Emblem of Italy

| Emblem of Italy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Armiger | Italian Republic |

| Adopted | 5 May 1948 |

| Escutcheon | Stella d’Italia |

| Supporters | Olive and Oak |

| Motto | REPVBBLICA ITALIANA |

The emblem of Italy (Italian: emblema della Repubblica Italiana) was formally adopted by the newly formed Italian Republic on 5 May 1948. Although often referred to as a coat of arms (or stemma in Italian), it is technically an emblem as it was not designed to conform to traditional heraldic rules. The emblem comprises a white five-pointed star, with a thin red border, superimposed upon a five-spoked cogwheel, standing between an olive branch to the dexter side and an oak branch to the sinister side; the branches are in turn bound together by a red ribbon with the inscription REPVBBLICA ITALIANA. The emblem is used extensively by the Italian government.

The armorial bearings of the House of Savoy, blazoned gules a cross argent, were previously in use by the former Kingdom of Italy; the supporters, on either side a lion rampant Or, were replaced with fasci littori (literally bundles of the lictors) during the fascist era.

Kingdom of Italy

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Between 1848 and 1861, a sequence of events led to the independence and unification of Italy (except for Venetia, Rome, Trento and Trieste, or Italia irredenta, which were united with the rest of Italy in 1866, 1870 and 1918 respectively); this period of Italian history is known as the Risorgimento, or resurgence. During this period, the green, white and red tricolore became the symbol which united all the efforts of the Italian people towards freedom and independence.[1]

The Italian tricolour, defaced with the coat of arms of the House of Savoy, was first adopted as war flag by the Regno di Sardegna-Piemonte (Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont) army in 1848. In his Proclamation to the Lombard-Venetian people, Charles Albert said "… in order to show more clearly with exterior signs the commitment to Italian unification, We want that Our troops … have the Savoy shield placed on the Italian tricolour flag."[2] As the arms mixed with the white of the flag, it was fimbriated azure, blue being the dynastic colour.[3] On 15 April 1861, when the Regno delle Due Sicilie (Kingdom of the Two Sicilies) was incorporated into the Regno d'Italia, after defeat in the Expedition of the Thousand led by Giuseppe Garibaldi, this flag and the armorial bearings of Sardinia were declared the symbols of the newly formed kingdom.

.svg.png)

On 4 May 1870, nine years later, the Consulta Araldica issued a decree on the arms, as with the Sardinian arms, two lions rampant in gold supporting the shield, bearing instead only the Savoy cross (as on the flag) now representing all Italy, with a crowned helmet, around which, the collars of the Military Order of Savoy, the Civil Order of Savoy, the Order of the Crown of Italy (established 2 February 1868), the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, and the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation (bearing the motto FERT) were suspended. The lions held lances flying the national flag. From the helmet fell a royal mantle, engulfed by a pavilion under the Stellone d'Italia, purported to protect the nation.[4]

After twenty years, on 1 January 1890, the arms' exterior were slightly modified more in keeping with those of Sardinia. The fur mantling and lances disappeared and the crown was taken from the helmet to the pavilion, now sewn with crosses and roses. The Iron Crown of Lombardy was placed on the helmet, under the traditional Savoyan crest (a winged lionhead), which, together with the banner of Savoy from the former Sardinian arms, replaced the star of Italy.[5] These arms remained in official use for 56 years until the birth of the Italian Republic and continue today as the dynastic arms of the head of the House of Savoy.[6] On 11 April 1929, the Savoy lions were replaced by Mussolini with fasces from the National Fascist Party shield.[7] After his dismissal and arrest on 25 July 1943 however, the earlier version was briefly restored until the emblem of the new Repubblica Italiana was adopted, after the institutional referendum on the form of the state, held on 2 June 1946. This is celebrated in Italy as Festa della Repubblica.

Italian Social Republic

The arms of the short-lived Nazi state in northern Italy, the Repubblica Sociale Italiana (Italian Social Republic), or Republic of Salò as it was commonly known, was that of the governing Republican Fascist Party, a silver eagle clutching a banner of the tricolore inverted on a shield charged with fasces.[8] Italian fascism derived its name from the fasces, which symbolises authority and/or "strength through unity". The fasces has been used to show the imperium (power) of the Roman Empire, and was thus considered an appropriate heraldic symbol. Additionally, Roman legions had carried the aquila, or eagle, as signa militaria.

This shield had previously been displayed alongside the Royal arms from 1927 to 1929, when the latter was modified to incorporate elements of both.[9]

On 25 April 1945, commemorated as Festa della Liberazione, the government of Benito Mussolini fell. The separate Italian Social Republic had existed for slightly more than one and a half years.

Italian Republic

The decision to provide the new Italian Republic with an emblem was taken by the government of Alcide De Gasperi in October 1946. The design was chosen by public competition, with the requirement that party political emblems were forbidden and the inclusion of the Stellone d'Italia, "inspired by a sense of the earth and municipalities." The five winners were assigned further requirements for the design of the emblem, "a ring that has towered shaped crown," surrounded by a garland of Italian foliage and flora. Below a representation of the sea, and above, the gold star, with the legend Unità e Libertà or Unity and Liberty in the Italian language. The winner was Paolo Paschetto, Professor of the Institute of Fine Arts in Rome from 1914 to 1948, and the design was presented in February 1947, together with the other finalists, in an exhibition in Via Margutta. This version, however, did not meet with public approval, so a new competition was held, again won by Paolo Paschetto. The new emblem was approved by the Constituent Assembly in February 1948, and officially adopted by the President of the Italian Republic, Enrico De Nicola in May 1948.[10]

Description

The emblem comprises a white five-pointed star, with a fine red border, superimposed upon a five-spoked cogwheel, between an olive branch on the left, and an oak branch on the right side; the green branches are in turn bound together by a red ribbon bearing the inscription REPVBBLICA ITALIANA in white capital letters. As it was not designed to conform to traditional heraldic rules, it does not have a formal blazon.[11] The dominant element, however, is the five-pointed Stellone d'Italia; an ancient secular symbol of Italy. Iconographic of the Risorgimento, it is usually seen shining radiant over Italia Turrita, the personification of Italy. The star marked the first award of Republican reconstruction, the Order of the Star of Italian Solidarity, and still indicates membership of the Armed Forces today. The steel cogwheel which surrounds it refers to the Constitution of the Italian Republic:—

Italy is a democratic republic, built on labour. [...]

At the top, its shape also recalls a mural crown, as worn by Italia Turrita (meaning with towers), typical of Italian civic heraldry of communal origin. Both oak and olive trees are characteristic of the Italian landscape. While the oak branch is symbolic of the strength and dignity of the Italian people, the olive branch represents the Republic’s desire for peace, both harmony at home and brotherhood abroad, as expressed in the Constitution:—

Italy repudiates war as an instrument of aggression [...]

Elements of the emblem, such as its industrial symbolism and star, are influenced by socialist heraldry.[12]

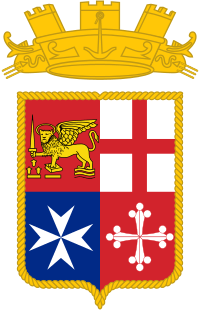

Armed forces

The Italian naval ensign, since 1947, comprises the national flag defaced with the arms of the Marina Militare; the Marina Mercantile (and private citizens at sea) use the civil ensign, differenced by the absence of the mural crown and the lion holding open the gospel, bearing the inscription PAX TIBI MARCE EVANGELISTA MEVS, instead of a sword.[13] The shield is quartered, symbolic of the four repubbliche marinare, or great thalassocracies, of Italy: Venice (represented by the lion passant, top left), Genoa (top right), Amalfi (bottom left), and Pisa (represented by their respective crosses). To acknowledge the Navy's origins in ancient Rome, the rostrata crown, "... emblem of honor and of value that the Roman Senate conferred on duci of shipping companies, conquerors of lands and cities overseas," was proposed by Admiral Cavagnari in 1939. An inescutcheon, bearing the Savoy shield flanked by fasces, was removed before the arms were first employed.[14]

The Esercito Italiano, Aeronautica Militare and Arma dei Carabinieri also have their own distinctive coats of arms as do each of the municipalities, provinces and regions of Italy.

See also

References

- ↑ Ghisi, Enrico Il tricolore italiano (1796-1870) Milano: Anonima per l'Arte della Stampa, 1931; see Gay, H. Nelson in The American Historical Review Vol. 37 No. 4 (pp. 750-751), July 1932

- ↑ "Per viemmeglio dimostrare con segni esteriori il sentimento dell'unione italiana vogliamo che le Nostre truppe ... portino lo scudo di Savoia sovrapposto alla bandiera tricolore italiana." See Lawrence, D.H. (ed. Philip Crumpton) Movements in European History (p. 230) Cambridge University Press, 1989 for an overview

- ↑ Lo Statuto Albertino Art. 77, dato in Torino addì quattro del mese di marzo l'anno del Signore mille ottocento quarantotto, e del Regno Nostro il decimo ottavo

- ↑ Deliberazione della Consulta Araldica del Regno d’Italia con cui si determina quali debbano essere gli ornamenti esteriori dello stemma dello Stato, 4 maggio 1870; Regio Decreto n. 7282 del 27 novembre 1890

- ↑ Armi della Real Casa d'Italia Corpo della Nobiltà Italiana; Gli stemmi della Famiglia Reale sono regolati dal relativo Regio Decreto del 1 gennaio 1890 e gli stemmi dello Stato e delle Amministrazioni governative sono regolati dal Regio Decreto del 27 novembre 1890

- ↑ Compiti, Prerogative e Responsabilità del Capo di Casa Savoia nell'Italia Repubblicana Reale Casa d'Italia (retrieved 24 January 2009)

- ↑ Regio Decreto n. 504 del 11 aprile 1929 VII

- ↑ Foggia della bandiera nazionale e della bandiera di combattimento delle Forze Armate Decreto Legislativo del Duce della Repubblica Sociale Italiana e Capo del Governo n. 141 del 28 gennaio 1944 XXII EF (GU 107 del 6 maggio 1944 XXII EF)

- ↑ Regio Decreto n. 2061 del 12 dicembre 1926 sull'emblema del Fascio Littorio, Regio Decreto Legislativo n. 2273 del 30 dicembre 1926 norme per la fabbricazione, distribuzione e vendita di insegne e distintivi portanti l'emblema del Fascio Littorio, Regio Decreto n. 1048 del 27 marzo 1927 disposizioni circa l'uso del Fascio Littorio da parte delle Amministrazioni dello Stato, Legge n. 928 del 9 giugno 1927 conversione in legge del R. D.-L. 12 dicembre 1926, che dichiara il Fascio Littorio emblema dello Stato (GU 160 del 13 luglio 1927)

- ↑ Foggia ed uso dell'emblema dello Stato Decreto Legislativo n. 535 del 5 maggio 1948, pubblicato nella Gazzetta Ufficiale n. 122 del 28 maggio 1948 suppl. ord.

- ↑ Disposition XIV of the Italian Constitution provides that "The law shall regulate the suppression of the Heraldic Council"

- ↑ von Volborth, Carl-Alexander (1983). Heraldry: Customs, Rules and Styles. Ware, Hertfordshire: Omega Books Ltd. p. 11. ISBN 0-907853-47-1.

- ↑ Decreto Legislativo del capo provvisorio dello stato n. 1305 del 9 novembre 1947 (GU 275 del 29 novembre 1947)

- ↑ "Emblema di onore e di valore che il Senato romano conferiva ai duci di imprese navali, conquistatori di terre e città oltremare;" La Bandiera della Marina Militare Ministero della Difesa (retrieved 5 October 2008)

External links

Media related to Coats of arms of Italy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Coats of arms of Italy at Wikimedia Commons- Un simbolo per la Repubblica Presidenza della Repubblica, Palazzo del Quirinale (Italian)

- Italian Civic Heraldry International Civic Heraldry, Ralf Hartemink (English)