Emanuel K. Love

| Emanuel K. Love | |

|---|---|

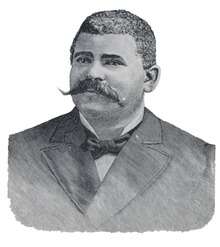

Love in 1888 | |

| Born |

July 27, 1850 Perry County, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died |

April 24, 1900 (aged 49) Savannah, Georgia, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Augusta Institute |

| Occupation | Minister |

| Political party | Republican |

| Religion | Baptist |

Emanuel K. Love (July 27, 1850 – April 24, 1900) was a minister and leader in the Baptist church from Savannah, Georgia. He was pastor of one of the largest churches in the country and was a prominent activist for black civil rights and anti-lynching laws. He played an important role in establishing separate black Baptist national organizations and advocating for black leadership of Baptist institutions, especially schools.

Early life

Love was born a slave on July 27, 1850 near Marion, Alabama in Perry County. He was largely uneducated and worked on a farm until 1870 when he entered Lincoln University in Marion where he studied until 1872. He returned to farm work that year and November 17, 1872 he enrolled in the Augusta Institute in Augusta, Georgia under Reverend Joseph T. Robert. On December 12, 1875 he was ordained in the Baptist church. He graduated in 1877 and was appointed missionary for the state of Georgia by the American Baptist Home Mission Society of New York and the Georgia Mission Society. On July 1, 1879 he resigned to take charge of the First Baptist Church in Thomasville, Georgia. He resigned this post and returned to the position of missionary for the State on October 1, 1881, this time under the auspices of the American Baptist Publication Society. On October 1, 1885 he resigned to accept another charge, pastor to the First African Baptist Church in Savannah, Georgia. This church was one of the largest churches in the world at that time. About that time, he was appointed editor of the Centennial Record and the Georgia Sentinel a Baptist journal and a Baptist Newspaper.[1]

Black separatism in Baptist leadership

In the 1880s American Baptist leadership was dominated by white, segregationist leaders. Love saw this as unjust, and pushed for more publication of racial issues by the American Baptist Publication Society, and proposed a separate black Baptist publication group.[2] In the late 1880s, Love and William J. White were leaders in the separatist factions and called for greater representation of black leaders in Baptist organizations, as well as for black presidents at the Atlanta Baptist College and Spelman College and more representation in the boards of trustees of the schools.[3] In 1887, Love, White, and James C. Bryan were noted for calling for black leadership at the Atlanta Baptist Seminary.[4]

Love's outspokenness led to his promotion to official leadership within the black Baptist church. In 1888, Love was elected president of the colored Baptist Foreign Mission convention in Nashville, Tennessee. Rev. M. W. Gilbert of Nashville was elected vice president, J. J. Spellman of Jackson, Mississippi secretary and J. E. Farrier of Richmond, Virginia treasurer.[5] Also in 1888, Love was among the leaders of a group of 350 leading black Georgians met to push for education legislation and to opposed discrimination, particularly in chain gangs, Jim Crow laws on public transportation, lynch law, disenfranchisement, and jury selection.[6] That year, he published a history of black Baptist churches in America.[7]

Baxley affair

In Thomasville and Savannah in the late 1870s and the 1880s, Love was lauded by the white Baptist community for his work. This support did not extend to the broader white community, nor did it continue in the late 1880s. In 1889, he was among a delgation to travel from Georgia to attend the annual meeting of the black Baptist Foreign Mission Convention in Indianapolis. The train on the East Tennessee, Virginia, and Georgia Railroad had only a first-class car and a smoking car. The delegates opposed smoking and drinking and desired to sit in a first-class car. They had been promised that a segregated first-class car would be provided, but it was not, and the black men found seats for themselves in the white first-class car. White passengers and rail conductors were unhappy and sent a telegram down the line informing people about the infraction. A black porter notified Love about the spread of the news, and once the train stopped at the next stop in Baxley, Georgia, a mob boarded the train and demanded the delegation leave. When they refused, they were attacked and beaten and Love believed that they would have been killed without the interference of the conductor. Five of the delegates including Love and Rev. C. K. Spratling pushed on and went to Indianapolis. They also published an article describing the event which was republished widely.[8]

At the convention, Love was elected president and Solomon T. Clanton, J. E. Jones, and J. E. Farrer officers while vice presidents were selected from the various states. A committee of nearly twenty men were selected to go to Washington and demand protection for blacks in the South taking special notice of the attack on Love and Spratling.[9] The Convention also succeeded at pressuring the American Baptist Publication Society to promise to publish articles by black leaders Walter H. Brooks, William J. Simmons, and Love in its journal, the Baptist Teacher. When white leaders in the society reneged on this promise, the group organized the National Baptist Publishing Board to publish the writings of black Baptist leaders.[10] American Baptist Publication Society leader Benjamin Griffith claimed that no affront was intended and endeavored to expand black representation in the society and in its publications.[11] For their outspokenness, Love and the two others were forced out of the American Baptist Publication Board in 1889.[12]

Conflicts in the 1890s

In 1890, Love and Richard R. Wright, Sr. were in a dispute with William White, Judson Lyons, Henry Rucker, and especially John H. Deveaux, who was in control of Georgia's African American Republic Party machinery. The dispute centered around leadership of the party district nomination conventions. Lyons, Rucker, and Deveaux were all supported by patronage of Booker T. Washington of the Tuskegee Institute and were identified with light-skinned elites, while Love and Wright (and Charles T. Walker) represented a "black" or "darker-skinned" faction, although skin color was not as important as political allegiance and ideology.[13] Dispute within the Baptist church continued as well, and by 1890, Love and Bryan were calling for blacks to stop participating in the American Baptist Missionary Society's educational programs, although White was more friendly, and in 1892, the dispute led to separatism at the state convention.[4]

In 1893, a group within Love's congregation at the First African Baptist Church in Savannah sought to remove Love. They made several charges of immorality against him, but were unable to establish their case.[14] At the 1893 black state Baptist convention, cooperationists supported Charles T. Walker for president of the group while separatists supported Love. The accusations against Love complicated the issue, but he still won the election.[4] As a result of the conflict within his church, about 1,000 members left to form another branch - since the total size of the congregation was as many as 5,000, this did not cripple the church.[15] About this time William E. Holmes, before an opponent of Love and White, changed his position and supported the separatist cause.[3]

Love's leadership in the church continued, however. In 1895, he was corresponding secretary of the Colored Baptist Foreign Mission Convention, with E. C. Morris president and S. T. Clanton and J. L. Dart as fellow officers.[16] In 1896, Love was president of the separatist General Missionary Baptist Convention and continued to advocate black decision makers in prominent positions, especially in leadership of schools for black students. However, he was no longer in accord with William White. White was working with American Baptist Home Missionary Society secretary, Thomas J. Morgan, to repair the strains, but their work only further alienated Love, who was becoming increasingly supportive of black nationalism.[17] In 1897, White was editor of the Georgia Baptist and succeeded in isolating Love in Love's call for a separate, black Baptist college, although Love did succeed in gaining support for the Publishing Board of the National Baptist Convention.[4]

Republican politics

In 1896, Alfred Eliab Buck was the leader of the Georgia Republican Party. Buck was the president of the Republican State Convention in late April and presided over the electing of delegates to the 1896 Republican National Convention. There was dispute over the delegates, which Buck attempted to preempt by passing a "harmony" slate of delegates outside of standard procedure - Love would call it a "lilly white" slate, although it did include blacks. However, the slate did not include Love's friend, Richard R. Wright Sr., who many believed would be a delegate. The convention erupted in protest and a representative of Buck's attempted to adjourn the meeting and the Buck faction left the hall. The Love and Wright faction remained and Love took the chair, electing a new slate of delegates, now including Love (and Buck but still not Wright).[18] Eventually Wright was not selected as a delegate, but did attend as an alternate.[19]

Other activities

Love's work in Georgia was widespread. He wrote or edited three Baptist journals: the Centennial Record, the Georgia Sentinel, and the Baptist Truth as well as two secular papers, the Augusta Weekly Sentinel and the Albany Watchman.[2] The Augusta Sentinel Newspaper was a Republican paper cofounded by Richard R. Wright St, Rev. Charles T. Walker, and Love. Love later pushed to have Wright installed as president of Georgia's first black college.[20] As a part of his journalism, he helped found the publication group for the black National Baptist Convention. He was also president of the Missionary Baptist Convention of Georgia and together with William E. Holmes, was instrumental in founding the Baptist school, Central City College in Macon, Georgia.[12][21] He strongly condemned violence against blacks and many of his sermons were reprinted and widely distributed. One example of both was the November 5, 1893, "Sermon on Lunch Law and Raping".[2]

At the time of his death in 1900, Love was editor of the Baptist Truth, president of the Baptist Missionary Society, and treasurer of Central City College at Macon. He was chairman of the committee which secured the Georgia State Industrial College for Colored Youth for Savannah, now called Savannah State University. He was also a freemason.[15]

Death

Love died April 24, 1900. His funeral was at the First African Baptist church, where he was pastor, and he was buried at Laurel Grove cemetery.[15]

References

- ↑ Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. GM Rewell & Company, 1887. p481-483

- 1 2 3 McCaskill, Barbara, "Savannah's Colored Tribune, the Reverend E. K. Love, and the Sacred Rebellion of Uplift" in eds. McCaskill, Barbara, and Caroline Gebhard. Post-bellum, pre-Harlem: African American literature and culture, 1877-1919. NYU Press, 2006. p101-114

- 1 2 Davis, Leroy. A clashing of the soul: John Hope and the dilemma of African American leadership and Black higher education in the early twentieth century. University of Georgia Press, 1998. p132-133

- 1 2 3 4 Montgomery, William E. Under their own vine and fig tree: The African-American church in the South, 1865-1900. LSU Press, 1995. p246-248

- ↑ Nashville, Tenn. The Times Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) September 22, 1888 page 2, accessed October 17, 2016 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/7063806/nashville_tenn_the_times_democrat/

- ↑ Washington, James Melfin, "The Making of a Church with the Soul of a Nation, 1880-1889" in eds. West, Cornel, and Eddie S. Glaude, eds. African American religious thought: An anthology. Westminster John Knox Press, 2003. p423

- ↑ Love, Emanuel King. History of the First African Baptist Church, from Its Organization, January 10th, 1788, to July 1st, 1888: Including the Centennial Celebration, Addresses, Sermons, Etc. Morning news print, 1888.

- ↑ Remillard, Arthur. Southern civil religions: imagining the good society in the post-Reconstruction Era. University of Georgia Press, 2011. p60-62

- ↑ Colored Baptist Missionaries, The Indianapolis News (Indianapolis, Indiana) September 13, 1889, page 1, accessed September 17, 2016 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/7063958//

- ↑ Montgomery, William E. Under their own vine and fig tree: The African-American church in the South, 1865-1900. LSU Press, 1995. p242-243

- ↑ Harvey, Paul. Redeeming the South: religious cultures and racial identities among Southern Baptists, 1865-1925. Univ of North Carolina Press, 2000. p70-71

- 1 2 Grant, Donald Lee. The way it was in the South: The Black experience in Georgia. University of Georgia Press, 1993. p270

- ↑ Dittmer, John. Black Georgia in the Progressive Era, 1900-1920. University of Illinois Press, 1980. p92-93

- ↑ The Pastor's Game of Freeze-Out, The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia) April 17, 1893, page 3, accessed October 17, 2016 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/7064357/the_pastors_game_of_freezeout_the/

- 1 2 3 Death of Rev. E. K. Love, The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia) April 28, 1900, page 3, accessed October 17, 2016 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/7065177/death_of_rev_e_k_love_the_atlanta/

- ↑ A Huge Assembly, The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia), September 26, 1895 page 5, accessed October 17, 2016 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/7064451/a_huge_assembly_the_atlanta/

- ↑ Oltman, Adele. Sacred Mission, Worldly Ambition: Black Christian Nationalism in the Age of Jim Crow. University of Georgia Press, 2010. p119-122

- ↑ Shadgett, Olive Hall. The Republican Party in Georgia: From Reconstruction Through 1900. University of Georgia Press, 2010. p133-134

- ↑ Republican national convention, St. Louis, June 16th to 18th, 1896. With a history of the Republican party and a survey of national politics since the party's foundation, etc., etc, Republican National Convention (11th : 1896 : Saint Louis, Mo.), page 179, accessed October 17, 2016 at https://archive.org/stream/republicannation00repurich#page/178/mode/2up

- ↑ Billingsley, Andrew. Mighty like a river: The Black church and social reform. Oxford University Press, 1999. p40-44

- ↑ Central City College, later called Georgia Baptist College, closed in 1956