Equative

| Linguistics |

|---|

| Theoretical |

| Descriptive |

| Applied and experimental |

| Related articles |

| Linguistics portal |

The term equative is used in linguistics to refer to constructions where two entities are equated with each other. For example, the sentence Susan is our president, equates two entities "Susan" and "our president". In English, equatives are typically expressed using a copular verb such as "be", although this is not the only use of this verb. Equatives can be contrasted with predicative constructions where one entity is identified as a member of a set, such as Susan is a president.

Different world languages approach equatives in different ways. The major difference between languages is whether or not they use a copular verb or a non-verbal element (e.g. demonstrative pronoun) to equate the two expressions.

The term equative is also sometimes applied to comparative-like constructions in which the degrees compared are identical rather than distinct: e.g., John is as stupid as he is fat; some languages have a separate equative case.

Theories and debate

Debate on taxonomy

The taxonomy or classification of copular clauses proposed by Higgins is the starting point of much work on syntax and semantics of copular clauses. Higgins' taxonomy distinguishes between four types of copular clauses:

- Predicational

a. The hat is big. b. The hat/present/thing I bought for Harvey is big. c. What I bought for Harvey is big.

- Specificational

a. The director of Anatomy of Murder is Otto Preminger. b. The only director/person/one I met was Otto Preminger. c. Who I met was Otto Preminger.

- Identificational

a. That (woman) is Sylvia. b. That (stuff) is DDT.

- Equative

a. Sylvia Obernauer is HER. b. Cicero is Tully.

This taxonomy is based primarily on native speaker intuition, as well as on detailed observations of English copular sentences. The intuition about predicational clauses is that they predicate a property of the subject referent. The other three types of copular clauses do not involve predication. Equatives equate the referents of the two expressions on either side of the copular verb. Neither is a predicate of the other. Specificational clauses involve assigning a value to a variable: the subject expression sets up a variable and the post-copular expression provides the value for that variable. Identificational clauses typically involve a demonstrative subject and are used for teaching the names of people or of things. Many linguists are currently in disagreement regarding the taxonomy and status of equative clauses.

Reduction of taxonomy

Caroline Heycock [1] contributes to the discussion about whether specificational sentences are a special type of equatives or if they can be reduced to 'inverted predications': she argues that these sentences are a type of equative in which only one of the two noun phrases is a simple individual. Heycock claims that specificational sentences are an 'asymmetric' equation because the noun phrase that occurs in clause-initial position is interpreted as a more intentional subject than is the post-copular noun phrase.

Den Dikken [2] states that the category of specificational sentences is more real and that it includes both categories (specificational and equative clauses).

Mikkelsen, on the other hand, maintains the distinction between specificational and equative clauses, but suggests that the identificational class be eliminated.

Heller [3] goes further and gives a reduced taxonomy of two classes of clauses: predicational, which includes both identificational and predicational clauses, and equative, which involve equative and specificational clauses.

Debate on equatives

Linguists have also been arguing about the very existence of equative clauses as a separate class. There are languages that are claimed to lack equative constructions, e.g. Adger & Ramchand [4] analyze Scottish Gaelic as a language without equatives. Some languages use more elaborate locutions, e.g. be the same person as in English to express the meaning of the sentence like Cicero is Tully. Geist [5] claims that there are no monoclausal equatives in Russian. According to Geist, equation is mediated, syntactically and semantically, by a demonstrative pronoun. Mikkelsen argues that within English, outside special cases like Muhammad Ali is Cassius Clay, Mark Twain is Samuel CLemens, and Cicero is Tully, main clause equatives which involve two names are difficult to contextualize. However, equatives such as Sylvia Obernauer is HER, where one NP is a pronoun and the other is a name, are easier to contextualize: they are natural answers to Who is who? in a situation where individuals can be identified both by name or by sight, e.g. at the conference.

Halliday's semantic analysis of equatives

Halliday [6] divides clauses into two categories: 'intensive', where the process is ascription (the assigning of an attribute) and the equative, which is treated as a type of effective clause with the process being syntactically one of action rather than ascription. The intensive clause, like Mary is/seems happy, Mary was/became a teacher, is a non-reversible, one-participant type with the verb being of the copulative class ('class o': be, becomes, seem, look, sound, get, turn, etc.); the equative, like 'John is the leader', is a reversible, two-participant type with the verb being of the equative sub-class (of 'class 2': be, equal, resemble, realize, represent, etc.).

The equative relates an 'identifier' with a 'thing to be identified', as in ('who is John?') // John is the leader //. This relates to the underlying WH-question, and either the identified or the identifier may come first in sequence. The equative has two interpretations, as decoding or as encoding: // John is the leader // as a decoding equative has the interpretation 'John realizes, has the function of the leader', with John as the variable and the leader as a value, and as an encoding equative has the interpretation' John is realized by, has the form of the leader', with John as value and the leader as variable. According to Halliday, all equative clauses are therefore ambiguous, for example:

The noisiest ones are the freshmen. *Decoding: 'you notice those noisiest ones there? well they're freshmen' *Encoding: 'you want to know who makes the most noise? the freshmen do' What they're selling might be sports clothes. *Decoding: 'what are those things they're selling? they might be sports clothes' *Encoding: 'what do they sell? they might sell sports clothes'

Copular equative constructions

Chinese

Mandarin Chinese exhibits both DP-DP and DP-CP structures, and it is classified as having copular equative construction because there is overt copula. The copular verb 是 shì can be used in both of these structures.

DP = DP

There is only one copular verb in Chinese, 是 shì, which is used as an equative verb. This verb is necessary when the complement of the sentence is a noun phrase.

(1) 我是中国人。 wǒ shì Zhōnggúorén.

I-NOM COP Chinese (person).

'I am Chinese.'

In classical Chinese before the Han Dynasty, the verb 是 served as a demonstrative pronoun meaning "this".[7] In modern Chinese, the complementizer 的 de is needed at the end of a noun phrase that changes the category to an adjectival phrase. Consider the following two sentences:

(2) a. *我的靴子是红色。 wǒde xuēzi shì hóngsè.

I-POSS GEN COP red (color).

*'My boot(s) is(are) red.'

b. 我的靴子是红色的。 wǒde xuēzi shì hóngsè de.

I-POSS GEN COP red (color) COMPL.

'My boot(s) is(are) red.'

Whilst the two sentences aim to express the same meaning, only the second one is grammatical. The first cannot equate ’red' and 'boot(s)' without using the modifier 的 de.

DP = CP

The example below illustrates how a DP can be equated with a CP clause by employing the copular verb 是 shì.

(3) 事实是他不好看。shìshí shì tā bū hǎokàn.

Truth COP he-NOM NEG good-looking.

'The truth is that he is not good-looking.'

English

DP = DP

Equative sentences resemble predicative sentences in that they have two noun phrases and the copular verb ‘to be’. However, the similarity is superficial. Compare the following two sentences:

(4) Cicero is Tully. (5) Cicero is an orator and philosopher.

Analysis of these sentences will show that there is a radical difference between the equative sentence and the predicational sentence in English. The predicational sentence in (5) ascribes the property to the referent noun phrase whereas the equative sentence basically says that the first and second noun phrase share the same referent. It is difficult to distinguish between a predicative and equative sentence in English as both use a similar construction and both require the copular verb ‘to be’. Unlike specificational sentences, truly equative sentences cannot be analyzed as syntactically inverted predications, because neither expression is functioning as a predicate. Note that even English examples like (4) have predicational interpretations, as in a context where Tully is a character in a play, or where Tully refers to the property of being named Tully, rather than referring to the actual referent.

Haitian Creole

DP = DP

In Haitian Creole the equative clause pattern involves the equative copula sé which joins a subject noun phrase with a complement noun phrase that refers back to the subject.

(6) Misyé Pól sé vwézinaj mwen.

Mr. Paul Copula neighbour my

'Mr.Paul is my neighbour'

A simple copula predicate consists of sé 'am/is/are' only. The negative marker pa and the TMA (tense-mood-aspect) markers can co-occur with the copula-type predicate, subject to certain rules (TMA markers: té 'past' or 'anterior', kay 'prospective' or 'irrealis', ka 'nonpunctual', sa 'abilitative'). One such rule is that té + sé → sété (or just té without sé). The combinations permitted in an equative clause are limited in natural speech: a maximum number of two tense, mood, aspect and copula morphemes can co-occur in a given clause.[8] Here are some examples of the equative clause type in Haitian Creole (predicates are in bold):

(7) Ou sé jan mwen. 'You are my friend.'

Ou té jan mwen. 'You were my friend.'

Ou kay jan mwen. 'You will be my friend.'

Ou pa té kay jan mwen. 'You wouldn't be my friend.'

Ou sa jan mwen. 'You can be my friend.'

Ou pa sa jan mwen. 'You cannot be my friend.'

Non mwen sé Tjals. 'My name is Charles.'

Tjals sété an Endyen. 'Charles was an Indian.'

Escure & Schwegler claim that sé is a copula verb. DeGraff [9] argues that sé in Haitian Creole is a resumptive pronominal that spells out the trace produced by subject-raising to Spec (CP) from within a small clause headed by the nominal predicate. The subject is first merged within the (extended) projection of the nominal predicate – i .e., in the subject position of the small clause – but it must move to Spec (СP) in order to check its Case and satisfy the Extended Projection Principle.

Korean

DP = DP

The copula -i- in Korean is ubiquitously found in presumed ‘Sluicing’ and ‘Fragment’ constructions. The copula denotes the equative relation between the subject and the complement of the copula. In (8), through the assumed equative relation, the complement of the copula describes the ‘categorial membership’ of the subject.

(8) a. Chelswu-nun chakhan haksayng-i-ta.

Chelswu-Top kind-hearted student-Cop-Decl

‘Chelswu is a kind-hearted student’

b. hak-un twulwumi-i-ta.

crane-Top crane-Cop-Decl

‘A crane is a crane.’

On top of it, again through the equative relation, in (9) the complement of the copula describes the ‘characteristic property’ of the subject.

(9) a. pangan-i engmang-i-ta.

room-Nom mess-Cop-Decl

‘A room is a mess.’

b. toli-nun cengkwusomssi-ka seykyeycek4-i-ta.

Toli-Top tennis skill-Nom world-class-Cop-Decl

‘Toli is world class in tennis skill.’

DP = CP

When the copula is not present, no equative relation holds, prohibiting the pronominal subject of the small clause. In the former case, the indefinite expression as a correlate expression is equative with the surviving expression. In the latter case, the usual referring expression as a correlate expression cannot be equative with the surviving expression that it is in contrast with.[10] Equative (Identificational) Copular Construction (ECC) as shown in (10), both nominal expressions in the Equative Copular Construction are referential expressions and hence denote individual entities denoted by the two nominal expressions. The construction expresses the identity relation between the entities denoted by the two nominal expressions.

(10) Chelswu-ka [ne-ka ecey ttayli-n salam]-i-ta.

C-Nom you-Nom yesterday hit-Adn person-Cop-Decl

‘Chelswu is the one that you hit yesterday.’

Since the Equative Copular Construction is involved with the two referential nouns, no word order restriction is expected with regard to the focus information.[11]

Non-copular equative constructions

Russian

DP = DP

Russian equative sentences have a distinct syntactical structure which distinguishes them from predicational sentences. They require a constant form of the demonstrative pronoun eto 'this' (Sg. Neutral) to indicate that the two XPs have the same referent.

(11) Mark Twain - *(éto) Samuel Clemens.

Mark Twain. Nom this Samuel Clemens.Nom

Mark Twain is Samuel Clemens

This is because Russian has a zero present form copula (byt’ has no present tense form). The demonstrative pronoun, however, is excluded from predicational sentences. In addition, although Russian has case endings on the ends of nouns, both XPs occur in the Nominative case in an equative sentence but not in a predicational one. The demonstrative pronoun likewise never gets inflected in equative sentences. In order to warrant that XP2 in the Instrumental is excluded from éto-sentence (and not because of lacking an overt copula), we have an overt form of the byt' copula.

(12) Ciceron - éto byl Tullij.

Cicero.Nom this was.Masc Tully.Nom

'Cicero was Tully'

(13) *Ciceron - éto byl Tulliem.

Cicero.Nom this.Neut was.Masc Tully.Ins

'Cicero was Tully'

There is strong evidence that in (12), XP2 is the underlying subject: the copula agrees with XP2 and not with ėto, which remains Singular Neuter. Nominative. Whereas XP1 functions as an external topic, the demonstrative pronoun éto is a base-generated internal topic. [12]

Polish

DP = DP

Polish equatives differ in syntactic structure considerably from predicational and specificational copula classes, with respect to agreement pattern. Polish true equatives contain two nominative DPs (proper names or pronouns), which surround the copula. There are two types of copula: the pronominal copula to, and the verbal copula być 'to be'. Unlike Polish to-predicational clauses in which they are restricted to 3rd person pronouns only, the equatives with pronominal copula to allows the pre-copular element to be in 1st or 2nd person perspective.

(14) a. Ja to ty.

I.NOM COP you.NOM.

‘I am you.’

(15) a. Wy to my.

You.PL.NOM COP we.NOM.

'You are we.' |

Moreover, in Polish equative sentences, the verb always agrees with the pre-copular element. The two copulas can also co-occur with each other. If it is in the present tense, it can always be omitted. If it is omitted in the past or future tense, the time interpretation will be misunderstood as referring to the present only.[13]

(16) a. Ja to (jestem) ty, a ty to (jesteś) ja.

I.NOM COP am you.NOM and you.NOM COP are I.NOM

‘I am you and you are me’

b. Ja to *(byłem) ty

I.NOM COP be.PAST1SG you.NOM

'I was you' |

Polish equatives sometimes involve both the operation of wh-movement and deletion. All instances of unbounded deletion obeying island constraints are instances of wh-movement and deletion. The deletion might apply in conjunction with wh-movement or it might apply alone. When it applies alone, it is both unbounded and subject to island constraints. For instance, in (17), Jak appears in wh-questions, which suggests that the equative shown in (18) involves wh-movement. In (19), deletion applies in conjunction with wh-movement.[14]

(17) a. Jak wysoki jest Jan?"

How tall is John?

(18) a. Jan jest tak wysoki, jak byl Jerzy.

John is so tall how was George

'John is as tall as George was'

(19) a. Maria jest tak piqkna, jak mowilem, ze jest.

Mary is so beautiful how (I) said that (she) is

'Mary is as beautiful as I said she was.' |

Arabic

This description concerns Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). Like Russian and Polish, MSA uses no copular verb in present tense equative sentences but requires one in the past and future. The subject and predicate in MSA equative sentences must agree in case (nominative), number, and gender [15] The subject must always be definite for a sentential reading, while the predicate is definite or indefinite depending on whether an article is also used in the sentence.

The following equation does not involve an article, so the predicate 'the student' is in indefinite form.

(20) samir-un taalib-un

samir-nom student-nom

"Samir (is) a student"

In the following construction, an article interferes between the subject and predicate, so the predicate is in definite form. 3MS means 3rd person masculine singular.

(21) samir-un huwa t-taalib-u

samir-nom 3MS the student-nom

"Samir (is) the student"

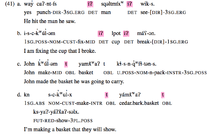

Okanagan Salish

This description concerns the Interior Salish language of the Colville-Okanagan region, named Nsyilxcən. Its classification here as non-copular is due to its lack of an overt copula. Rather, Nsyilxcən equatives are said to be projections of a null head. Nsyilxcən DP-DP structures involve a null, equative copula. The interpretation of DP-DP structures in Nsyilxcən overlaps with that of both predicational and equative clauses in English.[16] The semantics of the equative head fit with intensionality-based accounts of English equatives.[17] The distinction between predicational and equative sentences is motivated by a word order restriction that is for DP-DP structures in answer to WH-questions, which is not apparent for a corresponding direct predication. As well, Nsyilxcən does not have specificational sentences in the classic sense, but it does have DP-DP equatives with a fixed information structure resembling inverse specificational copular clauses in English.[18]

DP = DP

In Nsyilxcən, equatives exhibit a DP=DP structure. As in English, two adjacent DPs standing in an equivalence relationship are interpreted as semantically equative, given that neither DP can be a predicate. This equative has an encoded word order restriction which is absent from predications involving other syntactic categories, such that in answer to a WH-question, a directly referential demonstrative or proper name must precede a DP headed by the determiner "iʔ" (an “iʔ DP”). The implication is that specificational sentences are not possible in Nsyilxcən. [19]

DP = DP Clefts

Nsyilxcən clefts are structurally equivalent to DP=DP structures, implying that clefts are also equatives in this language.

(22) ixíʔ iʔ səxw-m’aʔ-m’áyaʔ-m iʔ kwu qwəl-qwíl-st-s.

DEM DET OCC-RED-teach-MID DET 1SG.ABS RED-speak-(CAUS)-3SG.ERG

a. That’s the teacher that talked to me.

b. That teacher is the one that talked to me.

c. It’s the teacher who talked to me.

The null equative head in Nsyilxcən lexically assigns the syntactic feature ‘F’ to its second (leftmost) argument, which is interpretable as ‘focus’ at the interfaces

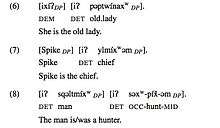

(23) [ixíʔ DP]F = [iʔ pəptwínaxw DP].

DEM = DET old.lady

SHE is the old lady.

(24) *[iʔ pəptwínaxw DP] = [ixíʔDP]F.

DET old.lady = DEM

The old lady is HER.

DP(DP(CP))

Nsyilxcən equatives can also involve relative clause modification. The bracketed, relative clause "iʔ wíkən" ‘that I saw’ restricts the bird under discussion in (36a), and the nominalized relative clause "[iʔ] isck’ʷúl" ‘the (one) that I made’ restricts the type of shirt under discussion in (36b).

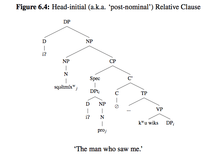

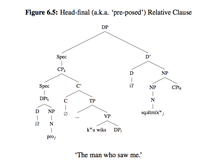

For Nsyilxcən, a relative clause is not identifiable by special inflectional morphology on the clausal modifier, but instead by an "iʔ" determiner and/or "t" marker which precede the modifying head. Relative clause modification can be either head final or head initial.[20] Salish relative clauses can be analyzed based not only on relative head-modifier ordering, but also on whether or not a particle introduces both the head and modifier.[21]

Head initial relative clause |

Head final relative clause |

Chinese

DP = DP

Although Chinese was discussed earlier as having copular equative constructions, it also holds non-copular equative constructions.

(24) a. 他不好看。 tā bù hǎokàn.

He-NOM NEG good-looking.

'He is not good-looking.'

The copular verb 是 shì is often interpreted as having been left out optionally, but this is actually no the case, as the following sentence is ungrammatical:

(25) b. *他是不好看。 tā shì bù hǎokàn.

He-NOM COP NEG good-looking.

*'He is not good-looking.'

For (25b) to be grammatical, the complementizer 的 de is necessary at the end of the adjectival phrase [bù hǎokàn].

Morpheme gloss key

| Abbreviation | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| ABS | Absolutive |

| ACC | Accusative |

| AUX | Auxiliary |

| CAUS | Causative transitivizer |

| COMP | Complementizer |

| CONJ | Conjunction |

| COP | Copula |

| DEM | Demonstrative |

| DET | Determiner |

| NEG | Negation |

| NOM | Nominal |

| OBJ | Object marker |

| OBL | Oblique marker |

| PAST | Past tense |

| PL | Plural |

| POSS | Possessive |

| RED | Reduplicative |

See also

References

- ↑ Heycock, C. (2012). Specification, equation, and agreement in copular sentences. The Canadian Journal of Linguistics/La revue canadienne de linguistique, 57(2), 209-240.

- ↑ Den Dikken, M. (2006). Relators and linkers: The syntax of predication, predicate inversion, and copulas (Vol. 47). MIT Press.

- ↑ Heller, D. (2005). Identity and information: Semantic and pragmatic aspects of specificational sentences (Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey).

- ↑ Adger, D. (2003). Predication and equation. Linguistic Inquiry, 34(3), 325-359. doi:10.1162/002438903322247515

- ↑ Geist, L. (2007). Predication and equation in copular sentences: Russian vs. english. (pp. 79-105). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6197-4_3

- ↑ Halliday, M. A. K. (1968). Notes on transitivity and theme in English Part 3. Journal of linguistics, 4(02), 179-215.

- ↑ Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1995). Outline of Classical Chinese Grammar. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 0-7748-0541-2.

- ↑ Escure, G., & Schwegler, A. (Eds.). (2004). Creoles, contact, and language change: Linguistic and social implications (Vol. 27). John Benjamins Publishing.

- ↑ DeGraff, M. (2007). Kreyòl Ayisyen, or Haitian Creole (Creole French). Comparative Creole Syntax. London: Battlebridge, 101-126.

- ↑ Park, M. K. The syntax of ‘sluicing’/‘fragmenting’in Korean: Evidence from the copula-i-‘be’.

- ↑ Jo, J. M. (2007). Word Order Variations in Korean Copular Constructions. 언어학, 15(3), 209-238.

- ↑ Geist, L. (2007). Predication and equation in copular sentences: Russian vs. english. (pp. 79-105). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6197-4_3

- ↑ Anna Bondaruk, Gréte Dalmi and Alexander Gros (2013) "Polish equatives as symmetrical structures" Copular clauses in English and Polish: Structure, derivation, and interpretation. 61-93.

- ↑ Robert D. Borsley. (Sep., 1981). Wh-Movement" and Unbounded Deletion in Polish Equatives. Journal of Linguistics (Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 271-288). Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/4175592.pdf &acceptTC=true&jpdConfirm=true

- ↑ Abdel-Ghafer, O. (2003). Copular constructions in modern standard Arabic, modern Hebrew and English. ProQuest, UMI Dissertations Publishing.

- ↑ Higgins, F. R. (1973). The Pseudo-cleft Construction In English. Ph. D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA

- ↑ Comorovski, I. (2007). Constituent questions and the copula of specification. In I. Comorovski and K. von Heusinger (Eds.), Existence. Semantics and Syntax, pp. 49–77. Dordrecht: Springer.

- ↑ Lyon, J. (2013). Predication and Equation in Okanagan Salish: The Syntax and Semantics of Determiner Phrases. Ph. D. thesis, The University Of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC

- ↑ Lyon, J. (2013). Predication and Equation in Okanagan Salish: The Syntax and Semantics of Determiner Phrases. Ph. D. thesis, The University Of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC

- ↑ Lyon, J. (2013). Predication and Equation in Okanagan Salish: The Syntax and Semantics of Determiner Phrases. Ph. D. thesis, The University Of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC

- ↑ Davis, H. (2005). Constituency and Coordination in St’át’imcets (Lillooet Salish). In A. Carnie, S. A. Dooley, and H. Harley (Eds.), Verb First: on the Syntax of Verb Initial Languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Further reading

- Benveniste, Emile (1966a) "The Linguistic functions of 'to be' and 'to have' Problems in General linguistics English edition (1970) Miami Linguistics Series 8. University of Miami Press. 163-180.

- Benveniste, Emile (1966b) "The nominal sentence" Problems in General linguistics English edition (1970) Miami Linguistics Series 8. University of Miami Press. 131-144.

- Berman, Ruth and Alexander Grosu (1976) "Aspects of the Copula in Modern Hebrew" in Peter Cole (ed.) Studies in Modern Hebrew Syntax and Semantics The transformational-generative approach. North Holland Publishing Co. Amsterdam. 265-285.

- Carnie, Andrew (1996) Head-Movement and Non-Verbal Predication. Ph.D. Dissertation MIT.

- DeGraff, Michel (1992) "The Syntax of Predication in Haitian" in Proceedings of NELS 22, 103-117. (Distributed by GLSA)

- Doron, Edit (1986) "The Pronominal 'copula' as agreement clitic" The Syntax of Pronominal Clitics, Syntax and Semantics 19 .Academic Press. New York. 313-332.

- Heggie, Lorie (1988) The Syntax of Copular Structures Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Southern California.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1995). Outline of Classical Chinese Grammar. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 0-7748-0541-2.

- Rapoport, Tova (1987) Copular Nominal and Small Clauses Ph.D. Dissertation, MIT

- Rothstein, Susan (1987) "Three forms of English be" MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 9, 225-236.

- Zaring, Laurie (1994) “Two “be” or not two “be” Identity, Predication and the Welsh Copula” Ms. Carlton College.