthur meets Leondegrance's daughter Guinevere soon afterwards and is smitten but Merlin foresees trouble.

Years later, the undefeated knight Lancelot blocks a bridge and will not move until he is defeated in single combat, seeking a king worthy of his sword. Lancelot defeats Arthur and his knights, so Arthur summons Excalibur's magic and defeats Lancelot but breaks Excalibur. Arthur is ashamed of abusing the sword's power to serve his own vanity and throws the sword's remains into the lake, while admitting his mistake. The Lady of the Lake offers a restored Excalibur to the king, Lancelot is revived and Arthur and his knights unify the land. Arthur creates the Round Table, builds Camelot and marries Guinevere; Lancelot confesses that he has fallen in love with her too. Arthur's half-sister Morgana, a budding sorceress and still bitter towards Arthur, becomes apprenticed to Merlin in hopes of learning the Charm of Making from him.

Lancelot stays away from the Round Table to avoid Guenevere. He meets Perceval, a peasant boy and takes him to Camelot to become a squire. Sir Gawain, under Morgana's influence, accuses Guinevere of driving Lancelot away, "driven from us by a woman's desire", forcing Lancelot to duel with Gawain to defend his and Guinevere's honour. The preceding night, Lancelot is attacked by himself in a nightmare and awakens to find himself wounded by his own sword. Arthur hastily knights Perceval when Lancelot is late to the duel but Lancelot appears just in time and defeats Gawain, while nearly dying from his wounds. Merlin heals him and he rides out to the forest to rest. Guenevere realises her feelings for Lancelot and they consummate their love in the forest; meanwhile, Merlin lures Morgana to his lair to trap her, suspecting that she is plotting against Arthur.

Arthur finds Guenevere and Lancelot asleep together. Heartbroken at their betrayal, he thrusts Excalibur into the ground between the sleeping couple. Merlin's magical link to the land impales him on the sword and Morgana seizes the opportunity to trap him in a crystal, with the Charm of Making. Morgana takes the form of Guinevere and seduces Arthur. On awakening to the sight of Excalibur, Lancelot flees in shame and Guinevere lies weeping.

Morgana bears a son, Mordred and a curse caused by Mordred's unnatural, incestuous origin, strikes the land with famine and sickness. A broken Arthur sends his knights on a quest for the Holy Grail, in hopes of restoring the land. Many of his knights die or are bewitched by Morgana. Morgana captures Perceval, who narrowly escapes. Perceval encounters an ugly bearded old man with armour under his tattered robes, who preaches to followers that the kingdom has fallen because of "the sin of Pride". A shocked Perceval recognises the man as Lancelot. After Perceval fails to convince Lancelot to come to Arthur's aid, Lancelot and his followers throw Perceval into a river. Perceval has a vision of the Grail, during which he realises that Arthur and the land are one. Upon answering the riddle he gains the Grail and takes it to Arthur, who drinks from it and is revitalised, as is the land, which springs into blossom.

Arthur finds Guinevere at a convent and they reconcile. She gives him Excalibur, which she has kept safe since the day she fled. Frustrated in preparation for battle against Morgana's allies, Arthur calls to Merlin, unknowingly awakening the wizard from his enchanted slumber. Merlin and Arthur have a last conversation before Merlin vanishes. The wizard then appears to Morgana as a shadow and tricks her into uttering the Charm of Making, producing a fog from the breath of the Dragon, and exhausting her own magical powers which had kept her young. She rapidly ages and her own son kills her, repulsed by the sight of his once beautiful mother now reduced to a decrepit old crone.

Arthur and Mordred's forces meet in battle, with Arthur's army benefiting from the fog that conceals their small size. Lancelot arrives unexpectedly and turns the tide of battle, later collapsing from his old, self-inflicted wound which had never healed. Arthur and Lancelot reconcile and Lancelot dies with honour. Mordred stabs Arthur with a spear but Arthur further impales himself to get closer and kills Mordred with Excalibur. Perceval refuses to carry out Arthur's dying wish, that he throw Excalibur into a pool of calm water, reasoning that the sword is too valuable to be lost. Arthur tells him to do as he commands and reassures him that one day a new king will come and the sword will return again. Perceval throws Excalibur into the pool, where the Lady of the Lake catches it. Perceval returns to see Arthur lying on a ship, attended by three ladies clad in white, sailing into the sun toward the Isle of Avalon.

Cast

- Nigel Terry as King Arthur

- Helen Mirren as Morgana Le Fay

- Kay McLaren as the aged Morgana

- Barbara Byrne as the young Morgana

- Nicholas Clay as Sir Lancelot

- Cherie Lunghi as Queen Guenevere

- Paul Geoffrey as Sir Perceval

- Nicol Williamson as Merlin[5]

- Corin Redgrave as Duke of Cornwall

- Patrick Stewart as King Leondegrance

- Keith Buckley as Sir Uryens

- Clive Swift as Sir Ector

- Liam Neeson as Sir Gawain

- Gabriel Byrne as Uther Pendragon

- Robert Addie as Prince Mordred (as an adult)

- Charley Boorman as young Mordred

- Katrine Boorman as Igrayne, Duchess of Cornwall

- Ciarán Hinds as King Lot

- Niall O'Brien as Sir Kay

Even though he was 35 years old, Nigel Terry plays King Arthur from his teenage years to his ending as an aged monarch.

Several members of the Boorman family also appear: his daughter Katrine played Igrayne, Arthur's mother, and his son Charley portrayed Mordred as a boy. Because of the number of Boormans involved with the film, it is sometimes called "The Boorman Family Project".[7]

Production

Origin

Boorman had planned a film adaptation of the Merlin legend as early as 1969, but the studio he offered it to (United Artists) rejected his concept, offering him J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings instead. When Boorman, having written a three-hour-one-film-script with Rospo Pallenberg, submitted the film script to United Artists, they rejected it, deeming it too costly. Boorman was allowed to shop the script elsewhere, but no studio would commit to it. Returning to the original idea of the Merlin legend, Boorman was eventually able to secure deals that would help him do Excalibur instead. Much of the imagery and set designs seen in the film were originally created with The Lord of the Rings in mind.[8]

According to Boorman, the film was originally three hours long; among scenes that were deleted from the finished film but featured in one of the promotional trailers was a sequence where Lancelot rescued Guenevere from a forest bandit.

Casting

Boorman cast Nicol Williamson and Helen Mirren opposite each other as Merlin and Morgana, knowing that the two were on less than friendly terms due to personal issues that arose during a production of Macbeth seven years earlier. Boorman felt that the tension on set would come through in the actors' performances. This is stated by Boorman himself in the audio commentary track of the Excalibur DVD.

Filming

Excalibur was filmed in Irish locations in County Wicklow, County Tipperary, and County Kerry. The early critical battle scene around a castle, in which Arthur is made a knight by Uryens, while kneeling in a moat, was filmed in Cahir Castle, in Cahir County Tipperary, Republic of Ireland, a well-preserved Norman castle. The castle's moat is the River Suir which flows around it. The fight with Lancelot was filmed at Powerscourt Estate's waterfall. Other locations included Wicklow Head as the backdrop to the battle over Tintagel, the Kerry coast as the place from which Arthur sails to Avalon and a place called Childers Wood near Roundwood, County Wicklow, where Arthur comes on Excalibur in the stone. At the time, John Boorman was living just a few miles down the road, at Annamoe.[9]

According to Boorman, the love scene between Lancelot and Guenevere in the forest was filmed on a very cold night, but Nicholas Clay and Cherie Lunghi performed the scene nude anyway.

Costumes

Bob Ringwood designed the costumes and received a BAFTA nomination for his work. Terry English designed the armour and went on to craft the armour for the film Aliens.

Adaptation

Rospo Pallenberg and John Boorman wrote the screenplay which is primarily an adaptation of Malory's Morte d'Arthur (1469–70) recasting the Arthurian legends as an allegory of the cycle of birth, life, decay, and restoration, by stripping the text of decorative or insignificant details. The resulting film is reminiscent of mythographic works such as Sir James Frazer's The Golden Bough and Jessie Weston's From Ritual to Romance; Arthur is presented as the "Wounded King" whose realm becomes a wasteland to be reborn thanks to the Grail, and may be compared to the Fisher (or Sinner) King, whose land also became a wasteland, and was also healed by Perceval. "The film has to do with mythical truth, not historical truth," Boorman remarked to a journalist during filming. The Christian symbolism revolves around the Grail, perhaps most strongly in the baptismal imagery of Perceval finally achieving the Grail quest. "That's what my story is about: the coming of Christian man and the disappearance of the old religions which are represented by Merlin. The forces of superstition and magic are swallowed up into the unconscious."[10][11]

In keeping with this approach, the film is intentionally anachronistic.[10] For example, the opening titles state the setting to be the Dark Ages, even though the knights wear full plate armour, a technology of the 15th century. Knights, knighthood and the code of chivalry also did not exist during the period. Furthermore, Britain is never mentioned by name, only as "the land".

.jpg)

In addition to Malory, the writers incorporated elements from other Arthurian stories, sometimes altering them. For example, the sword between the sleeping lovers' bodies comes from the tales of Tristan and Iseult; the knight who returns Excalibur to the water is changed from Bedivere to Perceval; and Morgause and Morgan Le Fay are merged into one character.

The sword Excalibur and the Sword in the Stone are presented as the same thing; in some versions of the legends they are separate. In Le Morte d'Arthur, Sir Galahad, the illegitimate son of Lancelot and Elaine of Carbonek, is actually the Knight who is worthy of the Holy Grail. Boorman follows the earlier version of the tale as told by Chrétien de Troyes, making Perceval the grail winner.

Some new elements were added, such as Uther wielding Excalibur before Arthur (repeated in Merlin), Merlin's 'Charm of Making' (written in Old Irish), and the concept of the world as "the dragon" (probably inspired by the dragon omen seen in Geoffrey of Monmouth's account of Merlin's life).

The Charm of Making

According to linguist Michael Everson, the "Charm of Making" that Merlin speaks to invoke the dragon is an invention, there being no attested source for the charm. Everson reconstructs the text as Old Irish.[12][13][14] The phonetic transcription of the charm as spoken in the film is [aˈnaːl naθˈrax, uːrθ vaːs beˈθʌd, doxˈjeːl ˈdjenveː]. Although the pronunciation in the film has little relation to how the text would actually be pronounced in Irish, the most likely interpretation of the spoken words, as Old Irish text is:[15]

- Anál nathrach,

- orth’ bháis’s bethad,

- do chél dénmha

In modern English, this can be translated as:

- Serpent's breath,

- charm of death and life,

- thy omen of making.

Soundtrack

The soundtrack consists of original music composed by Trevor Jones, with the inclusion of classical pieces from Orff's Carmina Burana, as well as from Wagner's Ring and Tristan und Isolde operas.[16]

- Part of Siegfried's Funeral March from Götterdämmerung was used as the main theme.

- Orff's "O Fortuna" is heard during two scenes when Arthur and his knights ride out to do battle.

- The theme between Lancelot and Guenevere is the prelude to Wagner's "Tristan und Isolde", a piece about the romance of Sir Tristram and Iseult, another pair of lovers from the Arthurian tales.

- The theme of Perceval and the Grail is the prelude to Wagner's "Parsifal".

Reception

Excalibur was the number one film during its opening weekend of 10–12 April 1981, eventually earning $34,967,437 in the United States.[3]

Reviews were mixed. Widely hailed for its visuals, setting and overall design, other elements such as the story and performances some critics found wanting. Roger Ebert, for instance, called it both a "wondrous vision" and "a mess."[4] Elaborating further, Ebert said the film was "a record of the comings and goings of arbitrary, inconsistent, shadowy figures who are not heroes but simply giants run amok. Still, it's wonderful to look at." Vincent Canby was more critical, saying that while Boorman took Arthurian myths seriously, "he has used them with a pretentiousness that obscures his vision."[17] In her review in The New Yorker, Pauline Kael said the film had its own "crazy integrity", adding that the imagery was "impassioned" with a "hypnotic quality". According to her, the dialogue, however, was "near-atrocious". She concluded by saying that "Excalibur is all images flashing by... We miss the dramatic intensity that we expect the stories to have, but there's always something to look at."[18]

Others have praised the entire film, with Variety calling it "a near-perfect blend of action, romance, fantasy and philosophy".[6] Sean Axmaker of Parallax View said, "John Boorman's magnificent and magical Excalibur is, to my mind, the greatest and the richest of screen incarnation of the oft-told tale."[19] In a later review upon the film's DVD release, Salon's David Lazarus noted the film's contribution to the fantasy genre, stating that it was "a lush retelling of the King Arthur legend that sets a high-water mark among sword-and-sorcery movies."[20] A recent study by Jean-Marc Elsholz demonstrates how closely the film Excalibur was inspired by the Arthurian romance tradition and its intersections with medieval theories of light, most particularly in the aesthetic/visual narrative of Boorman's film rather than in its plot alone.[21]

Excalibur currently has an 82% "fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes.[22]

The film featured many actors early in their careers who later became very well-known, including Helen Mirren, Patrick Stewart, Liam Neeson, Gabriel Byrne, and Ciarán Hinds playing Morgana, Leondegrance, Gawain, Uther Pendragon, and King Lot respectively. For his performance as Merlin, Nicol Williamson received widespread acclaim. The Times in 1981 wrote: "The actors are led by Williamson's witty and perceptive Merlin, missed every time he's offscreen".

Accolades

Alex Thomson, the film's cinematographer, was nominated for Best Cinematography at the 1982 Academy Awards, but lost to Vittorio Storaro for Reds.

Boorman won the prize for Best Artistic Contribution, and was nominated for a Palme d'Or, at the 1981 Cannes Film Festival.[23]

Criticism

One critic, Felice Lifshitz, has noted her displeasure with the representation of women in this film. Morgana Le Fay is painted as a vengeful, emotionally driven witch, which is highlighted in the Mordred birth scene, which looks like a satanic rite.[24] Morgana is lying on an altar dressed in black and surrounded by faceless servants also dressed in black. Lightning flashes all around as Mordred is born, giving the illusion of satanic worship; it has been argued that this contradicts Malory’s representation of Morgana. In Malory, Morgana is a device used to test the abilities and make sure the Knights were worthy to sit at the Round Table; Morgana helps send Arthur to Avalon where she will be his protector and healer.[25] Other critics points out that Guinevere and the Lady of the Lake have lesser roles. Guinevere was originally the representation of a successful governing queen with the ability to balance her personal life and her royal duties.[26] Excalibur shows her as the downfall of Camelot, with little attention paid to her royal abilities. The Lady of the Lake is all but ignored in Excalibur, while in Malory’s tale she was essential to the plot, learning sorcery from Merlin and protecting Arthur.[27]

In defence of his work, Boorman has said that Excalibur is merely about myths and Jungian archetypes, built on the idea of humans moving past their primal ways and on to civilization. He did not set out to appropriate stereotypes, he wanted to tell a story about men saying, “My whole life I’ve been surrounded by women, and perhaps I try to escape from that in my films… So in this film I tried to explore the world of men.”[28]

Classifications and versions

When first released in the United Kingdom in 1981, the film ran to 140m 30s, and was classified as a "AA" by the BBFC, restricting it to those aged 14 and over.[1] In 1982, the BBFC replaced the "AA" certificate with the higher age-specific "15", which was also applied to Excalibur when released on home video.[29]

The 140-minute version was initially released in the United States with an R-rating. Distributors later announced a 119m PG-rated version, with less graphic sex and violence, but it was not widely released. Most home video releases are the R-rated version, but commercial TV channels may use the PG cut.

When Excalibur first premiered on HBO in 1982, the R-rated version was shown in the evening and the PG-rated version was shown during the daytime, following the then current rule of HBO only showing R-rated films during the evening hours.

2013 documentary

A documentary entitled Behind the Sword in the Stone is currently in production featuring interviews with director Boorman and many of the cast, such as Terry, Mirren, Stewart, Neeson, Byrne, Lunghi, and Charley Boorman.[30][31]

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Excalibur (film) |

- List of American films of 1981

- Excalibur, King Arthur's sword, the central symbol of kingship for Malory and the film

- List of films based on Arthurian legend

- List of sword and sorcery films

References

- 1 2 "Excalibur (AA)". British Board of Film Classification. 1 April 1981. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- 1 2 Doyle, Rónán (27 January 2011). "Boorman honoured as 'Excalibur' hits 30". Film Ireland. Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- 1 2 3 "Excalibur". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- 1 2 Ebert, Roger. "Excalibur". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

What a wondrous vision EXCALIBUR is! And what a mess.

- 1 2 Canby, Vincent (10 April 1981). "Boorman's 'Excalibur'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

Except for the performances of Nicol Williamson... and Helen Mirren... the movie seems to be a beautiful, uninhabited, primeval forest.

- 1 2 "Excalibur". Variety. 31 December 1980. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ↑ Manwaring, Kevan (5 October 2009). "Brilliant Failures: Excalibur (John Boorman, 1981)". The Big Picture. ISSN 1759-0922. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ↑ Boorman, John (1 November 2003). Adventures of a Suburban Boy. Faber Books. pp. 178ff. ISBN 978-0571216956. Retrieved 2014-07-17. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Manthey, Dirk, ed. (1981). Excalibur. Cinema Programme 27. pp. 15, 20.

- 1 2 Kennedy, Harlan (March 1981). "John Boorman in Interview". American Film. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ↑ "The Quest for the Hollywood Grail John Boorman's Excalibur, and the Mythic Development of the Arthurian Legend (sic)". Archived from the original on 25 June 2006. Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- ↑ Everson, Michael. "Merlin's Charm of Making". Evertype. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ↑ "Indo-European etymology: *ane-". Retrieved 22 March 2011.

Anál: to breathe, to blow *anǝtlo-: OIr anāl 'spiritus'; Cymr anadl 'Atem'; MBret alazn (Umstellung), Bret holan; *anǝtī-: MCymr eneit, Cymr eneid 'Seele'; *anamon-: OIr animm, gen. anman, Ir anam 'Seele'

- ↑ "Indo-European etymology: *nētr-". Retrieved 22 March 2011.

Nathrach: Celtic: *natrī > OIsl nathir, gen. nathrach 'natrix, serpens'; Corn nader `Schlange', OBret pl. natrol-ion 'Basilisken', MBret azr 'Schlange', NBret aer ds., Cymr neidr, pl. nadroedd 'ds.'

- ↑ Bourgne, Florence; Carruthers, Leo M.; Sancery, Arlette (2008). Un espace colonial et ses avatars: naissance d'identités nationales, Angleterre, France, Irlande, Ve-XVe siècles (in French). Volume 42 di Cultures et civilisations médiévales. Editor: Florence Bourgne. Presses Paris Sorbonne. p. 4. ISBN 9782840505594.

serpent's [dragon's] breath, charm of death and life, thy spell of making

- ↑ "Soundtracks for Excalibur". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ↑ Canby, Vincent (10 April 1981). "Boorman's 'Excalibur'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ↑ Kael, Pauline (20 April 1981). "Boorman's Plunge". The New Yorker: 146–151. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ↑ Axmaker, Sean. "Excalibur". Parallax View. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ↑ Lazarus, David (7 September 2000). "Excalibur". Salon. Salon.com. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ↑ Elsholz, Jean-Marc (3 March 2011). "Elucidations: Bringing to Light the Aesthetic Underwriting of the Matière de Bretagne in John Boorman's Excalibur". In Carruthers, Leo; Chai-Elsholz, Raeleen; Silec, Tatjana. Palimpsests and the Literary Imagination of Medieval England. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 205–26. ISBN 978-0230100268. Retrieved 2014-07-17. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Excalibur (1981)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: Excalibur". Festival de Cannes. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ↑ Lifshitz, Felice (2012). "Destructive Dominae: Woman and Vengeance in Medevalist Films". In Fugelso, Karl. Corporate Medievalism. Cambridge. pp. 174–175.

- ↑ Lifshitz, Felice (2012). "Destructive Dominae: Woman and Vengeance in Medevalist Films". In Fugelso, Karl. Corporate Medievalism. Cambridge. p. 173.

- ↑ Lifshitz, Felice (2012). "Destructive Dominae: Woman and Vengeance in Medevalist Films". In Fugelso, Karl. Corporate Medievalism. Cambridge. p. 178.

- ↑ Lifshitz, Felice (2012). "Destructive Dominae: Woman and Vengeance in Medevalist Films". In Fugelso, Karl. Corporate Medievalism. Cambridge. p. 174.

- ↑ Wakeman, Ray (1998). "Excalibur: Film Reception and Political Distance". In Bjorkmund, Beth; Cory, Mary E. Politics in German Literature. Columbia, SC. pp. 171–172.

- ↑ BBFC: Excalibur', video, 7 November 1986

- ↑ "Behind the Sword in the Stone". Indiegogo. 1 December 2012. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ↑ Hall, Eva (20 December 2012). "'Excalibur' Documentary Wraps Principal Photography In Ireland". Irish Film and Television Network. Retrieved 2014-07-17.