Edith Cavell

| Edith Cavell | |

|---|---|

|

Edith Cavell | |

| Born |

4 December 1865 Swardeston, Norfolk, England |

| Died |

12 October 1915 (aged 49) Tir national (National Shooting Range), Schaerbeek, Brussels, Belgium |

| Venerated in | Church of England |

| Feast | 12 October (Anglican memorial day) |

Edith Louisa Cavell (/ˈkævəl/; 4 December 1865 – 12 October 1915) was a British nurse. She is celebrated for saving the lives of soldiers from both sides without discrimination and in helping some 200 Allied soldiers escape from German-occupied Belgium during the First World War, for which she was arrested. She was accused of treason, found guilty by a court-martial and sentenced to death. Despite international pressure for mercy, she was shot by a German firing squad. Her execution received worldwide condemnation and extensive press coverage.

She is well known for her statement that "patriotism is not enough". Her strong Anglican beliefs propelled her to help all those who needed it, both German and Allied soldiers. She was quoted as saying, "I can’t stop while there are lives to be saved."[1] The Church of England commemorates her in their Calendar of Saints on 12 October.

Edith Cavell, who was 49 at the time of her execution, was already notable as a pioneer of modern nursing in Belgium.

Early life and career

Edith Cavell was born on 4 December 1865[2] in Swardeston, a village near Norwich, where her father was vicar for 45 years.[3] She was the eldest of the four children of the Reverend Frederick and Louisa Sophia Cavell, and was taught always to share with the less fortunate, despite her family’s meagre income.[2] She was educated at Norwich High School for Girls. After a period as a governess, including for a family in Brussels 1890–1895, she trained as a nurse at the London Hospital under Matron Eva Luckes and worked in various hospitals in England, including Shoreditch Infirmary (since renamed St Leonard's Hospital). In 1907, Cavell was recruited by Dr Antoine Depage to be matron of a newly established nursing school, L'École Belge d’Infirmières Diplômées, (or The Berkendael Medical Institute) on the Rue de la Culture (now Rue Franz Merjay), Ixelles in Brussels.[1] By 1910, "Miss Cavell 'felt that the profession of nursing had gained sufficient foothold in Belgium to warrant the publishing of a professional journal' and, therefore, launched the nursing journal, L'infirmière".[1] A year later, she was a training nurse for three hospitals, 24 schools, and 13 kindergartens in Belgium.

When the First World War broke out, she was visiting her widowed mother in Norfolk in the East of England. She returned to Brussels, where her clinic and nursing school were taken over by the Red Cross.

First World War and execution

In November 1914, after the German occupation of Brussels, Cavell began sheltering British soldiers and funnelling them out of occupied Belgium to the neutral Netherlands. Wounded British and French soldiers as well as Belgian and French civilians of military age were hidden from the Germans and provided with false papers by Prince Reginald de Croy at his château of Bellignies near Mons. From there, they were conducted by various guides to the houses of Cavell, Louis Séverin and others in Brussels; where their hosts would furnish them with money to reach the Dutch frontier and provide them with guides obtained through Philippe Baucq.[4] This placed Cavell in violation of German military law.[3][5] German authorities became increasingly suspicious of the nurse's actions, which were further fuelled by her outspokenness.[3]

She was arrested on 3 August 1915 and charged with harbouring Allied soldiers. She had been betrayed by Gaston Quien, who was later convicted by a French court as a collaborator.[6][7] She was held in Saint-Gilles prison for ten weeks, the last two of which were spent in solitary confinement.[3] She made three depositions to the German police (on 8, 18 and 22 August), admitting that she had been instrumental in conveying about 60 British and 15 French soldiers as well as about 100 French and Belgian civilians of military age to the frontier and had sheltered most of them in her house.[4]

In her court-martial she was prosecuted for aiding British and French soldiers, in addition to young Belgian men, to cross the border and eventually enter Britain. She admitted her guilt when she signed a statement the day before the trial. Cavell declared that the soldiers she had helped escape thanked her in writing when they arrived safely in Britain. This admission confirmed that Cavell had helped the soldiers navigate the Dutch frontier, but it also established that she helped them escape to a country at war with Germany.[8]

The penalty according to German military law was death. Paragraph 58 of the German Military Code said that guilty parties; "Will be sentenced to death for treason any person who, with the intention of helping the hostile Power, or of causing harm to the German or allied troops, is guilty of one of the crimes of paragraph 90 of the German Penal Code."[8] The case referred to in the above-mentioned paragraph 90 consists of "Conducting soldiers to the enemy", although this was not traditionally punishable by death. [8] Additionally, the penalties according to paragraph 160 of the German Code, in case of war, apply to foreigners as well as Germans.

While the First Geneva Convention ordinarily guaranteed protection of medical personnel, that protection was forfeit if used as cover for any belligerent action. This forfeiture is expressed in article 7 of the 1906 version of the Convention, which was the version in force at the time.[9] The German authorities instead justified prosecution merely on the basis of the German law and the interests of the German state.

The British government could do nothing to help her. Sir Horace Rowland of the Foreign Office said, "I am afraid that it is likely to go hard with Miss Cavell; I am afraid we are powerless."[10] Lord Robert Cecil, Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs, advised that, "Any representation by us, will do her more harm than good."[10] The United States, however, had not yet joined the war and was in a position to apply diplomatic pressure. Hugh S. Gibson, First Secretary of the U.S. legation at Brussels, made clear to the German government that executing Cavell would further harm Germany's already damaged reputation. Later, he wrote:[11]

We reminded [German civil governor Baron von der Lancken] of the burning of Louvain and the sinking of the Lusitania, and told him that this murder would rank with those two affairs and would stir all civilised countries with horror and disgust. Count Harrach broke in at this with the rather irrelevant remark that he would rather see Miss Cavell shot than have harm come to the humblest German soldier, and his only regret was that they had not "three or four old English women to shoot."

Baron von der Lancken is known to have stated that Cavell should be pardoned because of her complete honesty and because she had helped save so many lives, German as well as Allied. However, General von Sauberzweig, the military governor of Brussels, ordered that "in the interests of the State" the implementation of the death penalty against Baucq and Cavell should be immediate,[4] denying higher authorities an opportunity to consider clemency.[5][12] Cavell was defended by lawyer Sadi Kirschen from Brussels. Of the 27 persons put on trial, five were condemned to death: Cavell, Baucq (an architect in his thirties), Louise Thuliez, Séverin and Countess Jeanne de Belleville. Of the five sentenced to death, only Cavell and Baucq were executed; the other three were granted reprieve.[4]

Cavell was arrested not for espionage, as many were led to believe, but for 'treason', despite not being a German national.[3] She may have been recruited by the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), and turned away from her espionage duties in order to help Allied soldiers escape, although this is not widely accepted.[13] Rankin cites the published statement of M. R. D. Foot, historian and Second World War British intelligence officer, as to Cavell having been part of SIS or MI6.[14] The former director-general of MI5, Stella Rimington, announced in 2015 that she had unearthed documents in Belgian military archives that confirmed an intelligence gathering aspect to Cavell's network. The BBC Radio 4 programme that presented Rimington's quote, noted Cavell's use of secret codes and, though amateurish, other network members' successful transmission of intelligence.[15]

When in custody, Cavell was questioned in French, but the session was minuted in German; which gave the interrogator the opportunity to misinterpret her answers. Although she may have been misrepresented, she made no attempt to defend herself. Cavell was provided with a defender approved by the German military governor; a previous defender, who was chosen for Cavell by her assistant, Elizabeth Wilkins,[3] was ultimately rejected by the governor.[12]

The night before her execution, she told the Reverend Stirling Gahan, the Anglican chaplain who had been allowed to see her and to give her Holy Communion, "Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone."[16] These words are inscribed on her statue in St Martin's Place, near Trafalgar Square in London. Her final words to the German Lutheran prison chaplain, Paul Le Seur, were recorded as, "Ask Father Gahan to tell my loved ones later on that my soul, as I believe, is safe, and that I am glad to die for my country."

From his sick bed Brand Whitlock, the U.S. minister to Belgium, wrote a personal note on Cavell's behalf to Moritz von Bissing, the governor general of Belgium. Hugh Gibson; Maitre G. de Leval, the legal adviser to the United States legation; and Rodrigo Saavedra y Vinent, 2nd Marques de Villalobar, the Spanish minister, formed a midnight deputation of appeal for mercy or at least postponement of sentence.[17] Despite these efforts, on 11 October, Baron von der Lancken allowed the execution to proceed.[5] Sixteen men, forming two firing squads, carried out the sentence pronounced on her, and on four Belgian men at the Tir national[3] shooting range in Schaerbeek, at 7:00 am on 12 October 1915. There are conflicting reports of the details of Cavell's execution. However, according to the eyewitness account of the Reverend Le Seur, who attended Cavell in her final hours, eight soldiers fired at Cavell while the other eight executed Baucq.[3] Her execution, certification of death, and burial were all witnessed by the German poet Gottfried Benn in his capacity as a 'Senior Doctor in the Brussels Government since the first days of the (German) occupation'. Benn wrote a detailed account titled 'Wie Miss Cavell erschossen wurde' (1928), which has recently been translated by David Paisey 'How Miss Cavell was shot' in Gottfried Benn, 'Selected poems and prose'. (Gottfried Benn, Selected poems and prose, Fyfield Books, Carcanet, 2013.)

There is also a dispute over the sentencing imposed under the German Military Code. Supposedly, the death penalty relevant to the offence committed by Cavell was not officially declared until a few hours after her death.[1] The British post-war Committee of Enquiry into Breaches of the Laws of War however regarded the verdict as legally correct.[18]

On instructions from the Spanish minister, Belgian women immediately buried her body next to Saint-Gilles Prison.[5] After the War, her body was taken back to Britain for a memorial service at Westminster Abbey and then transferred to Norwich, to be laid to rest at Life's Green on the east side of the cathedral. The King had to grant an exception to an Order in Council of 1854, which prevented any burials in the grounds of the cathedral, to allow the reburial.[19]

First World War propaganda

In the months and years following Cavell's death, countless newspaper articles, pamphlets, images, and books publicised her story. She became an iconic propaganda figure for military recruitment in Britain, and to help increase favourable sentiment towards the Allies in the United States. She was a popular icon because of her sex, her nursing profession, and her apparently heroic approach to death.[1] Her execution was represented as an act of German barbarism and moral depravity.

News reports shortly following Cavell's execution were found to be only true in part.[3] Even the American Journal of Nursing repeated the fictional account of Cavell's execution in which she fainted and fell because of her refusal to wear a blindfold in front of the firing squad.[3] Allegedly, while she lay unconscious, the German commanding officer shot her dead with a revolver.[5] Numerous accounts like these stimulated international outrage and general anti-German sentiments.

Along with the invasion of Belgium, and the sinking of the Lusitania, Cavell's execution was widely publicised in both Britain and North America by Wellington House, the British War Propaganda Bureau.[20]

Because of the British government's decision to publicise Cavell's story as part of its propaganda effort, she became the most prominent British female casualty of First World War.[12] The combination of heroic appeal and a resonant atrocity-story narrative made Cavell's case one of the most effective in British propaganda of the First World War,[20] as well as a factor in enduring post-war anti-German sentiment.

Before the First World War, Cavell was not well known outside nursing circles.[3] This allowed two different depictions of the truth about her in British propaganda, which were a reply to enemy attempts to justify her shooting, including the suggestion that Cavell, during her interrogation, had given information that incriminated others. In November 1915, the British Foreign Office issued a denial that Cavell had implicated anyone else in her testimony.

One image commonly represented was of Cavell as an innocent victim of a ruthless and dishonourable enemy.[12] This view depicted her as having helped Allied soldiers to escape, but innocent of 'espionage', and was most commonly used in various forms of British propaganda, such as postcards and newspaper illustrations during the war.[12] Her story was presented in the British press as a means of fuelling a desire for revenge on the battlefield.[12] These images implied that men must enlist in the armed forces immediately in order to stop forces that could arrange the judicial murder of an innocent British woman.

Another representation of a side of Cavell during the First World War saw her described as a serious, reserved, brave, and patriotic woman who devoted her life to nursing and died to save others. This portrayal has been illustrated in numerous biographical sources, from personal first-hand experiences of the Red Cross nurse. Pastor Le Seur, the German army chaplain, recalled at the time of her execution, "I do not believe that Miss Cavell wanted to be a martyr…but she was ready to die for her country… Miss Cavell was a very brave woman and a faithful Christian".[3] Another account from Anglican chaplain, the Reverend Gahan, remembers Cavell's words, "I have no fear or shrinking; I have seen death so often it is not strange, or fearful to me!"[5] In this interpretation, her stoicism was seen as remarkable for a non-combatant woman, and brought her even greater renown than a man in similar circumstances would have received.[12]

German response

The Imperial German Government thought that it had acted fairly towards Cavell. In a letter, German undersecretary for Foreign Affairs Dr Alfred Zimmermann (not to be confused with Arthur Zimmermann, German Secretary for Foreign Affairs) made a statement to the press on behalf of the German government:

It was a pity that Miss Cavell had to be executed, but it was necessary. She was judged justly...It is undoubtedly a terrible thing that the woman has been executed; but consider what would happen to a State, particularly in war, if it left crimes aimed at the safety of its armies to go unpunished because committed by women.[21]

From the perspective of the German government, had they released Cavell there might have been a surge in the number of women participating in acts against Germany because they knew they would not be severely punished. It was up to the responsible men to follow their legal duty to Germany and ignore the world’s condemnation. Their laws do not make distinctions between sexes, the only exception to this rule being that according to legal customs, women in a "delicate" (probably this means "pregnant") condition could not be executed.[21] However, in January 1916 the Kaiser decreed that regarding women from now on capital punishment should not be carried out without his explicit prior endorsement.[22]

The German government also believed that all of the convicted people were thoroughly aware of the nature of their acts. The court paid particular attention to this point, releasing several accused persons because there was doubt as to whether the accused knew that their actions were punishable.[21] The condemned, in contrast, knew full well what they were doing and the punishment for committing their crimes because "numerous public proclamations had pointed out the fact that aiding enemies’ armies was punishable with death."[21] The Allied response to this was the same as to Bethmann-Hollweg's announcement of the invasion of Belgium, or the notice given in the papers of intent to sink such ships as the RMS Lusitania; to make a public proclamation of a thing does not make it right.

Burial and memorials

Cavell's remains were returned to Britain after the war. As the ship bearing the coffin arrived in Dover, a full peal of Grandsire Triples (5040 Changes, Parker's Twelve-Part) was rung on the bells of the parish church. The peal was notable: "Rung with the bells deeply muffled with the exception of the Tenor which was open at back stroke, in token of respect to Nurse Cavell, whose body arrived at Dover during the ringing and rested in the town till the following morning. The ringers of 1-2-3-4-5-6 are ex-soldiers, F. Elliot having been eight months Prisoner of War in Germany." Deep (or full) muffling is normally only used for the deaths of sovereigns.[23] After an overnight pause in the parish church the body was conveyed to London and a state funeral was held at Westminster Abbey. On 19 May 1919, her body was reburied at the east side of Norwich Cathedral; a graveside service is still held each October.[24] The railway van known as the Cavell Van that conveyed her remains from Dover to London is kept as a memorial on the Kent and East Sussex Railway and is usually open to view at Bodiam railway station.

In the Church of England's calendar of saints, the day appointed for the commemoration of Edith Cavell is 12 October. This is a memorial in her honour rather than formal canonisation, and so not a "saint's feast day" in the traditional sense.

Following Cavell's death, many memorials were created around the world to remember her. A patriotic song, Remember Nurse Cavell (words by Gordon V. Thompson, music by Jules Brazil) appeared with 1915 British copyright. The name Mount Edith Cavell was given in 1916 to a massive peak in Canada's Jasper National Park. A memorial statue was unveiled on 12 October 1918 by Queen Alexandra on the grounds of Norwich Cathedral, during the opening of a home for nurses which also bore her name.[25]

To commemorate her centenary in 2015, work went ahead to restore Cavell's grave in the grounds of Norwich Cathedral after being awarded a £50,000 grant.[26]

During October 2015, a railway carriage (Cavell Van) used to transport Cavell's body back to the United Kingdom was on display outside the Forum, Norwich.[27]

The centenary was marked by two new musical compositions:

- Eventide: In Memoriam Edith Cavell by Patrick Hawes premiered in Norwich Cathedral in July 2014[28] with a premiere due to take place on the exact centenary of Cavell's death on 12 October 2015 in London.

- Cavell Mass by David Mitchell, performed in Holy Trinity Pro-Cathedral, Brussels on 10 October 2015, together with Haydn's Missa in Angustiis.

Cavell is to be featured on a UK commemorative £5 coin, part of a set to be issued in 2015 by the Royal Mint to mark the centenary of the war.[29]

Other honours include:

Memorials

- a memorial plaque at St Leonard's Hospital, Hackney, London, UK

- a dedication on the war memorial on the grounds of Sacred Trinity Church, Salford, Greater Manchester, UK

- a marble and stone memorial, surmounted by a bust of Cavell, in Kings Domain in Melbourne, Australia[30]

- a memorial by Henry Alfred Pegram outside Norwich Cathedral, UK

- a memorial tower added to St. Mary & St. George Anglican Church, in Jasper, Alberta, Canada.[31]

- a memorial in Peterborough Cathedral,[32] England

- a stone memorial in Paris, one of two statues that Adolf Hitler ordered destroyed on his 1940 visit (the other being that of Charles Mangin)[33]

- a stone memorial, including a statue of Cavell by George Frampton unveiled in 1920, adjacent to Trafalgar Square in London[34][35]

- an inscription on a war memorial, naming the 35 people executed by the German army in Tir National in Schaerbeek, Brussels, Belgium

- monument to Edith Cavell and Marie Depage by Paul Du Bois in Brussels

- a bust in the Montjoiepark in Uccle, Belgium, inaugurated on 12 October 2015 by Princess Anne, Princess Royal of Great Britain and Princess Astrid of Belgium

In popular culture

Films, plays and television

- The first film made of the story was the 1916 Australian silent film The Martyrdom of Nurse Cavell soon followed by Nurse Cavell.

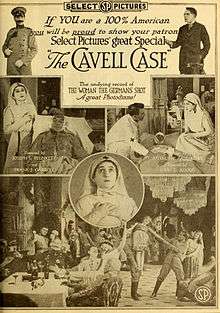

- In 1918 John G. Adolfi directed The Woman the Germans Shot, starring Julia Arthur as Cavell

- Herbert Wilcox made a 1928 silent film based on the story called Dawn with Sybil Thorndike. He remade it as Nurse Edith Cavell (1939) starring Anna Neagle and George Sanders.

- Nurse Cavell, a 1933 play in three acts, by C. S. Forester with C. E. Bechhofer Roberts[36]

- In the second episode of the 1980 television series To Serve Them All My Days, Cavell is mentioned in a speech to the school's Officers' Training Corps.

- In Les plus grands Belges ("The Greatest Belgians"), a 2005 television show on the Belgian French-speaking public channel RTBF, the audience voted Cavell the 48th greatest Belgian.

- In the final episode of the 2014 BBC drama series The Crimson Field, Cavell is mentioned as having been executed, during the interrogation of Sister Joan Livesey.

- "Patriot", a play by Angela Moffat, was premiered at the Grand Theatre Arts Wing, Swansea in October 2014 with Claire Novelli as Edith Cavell.It was produced by Fluellen Theatre Company

Music

- The song "Saint Stephen's End" by The Felice Brothers from their 2008 album The Felice Brothers includes a verse about the death of Cavell.

- The song "Amy Quartermaine" by Manning from the 2011 album Margaret's Children is also based on the life of Cavell.

- The song "Que Sera" on the album Silent June by O'Hooley & Tidow was inspired by the execution of Edith Cavell.[37]

- Eventide: In Memoriam Edith Cavell by Patrick Hawes; a 40-minute oratorio premiered in Norwich Cathedral (where Cavell is buried), July 2014.[38] The London premiere took place in St Clement Danes, The Strand, London, on the exact centenary of her death on 12 October 2015.

- Standing as I do before God by Cecilia McDowall, 2014. An a cappella choral setting of the last reported words of Cavell for soprano solo and five-part choir.

- The Cavell Mass by David Mitchell is a 20-minute-long setting of the Latin Mass, commissioned by the Belgian Edith Cavell Commemoration Group for the centenary of Cavell's execution. Its premiere performance, on 10 October 2015, was in Holy Trinity Pro-Cathedral, Brussels, in the same choir stalls where Cavell sang in 1915.[39]

Other

- A daughter of the great Thoroughbred stallion Man o' War, out of a mare named The Nurse, was named Edith Cavell. Foaled in 1923, Edith Cavell won the 1926 Coaching Club American Oaks and also defeated male horses in other stakes events.

See also

- British nursing matrons from the 19th century

- Other

- Louise de Bettignies, a French spy arrested by the Germans who died in captivity in 1918.

- Mata Hari, a Dutch dancer and courtesan executed by the French in 1917, on charges of spying for Germany.

- Gabrielle Petit, a Belgian nurse executed by the German army for spying for Britain in 1916.

- Andrée de Jongh, a Belgian nurse who, inspired by Cavell, in the Second World War created the Comète Line to repatriate Allied airmen.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Judson 1941.

- 1 2 Unger 1997.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Hoehling 1957.

- 1 2 3 4 Encyclopædia Britannica 1922.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Scovil 1915.

- ↑ The Mount Washington News 1934.

- ↑ Palm Beach Daily News 1936.

- 1 2 3 Duffy 2009.

- ↑ Bevans 1968, p. 972.

- 1 2 Norton-Taylor 2005.

- ↑ Gibson 1917.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hughes 2005.

- ↑ Rankin 2008, p. 36–37.

- ↑ Watson 2014.

- ↑ The Telegraph (online edition) Revealed: New evidence that executed wartime nurse Edith Cavell's network was spying 12 September 2015.

- ↑ Gahan 1925, pp. 288-289.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Americana 1920.

- ↑ First, Second and Third Interim Reports from the Committee of Enquiry into Breaches of the Laws of War, with Appendices; p. 419 ff.; quote (page 424): "From These considerations it follows that the Feldgericht was justified in finding that Miss Cavell had committed the offence with which she was charged, and that it had power under the German law with which it was administering to condemn her to death."

- ↑ London Gazette 1919.

- 1 2 Peterson 1939, p. 61.

- 1 2 3 4 Zimmermann 1916, p. 481.

- ↑ Hull, Isabel V. (2014). A Scrap of Paper: Breaking and Making of International Law during the Great War. Cornell University Press. pp. 108, 109. ISBN 978-0-8014-5273-4.

- ↑ KCACR.

- ↑ Norwich Cathedral.

- ↑ The Times 1918.

- ↑ BBC News 2014b.

- ↑ BBC news report Retrieved 6 October 2015

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-norfolk-28277084

- ↑ BBC News 2014.

- ↑ "Nurse Edith Cavell". Monument Australia. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ↑ Smith 1985, p. 14.

- ↑ Peterborough Cathedral.

- ↑ Goodwin 1994.

- ↑ British Pathe 1920.

- ↑ Reuter's 1920.

- ↑ Roberts and Forester 1933.

- ↑ O'Hooley 2011.

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-norfolk-28277084

- ↑ Mitchell 2015.

References

- "WW1 nurse Edith Cavell to feature on new £5 coin". BBC News. 5 July 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- "Edith Cavell grave in Norwich to be restored". BBC News. 13 October 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- Bevans, Charles Irving (1968). Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776-1949: Multilateral, 1918-1930: 1918-1930. Department of State.

- Nurse Cavell Memorial 1920 (Black and White) (News Reel). London: British Pathe. 1920. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- Duffy, Michael (22 August 2009). "Primary Documents - Maitre G. de Leval on the Execution of Edith Cavell, 12 October 1915". firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

-

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Cavell, Edith". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Cavell, Edith". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York. - Gahan, H. Stirling (Rev'd) (1925). "The Execution of Edith Cavell". America; Great Crises in Our History Told by Its Makers: A Library of Original Sources... Volume XI. Americanization Department, Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States.

- Gibson, Hugh (1917). A Journal from our Legation (the American Legation) in Belgium ... Illustrated from photographs. Hodder & Stoughton.

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns (1994). No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780671642402.

- Hoehling, A A (Oct 1957). "The Story of Edith Cavell". The American Journal of Nursing. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 57 (10): 1320–1322. doi:10.2307/3461516. JSTOR 3461516.

- Hughes, Anne-Marie Claire (2005). "War, Gender and National Mourning: The Significance of the Death and Commemoration of Edith Cavell in Britain". European Review of History: Revue europeenne d'histoire. 12 (3): 425–444. doi:10.1080/13507480500428938.

- Judson, Helen (Jul 1941). "Edith Cavell". The American Journal of Nursing. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 41 (7): 871. doi:10.2307/3415077. JSTOR 3415077.

- KCACR Roll of Honour, Kent County Association of Change Ringers, retrieved 21 October 2014

-

Klein, Henri F. (1920). "Cavell, Edith". In Rines, George Edwin. Encyclopedia Americana.

Klein, Henri F. (1920). "Cavell, Edith". In Rines, George Edwin. Encyclopedia Americana. - The London Gazette: no. 31332. p. 5787. 9 May 1919.

- Mitchell, David (2015). "Cavell Mass". Campbell/Bright Morning Star. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- "Seeks Release as Betrayer of Cavell". The Mount Washington News. 23 February 1934.

- Norton-Taylor, Richard (12 October 2005). "How British diplomats failed Edith Cavell". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- "Nurse Edith Cavell". Norwich Cathedral. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- O'Hooley, Belinda (February 2011). "O'Hooley & Tidow: unconventional and experimental folk". Muso's magazine. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- "Alleged Betrayer Freed". Palm Beach Daily News. 10 March 1936.

- Right dear in the sight of the Lord is the death of His Saints. Peterborough Cathedral. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- Peterson, Horace Cornelius (1939). Propaganda for war: the campaign against American neutrality, 1914-1917.

- Rankin, Nicholas (2008). A Genius for Deception: How Cunning Helped the British Win Two World Wars. Oxford University Press, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-19-976917-9.

- Reuter's (18 March 1920). "Statue of Edith Cavell". Barrier Miner. 33 (9837). Broken Hill, NSW, Australia. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- Roberts, Carl Eric Bechhofer; Forester, Cecil Scott (1933). Nurse Cavell: A Play in Three Acts. John Lane.

- Scovil, Elisabeth Robinson (Nov 1915). "An Heroic Nurse". The American Journal of Nursing. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 16 (2): 118–121. JSTOR 3406248.

- Smith, Cindi (March 1985). A Parish History of the Church of St. Mary and St. George, Jasper, Alberta. Jasper Yellowhead Historical Society.

- "Court Circular". The Times. London. 14 October 1918.

- Unger, Abraham (23 September 1997). "Edith Cavell". HistoryNet. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- Watson, Greig (24 February 2014). "World War One: Edith Cavell and Charles Fryatt 'martyred'". BBC News. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- Zimmermann, Alfred (1916). "A Defense of the Execution". The New York Times Current History. No. 3. New York Times Company.

Further reading

- Alfen, Peter van (2006). "The Meaning of a Memory: The Case of Edith Cavell and the Lusitania in Post-World War I Belgium". American Numismatic Society. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- Arthur, Terri (2011). Fatal Decision: Edith Cavell WWI Nurse. Beagle Books Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-0-9841813-2-2.

- "No reprieve for angel of mercy". BBC News. 9 May 2002. Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- Beck, James Montgomery (1915). The Case of Edith Cavell: a Study of the Rights of Noncombatants ... Reprinted from "New York Times.". New York & London: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- Berkeley, Reginald (1928). Dawn: a biographical novel of Edith Cavell. Sears.

- Boston, Noel (1955). The Dutiful Edith Cavell. Norwich Cathedral.

- Brown, Gordon (2008). "The Heroine who humbled me". Courage: Eight Portraits. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-0-7475-9331-7.

- Cabot, E. Lyman; Fitzgerald, Alice L. F. (2006). The Edith Cavell Nurse from Massachusetts: The War Lettes of Alice Fitzgerald, An, American Nurse Serving in the British Expeditionary Force, Boulogne- The Somme 1916-1917. Meadow Books. ISBN 978-1-84685-202-2.

- Clowes, Peter (12 June 2006). "Edith Cavell: World War I Nurse and Heroine". HistoryNet. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

-

"Cavell, Edith". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

"Cavell, Edith". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921. - "The Death of Edith Cavell". The Daily News & Leader. London: H.C. & L. 1915.* "The Death of Edith Cavell". The Daily News & Leader. London: H.C. & L. 1915.

- Grant, Sally Grant (1995). Edith Cavell, 1865-1915. Larks Press. ISBN 978-0-948400-28-5.

- Grey, Elizabeth (1973). Friend Within the Gates: The Story of Nurse Edith Cavell. Dell Publishing Company.

- Hamelecourt, Juliette Elkon (1956). Edith Cavell, Heroic Nurse. J. Messner.

- Hill, William Thomson (1915). The Martyrdom of Nurse Cavell: The Life Story of the Victim of Germany's Most Barbarous Crime : With Illustrations. London: Hutchinson & Co.

- Hoehling, Adolph A (1957). A whisper of eternity: the mystery of Edith Cavell. T. Yoseloff.

- Johnson, Jan (1 February 1979). The Secret Task of Nurse Cavell: A Story about Edith Cavell. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-03-041661-3.

- Lasswell, Harold Dwight (1927). Propaganda Technique in World War One. MIT Press (MA). ISBN 978-0-262-62018-5.

- Leeuw, Adèle De (1968). Edith Cavell; Nurse, Spy, Heroine. Putnam.

- Marquis, Alice Goldfarb (Jul 1978). "Words as Weapons: Propaganda in Britain and Germany during the First World War". Journal of Contemporary History. Sage Publications, Ltd. 13 (3): 467–498. doi:10.1177/002200947801300304. JSTOR 260205.

- Murphy, William S. (1916). In Memoriam: Edith Cavell. Stoneham.

- Peachment, Brian (1980). Ready to Die: The Story of Edith Cavell. Faith in Action Series. Canterbury Press. ISBN 978-0-08-024189-0.

- Pickles, Katie (2007). Transnational Outrage: The Death and Commemoration of Edith Cavell. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-8607-8.

- Protheroe, Ernest (1916). A Noble Woman ; The Life-story of Edith Cavell. By Ernest Protheroe. Kelly.

- Ryder, Rowland (1975). Edith Cavell. Hamilton.

- Sarolea, Charles (1915). The Murder of Nurse Cavell. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- Souhami, Diana (2010). Edith Cavell. Quercus. ISBN 978-1-84916-359-0.

- Til, Jacqueline van (1922). With Edith Cavell in Belgium. H.W. Bridges. ISBN 978-1-153-21140-6.

- Vinton, Iris (1960). The Story of Edith Cavell ... Illustrated by Gerald McCann. London.

- Ward, Richard Heron (1965). The Secret Trial: An Unhistorical Charade Suggested by the Life and Death of Edith Cavell.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edith Cavell. |