Cordelia (moon)

|

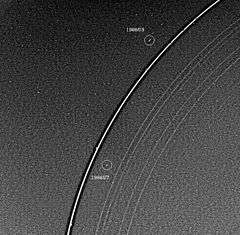

Cordelia (lower-middle, inside of bright ring), discovery image from Voyager 2 | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Richard J. Terrile / Voyager 2 |

| Discovery date | January 20, 1986 |

| Orbital characteristics | |

Mean orbit radius | 49751.722 ± 0.149 km[1] |

| Eccentricity | 0.00026 ± 0.000096[1] |

| 0.33503384 ± 0.00000058 d[1] | |

| Inclination | 0.08479 ± 0.031° (to Uranus' equator)[1] |

| Satellite of | Uranus |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 50 × 36 × 36 km[2] |

Mean radius | 20.1 ± 3 km[2][3][4] |

| ~5500 km²[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Volume | ~38,900 km³[lower-alpha 1] |

| Mass | ~4.4×1016 kg[lower-alpha 1] |

Mean density | ~1.3 g/cm³ (assumed)[3] |

| ~0.0073 m/s²[lower-alpha 1] | |

| ~0.017 km/s[lower-alpha 1] | |

| synchronous[2] | |

| zero[2] | |

| Albedo | |

| Temperature | ~64 K[lower-alpha 1] |

|

| |

Cordelia (/kɔːrˈdiːliə/ kor-DEE-lee-ə) is the innermost known moon of Uranus. It was discovered from the images taken by Voyager 2 on January 20, 1986, and was given the temporary designation S/1986 U 7.[6] It was not detected again until the Hubble Space Telescope observed it in 1997.[5][7] Cordelia takes its name from the youngest daughter of Lear in William Shakespeare's King Lear. It is also designated Uranus VI.[8]

Other than its orbit,[1] radius of 20 km[2] and geometric albedo of 0.08[5] virtually nothing is known about it. In the Voyager 2 images Cordelia appears as an elongated object with its major axis pointing towards Uranus. The ratio of axes of Cordelia's prolate spheroid is 0.7 ± 0.2.[2]

Cordelia acts as the inner shepherd satellite for Uranus' Epsilon ring.[9] Cordelia's orbit is within Uranus' synchronous orbit radius, and is therefore slowly decaying due to tidal deceleration.[2]

Cordelia is very close to a 5:3 orbital resonance with Rosalind.[10]

See also

References

Explanatory notes

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jacobson, R. A. (1998). "The Orbits of the Inner Uranian Satellites From Hubble Space Telescope and Voyager 2 Observations". The Astronomical Journal. 115 (3): 1195–1199. Bibcode:1998AJ....115.1195J. doi:10.1086/300263.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Karkoschka, Erich (2001). "Voyager's Eleventh Discovery of a Satellite of Uranus and Photometry and the First Size Measurements of Nine Satellites". Icarus. 151 (1): 69–77. Bibcode:2001Icar..151...69K. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6597.

- 1 2 3 "Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters". JPL (Solar System Dynamics). 24 October 2008. Retrieved 12 December 2008.

- 1 2 Williams, Dr. David R. (23 November 2007). "Uranian Satellite Fact Sheet". NASA (National Space Science Data Center). Retrieved 12 December 2008.

- 1 2 3 Karkoschka, Erich (2001). "Comprehensive Photometry of the Rings and 16 Satellites of Uranus with the Hubble Space Telescope". Icarus. 151 (1): 51–68. Bibcode:2001Icar..151...51K. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6596.

- ↑ Smith, B. A. (1986-01-27). "Satellites and Rings of Uranus". IAU Circular. 4168. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ Showalter, M. R.; Lissauer, J. J. (2003-09-03). "Satellites of Uranus". IAU Circular. 8194. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ "Planet and Satellite Names and Discoverers". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology. July 21, 2006. Retrieved 6 August 2006.

- ↑ Esposito, L. W. (2002). "Planetary rings". Reports On Progress In Physics. 65 (12): 1741–1783. Bibcode:2002RPPh...65.1741E. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/65/12/201.

- ↑ Murray, Carl D.; Thompson, Robert P. (1990-12-06). "Orbits of shepherd satellites deduced from the structure of the rings of Uranus". Nature. 348 (6301): 499–502. Bibcode:1990Natur.348..499M. doi:10.1038/348499a0. ISSN 0028-0836.