Pedanius Dioscorides

| Pedanius Dioscorides | |

|---|---|

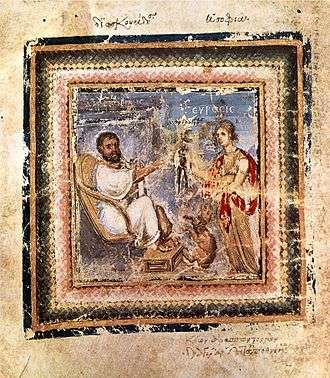

Dioscorides as depicted in a 1240 Arabic edition of De Materia Medica | |

| Born |

c. 40 AD Anazarbus, Cilicia, Asia Minor |

| Died | c. 90 AD |

| Other names | Dioscurides |

| Occupation | Army physician, pharmacologist, botanist |

| Known for | De Materia Medica |

Pedanius Dioscorides (Ancient Greek: Πεδάνιος Διοσκουρίδης, Pedianos Dioskorides; c. 40 – 90 AD) was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of De Materia Medica (Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς) —a 5-volume Greek encyclopedia about herbal medicine and related medicinal substances (a pharmacopeia), that was widely read for more than 1,500 years. He was employed as a medic in the Roman army.

Life

A native of Anazarbus, Cilicia, Asia Minor, Dioscorides practised medicine in Rome during the reign of the emperor Nero. He was a surgeon with the Roman army, which gave him the opportunity to travel extensively, at the same time seeking medicinal substances (plants and minerals) from all over the Roman Empire. The name Pedanius is Roman, suggesting that an aristocrat of that name sponsored him to become a Roman citizen. He dedicated his medical books to Laecanius Arius, a medical practitioner of Tarsus in Cilicia, so he may have studied medicine there.[lower-alpha 1][2][3]

De Materia Medica

Between AD 50 and 70 [4] Dioscorides wrote a five-volume book in his native Greek, Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς, known more widely by its Latin title De Materia Medica ("On Medical Material") which became the precursor to all modern pharmacopeias.[5]

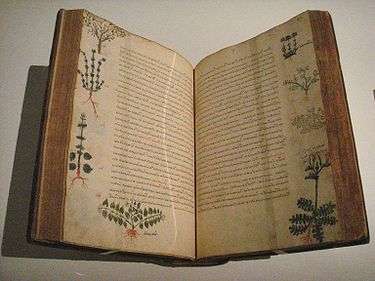

In contrast to many classical authors, Dioscorides' works were not "rediscovered" in the Renaissance, because his book had never left circulation; indeed, with regard to Western materia medica through the early modern period, Dioscorides' text eclipsed the Hippocratic corpus.[6] In the medieval period, De Materia Medica was circulated in Greek, as well as Latin and Arabic translation.[7] While being reproduced in manuscript form through the centuries, it was often supplemented with commentary and minor additions from Arabic and Indian sources. A number of illustrated manuscripts of De Materia Medica survive. The most famous of these is the lavishly illustrated Vienna Dioscurides, produced in Constantinople in 512/513 AD. Densely illustrated Arabic copies survive from the 12th and 13th centuries, while Greek manuscripts survive today in the monasteries of Mount Athos.[8]

De Materia Medica is the prime historical source of information about the medicines used by the Greeks, Romans, and other cultures of antiquity. The work also records the Dacian[9] and Thracian[10] names for some plants, which otherwise would have been lost. The work presents about 600 plants in all,[11] although the descriptions are sometimes obscurely phrased, leading to comments such as: "Numerous individuals from the Middle Ages on have struggled with the identity of the recondite kinds",[12] while some of the botanical identifications of Dioscorides' plants remain merely guesses.

De Materia Medica formed the core of the European pharmacopeia through the 19th century, suggesting that "the timelessness of Dioscorides' work resulted from an empirical tradition based on trial and error; that it worked for generation after generation despite social and cultural changes and changes in medical theory".[6]

The Dioscorea genus of plants, which includes the yam, was named after him by Linnaeus.

Images

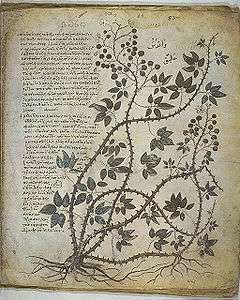

Dioscorides receives a mandrake root, an illumination from the Vienna Dioscurides

Dioscorides receives a mandrake root, an illumination from the Vienna Dioscurides

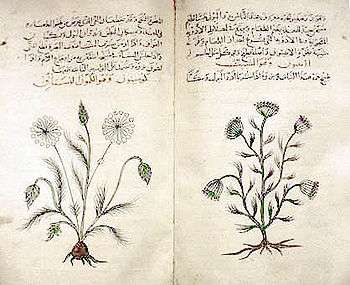

Cumin and dill from an Arabic book of simples (ca. 1334) after Dioscorides (British Museum)

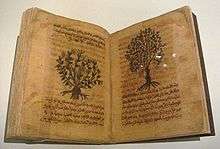

Cumin and dill from an Arabic book of simples (ca. 1334) after Dioscorides (British Museum) Byzantine De Materia Medica, 15th century

Byzantine De Materia Medica, 15th century Later representation of Dioscorides

Later representation of Dioscorides

Translations

- De Materia Medica: Being an Herbal with many other medicinal materials, Englished by Tess Anne Osbaldeston, year 2000, based on the translation of John Goodyer of year 1655 (see below). (Publisher Ibidis Press: Johannesburg).

- De Materia Medica, translated by Lily Y. Beck (2005). (Publisher Hildesheim: Olms-Weidmann).

- The Greek Herbal of Dioscorides... Englished by John Goodyer A. D. 1655, edited by R.T. Gunter (1933).

- De Materia medica : libri V Eiusdem de Venenis Libri duo. Interprete Iano Antonio Saraceno Lugdunaeo, Medico, translated by Janus Antonius Saracenus (1598).

In Literature

In Voltaire's Candide, the title character's injuries received at the hands of the Bulgarian army, into which he had been conscripted, are healed using "emollients taught by Dioscorides."

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Scarborough and Nutton, 1982

- 1 2 Stobart, Anne (2014). Critical Approaches to the History of Western Herbal Medicine: From Classical Antiquity to the Early Modern Period. A&C Black. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-4411-8418-4.

- ↑ Borzelleca, Joseph F.; Lane, Richard W. (2008). "The Art, the Science, and the Seduction of Toxicology: an Evolutionary Development". In Hayes, Andrew Wallace. Principles and methods of toxicology (5th ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 13.

- ↑ "Greek Medicine". National Institutes of Health, USA. 16 September 2002. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ↑ Forbes, 2013

- 1 2 De Vos (2010) "European Materia Medica in Historical Texts: Longevity of a Tradition and Implications for Future Use", Journal of Ethnopharmacology 132(1):28–47

- ↑ Some detail about medieval manuscripts of De Materia Medica at pages xxix–xxxi in Introduction to Dioscorides Materia Medica by TA Osbaldeston, year 2000.

- ↑ Selin, Helaine (2008). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer. p. 1077.

- ↑ Nutton, Vivian (2004). Ancient Medicine. Routledge.. Page 177.

- ↑ Murray, J. (1884). The Academy. Alexander and Shephrard.. Page 68.

- ↑ Krebs, Robert E.; Krebs, Carolyn A. (2003). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Ancient World. Greenwood Publishing Group.. Pages 75–76.

- ↑ Isely, Duane (1994). One hundred and one botanists. Iowa State University Press.

Sources

- Allbutt, T. Clifford (1921). Greek medicine in Rome. London: Macmillan. ISBN 1-57898-631-1.

- Bruins: Codex Constantinopolitanus: Palatii Veteris NO. 1 [3 volume set] Part 1: Reproduction of the Manuscript; Part 2: Greek Text; Part 3: Translation and Commentary Bruins, E. M. (Ed.)

- Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, Daniel; Henley, David (2013). 'Pedanius Dioscorides' in: Health and Well Being: A Medieval Guide. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books.

- Hamilton, J. S. (1986). "Scribonius Largus on the medical profession". Bulletin of the history of medicine. 60 (2): 209–216. PMID 3521772.

- Lazris, J.; Stavros, V. (2013). "L'image paradigmatique: des Schémas anatomiques d'Aristote au De materia medica de Dioscoride". Pallas. 93: 131–164.

- Lazris, J.; Stavros, V. "The medical illustration in Antiquity". Reality Through Image: 18–23 (abstract).

- Riddle, John (1980). "Dioscorides" (PDF). Catalogus Translationum et Commentariorum. 4: 1. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- Riddle, John M. (1985). Dioscorides on pharmacy and medicine. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-71544-7.

- Sadek, M. M. (1983). The Arabic materia medica of Dioscorides. Québec, Canada: Les Éditions du sphinx. ISBN 2-920123-02-5.

- Scarborough, J.; Nutton, V. (1982). "The Preface of Dioscorides' Materia Medica: introduction, translation, and commentary". Transactions & studies of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. 4 (3): 187–227. PMID 6753260.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pedanius Dioscorides. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Pedanius Dioscorides |

- Works by Dr. Dioscorides at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Pedanius Dioscorides at Internet Archive

- Works by Dioscorides

- Dioscorides Material Medica, in English—the full book downloadable in PDF fileformat.

- "Dioscurides Neapolitanus: Codex ex Vindobonensis Graecus 1" (in Italian and Latin). Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- "Medic: Catalogue des textes en ligne: Dioscoride/Dioscodirides, Pedanius" (pdf) (in French and Latin). Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de médecine et d'odontologie, Université Paris Descartes. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- Pedacio Dioscorides anazarbeo: Acerca de la materia medicinal y de los venenos mortiferos, Antwerp, 1555, digitized at Biblioteca Digital Hispánica, Biblioteca Nacional de España

- Les VI livres de Ped. Diosc. de la materie medicinale, Lyon (1559), French edition