Émile Bernard

| Émile Bernard | |

|---|---|

_when_painting._Anonymous_photograph_c.1887.jpg) Émile Bernard, part of an anonymous photograph, c. 1892 | |

| Born |

Émile Bernard 28 April 1868 Lille, France |

| Died |

16 April 1941 (aged 72) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Painter |

| Movement | Post-Impressionism; Synthetism; Cloisonnism |

| Patron(s) | Count Antoine de La Rochefoucauld, Andries Bonger, Ambroise Vollard |

Émile Henri Bernard (28 April 1868 – 16 April 1941) was a French Post-Impressionist painter and writer, who had artistic friendships with Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin and Eugène Boch,[1] and at a later time, Paul Cézanne. Most of his notable work was accomplished at a young age, in the years 1886 through 1897. He is also associated with Cloisonnism and Synthetism, two late 19th-century art movements. Less known is Bernard's literary work, comprising plays, poetry, and art criticism as well as art historical statements that contain first hand information on the crucial period of modern art to which Bernard had contributed.

Biography

by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1886)

Émile Henri Bernard was born in Lille, France in 1868. As in his younger years his sister was sick, Émile was unable to receive much attention from his parents; he therefore stayed with his grandmother, who owned a laundry in Lille, employing more than twenty people. She was one of the greatest supporters of his art. The family moved to Paris in 1878, where Émile attended the Collège Sainte-Barbe.

Education

He began his studies at the École des Arts Décoratifs. In 1884, joined the Atelier Cormon where he experimented with impressionism and pointillism and befriended fellow artists Louis Anquetin and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. After being suspended from the École des Beaux-Arts for "showing expressive tendencies in his paintings", he toured Brittany on foot, where he was enamored by the tradition and landscape.

In August 1886, Bernard met Gauguin in Pont-Aven. In this brief meeting, they exchanged little about art, but looked forward to meeting again. Bernard said, looking back on that time, that "my own talent was already fully developed." He believed that his style did play a considerable part in the development of Gauguin's mature style.

1887–1888

Bernard spent September 1887 at the coast, where he painted La Grandmère, a portrait of his grandmother. He continued talking with other painters and started saying good things about Gauguin. Bernard went back to Paris, attended Académie Julian, [2] met with van Gogh, who as we already stated was impressed by his work, found a restaurant to show the work alongside van Gogh, Anquetin, and Toulouse-Lautrec's work at the Avenue Clichy. Van Gogh called the group the School of Petit-Boulevard.

One year later, Bernard set out for Pont-Aven by foot and saw Gauguin. Their friendship and artistic relationship grew strong quickly. By this time Bernard had developed many theories about his artwork and what he wanted it to be. He stated that he had "a desire to [find] an art that would be of the most extreme simplicity and that would be accessible to all, so as not to practice its individuality, but collectively…" Gauguin was impressed by Bernard's ability to verbalize his ideas.

1888 was a seminal year in the history of Modern art. From 23 October until 23 December Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh worked together in Arles. Gauguin had brought his new style from Pont-Aven exemplified in Vision after the Sermon: Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, a powerful work of visual symbolism of which he had already sent a sketch to van Gogh in September.

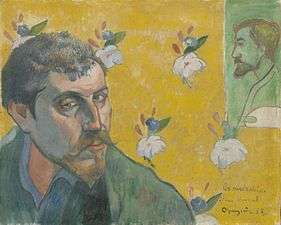

Self-portrait with portrait of Paul Gauguin, Bernard, 1888.

Self-portrait with portrait of Paul Gauguin, Bernard, 1888. Gauguin's counterpiece, same year, for same 'Vincent'.

Gauguin's counterpiece, same year, for same 'Vincent'..jpg) Breton Women in a Green Pasture, Bernard, 1888.

Breton Women in a Green Pasture, Bernard, 1888. Van Gogh's copy, December 1888.

Van Gogh's copy, December 1888. Vision after the Sermon: Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, Gauguin, 1888.

Vision after the Sermon: Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, Gauguin, 1888.

He also brought along Bernard's Le Pardon de Pont-Aven which he had exchanged for one of his paintings and which he used to decorate the shared workshop. see in: (ref. Druick 2001) This work was equally striking and illustrative of the style Émile Bernard had already acquainted van Gogh with when he sent him a batch of drawings in August, so much so that van Gogh made a watercolor copy of the "Pardon" (December 1888) which he sent to his brother, to recommend Bernard's new style to be promoted. The following year van Gogh still vividly remembered the painting in his written portrait of Émile Bernard in a letter to his sister Wil (10 December 1889):"...it was so original I absolutely wanted to have a copy."

Bernard's style was effective and coherent (see:woman at haystacks,) as can also be seen from the comparison of the two "portraits" Bernard and Gauguin sent to van Gogh at the end of September 1888 at the latter's request: self-portraits -at Gauguin's initiative- each integrating a small portrait of the other in the background. (ref. Druick 2001)

One of Émile Bernard's drawings from the August batch ("...a lane of trees near the sea with two women talking in the foreground and some strollers" – Vincent van Gogh in a letter to Bernard – Arles 1888) also appears to have inspired the work van Gogh and Gauguin did on the Allée des Alyscamps in Arles.

In 1891 he joined a group of Symbolist painters that included Odilon Redon and Ferdinand Hodler. In 1893 he started traveling, to Egypt, Spain and Italy and after that his style became more eclectic. He returned to Paris in 1904 and remained there for the remainder of his life. He taught at the École des Beaux-Arts before he died in 1941.

- "[…] this creative, avant-garde young man destroyed himself in a fight against that same avant-garde he had helped to create. His rivalry with Gauguin led him out of spite along a different path: classicism. This change took place when he was living in the Middle East, in a period of great crisis. But the fact remains that the young Bernard played an essential part as an initiator for Gauguin, and that he was the inventor of a new artistic vision."

Theories on style and art: Cloisonnism and Symbolism

Bernard theorized a style of painting with bold forms separated by dark contours which became known as cloisonnism. His work showed geometric tendencies which hinted at influences of Paul Cézanne, and he collaborated with Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh.

Many say that it was Bernard's friend Anquetin, who should receive the credit for this "closisonisme" technique. During the spring of 1887, Bernard and Anquetin "turned against Neo-Impressionism." It is also likely that Bernard was influenced by the works he had seen of Cézanne. But Bernard says "When I was in Brittany, I was inspired by "everything that is superfluous in a spectacle is covering it with reality and occupying our eyes instead of our mind. You have to simplify the spectacle in order to make some sense of it. You have, in a way, to draw its plan."

"The first means that I use is to simplify nature to an extreme point. I reduce the lines only to the main contrasts and I reduce the colors to the seven fundamental colors of the prism. To see a style and not an item. To highlight the abstract sense and not the objective. And the second means were to appeal to the conception and to the memory by extracting yourself from any direct atmosphere. Appeal more to internal memory and conception. There I was expressing myself more, it was me that I was describing, although I was in front of the nature. There was an invisible meaning under the mute shape of exteriority."

Symbolism and religious motifs appear in both Bernard and Gauguin's work. During the summer of 1889, Bernard was alone in Le Pouldu and began to paint many religious canvasses. He was upset that he had to do commercial work at the same time that he wanted to create these pieces. Bernard wrote about his relationship with the style of symbolism in many letters, articles, and statements. He said that it was of a Christian essence, divine language. Bernard believed that it "It is the invisible express by the visible," and those previous attempts of religious symbolism failed. That period of symbolism represented the nature of beauty, but did not find the truth in the beauty. Art until the renaissance was based on the invisible rather than the visible, the idea, not the shapes or concrete. The history of the painting of symbols was spiritual. Everything, meaning symbols, were forgotten with the paganist ideas and doctrines. That is what Bernard was attempting to accomplish with the rebirth of symbolism in 1890. In his idea of the new symbolism, he concentrated on maintaining a grounded art, more authentic in Bernard's mind meant reducing impressionism, not creating an optical trip like Georges-Pierre Seurat, but simplifying the actual symbol.

His concept was that through ideas, not technique, the truth is found.

Influence

It was always Émile Bernard's great frustration that Paul Gauguin never mentioned him as an influence on pictorial symbolism (see for instance his own notes attached to the Belgian edition (1942) of his selected letters, published shortly after his death). In 2001/2002 The Art Institute of Chicago and the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam held a joint exhibition:Van Gogh and Gauguin:The Workshop of the South that put Émile Bernard's contribution in perspective. (ref. Druick 2001)

One of Émile Bernard's students was the Swedish painter Ivan Aguéli.

Works

- Yellow Tree, 1888.

Brothel scene, sent+dedicated to Vincent van Gogh, 1888.

Brothel scene, sent+dedicated to Vincent van Gogh, 1888.- Émile Bernard, Portrait of a Boy in Hat, 1889.

Still life with teapot, cup and fruit, 1890.

Still life with teapot, cup and fruit, 1890. Breton Peasants in a Meadow, 1892.

Breton Peasants in a Meadow, 1892.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Émile Bernard. |

Writings

Art criticism

- Au Palais des Beaux-Arts. Notes sur la peinture

- Le Moderniste I/14, 27 July 1889, pp. 108 and 110

- Paul Cézanne

- Les Hommes d'aujourd'hui, no. 387

- Vincent van Gogh

- Les Hommes d'aujourd'hui, no. 390, (1891)

- reprinted in: Lettres & Recueil (1911), pp. 65–69

- Néo-traditionnistes: Vincent van Gogh

- La Plume III/57, 1 September 1891, pp. 300–301

- Charles Filliger (!)

- La Plume III/64, 15 December 1891, p. 447

- Vincent van Gogh[3]

- Mercure de France VII/40, April 1893, pp. 324–330

- reprinted in: Lettres & Recueil (1911), pp. 45–52

- Note

- Mercure de France VII/44, August 1893, pp. 303–305

- reprinted in: Lettres & Recueil (1911), pp. 53–57

- Avant-propos pour le premier volume de la correspondance de Vincent

- dated 10 June 1895

- first published in: Lettres & Recueil (1911), pp. 59–63

- Notes sur l'école dite de "Pont-Aven"

- Mercure de France XLVIII, December 1903, pp. 675–682

- Julien Tanguy dit le "Père Tanguy"

- Mercure de France LXXVI/276, 16 December 1908, pp. 600–616

- Preface

- Lettres de Vincent van Gogh à Émile Bernard & Recueil des publications sur Vincent van Gogh faites depuis son déces par Émile Bernard, précédées d'une preface nouvelle par le même auteur, Ambroise Vollard, éditeur, Paris, 1911, pp. 1–43

- La méthode de Paul Cézanne. Exposé critique

- Mercure de France CXXXVIII/521, 1 March 1920, pp. 289–318

- Une conversation avec Cézanne

- Mercure de France CXLVIII/551, 1 June 1921, pp. 372–397

- Souvenirs sur Van Gogh

- L'Amour de l'Art, December 1924, pp. 393–400

- Souvenirs sur Paul Cézanne: une conversation avec Cézanne, la méthode de Cézanne. Paris: Chez Michel, 1925.

- Louis Anquetin

- Gazette des Beaux-Arts VI/11, February 1934, pp. 108–121

- Le Symbolisme pictural, 1886–1936

- Mercure de France CCLXVIII/912, 15 June 1936, pp. 514–530

- Souvenirs inédits sur l'artiste peintre Paul Gauguin et ses compagnons lors de leur séjour à Pont-Aven et au Pouldu

- Nouvelliste du Morbihan, Lorient, (1939)

- Note relative au Symbolisme pictural de 1888–1890

- first published in:

- reprinted in: Lettres à Émile Bernard, Editions de la Nouvelle Revue Belgique, Brussels 1942, pp. 241–257

Letters

His correspondence with other artists is of great art historical interest. Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Bernard traded ideas and art. Many letters sent from van Gogh and Gauguin to Bernard give historians a better idea of the artists lives and connection to their artwork.

- Lettres à Émile Bernard de Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Odilon Redon, Paul Cézanne, Elémir Bourges, Léon Bloy, G. Apollinaire, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Henry de Groux, Editions de la Nouvelle Revue Belgique, Brussels 1942

- Neil McWilliam (ed.), "Émile Bernard. Les Lettres d'un artiste (1884-1941)", Les Presses du réel, Dijon, 2012, an edited selection of 430 letters covering the entirety of the artist's career.

Notes, references and sources

- Notes and references

- ↑ http://www.eugeneboch.com Eugène Boch a common friend of Vincent van Gogh and Émile Bernard

- ↑ Russell, John. "An Art School That Also Taught Life," New York Times. 19 March 1989

- ↑ This text and the Note following accompanied excerpts from Vincent van Gogh's letters to Bernard and to Theo, his brother, published in the Mercure de France 1893 through 1897. Translated to the German by Margarethe Mauthner, this selection was pre-published by Bruno Cassirer in Kunst und Künstler, Berlin, June 1904 to September 1905, and finally in a bestselling volume.

- Sources

- Alley, Ronald. The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 133, No. 1056 (Mar. 1991)

- Dorra, Henri: Émile Bernard and Paul Gauguin, Gazette des Beaux-Arts 1955. Vol. 45.

- Druick, Douglas W., and Seghers, Peter Kort: Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Workshop of the South – Art Institute of Chicago Museum Shop, Paperback, 2001

- Leeman, Fred: Émile Bernard (1868 - 1941), Citadelles & Mazenod editors; Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2013, 495 p. ISBN 9782850885716

- Luthi, Jean-Jacques: Émile Bernard, Catalogue raisonné de l'œuvre peint, Editions SIDE, Paris 1982 ISBN 2-86698-000-X

- McWilliam, Neil; Karp-Lugo, Laura, and Welsh-Ovcharov, Bogomila: "Émile Bernard. Au-delà de Pont-Aven", Institut national d'histoire de l'art, Paris, 2012

- Morane, Daniel: Émile Bernard 1868–1941, Catalogue de l'œuvre gravé, Musée de Pont-Aven & Bibliothèque d'Art et d'Archéologie – Jacques Doucet, Paris, 2000 ISBN 2-910128-20-2

- Stevens, MaryAnne, et alt.: Émile Bernard 1868–1941, a pioneer of Modern Art / Ein Wegbereiter der Moderne, Waanders, Zwolle 1990 ISBN 90-6630-151-1

- Waschek, Matthias: Eklektizismus und Originalität. Die Grundlagen des französischen Symbolismus am Beispiel von Émile Bernard, PhD Bonn 1990 ISBN 3-89191-342-7

- Welsh-Ovcharov, Bogomila: Vincent van Gogh and the Birth of Cloisonism, Toronto & Amsterdam, 1980

External links

- Signac, 1863-1935, a fully digitized exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries, which contains material on Bernard (see index)

- artcyclopedia.com

- Van Gogh Letters to Bernard, The Morgan Library online exhibition (facsimiles and translations).

- Émile Bernard in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website