United States involvement in regime change

United States involvement in regime change has entailed both overt and covert actions aimed at altering, replacing, or preserving foreign governments. In the latter half of the 19th century, the U.S. government undertook regime change actions mainly in Latin America and the southwest Pacific, and included the Mexican-American, Spanish-American and Philippine-American wars. At the onset of the 20th century the United States shaped or installed friendly governments in many countries including Panama, Honduras, Nicaragua, Mexico, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic.

In the aftermath of World War II, the U.S. government expanded the geographic scope of its regime change actions, as the country struggled with the Soviet Union for global leadership and influence within the context of the Cold War. Significant involvements included the 1950 Korean War, the 1953 Iranian coup d'état, the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion targeting Cuba, the Vietnam War, and support for the Argentinian Dirty War, but included other operations throughout the world.

Also after World War II, the United States in 1945 ratified[1] the UN Charter, the preeminent international law document,[2] which legally bound the U.S. government to the Charter's provisions, including Article 2(4), which prohibits the threat or use of force in international relations, except in very limited circumstances.[3] Therefore, any legal claim advanced to justify regime change by a foreign power carries a particularly heavy burden.[4]

Following the Dissolution of the Soviet Union, the United States has led or supported wars to determine the governance of a number of countries. Stated U.S. aims in these conflicts have included fighting the War on Terror as in the 2001 Afghan war, or removing dictatorial and hostile regimes in the 2003 Iraq War and 2011 military intervention in Libya.

19th century interventions

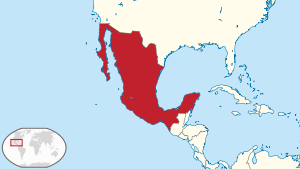

- 1846 U.S.–Mexico War. The Mexican–American War was an armed conflict between the United States of America and Mexico from 1846 to 1848 in the wake of the 1845 U.S. annexation of Texas, which Mexico considered part of its territory despite the 1836 Texas Revolution.

- American forces occupied New Mexico and California, then invaded parts of Northeastern Mexico and Northwestern Mexico; Another American army captured Mexico City, and the war ended in victory of the U.S.

- The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo specified the major consequence of the war: the forced Mexican Cession of the territories of Alta California and New Mexico to the U.S. in exchange for $18 million. In addition, the United States forgave debt owed by the Mexican government to U.S. citizens. Mexico accepted the loss of Texas and thereafter cited the Rio Grande as its national border.

.svg.png)

- 1887 Samoa. The Samoan crisis was a confrontation between the United States, Germany and Great Britain from 1887–1889 over control of the Samoan Islands during the Samoan Civil War.[5] The Samoan Civil War continued, involving Germany and the Americans, eventually resulting, via the Tripartite Convention of 1899, in the partition of the Samoan Islands into American Samoa and German Samoa.[6][7]

.svg.png)

- 1893 Hawaii. The overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii refers to an event of January 17, 1893, in which anti-monarchial elements within the Kingdom of Hawaii, composed largely of American citizens, engineered the overthrow of its native monarch, Queen Lili'uokalani. Hawaii was initially reconstituted as an independent republic, but the ultimate goal of the revolutionaries was the annexation of the islands to the United States, which was finally accomplished in 1898.

1895–1917

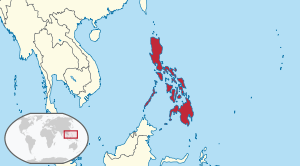

- 1898 Cuba and Puerto Rico, as part of the Spanish–American War, U.S. invaded and occupied Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines in 1898. Cuba was occupied by the U.S. from 1898–1902 under military governor Leonard Wood, and again from 1906–1909, 1912 and 1917–1922; governed by the terms of the Platt Amendment through 1934.

- The Puerto Rican Campaign was an American military sea and land operation on the island of Puerto Rico during the Spanish–American War. The United States Navy attacked the archipelago's capital, San Juan. Though the damage inflicted on the city was minimal, the Americans were able to establish a blockade in the city's harbor, San Juan Bay. The land offensive began on July 25 with 1,300 infantry soldiers.

- All military actions in Puerto Rico were suspended on August 13, after U.S. President William McKinley and French Ambassador Jules Cambon, acting on behalf of the Spanish government, signed an armistice whereby Spain relinquished its sovereignty over the territories of Puerto Rico, Cuba, the Philippines and Guam.

- 1899 Philippines, the Philippine–American War was part of a series of conflicts in the Philippine struggle for independence against United States occupation. Fighting erupted between U.S. and Filipino revolutionary forces on February 4, 1899, and quickly escalated into the 1899 Battle of Manila. On June 2, 1899, the First Philippine Republic officially declared war against the United States.[8] The war officially ended on July 4, 1902.[9]

_(-mini_map_-rivers).svg.png)

- 1900 China. The Boxer Rebellion was a proto-nationalist movement in China between 1898 and 1901. The US was part of an Eight-Nation Alliance that brought 20,000 armed troops to China, defeated the Imperial Chinese Army, and captured Beijing. The Boxer Protocol of 7 September 1901 ended the uprising.[10]

- 1903 Panama. In 1903, Panama seceded from the Republic of Colombia, backed by the U.S. government,[11] amidst the Thousand Days' War. The Panama Canal was under construction by then, and the Panama Canal Zone, under United States sovereignty, was then created. The zone was transferred to Panama in 2000.

- 1903 Honduras, where the United Fruit Company and Standard Fruit Company dominated the country's key banana export sector and associated land holdings and railways, saw insertion of American troops in 1903, 1907, 1911, 1912, 1919, 1924 and 1925.[12] Writer O. Henry coined the term "Banana republic" in 1904 to describe Honduras.

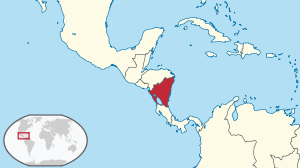

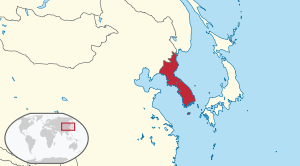

- 1912 Nicaragua, which, after intermittent landings and naval bombardments in the previous decades, was occupied by the U.S. almost continuously from 1912 through 1933.

- 1914 Mexico, US troops occupied Veracruz. See also United States involvement in the Mexican Revolution.

- 1915 Haiti. Haiti was occupied by the U.S. from 1915–1934, which led to the creation of a new Haitian constitution in 1917 that instituted changes that included an end to the prior ban on land ownership by non-Haitians. Including the First and Second Caco Wars.[13]

- 1916 Dominican Republic, actions in 1903, 1904, and 1914; occupied by the U.S. from 1916–1924.

WWI and interwar period

- 1918 Russia. The Allies intervened in the Russian Civil War. About 250,000 foreign troops entered Russia during the Russian civil war fought by the White Army against the new Soviet government. Western and imperial Japan government forces included 13,000 American troops invading through Arkhangelsk and Vladivostok, whose mission after the end of World War I was to topple the Soviet government.

- 1941 Panama The United States government used its contacts in the Panama National Guard, which the U.S. had earlier trained, to have the government of Panama overthrown in a bloodless coup. The U.S. had requested that the government of Panama allow it to build over 130 new military installations inside and outside of the Panama Canal Zone, and the government of Panama refused this request at the price suggested by the U.S.[14]

Post-World War II

- 1953 Iranian coup d'état (known in Iran as the 28 Mordad coup[15]) was the overthrow of the democratically elected government of Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh on 19 August 1953, orchestrated by the intelligence agencies of the United Kingdom (under the name 'Operation Boot') and the United States (under the name TPAJAX Project).[16][17][18] The coup saw the transition of Mohammad-Rezā Shāh Pahlavi from a constitutional monarch to an authoritarian one who relied heavily on United States government support to hold on to power until his own overthrow in February 1979.[19]

.svg.png)

- 1954 Guatemala In a CIA operation code named Operation PBSUCCESS, the U.S. government executed a coup d'état that was successful in overthrowing the democratically-elected government of President Jacobo Árbenz and installed the first of a line of brutal right-wing dictators in its place.[20] [21] The perceived success of the operation made it a model for future CIA operations because the CIA lied to the president of the United States when briefing him regarding the number of casualties.[22]

- 1958 Lebanon crisis. The President of the United States, Eisenhower authorized Operation Blue Bat on July 15, 1958. This was the first application of the Eisenhower Doctrine under which the U.S. announced that it would intervene to protect regimes it considered threatened by international communism. The goal of the operation was to bolster the pro-Western Lebanese government of President Camille Chamoun against internal opposition and threats from Syria and Egypt.

- 1961 Cuba Bay of Pigs Invasion The CIA orchestrated a force composed of CIA-trained Cuban exiles to invade Cuba with support and encouragement from the US government, in an attempt to overthrow the Cuban government of Fidel Castro. The invasion was launched in April 1961, three months after John F. Kennedy assumed the presidency in the United States. The Cuban armed forces, trained and equipped by Eastern Bloc nations, defeated the invading combatants within three days.

- 1960s. Operation MONGOOSE was a US government effort to overthrow the government of Cuba.[23] The operation included economic warfare, including an embargo against Cuba, “to induce failure of the Communist regime to supply Cuba's economic needs,” a diplomatic initiative to isolate Cuba, and psychological operations “to turn the peoples' resentment increasingly against the regime.”[24] The economic warfare prong of the operation also included the infiltration by the CIA of operatives to carry out many acts of sabotage against civilian targets, such as a railway bridge, a molasses storage facilities, an electric power plant, and the sugar harvest, notwithstanding Cuba’s repeated requests to the United States government to cease its terrorist operations.[25][26] In addition, the CIA orchestrated a number of assassination attempts against Fidel Castro, head of government of Cuba, including attempts that entailed CIA collaboration with the American mafia.[27][28][29]

- 1965 Dominican Republic. U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson, convinced of the defeat of the Loyalist forces and fearing the creation of "a second Cuba"[30] on America's doorstep, ordered U.S. forces to restore order. The decision to intervene militarily in the Dominican Republic was Lyndon Johnson's personal decision. All civilian advisers had recommended against immediate intervention hoping that the Loyalist side could bring an end to the civil war.

- President Johnson took the advice of his Ambassador in Santo Domingo, W. Tapley Bennett, who suggested that the US interpose its forces between the rebels and those of the junta, thereby effecting a cease-fire. Chief of Staff General Wheeler told a subordinate: "Your unannounced mission is to prevent the Dominican Republic from going Communist."[31] A fleet of 41 vessels was sent to blockade the island, and an invasion was launched. Ultimately, 42,000 soldiers and marines were ordered to the Dominican Republic.

- 1973 Chilean coup d'état was the overthrow of democratically elected President Salvador Allende by the Chilean armed forces and national police. This followed an extended period of social and political unrest between the right dominated Congress of Chile and Allende, as well as economic warfare ordered by US President Richard Nixon.[32] The regime of Augusto Pinochet that followed is notable for having, by conservative estimates, disappeared some 3200 political dissidents, imprisoned 30,000 (many of whom were tortured), and forced some 200,000 Chileans into exile.[33][34][35] The CIA, through Project FUBELT (also known as Track II), worked to secretly engineer the conditions for the coup. The US initially denied any involvement, and though many relevant documents have been declassified in the decades since, a US president has yet to issue any apology for the incident.[36]

.svg.png)

- 1979-1989 Afghanistan. In what was known as "Operation Cyclone," the U.S. government secretly provided weapons and funding for the Mujahadin Islamic guerillas of Afghanistan fighting to overthrow the Afghan government and the Soviet military forces that supported it. Supplies were channeled through the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) of Pakistan.[37][38][39] Although Operation Cyclone officially ended in 1989 with the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan, U.S. government funding for the Mujahadin continued through 1992.[40]

- Destabilizing Nicaragua 1982-1989. The U.S. government attempted to topple the government of Nicaragua by secretly arming, training and funding the Contras, a terrorist group based in Honduras that was created to sabotage Nicaragua and to destabilize the Nicaraguan government.[41][42][43][44] As part of the training, the CIA distributed a detailed "terror manual" entitled "Psychological Operations in Guerrilla War," which instructed the Contras, among other things, on how to blow up public buildings, to assassinate judges, to create martyrs, and to blackmail ordinary citizens.[45] In addition to orchestrating the Contras, the U.S. government also blew up bridges and mined Corinto harbor, causing the sinking of several civilian Nicaraguan and foreign ships and many civilian deaths.[46][47][48][49] After the Boland Amendment made it illegal for the U.S. government to provide funding for Contra activities, the administration of President Reagan secretly sold arms to the Iranian government to fund a secret U.S. government apparatus that continued illegally to fund the Contras, in what became known as the Iran-Contra affair.[50] The U.S. continued to arm and train the Contras even after the Sandanista government of Nicaragua won the elections of 1984.[51][52]

- 1983 Grenada. In what the U.S. government called Operation Urgent Fury, the U.S. military invaded the tiny island nation of Grenada to remove the Marxist government of Grenada that the Reagan Administration found objectionable.[53][54] The United Nations General Assembly called the U.S. invasion "a flagrant violation of international law"[55] but a similar resolution widely supported in the United Nations Security Council was vetoed by the U.S.[56][57]

- 1989 Panama In December 1989, in a military operation code-named Operation Just Cause, the U.S. invaded Panama. President George H. W. Bush launched the war ten years after the Torrijos–Carter Treaties were ratified to transfer control of the Panama Canal from the United States to Panama by the year 2000.

- The U.S. deposed de facto Panamanian leader, general, and dictator Manuel Noriega and brought him to the United States, president-elect Guillermo Endara was sworn into office, and the Panamanian Defense Force was dissolved.

After the dissolution of the USSR

- 1991 Kuwait - The Persian Gulf War (2 August 1990 – 28 February 1991), codenamed Operation Desert Storm (17 January 1991 – 28 February 1991) commonly referred to as simply the Gulf War, was a war waged by a UN-authorized coalition force from 34 nations led by the United States, against Iraq in response to Iraq's invasion and annexation of Kuwait. The U.S. led coalition re-captured Kuwait from the Iraqi government and re-installed the authoritarian emir into power.[58]

- 1991 Haiti. Eight months after what was widely reckoned as the first honest election held in Haiti, the newly elected President Jean-Bertrand Aristide was deposed by the Haitian army. The CIA "paid key members of the coup regime forces, identified as drug traffickers, for information from the mid-1980s at least until the coup."[59] Coup leaders Cédras and François had received military training in the United States.[60]

.svg.png)

- 1994-96 Iraq. The CIA launched DBACHILLES, a coup d'état operation against the Iraqi government, recruiting Ayad Allawi, who headed the Iraqi National Accord, a network of Iraqis who opposed the Saddam Hussein government, as part of the operation. The network included Iraqi military and intelligence officers but was penetrated by people loyal to the Iraqi government.[61][62][63] Also using Ayad Allawi and his network, the CIA directed a government sabotage and bombing campaign in Baghdad between 1992 and 1995, against targets that—according to the Iraqi government at the time—killed many civilians including people in a crowded movie theater.[64] The CIA bombing campaign may have been merely a test of the operational capacity of the CIA's network of assets on the ground and not intended to be the launch of the coup strike itself.[64] The coup was unsuccessful, but Ayad Allawi was later installed as prime minister of Iraq by the Iraq Interim Governing Council, which had been created by the U.S.-led coalition following the invasion and occupation of Iraq.

.svg.png)

- Iran After 2003, news outlets reported that the U.S. was supporting Iranian opposition groups.[65][66][67][68] However, a later study of Iran–United States relations argued that while Israeli officials had proposed such "extreme measures," "Washington completely rejected these schemes."[69]

- 2005 Iran According to U.S. and Pakistani intelligence sources, beginning in 2005 the U.S. government secretly encouraged and advised a Pakistani Balochi militant group named Jundullah that is responsible for a series of deadly guerrilla raids inside Iran.[70] Jundullah, led by Abd el Malik Regi, sometimes known as "Regi," was suspected of being associated with al Qaida, a charge that the group has denied. ABC News learned from tribal sources that money for Jundullah was routed to the group through Iranian exiles. “They are suspected of having links to Al Qaeda and they are also thought to be tied to the drug culture," according to Professor Vali Nasr.[71] U.S. intelligence sources later claimed that the orchestration of Jundallah operations was, in actuality, an Israeli Mossad false flag operation that Israeli agents disguised to make it appear to be the work of American intelligence.[72]

- Syria 2005-2015 Starting in 2005, the US government launched a policy of regime change against the Syrian government by funding Syrian opposition groups working to topple the Syrian government, attempting to block foreign direct investment in Syria, attempting to frustrate Syrian government efforts at economic reform and prosperity and thus legitimacy for the regime, and getting other governments diplomatically to isolate Syria.[73] The Obama administration starting in 2009 continued such policies while taking steps toward diplomatic engagement with the Syrian government and denying that it was engaging in regime change. After the outbreak of the Syrian civil war, the U.S. government called on Syrian President Bashar Al Assad to “step aside” and imposed an oil embargo against the Syrian government to bring it to its knees.[74][75][76] Starting in 2013, the U.S. also provided training, weapons and cash to Syrian Islamic and secular insurgents fighting to topple the Syrian government.[77][78]

- 2011 Libya. The US was part of a multi-state coalition that began a military intervention in Libya to implement United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973, which was taken in response to events during the Libyan Civil War,[79] and military operations began, with US and British naval forces firing over 110 Tomahawk cruise missiles,[80] the French and British Air Forces[81] undertaking sorties across Libya and a naval blockade by Coalition forces.[82] Air strikes against Libyan Army tanks and vehicles by French jets were since confirmed.[83][84]

- 2006-2007 Palestinian Territories. In the Fatah-Hamas conflict, the U.S. government pressured the Fatah faction of the Palestinian leadership to topple the Hamas government of Prime Minister Ismail Haniyeh.[85][86][87] The Bush Administration was displeased with the government that the majority of the Palestinian people elected in the January Palestinian legislative election of 2006.[88][89][90][91] The U.S. government set up a secret training and armaments program that received tens of millions of dollars in Congressional funding, but also, like in the Iran-contra scandal, a more secret Congress-circumventing source of funding for Fatah to launch a bloody war against the Haniyeh government.[92][93][94] The war was brutal, with many casualties and with Fatah kidnapping and torturing civilian leaders of Hamas, sometimes in front of their own families, and setting fire to a university in Gaza. When the government of Saudi Arabia attempted to negotiate a truce between the sides so as to avoid a wide-scale Palestinian civil war, the U.S. government pressured Fatah to reject the Saudi plan and to continue the effort to topple the Faniyeh government.[95] Ultimately, the Faniyeh government was prevented from ruling over all of the Palestinian territories, with Hamas retreating to the Gaza strip and Fatah retreating to the West Bank.

Covert involvements

During the modern era, Americans were involved in numerous covert actions to support international regime change. During the Cold War era, American influence helped support change of regime in Syria in 1949, Iran in 1953, Guatemala in 1954, Brazil in 1964.

References

- ↑ United Nations Foundation, 20 August 2015, "The American Ratification of the UN Charter," http://unfoundationblog.org/the-american-ratification-of-the-un-charter/

- ↑ Mansell, Wade and Openshaw, Karen, "International Law: A Critical Introduction," Chapter 5, Hart Publishing, 2014, https://books.google.com/booksid=XYrqAwAAQBAJ&pg=PT140&lpg=PT140&dq=UN+Charter+the+preeminent+international+law+document&source=bl&ots=TTZu8OAN0b&sig=NvzfkKx32FiLphBbjOJUbvNPNlc&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiKl8Oq9ofQAhWJ7oMKHSljBioQ6AEINTAF#v=onepage&q=UN%20Charter%20the%20preeminent%20international%20law%20document&f=false

- ↑ "All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state." United Nations, "Charter of the United Nations," Article 2(4), http://www.un.org/en/sections/un-charter/chapter-i/index.html

- ↑ Fox, Gregory, "Regime Change," 2013, Oxford Public International Law, Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, Sections C(12) and G(53)-(55), http://opil.ouplaw.com/view/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e1707

- ↑ Stevenson, Robert Louis (1892). A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 1-4264-0754-8.

- ↑ Ryden, George Herbert. The Foreign Policy of the United States in Relation to Samoa. New York: Octagon Books, 1975. (Reprint by special arrangement with Yale University Press. Originally published at New Haven: Yale University Press, 1928), p. 574; the Tripartite Convention (United States, Germany, Great Britain) was signed at Washington on 2 December 1899.

- ↑ Ryden, George Herbert. The Foreign Policy of the United States in Relation to Samoa. New York: Octagon Books, 1975. (Reprint by special arrangement with Yale University Press. Originally published at New Haven: Yale University Press, 1928), p. 574; the Tripartite Convention (United States, Germany, Great Britain) was signed at Washington on 2 December 1899 with ratifications exchanged on 16 February 1900

- ↑ Kalaw 1927, pp. 199–200

- ↑ Worcester 1914, p. pageno=180 180

- ↑ Spence, In Search of Modern China, pp. 230–235; Keith Schoppa, Revolution and Its Past, pp. 118–123.

- ↑ In a state speech in December 1903, President Roosevelt put the number of "revolutions, rebellions, insurrections, riots, and other outbreaks" in Panama at 53, within the space of 57 years. in "Theodore Roosevelt's third state of the union address":http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Theodore_Roosevelt%27s_Third_State_of_the_Union_Address

- ↑ http://www2.truman.edu/~marc/resources/interventions.html

- ↑ GILES A. HUBERT, WAR AND THE TRADE ORIENTATION OF HAITI, http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/1053341.pdf

- ↑ Coatsworth, John. H. "Central America and the United States: The Clients and the Colossus," Twayne Publishers, New York:1994, pages 45 and 225

- ↑ The date of the coup in the Persian calendar.

- ↑ CLANDESTINE SERVICE HISTORY: OVERTHROW OF PREMIER MOSSADEQ OF IRAN, Mar. 1954: p iii.

- ↑ Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez, and Decolonization. I.B.Tauris. 2007. pp. 775 of 1082. ISBN 9781845113476.

- ↑ New York Times, 2000, "Secrets of History: The United States in Iran," http://www.nytimes.com/library/world/mideast/041600iran-cia-index.html

- ↑ U.S. foreign policy in perspective: clients, enemies and empire. David Sylvan, Stephen Majeski, p.121.

- ↑ Coatsworth, John. H. "Central America and the United States: The Clients and the Colossus," Twayne Publishers, New York:1994, pages 58 and 226

- ↑ Kornbluh, Peter; Doyle, Kate, eds. "CIA and Assassinations: The Guatemala 1954 Documents", National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book overview, Washington, D.C.: National Security Archive, http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB4/index.html

- ↑ Kornbluh, Peter; Doyle, Kate, eds. "CIA and Assassinations: The Guatemala 1954 Documents", National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book Document 5, Washington, D.C.: National Security Archive, http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB4/index.html

- ↑ Office of the Historian, United States Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961-63, Volume X, Cuba, January 1961–September 1962, “291. Program Review by the Chief of Operations, Operation Mongoose (Lansdale),” January 18, 1962, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v10/d291

- ↑ Office of the Historian, United States Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961-63, Volume X, Cuba, January 1961–September 1962, “291. Program Review by the Chief of Operations, Operation Mongoose (Lansdale),” January 18, 1962, pages 711-17, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v10/d291

- ↑ Domínguez, Jorge I. "The @#$%& Missile Crisis (Or, What was 'Cuban' about US Decisions during the Cuban Missile Crisis),” Diplomatic History: The Journal of the Society for Historians of Foreign Relations, Vol. 24, No. 2, Spring 2000: 305–15

- ↑ Office of the Historian, United States Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961-63, Volume X, Cuba, January 1961–September 1962, “291. Program Review by the Chief of Operations, Operation Mongoose (Lansdale),” January 18, 1962, pages 711-17, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v10/d291

- ↑ NBC News, 26 June 2007, “CIA Acknowledges Castro Plot Went All the Way to the Top, Dulles Personally Approved 1960 Operation to Assassinate Castro,” http://www.nbcnews.com/id/19444072/ns/politics/t/cia-acknowledges-castro-plot-went-top/#.WBq8i4XfjvY

- ↑ Escalante Font, Fabián, “Executive Action: 634 Ways to Kill Fidel Castro,” Melbourne: Ocean Press, 2006

- ↑ The Guardian, 2 August 2006, “638 ways to kill Castro,” https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/aug/03/cuba.duncancampbell2

- ↑ Stephen G. Rabe, "The Johnson Doctrine", Presidential Studies Quarterly 36

- ↑ "Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968 Volume XXXII, Dominican Republic; Cuba; Haiti; Guyana, Document 43". US Dept. of State. Retrieved 2011-04-26.

- ↑ Peter Kornbluh. "Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973".

- ↑ Valech Report

- ↑ Gómez-Barris, Macarena (2010). "Witness Citizenship: The Place of Villa Grimaldi in Chilean Memory". Sociological Forum. 25 (1): 34. doi:10.1111/j.1573-7861.2009.01155.x.

- ↑ "El campo de concentración de Pinochet cumple 70 años". El País. 3 December 2008.

- ↑ "Chile President Pinera to ask Obama for Pinochet files". BBC News. 23 March 2011.

- ↑ Washington Post, 27 December 2007, "Sorry Charlie This is Michael Vickers's War," http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/12/27/AR2007122702116.html

- ↑ Riedel, Bruce 2014, "What We Won: America's Secret War in Afghanistan, 1979–1989," Brookings Institution Press. pp. ix–xi, 21–22, 98–105

- ↑ Newsweek, 1 October 2001, Evan Thomas, "The Road to September 11," http://www.newsweek.com/war-terror-road-september-11-151771

- ↑ Crile, George (2003) "Charlie Wilson's War: The Extraordinary Story of the Largest Covert Operation in History," Atlantic Monthly Press, page 519

- ↑ National Security Decision Directive 17 (NSD-17), January 1982, https://fas.org/irp/offdocs/nsdd/nsdd-17.pdf

- ↑ Presidential Finding authorizing paramilitary activities, December 1981, http://www.brown.edu/Research/Understanding_the_Iran_Contra_Affair/documents/d-all-45.pdf

- ↑ New York Times, 22 February 1985, “President Asserts Goal Is to Remove Sandanista Regime,” http://www.nytimes.com/1985/02/22/us/president-asserts-goal-is-to-remove-sandinista-regime.html

- ↑ Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium, "Contras," http://www.trackingterrorism.org/group/contras

- ↑ Facts on File World News Digest, 19 October 1984, “U.S. Orders Probe of CIA Terror Manual,” archived at Live Journal: http://bailey83221.livejournal.com/60879.html#2c

- ↑ Woodward, Bob, “Veil, The Secret Wars of the CIA,” 1987 New York: Simon & Schuster

- ↑ Gilbert, Dennis, “Sandinistas: The Party and The Revolution,” Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1988, pp 167

- ↑ Los Angeles Times, 5 March 1986, “Setback for Contras : CIA Mining of Harbors 'a Fiasco,’” http://articles.latimes.com/1985-03-05/news/mn-12633_1_harbor-mining

- ↑ International Court of Justice, NICARAGUA v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, 27 June 1986, http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/?sum=367&p1=3&p2=3&case=70&p3=5

- ↑ New York Times, 10 July 1987, “Iran-Contra Hearings; Boland Amendments: What They Provided,” http://www.nytimes.com/1987/07/10/world/iran-contra-hearings-boland-amendments-what-they-provided.html

- ↑ BBC News, 27 June 1986, "BBC ON THIS DAY - 5 - 1984: Sandinistas claim election victory,"http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/june/27/newsid_2520000/2520169.stm

- ↑ New York Times, 16 November 1984, "NICARAGUAN VOTE: 'FREE, FAIR, HOTLY CONTESTED,'" http://www.nytimes.com/1984/11/16/opinion/l-nicaraguan-vote-free-fair-hotly-contested-089345.html

- ↑ New York Times, 30 March 1984, "Medals Outnumber G.I.s in Grenada Assault," http://www.nytimes.com/1984/03/30/world/medals-outnumber-gi-s-in-grenada-assault.html

- ↑ Stuart, Richard W., 2008, "Operation Urgent Fury: The Invasion of Grenada, October 1983" U.S. Army, http://www.history.army.mil/html/books/grenada/urgent_fury.pdf

- ↑ United Nations General Assembly Resolution 38/7, 2 November 1983, http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/38/7

- ↑ Global Policy Forum, Foreign Policy in Focus, Zunes, Stephen, October 2003, "The U.S. Invasion of Grenada: A Twenty Year Retrospective," https://www.globalpolicy.org/component/content/article/155/25966.html

- ↑ United Nations Security Council vetoes, 28 October 1983, http://research.un.org/en/docs/sc/quick/

- ↑ New York Times, 15 March 1991, "After the War: Kuwait; Kuwaiti Emir, Tired and Tearful, Returns to His Devastated Land," http://www.nytimes.com/1991/03/15/world/after-war-kuwait-kuwaiti-emir-tired-tearful-returns-his-devastated-land.html

- ↑ Whitney, Kathleen Marie (1996). "Sin, Fraph, and the CIA: U.S. Covert Action in Haiti". Southwestern Journal of Law and Trade in the Americas. 3 (2): 303–332 [p. 320].

- ↑ Whitney 1996, p. 321

- ↑ Association of Former Intelligence Officers (19 May 2003), US Coup Plotting in Iraq, Weekly Intelligence Notes 19-03

- ↑ Washington Post, 16 May 16, 2003, "The CIA And the Coup That Wasn't," The CIA And the Coup That Wasn't, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/2003/05/16/the-cia-and-the-coup-that-wasnt/0abfb8fa-61e9-4159-a885-89b8c476b188/?utm_term=.e07941c00e73

- ↑ Washington Post, 23 June 1996 “With CIA's Help, Group in Jordan Targets Saddam; U.S. Funds Support Campaign To Topple Iraqi Leader From Afar,” http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/washingtonpost/doc/307963286.html?FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&date=Jun+23%2C+1996&author=Lancaster%2C+John%7C%7C%7C%7C%7C%7COttaway%2C+David+B&desc=With+CIA%27s+Help%2C+Group+in+Jordan+Targets+Saddam%3B+U.S.+Funds+Support+Campaign+To+Topple+Iraqi+Leader+From+Afar

- 1 2 "The Iraqi government at the time claimed that the bombs, including one it said exploded in a movie theater, resulted in many civilian casualties ... One former Central Intelligence Agency officer who was based in the region, Robert Baer, recalled that a bombing during that period 'blew up a school bus; schoolchildren were killed.' Mr. Baer ... said he did not recall which resistance group might have set off that bomb. Other former intelligence officials said Dr. Allawi's organization was the only resistance group involved in bombings and sabotage at that time. But one former senior intelligence official recalled that 'bombs were going off to no great effect.' 'I don't recall very much killing of anyone,' the official said." New York Times, 9 June 2004, "Ex-C.I.A. Aides Say Iraq Leader Helped Agency in 90's Attacks," http://www.nytimes.com/2004/06/09/world/reach-war-new-premier-ex-cia-aides-say-iraq-leader-helped-agency-90-s-attacks.html

- ↑ ABC News, “The Blotter Blog,” Brian Ross; Christopher Isham (2007-04-03), "Exclusive: The Secret War Against Iran," http://blogs.abcnews.com/theblotter/2007/04/abc_news_exclus.html

- ↑ The New Yorker, Seymour M. Hirsch (2006-11-20), "The Next Act," http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2006/11/27/the-next-act

- ↑ The New Yorker, 8 July 2008, Seymour Hersh, "Preparing the Battlefield, The Bush Administration Steps Up Its Secret Moves Against Iran," http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/07/07/preparing-the-battlefield

- ↑ A high level government policy memorandum written after September 11, 2001, outlined a list of military actions to be undertaken against Iran and some other countries. Inter Press Service, May 5, 2008, "Pentagon Targeted Iran for Regime Change after 9/11," http://ipsnorthamerica.net/news.php?idnews=1446 also archived at http://www.commondreams.org/archive/2008/05/06/8741/

- ↑ Crist, David (2013). The Twilight War: The Secret History of America's Thirty-Year Conflict with Iran. Penguin Group. p. 550. ISBN 9780143123675.

- ↑ ABC News, “The Blotter Blog,” Brian Ross; Christopher Isham (2007-04-03), "Exclusive: The Secret War Against Iran," http://blogs.abcnews.com/theblotter/2007/04/abc_news_exclus.html

- ↑ The New Yorker, 8 July 2008, Seymour Hersh, "Preparing the Battlefield, The Bush Administration Steps Up Its Secret Moves Against Iran," http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/07/07/preparing-the-battlefield

- ↑ Foreign Policy, 13 January 2012, "False Flag," http://foreignpolicy.com/2012/01/13/false-flag/

- ↑ Truthout, 9 October 2015, “WikiLeaks Reveals How the US Aggressively Pursued Regime Change in Syria, Igniting a Bloodbath,” http://www.truth-out.org/progressivepicks/item/33180-wikileaks-reveals-how-the-us-aggressively-pursued-regime-change-in-syria-igniting-a-bloodbath, citing Chapter 10 of the book “The WikiLeaks Files,” Naiman, Robert, Verso Books

- ↑ Council on Foreign Relations, 18 August 2014, “Calling for Regime Change in Syria,” http://www.cfr.org/syria/calling-regime-change-syria/p25677

- ↑ The Wall Street Journal, 11 August 2014, “World Leaders Urge Assad to Resign: Obama Imposes New Embargo on Syrian Oil Sales as Europe Considers Similar Measures; Crackdown on Protests Persists,” http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424053111903639404576516144145940136

- ↑ The Guardian, 15 January 2015, “US Changes Its Tune on Syrian Regime Change as Isis Threat Takes Top Priority, Washington Still Hopes Bashar al-Assad Will Be Removed from Power, But Is No Longer Insisting on It As A Precondition for Peace, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/jan/25/us-syrian-regime-change-isis-priority

- ↑ National Public Radio, 23 April 2014, “CIA Is Quietly Ramping Up Aid To Syrian Rebels, Sources Say,” http://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2014/04/23/306233248/cia-is-quietly-ramping-up-aid-to-syrian-rebels-sources-say

- ↑ The Guardian, 8 March 2013, “West Training Syrian Rebels in Jordan Exclusive: UK and French Instructors Involved in US-Led Effort to Strengthen Secular Elements in Syria's Opposition, Say Sources,” https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/mar/08/west-training-syrian-rebels-jordan

- ↑ "Security Council Approves 'No-Fly Zone' over Libya, Authorizing 'All Necessary Measures' To Protect Civilians in Libya, by a Vote of Ten For, None Against, with Five Abstentions". United Nations. 17 March 2011. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ↑ "Libya Live Blog – March 19". Al Jazeera. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ↑ "Libya: US, UK and France attack Gaddafi forces". BBC News. 20 March 2011. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ↑ "French Fighter Jets Deployed over Libya". CNN. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 22 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ↑ "France Uses Unexplosive Bombs in Libya: Spokesman". Xinhua News Agency. 29 April 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ↑ Gibson, Ginger (8 April 2011). "Polled N.J. Voters Back Obama's Decision To Establish No-Fly Zone in Libya". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ↑ Vanity Fair, 3 March 2008, “The Gaza Bombshell,” http://www.vanityfair.com/news/2008/04/gaza200804

- ↑ Christian Science Monitor, 25 May 2007, “Israel, US, and Egypt Back Fatah's Fight Against Hamas,” http://www.csmonitor.com/2007/0525/p07s02-wome.html

- ↑ The Times (UK), 18 November 2006, Diplomats Fear US wants to Arm Fatah for 'War on Hamas'

- ↑ Vanity Fair, 3 March 2008, “The Gaza Bombshell,” http://www.vanityfair.com/news/2008/04/gaza200804

- ↑ Christian Science Monitor, 25 May 2007, “Israel, US, and Egypt Back Fatah's Fight Against Hamas,” http://www.csmonitor.com/2007/0525/p07s02-wome.html

- ↑ The Times (UK), 18 November 2006, "Diplomats Fear US Wants to Arm Fatah for 'War on Hamas'

- ↑ In fact, some, like Senator Hillary Clinton suggested that "I do not think we should have pushed for an election in the Palestinian territories. I think that was a big mistake. And if we were going to push for an election, then we should have made sure that we did something to determine who was going to win." Russia Today, 29 October 2016, "Clinton Bemoans US Not Rigging 2006 Palestinian Election in Newly-Released Tape," https://www.rt.com/usa/364628-clinton-rigging-palestine-tape/

- ↑ Vanity Fair, 3 March 2008, “The Gaza Bombshell,” http://www.vanityfair.com/news/2008/04/gaza200804

- ↑ The Middle East Online, 31 January 2007, http://www.middle-east-online.com/english/?id=19358

- ↑ San Francisco Chronicle, 14 December 2006, "U.S. Training Fatah in Anti-Terror Tactic--Underlying Motive Is to Counter Strength of Hamas, Analysts Say," http://www.sfgate.com/news/article/U-S-training-Fatah-in-anti-terror-tactics-2465370.php

- ↑ Vanity Fair, 3 March 2008, “The Gaza Bombshell,” http://www.vanityfair.com/news/2008/04/gaza200804

Bibliography

- Bass, Gary (2008). Freedom's Battle: The Origins of Humanitarian Intervention. Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 9780307269294.

- Bert, Wayne (2016). American Military Intervention in Unconventional War: From the Philippines to Iraq. Springer. ISBN 9780230337817.

- Blum, William (2003). Killing Hope: US Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II. Zed Books. ISBN 9781842773697.

- Bruzzese, Anthony (2008). The Origins of Intervention: America, Italy, and the Fight Against Communism, 1947-1953. ISBN 9780494469521.

- Cooley, Alexander (2012). Great Games, Local Rules: The New Power Contest in Central Asia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199812004.

- Cullinane, Michael (2012). Liberty and American Anti-Imperialism: 1898-1909. Springer. ISBN 9781137002570.

- Foner, Philip (1972). The Spanish-Cuban-American War and the Birth of American Imperialism Vol. 1: 1895–1898. NYU Press. ISBN 9780853452669.

- Foner, Philip (1972). The Spanish-Cuban-American War and the Birth of American Imperialism Vol. 2: 1898–1902. NYU Press. ISBN 9780853452676.

- Fouskas, Vassilis; Gökay, Bülent (2005). The New American Imperialism: Bush's War on Terror and Blood for Oil. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780275984762.

- Grow, Michael (2008). U.S. Presidents and Latin American Interventions: Pursuing Regime Change in the Cold War. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700615865.

- Harland, Michael (2013). Democratic Vanguardism: Modernity, Intervention, and the Making of the Bush Doctrine. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739179703.

- Hiro, Dilip (2014). War Without End: The Rise of Islamist Terrorism and Global Response. Routledge. ISBN 9781136485565.

- Little, Douglass (2009). American Orientalism: The United States and the Middle East since 1945. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807877616.

- Little, Douglass (2016). Us versus Them: The United States, Radical Islam, and the Rise of the Green Threat. UNC Press Books. ISBN 9781469626819.

- Maurer, Noel (2013). The Empire Trap: The Rise and Fall of U.S. Intervention to Protect American Property Overseas, 1893-2013. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400846603.

- McPherson, Alan (2016). A Short History of U.S. Interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118954003.

- McPherson, Alan (2013). Encyclopedia of U.S. Military Interventions in Latin America. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598842609.

- North, David (2016). A Quarter Century of War. Mehring Books. ISBN 9781893638693.

- Parmar, Inderjeet; Cox, Michael (2010). Soft Power and US Foreign Policy: Theoretical, Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 9781135150488.

- Sandstrom, Karl. Local Interests and American Foreign Policy: Why International Interventions Fail. Routledge. ISBN 9781135041656.

- Schoonover, Thomas (2013). Uncle Sam's War of 1898 and the Origins of Globalization. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813143361.

- Sullivan, Michael (2008). American adventurism abroad: invasions, interventions, and regime changes since World War II. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 9781405170758.

- Wilford, Hugh (2008). The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA Played America. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674045170.

- Wilford, Hugh (2013). America's Great Game: The CIA's Secret Arabists and the Shaping of the Modern Middle East. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465019656.