Echinococcus granulosus

| Echinococcus granulosus | |

|---|---|

| |

| E. granulosus scolex | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | Cestoda |

| Order: | Cyclophyllidea |

| Family: | Taeniidae |

| Genus: | Echinococcus |

| Species: | E. granulosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Echinococcus granulosus Batsch, 1786 | |

Echinococcus granulosus, also called the hydatid worm, hyper tape-worm or dog tapeworm, is a cyclophyllid cestode that parasitizes the small intestine of canids as an adult, but which has important intermediate hosts such as livestock and humans, where it causes cystic echinococcosis, also known as hydatid disease. The adult tapeworm ranges in length from 3 mm to 6 mm and has three proglottids ("segments") when intact—an immature proglottid, mature proglottid and a gravid proglottid.[1] The average number of eggs per gravid proglottid is 823. Like all cyclophyllideans, E. granulosus has four suckers on its scolex ("head"), and E. granulosus also has a rostellum with hooks. Several strains of E. granulosus have been identified, and all but two are noted to be infective in humans.[2]

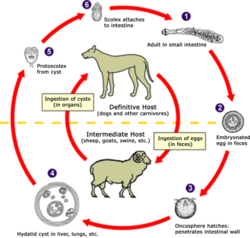

The lifecycle of E. granulosus involves dogs and wild carnivores as a definitive host for the adult tapeworm.[3] Definitive hosts are where parasites reach maturity and reproduce. Wild or domesticated ungulates, such as sheep, serve as an intermediate host.[3] Transitions between life stages occur in intermediate hosts. The larval stage results in the formation of echinococcal cysts in intermediate hosts.[3] Echinococcal cysts are slow growing,[3] but can cause clinical symptoms in humans and be life-threatening.[4] Cysts may not initially cause symptoms, in some cases for many years.[3] Symptoms developed depend on location of the cyst, but most occur in the liver, lungs, or both.[4]

E. granulosus was first documented in Alaska but is distributed world-wide. It is especially prevalent in parts of Eurasia, north and east Africa, Australia, and South America.[4] Communities that practice sheep farming experience the highest risk to humans,[4] but wild animals can also serve as an avenue for transmission. For example, dingoes serve as a definitive host before larvae infect sheep in the mainland of Australia.[4] Sled dogs may expose moose or reindeer to E. granulosus in parts of North America and Eurasia.[4]

Transmission

E. granulosus requires two host types, a definitive host and an intermediate host. The definitive host of this parasite are dogs and the intermediate host are most commonly sheep, however, cattle, horses, pigs, goats, and camels are also potential intermediate hosts.[5] Humans can also be an intermediate host for E. granulosus, however this is uncommon and therefore humans are considered an aberrant intermediate host.[5]

E. granulosus is ingested and attaches to the mucosa of the intestines in the definitive host and there the parasite will grow into the adult stages.[6] Adult E. granulosus release eggs within the intestine which will be transported out of the body via feces.[6] When contaminated waste is excreted into the environment, intermediate host has the potential to contract the parasite by grazing in contaminated pasture, perpetuating the cycle.[5][7]

E. granulosus is transmitted from the intermediate host (sheep) to the definitive host (dogs) by frequent feeding of offal, also referred to as “variety meat” or “organ meat”. Consuming offal containing E. granulosus can lead to infection; however, infection is dependent on many factors.[4]

The frequency of offal feedings, the prevalence of the parasites within the offal, and the age of the intermediate host are factors that affect infection pressure within the definitive host.[6] The immunity of both the definitive and intermediate host plays a large role in the transmission of the parasite, as well as the contact rate between the intermediate and the definitive host (such as herding dogs and pasture animals being kept in close proximity where dogs can contaminate grazing areas with fecal matter).[4]

The life expectancy of the parasite, coupled with the frequency of anthelminthic treatments, will also play a role in the rate of infection within a host. The temperature and humidity of the environment can affect the survival of E. granulosus.[4]

Once sheep are infected, the infection typically remains within the sheep for life. However, in other hosts, such as dogs, treatment for annihilating the parasite is possible. However, the intermediate host is assumed to retain a greater life expectancy than the definitive host.[4][7]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis in the definitive host, the dog, may be done by post mortem examination of the small intestine, or with some difficulty ante mortem by purging with arecoline hydrobromate. Detection of antigens in feces by ELISA is currently the best available technique.[8] The prevalence of Echinococcus granulosus was found to be 4.35% in a 2008 study in Bangalore, India [9] employing this coproantigen detection technique. Polymerase Chain Reaction(PCR) is also used to identify the parasite from DNA isolated from eggs or feces.[8]

Risk in humans

Humans should avoid handling stool of dogs and avoid eating infected animals and home slaughtering animals. If a human becomes infected there are a variety of methods for treatment.[2][10] The most common treatment in the past years has been surgical removal of the hydatid cysts.[10] Cyst manipulation should be performed with caution, as spilling of cyst contents can cause anaphylactic shock. However, in recent years, less invasive treatments have been developed such as cyst puncture, aspiration of the liquids, the injection of chemicals, and then re-aspiration.[2] Benzimidazole-based chemotherapy is also a new treatment option for humans.[2]

Prevention

.tif.jpg)

In order to prevent transmission to dogs from intermediate hosts, dogs can be given anthelminthic vaccinations.[3][10] In the case of intermediate hosts, especially sheep, these anthelminthic vaccinations do cause an antigenic response—meaning the body produces antibodi avinash response—however it does not prevent infection in the host.[3][10] Clean slaughter and high surveillance of potential intermediate host during slaughter is key in preventing the spread this cestode to its definitive host. It is vital to keep dogs and potential intermediate host as separated as possible to avoid perpetuating infection.[3][11] According to mathematical modeling, vaccination of intermediate hosts, coupled with dosing definitive hosts with anthelminths is the most effect method for intervening with infection rates.[3]

Proper disposal of carcasses and offal after home slaughter is difficult in poor and remote communities and therefore dogs readily have access to offal from livestock, thus completing the parasite cycle of Echinococcus granulosus and putting communities at risk of cystic echinococcosis. Boiling livers and lungs which contain hydatid cysts for 30 minutes has been proposed as a simple, efficient and energy- and time-saving way to kill the infectious larvae.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ Pedro-Pons, Agustín (1968). Patología y Clínica Médicas (in Spanish). 6 (3rd ed.). Barcelona: Salvat. p. 955. ISBN 84-345-1106-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Eckert J, Deplazes P (January 2004). "Biological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17 (1): 107–35. doi:10.1128/cmr.17.1.107-135.2004. PMC 321468

. PMID 14726458.

. PMID 14726458. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Moro P, Schantz PM (March 2009). "Echinococcosis: a review". Int. J. Infect. Dis. 13 (2): 125–33. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2008.03.037. PMID 18938096.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 McManus DP, Zhang W, Li J, Bartley PB (October 2003). "Echinococcosis". Lancet. 362 (9392): 1295–304. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14573-4. PMID 14575976.

- 1 2 3 Torgerson PR, Heath DD (2003). "Transmission dynamics and control options for Echinococcus granulosus". Parasitology. 127 (7): S143–58. doi:10.1017/s0031182003003810. PMID 15027611.

- 1 2 3 Moro PL, McDonald J, Gilman RH, et al. (1997). "Epidemiology of Echinococcus granulosus infection in the central Peruvian Andes". Bull. World Health Organ. 75 (6): 553–61. PMC 2487032

. PMID 9509628.

. PMID 9509628. - 1 2 Lahmar S, Debbek H, Zhang LH, et al. (May 2004). "Transmission dynamics of the Echinococcus granulosus sheep-dog strain (G1 genotype) in camels in Tunisia". Vet. Parasitol. 121 (1-2): 151–6. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.02.016. PMID 15110412.

- 1 2 Varcasia, A.; Garippa, G.; Scala, A. (2004). "Diagnosis of Echinococcus granulosus in dogs". Parassitologia. 46 (4): 409–412. PMID 16044702.

- ↑ Prathiush, P. R.; D'Souza, P. E.; Gowda, A. K. J. (2008). "Diagnosis of Echinococcus granulosus infection in dogs by a coproantigen sandwich ELISA". Veterinarski Arhiv. 78 (4): 297–305.

- 1 2 3 4 Craig PS, McManus DP, Lightowlers MW, et al. (June 2007). "Prevention and control of cystic echinococcosis". Lancet Infect Dis. 7 (6): 385–94. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70134-2. PMID 17521591.

- 1 2 3 Li, Jun; Wu, Chuanchuan; Wang, Hui; Liu, Huanyuan; Vuitton, Dominique A.; Wen, Hao; Zhang, Wenbao (2014). "Boiling sheep liver or lung for 30 minutes is necessary and sufficient to kill Echinococcus granulosus protoscoleces in hydatid cysts". Parasite. 21: 64. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014064. ISSN 1776-1042.

External links

- Echinococcus granulosus

- "Echinococcus granulosus". NCBI Taxonomy Browser. 6210.