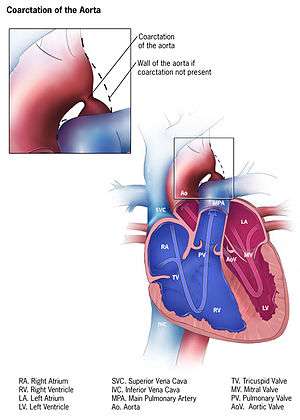

Coarctation of the aorta

| Aortic coarctation | |

|---|---|

| |

| Illustration of an aortic coarctation | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Cardiac surgery |

| ICD-10 | Q25.1 |

| ICD-9-CM | 747.10 |

| OMIM | 120000 |

| DiseasesDB | 2876 |

| MedlinePlus | 000191 |

| eMedicine | med/154 |

| Patient UK | Coarctation of the aorta |

| MeSH | D001017 |

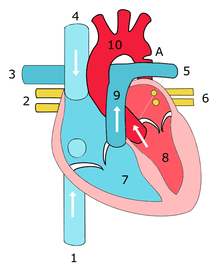

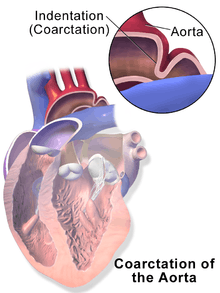

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA[1][2] or CoAo), also called aortic narrowing, is a congenital condition whereby the aorta is narrow, usually in the area where the ductus arteriosus (ligamentum arteriosum after regression) inserts. The word “coarctation” means narrowing. Coarctations are most common in the aortic arch. The arch may be small in babies with coarctations. Other heart defects may also occur when coarctation is present, typically occurring on the left side of the heart. When a patient has a coarctation, the left ventricle has to work harder. Since the aorta is narrowed, the left ventricle must generate a much higher pressure than normal in order to force enough blood through the aorta to deliver blood to the lower part of the body. If the narrowing is severe enough, the left ventricle may not be strong enough to push blood through the coarctation, thus resulting in lack of blood to the lower half of the body. Physiologically its complete form is manifested as interrupted aortic arch.

Classification

There are three types of aortic coarctations:[3]

- Preductal coarctation: The narrowing is proximal to the ductus arteriosus. Blood flow to the aorta that is distal to the narrowing is dependent on the ductus arteriosus; therefore severe coarctation can be life-threatening. Preductal coarctation results when an intracardiac anomaly during fetal life decreases blood flow through the left side of the heart, leading to hypoplastic development of the aorta. This is the type seen in approximately 5% of infants with Turner syndrome.[4][5]

- Ductal coarctation: The narrowing occurs at the insertion of the ductus arteriosus. This kind usually appears when the ductus arteriosus closes.

- Postductal coarctation: The narrowing is distal to the insertion of the ductus arteriosus. Even with an open ductus arteriosus, blood flow to the lower body can be impaired. This type is most common in adults. It is associated with notching of the ribs (because of collateral circulation), hypertension in the upper extremities, and weak pulses in the lower extremities. Postductal coarctation is most likely the result of the extension of a muscular artery (ductus arteriosus) into an elastic artery (aorta) during fetal life, where the contraction and fibrosis of the ductus arteriosus upon birth subsequently narrows the aortic lumen.[6]

Aortic coarctation and aortic stenosis are both forms of aortic narrowing. In terms of word root meanings, the names are not different, but a conventional distinction in their usage allows differentiation of clinical aspects. This spectrum is dichotomized by the idea that aortic coarctation occurs in the aortic arch, at or near the ductus arteriosis, whereas aortic stenosis occurs in the aortic root, at or near the aortic valve. This naturally could present the question of the dividing line between a postvalvular stenosis and a preductal coarctation; nonetheless, the dichotomy has practical use, as most defects are either one or the other.

Signs and symptoms

In mild cases, children may show no signs or symptoms at first and their condition may not be diagnosed until later in life. Some children born with coarctation of the aorta have other heart defects too, such as aortic stenosis, ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus or mitral valve abnormalities.

Coarctation is about twice as common in boys as it is in girls. It is common in girls who have Turner syndrome.

Symptoms may be absent with mild narrowings (coarctation). When present, they include: difficulty breathing, poor appetite or trouble feeding, failure to thrive. Later on, children may develop symptoms related to problems with blood flow and an enlarged heart. They may experience dizziness or shortness of breath, faint or near-fainting episodes, chest pain, abnormal tiredness or fatigue, headaches, or nosebleeds. They have cold legs and feet or have pain in their legs with exercise (intermittent claudication).

In more severe cases, where severe coarctations, babies may develop serious problems soon after birth because not enough blood can get through the aorta to the rest of their body. Arterial hypertension in the arms with low blood pressure in the lower extremities is classic. In the lower extremities, weak pulses in the femoral arteries and arteries of the feet are found.

The coarctation typically occurs after the left subclavian artery. However, if situated before it, blood flow to the left arm is compromised and asynchronous or radial pulses of different "strength" may be detected (normal on the right arm, weak or delayed on the left). In these cases, a difference between the normal radial pulse in the right arm and the delayed femoral pulse in the legs (either side) may be apparent, whilst no such delay would be appreciated with palpation of both delayed left arm and either femoral pulses. On the other hand, a coarctation occurring after the left subclavian artery will produce synchronous radial pulses, but radial-femoral delay will be present under palpation in either arm (both arm pulses are normal compared to the delayed leg pulses).

Diagnosis

With imaging, resorption of the lower part of the ribs may be seen, due to increased blood flow over the neurovascular bundle that runs there. Poststenotic dilatation of the aorta results in a classic 'figure 3 sign' on x-ray. The characteristic bulging of the sign is caused by dilatation of the aorta due to an indrawing of the aortic wall at the site of cervical rib obstruction, with consequent poststenotic dilatation. This physiology results in the '3' image for which the sign is named.[7][8][9] When the esophagus is filled with barium, a reverse 3 or E sign is often seen and represents a mirror image of the areas of prestenotic and poststenotic dilatation.[10]

Coarctation of the aorta can be accurately diagnosed with magnetic resonance angiography. In teenagers and adults echocardiograms may not be conclusive. In adults with untreated coarctation, blood often reaches the lower body through collaterals, e.g. internal thoracic arteries via the subclavian arteries. Those can be seen on MR, CT or angiography. An untreated coarctation may also result in hypertrophy of the left ventricle.

Arteries can be checked for narrowing by the cardiologist by using an CT angiogram. This test is very easy on the patient because it is a minimally invasive procedure. The first step in the process is having a dye injected into the patient to help highlight the arteries for the CT scanner. While the CT scanner is imaging the arteries, images will be able to be viewed by the cardiologists almost immediately.

An MRI scan is a test that uses a magnetic field and pulses of radio wave energy to make pictures of the body. An MRI of your chest will reveal the location of the coarctation of the aorta and determine whether it affects other blood vessels in the body.

Cardiac catheterization is an invasive imaging procedure that is a tool for evaluating heart functions in real time. A long, narrow tube called a catheter is inserted through a plastic hollow tube called an introducer sheath. The introducer sheath is typically inserted into the patients arm or leg. The catheter is positioned through the patients blood vessel until it reaches the coronary arteries. Once the catheter is in position, a contrast dye is injected though the tip of the catheter while x-rays are taken to follow the dye through the chambers of the heart and arteries. This part of the procedure is called the coronary angiogram. Coronary artery disease (CAD) occurs when there is a narrowing or blockage of the arteries leading to or from the heart. The cardiac catheterization is an interventional procedure that opens up the coronary artery to increase the blood flow to the heart. The contrast material injected into the arteries that help produce images of the heart help locate narrowed or blocked areas in arteries around the heart. There are other ways to produce images such as intra-vascular ultrasound (IVUS) and fractional flow reserve. These two different procedures give cardiologists more diverse options to best suit the patients needs.

Aortic coarctation using different imaging techniques[11]

Aortic coarctation using different imaging techniques[11]

Treatment

Treatment is conservative if asymptomatic, but may require surgical resection of the narrow segment if there is arterial hypertension. The first operations to treat coarctation were carried out by Clarence Crafoord in Sweden in 1944.[12] In some cases angioplasty can be performed to dilate the narrowed artery.

For fetuses at high risk for developing coarctation, a novel experimental treatment approach is being investigated, wherein the mother inhales 45% oxygen three times a day (3 x 3–4 hours) beyond 34 weeks of gestation. The oxygen is transferred via the placenta to the fetus and results in dilatation of the fetal lung vessels. As a consequence, the flow of blood through the fetal circulatory system increases, including that through the underdeveloped arch. In suitable fetuses, marked increases in aortic arch dimensions have been observed over treatment periods of about two to three weeks.[13]

The long term outcome is very good. Some patients may, however, develop narrowing (stenosis) or dilatation at the previous coarctation site. All patients with unrepaired or repaired aortic coarctation require follow up in specialized Congenital Heart Disease centers.

Complications of surgery

Surgical treatment involves resection of the stenosed segment and re-anastomsis. Two complications specific to this surgery are Left recurrent nerve palsy and chylothorax, as the recurrent laryngeal nerve and thoracic duct are in the vicinity. Chylothorax is a troublesome complication and is usually managed conservatively by adjusting the diet to eliminate long chain fatty acids and supplementing medium chain triglycerides. When conservative management fails surgical intervention is required.[14] Fluorescein dye can aid in the localisation of chyle leak.[15]

Prognosis

Side effects

Hypertension is defined when a patient's blood pressure in the arm exceeds 140/90 mmHg under normal conditions. This is a severe problem for the heart and can cause many other complications. In a study of 120 coarctation repair recipients done in Groningen, The Netherlands, twenty-nine patients (25%) experienced hypertension in the later years of life due to the repair. While hypertension has many different factors that lead to this stage of blood pressure, people who have had a coarctation repair — regardless of the age at which the operation was performed — are at much higher risk than the general public of hypertension later in life. Undetected chronic hypertension can lead to sudden death among coarctation repair patients, at higher rates as time progresses.

Angioplasty is a procedure done to dilate an abnormally narrow section of a blood vessel to allow better blood flow. This is done in a cardiac catheterization laboratory. Typically taking two to three hours, the procedure may take longer but usually patients are able to leave the hospital the same day. After a coarctation repair 20-60% of infant patients may experience reoccurring stenosis at the site of the original operation. This can be fixed by either another coarctectomy.[16]

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a major issue for patients who have undergone a coarctation repair. Many years after the procedure is done, heart disease not only has an increased chance of affecting coarctation patients, but also progresses through the levels of severity at an alarmingly increased rate. In a study conducted by Mare Cohen, MD, et al., one fourth of the patients who experienced a coarctation died of heart disease, some at a relatively young age.[17][18]

Clinical criteria are used in most studies when defining recurrence of coarctation (recoarctation) when blood pressure is at a difference of >20 mmHg between the lower and upper limbs. This procedure is most common in infant patients and is uncommon in adult patients. In a study conducted by Koller et al., 10.8% of infant patients underwent recoarctations at less than two years of age while another 3.1% of older children received a recoarctation.[19]

People who have had a coarctation of the aorta are likely to have bicuspid aortic valve disease. Between 20% and 85% of patients are affected with this disease. Bicuspid aortic valve disease is a big contributor to cardiac failure, which in turn makes up roughly 20% of late deaths to coarctation patients.[19]

Follow-up

Leaving the hospital after a coarctation procedure is only one step in a lifelong process. Just because the coarctation was fixed does not mean that the patient is cured. It is extremely important to visit the cardiologist on a regular basis. Depending on the severity of the patient's condition, which is evaluated on a case-by-case level, visiting a cardiologist can be a once a year surveillance check up. Keeping a regular schedule of appointments with a cardiologist after a coarctation procedure is complete helps increase the chances of survivability for the patients.[20]

Prevention

Unfortunately, coarctations can not be prevented because they are usually present at birth. The best thing for patients who are affected by coarctations is early detection. Some signs that can lead to a coarctation have been linked to pathologies such as Turner syndrome, bicuspid aortic valve, and other family heart conditions.

History

An anecdotal history statement describes the first diagnosed case of the coarctation of the aorta in Julia the daughter of the French poet Alphonse de Lamartine after the autopsy in 1832 in Beirut, the reference manuscript still exists in one of the Maronite monasteries in Mount Lebanon.

References

- ↑ "Coarctation of the Aorta (CoA)". heart.org.

- ↑ Groenemeijer, BE; Bakker, A; Slis, HW; Waalewijn, RA; Heijmen, RH (2008). "An unexpected finding late after repair of coarctation of the aorta". Netherlands Heart Journal. 16 (7-8): 260–3. PMC 2516290

. PMID 18711614.

. PMID 18711614. - ↑ Valdes-Cruz, Lilliam M.; Cayre, Raul O., eds. (1999). Echocardiographic Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease: An Embryologic and Anatomic Approach. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-1433-4.

- ↑ Cotran, R.; V. Kumar & N. Fausto (2005). Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease (7th ed.). W.B. Saunders. ISBN 0-8089-2302-1.

- ↑ Völkl, Thomas M. K.; Degenhardt, Karin; Koch, Andreas; Simm, Diemud; Dörr, Helmuth G.; Singer, Helmut (2005). "Cardiovascular anomalies in children and young adults with Ullrich-Turner syndrome-the erlangen experience". Clinical Cardiology. 28 (2): 88–92. doi:10.1002/clc.4960280209. PMID 15757080.

- ↑ Surgical Approach to Coarctation of the Aorta and Interrupted Aortic Arch at eMedicine

- ↑ Brant, William E.; Helms, Clyde A., eds. (2012). "Coarctation of the aorta". Fundamentals of Diagnostic Radiology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1172. ISBN 978-1-60831-911-4.

- ↑ Blecha, Matthew J. (August 30, 2005). General Surgery ABSITE and Board Review. Pearls of Wisdom. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-146431-4.

- ↑ Pregerson, Brady (October 1, 2006). Quick Essentials: Emergency Medicine (2nd ed.). ED Insight Books. ISBN 0-9761552-7-3.

- ↑ Aortic Coarctation Imaging at eMedicine

- ↑ Ntsinjana, Hopewell N; Hughes, Marina L; Taylor, Andrew M (2011). "The Role of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Pediatric Congenital Heart Disease". Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 13: 51. doi:10.1186/1532-429X-13-51. PMC 3210092

. PMID 21936913.

. PMID 21936913. - ↑ Radegran, Kjell (2003). "The Early History of Cardiac Surgery in Stockholm". Journal of Cardiac Surgery. 18 (6): 564–72. doi:10.1046/j.0886-0440.2003.02071.x. PMID 14992112.

- ↑ Kohl, T; Tchatcheva, K; Stressig, R; Geipel, A; Heitzer, S; Gembruch, U (2008). "Maternal hyperoxygenation in late gestation promotes rapid increase of cardiac dimensions in fetuses with hypoplastic left hearts with intrinsically normal or slightly abnormal aortic and mitral valves". Ultraschall in der Medizin. 29 (S 2). doi:10.1055/s-2008-1080778.

- ↑ {http://www.ctsnet.org/article/ligation-thoracic-duct-chylothorax}

- ↑ Mathew, Thomas; Idhrees, Mohammed; Misra, Satyajeet; Menon, Sabarinath; Dharan, Baiju Sasi; Karunakaran, Jayakumar (May 2015). "Intraoperative Identification of Chyle Leak During Coarctation Repair Using Fluorescein Dye". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 99 (5): 1827. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.12.090. PMID 25952224.

- ↑ Beekman, Robert H.; Rocchini, Albert P.; Behrendt, Douglas M.; Bove, Edward L.; Dick, Macdonald; Crowley, Dennis C.; Rebecca Snider, A.; Rosenthal, Amnon (1986). "Long-term outcome after repair of coarctation in infancy: Subclavian angioplasty does not reduce the need for reoperation". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 8 (6): 1406–11. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80314-x. PMID 2946743.

- ↑ Cohen, M.; Fuster, V.; Steele, P. M.; Driscoll, D.; McGoon, D. C. (1989). "Coarctation of the aorta. Long-term follow-up and prediction of outcome after surgical correction". Circulation. 80 (4): 840–5. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.80.4.840. PMID 2791247.

- ↑ Di Salvo, G; Castaldi, B; Baldini, L; Gala, S; del Gaizo, F; D'Andrea, A; Limongelli, G; D'Aiello, A F; Scognamiglio, G; Sarubbi, B; Pacileo, G; Russo, M G; Calabrò, R (2011). "Masked hypertension in young patients after successful aortic coarctation repair: impact on left ventricular geometry and function". Journal of Human Hypertension. 25 (12): 739–45. doi:10.1038/jhh.2010.118. PMID 21228825.

- 1 2 Giuffre, Michael; Ryerson, Lindsay; Chapple, Denise; Crawford, Susan; Harder, Joyce; Leung, Alexander K. C. (2005). "Nonductal dependent coarctation: a 20-year study of morbidity and mortality comparing early-to-late surgical repair". Journal of the National Medical Association. 97 (3): 352–6. PMC 2568624

. PMID 15779499.

. PMID 15779499. - ↑ Celermajer, DS; Greaves, K (2002). "Survivors of coarctation repair: fixed but not cured". Heart. 88 (2): 113–4. doi:10.1136/heart.88.2.113. PMC 1767208

. PMID 12117824.

. PMID 12117824.

Further reading

- Toro-Salazar, Olga H; Steinberger, Julia; Thomas, William; Rocchini, Albert P; Carpenter, Becky; Moller, James H (2002). "Long-term follow-up of patients after coarctation of the aorta repair". The American Journal of Cardiology. 89 (5): 541–7. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(01)02293-7. PMID 11867038.

- Brouwer, Rene M.H.J.; Erasmus, Michiel E.; Ebels, Tjark; Eijgelaar, Anton (1994). "Influence of age on survival, late hypertension, and recoarctation in elective aortic coarctation repair. Including long-term results after elective aortic coarctation repair with a follow-up from 25 to 44 years". The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 108 (3): 525–31. doi:10.1016/S0022-5223(94)70264-0 (inactive August 6, 2015). PMID 8078345.

- Jenkins, N.P. (1999). "Coarctation of the aorta: natural history and outcome after surgical treatment". QJM. 92 (7): 365–71. doi:10.1093/qjmed/92.7.365. PMID 10627885.

External links

- Coarctation of the Aorta - Stanford Children's Health

- Aortic Coarctation information from Seattle Children's Hospital Heart Center

- Diagram at kumc.edu

- Overview and diagram at umich.edu

- 3D CT Angiogram Radiology of Coarctation

- "Coarctation of the aorta". Mayo Clinic. April 20, 2012.

- "Cardiac Catheterization". Cleveland Clinic. September 2013.