Direction vector

In mathematics, a direction vector that describes a line D is any vector

where and are two distinct points on the line. If v is a direction vector for D, so is kv for any nonzero scalar k; and these are in fact all of the direction vectors for the line D. Under some definitions, the direction vector is required to be a unit vector, in which case each line has exactly two direction vectors, which are negatives of each other (equal in magnitude, opposite in direction).

Parametric equation for a line

In Euclidean space (any number of dimensions), given a point a and a nonzero vector v, a line is defined parametrically by (a+tv), where the parameter t varies between -∞ and +∞. This line has v as a direction vector.

Generative versus predicate forms

The line equation a+tv is a generative form, but not a predicate form. Points may be generated along the line given values for a, t and v:

p ← a +tv

However, in order to function as a predicate, the representation must be sufficient to easily determine ( T / F ) whether any specified point p is on the given line [ a, v ]. If you substitute a known point into the above equation, it cannot be evaluated for equality because t was not supplied, only [ a, v ] and p.

Predicate form of 2D line equation

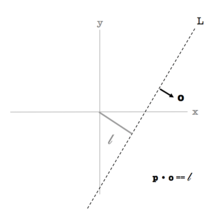

An example of a predicate form of the vector line equation in 2D is:

p • o == L

Here, the line is represented by two features: o and L, shown graphically in the illustration.

o is the line's orientation, a normalized direction vector (unit vector) pointing perpendicular to its run direction (see illustration).

The orientation is computed using the same two quantities dx and dy that go into computing slope m:

o ← ( dy, -dx ) norm = ( dy, -dx ) / || ( dy, -dx ) || (orientation of a 2D line)

Orientation o has the advantage of not overcompressing the information vested in dx and dy into a single scalar as slope does, avoiding the need to appeal to infinity as a value. Numerical algorithms benefit by avoiding such ill-behaved exceptions (e.g. , slope of a vertical line).

The 2nd feature of a 2D line represented this way is its location L. Intuitively and visually, L is the signed distance of the line from the origin (with positive distance increasing along direction o). Orientation must be solved before determining location. Once o is known, L can be computed given any known point p on the line:

L ← p • o (location of a 2D line)

Lines may be represented as feature pair ( o , L ) in all cases. Every line has an equivalent representation ( -o , -L ).

To determine if a point p is on the line, plug the value of p into the vector line predicate and evaluate it:

p • o == L (vector line predicate)

In computation, the predicate must tolerate finite math error by incorporating an epsilon signifying acceptable equality:

abs (p • o - L) < epsilon (finite precision vector line predicate)

The predicate form for 2D lines can be extended to higher dimensions, using coordinate rotation (by matrix rotation). The general form is:

R p == L

where R is the matrix rotation that aligns the line with an axis, and L is the invariant vector Location of points on the line under this rotation.

See also

External links

- Glossary, Nipissing University

- Finding the vector equation of a line

- Lines in a plane - Orthogonality, Distances, MATH-tutorial

- Coordinate Systems, Points, Lines and Planes

- Bierre, Pierre (2010). Flexing the Power of Algorithmic Geometry (1st ed.). Spatial Thoughtware. ISBN 978-0-9827526-0-9.