Dog Tax War

The Dog Tax war is described by some authors as the last gasp of the 19th-century wars between the Māori and the Pākehā, the British settlers of New Zealand. It was, however, a bloodless "war", with only a few shots being fired.

The tax

In the 1890s the Hokianga County Council imposed a tax of 2/6d (half crown) on each dog in the district. Many people, particularly in the South Hokianga, refused to pay, one of which was Hone Riiwi Toia. It was this encroachment of British colonial laws over Māori autonomy that instigated an armed protest, the response to which became known as the Dog Tax War.

The role of religion

Hone Toia was the leader/prophet of a breakaway group of Wesleyans called Te Huihuinga or Te Huihui.[1] Te Huihuinga was also a political movement and considered themselves as having seceded to 'Te Kotahitanga' (an autonomous Māori parliament movement founded upon 'Te Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tïreni' 1835 (Declaration of Independence)). Other grievances held by this group included seasonal restrictions on the hunting of native birds, the land tax (on land held under Crown grant within five miles of a public road), the wheel tax (on vehicles with certain tyre widths).

It was during a Te Huihui meeting that Hone Toia prophesied that "if dogs were to be taxed, men would be next".

Hone had met with Te Whiti-o-Rongomai the leader of the Pai Marire (good and peaceful) movement, Te Huihuinga adopted aspects of this movement which sought to retain their right to live as Māori without interference, and to make use of their traditional resources as guaranteed by the Treaty of Waitangi.

Europeans regarded Hone Toia as an imposter, other associated him with the Hau Hau movement. This was a vehemently anti-Pākehā cult that had developed in the 1860s and spread throughout the North Island, and had been heavily involved in the later major conflicts, the Second Taranaki War and others subsequently.

Enforcement

In June 1897, Henry Menzies was put in charge of dog registrations by the Hokianga County Council, for which he received only the commission of one shilling for each dog collar sold. In 1898 he served 40 summons at Pukemiro pa (Hone Toia's village in Hauturu), where Menzies was rumoured to have said, that if the people refused to pay they would be sent to an ice-bound country where their bones would crack from the cold, (probably referring to the prisons of the lower south island).

This suitably terrified the people of Te Huihuinga, some choosing to sleep in the bush out of fear of being arrested. Hone Toia intervened successfully achieving an adjournment to the summons, he then set up a meeting at Pukemiro on 28 April, inviting Seon, Constable Alexander McGilp, Menzies and others.

Resistance begins

Returning to the Hokianga, on 28 April 1898, Seon, Constable Alexander McGilp, Menzies and others attended the meeting. There they found one hundred and fifty men led by Hone Toia. Romana te Paehangi an elder and relative of Hone stated that they would not pay any taxes and that 'they would die on account of these taxes'. Hone Toia confirmed that they would rather resist than be driven further into poverty and hardship.

At Pukemiro they also announced their intention to come to Rawene (the administrative centre of the area) with their guns to continue their dispute with the County Council. They also gave assurances that no women or children or settlers would be hurt and that there would be no bloodshed unless they came in contact with the law. A telegraph was composed at the meeting and sent to Clendon in Hone Toia's name, however the message received was understood to mean that war would be waged because of the dog tax and that blood would be shed.

In Rawene panic ensued, many people withdrew to neighbouring Kohukohu or aboard the steamer 'Glenburg'.

A police inspector and five constables arrived by boat from Auckland and set up a cannon on the wharf. The party of less than 20 including Hone Toia and led by Romana Te Paehangi duly appeared, stripped for war, ready to present themselves to the law. The outnumbered police sensibly fled leaving their cannon behind. Rawene was deserted apart from a few neutral Māori and a handful of Pākehā including Rev. Gittos, and contractor Robert Cochrane. Cochrane described the war party as quiet, expressing friendship to all but the law and as stating that they would not fire first. Gittos and Cochrane eventually persuaded them to return to Waima later that evening.

Descendants of the men involved described how Bob Cochrane ran the local hotel. Despite it being a Sunday and therefore illegal, he agreed to open the bar and served the visiting war party with beer. This gesture of goodwill went a long way to defusing the situation.

Some four days later the government had assembled a force of 120 men armed with rifles, two field guns and two rapid fire guns landed in Rawene. The force under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Stuart Newall and was later reinforced by the British warship Torch.

On 5 May 1898, the government forces marched on Waima, Hone Toia sent a message requesting Newall wait at Omanaia, Newall refused. An ambush was feared at the crest of the hill between Waima and Rawene, after two shots were fired over the heads of the colonial troops. However the soldiers were allowed to pass unmolested and carried on to set up camp at Waima School. Toia and his men being camped some distance away.

Surrender and imprisonment of Hone Toia

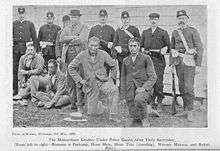

The potential was there for serious conflict. However the situation was defused by the timely arrival of the Member of the House of Representative (MHR) for Northern Māori, Hone Heke Ngapua. He was the grand-nephew of the famous Hone Heke. He met with Hone Toia and negotiated a truce and the surrender of Hone, his people and some of their guns. Hone Toia was arrested on 6 May with four others,[2] 11 more were arrested later.

Hone Heke Ngapua had previously sent a telegraph to Hone Toia, advising him to disband his people, withdraw peacefully and to petition parliament, this was seen as a wise move by Heke, considering such acts as the 1863 Suppression of Rebellion Act, which suspended habeas corpus and introduced martial law into disturbed districts, and the New Zealand Settlements Act, which provided for the punitive confiscation of 'rebel natives' land.

Charged with "Intending by conspiring to levy war against the Queen in order to force her to change her measures, and conspiring by force to prevent collection of taxes", Hone and four others were sentenced for a total of two and a half years of hard labour. Others were subsequently fined and heavy costs imposed, but these were later remitted.

Hone Toia near the end of his sentence in Mount Eden prison, prophesied the date of the Huihuinga prisoners release, as the predicted day wore on his powers appeared to have left him, but later that night at 9pm, it was announced and the prisoners released. Te Huihuinga were released short of their full sentence, on 15 March 1899, this was probably due to the petitions of numerous Iwi (tribes) of the Hokianga and far north.

These events are still remembered to this day; the dog tax in the Hokianga remains, yet is still somewhat neglected, up to this very day.

References

- ↑ Angela Ballara. 'Toia, Hone Riiwi - Biography', from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 1-Sep-10

- ↑ "TROUBLE SATISFACTORILY SETTLED.". Marlborough Express. 7 May 1898. p. 2.

Further reading

- Lee, Jack (1987). Hokianga. Hodder and Stoughton.

- Biography of Hone Toia, a leading figure of the war