Circulating microvesicle

Circulating microvesicles (cMVs) are small membrane bound fragments of between 50 and 1,000 nanometers (nm) in diameter, found in many types of body fluids as well as the interstitial space between cells. Though initially dismissed as cellular debris, cMVs have a role in cell signaling and the process of molecular communication between cells, and are released by a number of cell types.[1] Although a consistent and precise definition is lacking, cMVs are generally considered to be a heterogeneous population of exosomes (<100 nm) and shed microvesicles (100-1000 nm), which are similar but have distinct mechanisms of formation. Through these mechanisms, cMVs are released into the extracellular space and interact with specific target cells, delivering bioactive molecules. Changes in cMV levels are implicated in a variety of diseases, including cancer. These changes can be used as biomarkers in a variety of diagnostic assays.

Formation and contents

Process of formation

Microvesicles and exosomes are formed and released by two slightly different mechanisms. These processes result in the release of intercellular signaling vesicles. Microvesicles are small, plasma membrane-derived particles that are released into the extracellular environment by the outward budding and fission of the plasma membrane. This budding process involves multiple signaling pathways including the elevation of intracellular calcium and reorganization of the cell's structural scaffolding. The formation and release of microvesicles involve contractile machinery that draws opposing membranes together before pinching off the membrane connection and launching the vesicle into the extracellular space.[2][3][4]

Microvesicle budding takes place at unique locations on the cell membrane that are enriched with specific lipids and proteins reflecting their cellular origin. At these locations, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids are selectively incorporated into microvesicles and released into the surrounding environment.[3]

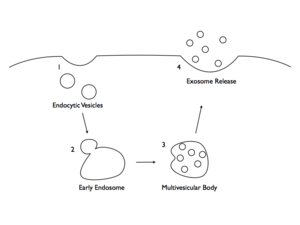

Exosomes are membrane-covered vesicles, formed intracellularly are considered to be smaller than 100 nm. In contrast to microvesicles, which are formed through a process of membrane budding, or exocytosis, exosomes are initially formed by endocytosis. Exosomes are formed by invagination within a cell to create an intracellular vesicle called an endosome, or an endocytic vesicle. In general, exosomes are formed by segregating the cargo (e.g., lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids) within the endosome. Once formed, the endosome combines with a structure known as a multivesicular body (MVB). The MVB containing segregated endosomes ultimately fuses with the plasma membrane, resulting in exocytosis of the exosomes.[4][5]

Once formed, both microvesicles and exosomes (collectively called cMVs) circulate in the extracellular space near the site of release, where they can be taken up by other cells or gradually deteriorate. In addition, some vesicles migrate significant distances by diffusion, ultimately appearing in biological fluids such as cerebrospinal fluid, blood, and urine.[4]

Molecular contents

The lipid and protein content of cMVs have been analyzed using various biochemical techniques. cMVs display a spectrum of molecules enclosed within the vesicles and their plasma membranes. Both the membrane molecular pattern and the internal contents of the vesicle depend on the cellular origin and the molecular processes triggering their formation. Because cMVs are not intact cells, they do not contain mitochondria, Golgi, endoplasmic reticulum, or a nucleus with its associated DNA.[5][6]

cMV membranes consist mainly of lipids and proteins. Regardless of their cell type of origin, nearly all cMVs contain proteins involved in membrane transport and fusion. They are surrounded by a phospholipid bilayer composed of several different lipid molecules. The protein content of each cMV reflects the origin of the cell from which it was released. For example, those released from antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as B cells and dendritic cells, are enriched in proteins necessary for adaptive immunity, while cMVs released from tumors contain proapoptotic molecules and oncogenic receptors (e.g. EGFR).[5]

In addition to the proteins specific to the cell type of origin, some proteins are common to most cMVs. For example, nearly all contain the cytoplasmic proteins tubulin, actin and actin-binding proteins, as well as many proteins involved in signal transduction, cell structure and motility, and transcription. Most cMVs contain the so-called "heat-shock proteins" hsp70 and hsp90, which can facilitate interactions with cells of the immune system. Finally, tetraspanin proteins, including CD9, CD37, CD63 and CD81 are one of the most abundant protein families found in cMV membranes.[5][6][7][8] Many of these proteins may be involved in the sorting and selection of specific cargos to be loaded into the lumen of the cMV or its membrane.[9]

Other than lipids and proteins, cMVs are enriched with nucleic acids (e.g., messenger RNA (mRNA) and microRNA (miRNA). The identification of RNA molecules in cMVs supports the hypothesis that they are a biological vehicle for the transfer of nucleic acids and subsequently modulate the target cell's protein synthesis. Messenger RNA transported from one cell to another through cMVs can be translated into proteins, conferring new function to the target cell. The discovery that cMVs may shuttle specific mRNA and miRNA suggests that this may be a new mechanism of genetic exchange between cells.[8][10] Exosomes produced by cells exposed to oxidative stress can mediate protective signals, reducing oxidative stress in recipient cells, a process which is proposed to depend on exosomal RNA transfer.[11] These RNAs are specifically targeted to cMVs, in some cases containing detectable levels of RNA that is not found in significant amounts in the donor cell.[8]

Because the specific proteins, mRNAs, and miRNAs in CMVs are highly variable, it is likely that these molecules are specifically packaged into vesicles using an active sorting mechanism. At this point, it is unclear exactly which mechanisms are involved in packaging soluble proteins and nucleic acids into cMVs.[3][12]

Role on target cells

Once released from their cell of origin, cMVs interact specifically with cells they recognize by binding to cell-type specific, membrane-bound receptors. Because cMVs contain a variety of surface molecules, they provide a mechanism for engaging different cell receptors and exchanging material between cells. This interaction ultimately leads to fusion with the target cell and release of the vesicles' components, thereby transferring bioactive molecules, lipids, genetic material, and proteins. The transfer of cMV components includes specific mRNAs and proteins, contributing to the proteomic properties of target cells.[8] cMVs can also transfer miRNAs that are known to regulate gene expression by altering mRNA turnover.[3][4][6][13]

Mechanisms of signaling

Degradation

In some cases, the degradation of cMVs are necessary for the release of signaling molecules. During cMV production, the cell can concentrate and sort the signaling molecules which are released into the extracellular space upon cMV degradation. Dendritic cells, macrophage and microglia derived cMVs contain proinflammatory cytokines and neurons and endothelial cells release growth factors using this mechanism of release.[4]

Fusion

Proteins on the surface of the cMV will interact with specific molecules, such as integrin, on the surface of its target cell. Upon binding, the cMV can fuse with the plasma membrane. This results in the delivery of nucleotides and soluble proteins into the cytosol of the target cell as well as the integration of lipids and membrane proteins into its plasma membrane.[1]

Internalization

cMV can be endocytosed upon binding to their targets, allowing for additional steps of regulation by the target cell. The cMV may fuse, integrating lipids and membrane proteins into the endosome while releasing its contents into the cytoplasm. Alternatively, the endosome may mature into a lysosome causing the degradation of the cMV and its contents, in which case the signal is ignored.[1]

Transcytosis

After internalization of cMV via endocytosis, the endosome may move across the cell and fuse with the plasma membrane, a process called transcytosis. This results in the ejection of the cMV back into the extracellular space or may result in the transportation of the cMV into a neighboring cell.[1] This mechanism might explain the ability of cMV to cross biological barriers, such as the blood brain barrier, by moving from cell to cell.[14]

Contact dependent signaling

In this form of signaling, the cMV does not fuse with the plasma membrane or engulfed by the target cell. Similar to the other mechanisms of signaling, the cMV has molecules on its surface that will interact specifically with its target cell. There are additional surface molecules, however, that can interact with receptor molecules which will interact with various signaling pathways.[4] This mechanism of action can be used in processes such as antigen presentation, where MHC molecules on the surface of cMV can stimulate an immune response.[9] Alternatively, there may be molecules on cMV surfaces that can recruit other proteins to form extracellular protein complexes that may be involved in signaling to the target cell.[4]

Relevance in disease

Cancer

Promoting aggressive tumor phenotypes

The oncogenic receptor ECGFvIII, which is located in a specific type of aggressive glioma tumor, can be transferred to a non-aggressive population of tumor cells via cMVs. After the oncogenic protein is transferred, the recipient cells become transformed and show characteristic changes in the expression levels of target genes. It is possible that transfer of other mutant oncogenes, such as HER2, may be a general mechanism by which malignant cells cause cancer growth at distant sites.[3][13] cMVs from non-cancer cells can signal to cancer cells to become more aggressive. Upon exposure to cMVs from tumor-associated macrophages, breast cancer cells become more invasive in vitro.[15]

Promoting angiogenesis

Angiogenesis, which is essential for tumor survival and growth, occurs when endothelial cells proliferate to create a matrix of blood vessels that infiltrate the tumor, supplying the nutrients and oxygen necessary for tumor growth. A number of reports have demonstrated that tumor-associated cMVs release proangiogenic factors that promote endothelial cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. cMVs shed by tumor cells and taken up by endothelial cells also facilitate angiogenic effects by transferring specific mRNAs and miRNAs.[4]

Involvement in multidrug resistance

When anticancer drugs such as doxorubicin accumulate in cMVs, the drug's cellular levels decrease. This can ultimately contribute to the process of drug resistance. Similar processes have been demonstrated in cMVs released from cisplatin-insensitive cancer cells. Vesicles from these tumors contained nearly three times more cisplatin than those released from cisplatin-sensitive cells. For example, tumor cells can accumulate drugs into cMVs. Subsequently, the drug-containing cMVs are released from the cell into the extracellular environment, thereby mediating resistance to chemotherapeutic agents and resulting in significantly increased tumor growth, survival, and metastasis.[3][16]

Interference with antitumor immunity

cMVs from various tumor types can express specific cell-surface molecules (e.g. FasL or CD95) that induce T-cell apoptosis and reduce the effectiveness of other immune cells. cMVs released from lymphoblastoma cells express the immune-suppressing protein latent membrane protein-1 (LMP-1), which inhibits T-cell proliferation and prevents the removal of circulating tumor cells (CTCs). As a consequence, tumor cells can turn off T-cell responses or eliminate the antitumor immune cells altogether by releasing cMVs.[3]

Impact on tumor metastasis

Degradation of the extracellular matrix is a critical step in promoting tumor growth and metastasis. Tumor-derived cMVs often carry protein-degrading enzymes, including matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2), MMP-9, and urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA). By releasing these proteases, tumor cells can degrade the extracellular matrix and invade surrounding tissues. Likewise, inhibiting MMP-2, MMP-9, and uPA prevents cMVs from facilitating tumor metastasis. Matrix digestion can also facilitate angiogenesis, which is important for tumor growth and is induced by the horizontal transfer of RNAs from microvesicles.[3]

Other disease states

The release of cMVs has been shown from endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, platelets, white blood cells (e.g. leukocytes and lymphocytes), and red blood cells. Although some of these cMV populations occur in the blood of healthy individuals and patients, there are obvious changes in number, cellular origin, and composition in various disease states.[17][18] It has become clear that cMVs play important roles in regulating the cellular processes that lead to disease pathogenesis. Moreover, because cMVs are released following apoptosis or cell activation, they have the potential to induce or amplify disease processes. Some of the inflammatory and pathological conditions that cMVs are involved in include cardiovascular disease, hypertension, neurodegenerative disorders, diabetes, and rheumatic diseases.[4][5]

Vascular diseases

Circulating microvesicles isolated from cardiac surgery patients were found to be thrombogenic in both in vitro assays and in rats. Microvesicles isolated from healthy individuals did not have the same effects and may actually have a role in reducing clotting.[19][20] Tissue factor, an initiator of coagulation, is found in high levels within microvesicles, indicating their role in clotting.[21] Additionally, microvesicles can induce clotting by binding to clotting factors or by inducing the expression of clotting factors in other cells.[20] cMVs and tissue factor are associated with diabetic vasculopathy in a mechanism affected by hyperglycemia in diabetic patients. Renal mesangial cells exposed to high glucose media release cMVs containing tissue factor, having an angiogenic effect on endothelial cells.[22] Atherosclerosis has also been linked with circulating microvesicles originating from platelets and macrophages. These cMVs are found in high levels within atherosclerotic plaques, and their presence results in communication with clotting machinery that exacerbates the condition.[4]

Inflammation

Microvesicles contain cytokines that can induce inflammation via numerous different pathways.[20] These cells will then release more microvesicles, which have an additive effect. This can call neutrophils and leukocytes to the area, resulting in the aggregation of cells.[1][23] However, microvesicles also seem to be involved in a normal physiological response to disease, as there are increased levels of microvesicles that result from pathology.[20]

Neurological disorders

Microvesicles seem to be involved in a number of neurological diseases. Since they are involved in numerous vascular diseases and inflammation, strokes and multiple sclerosis seem to be other diseases for which microvesicles are involved. Circulating microvesicles seem to have an increased level of phosphorylated tau proteins during early stage Alzheimer's disease. Similarly, increased levels of CD133 are an indicator of epilepsy.[24]

Clinical applications

Detection of cancer

Tumor-associated cMVs are abundant in the blood, urine, and other body fluids of patients with cancer, and are likely involved in tumor progression. They offer a unique opportunity to noninvasively access the wealth of biological information related to their cells of origin. The quantity and molecular composition of cMVs released from malignant cells varies considerably compared with those released from normal cells. Thus, the concentration of plasma cMVs with molecular markers indicative of the disease state may be used as an informative blood-based biosignature for cancer.[2] cMVs express many membrane-bound proteins, some of which can be used as tumor biomarkers. Several tumor markers accessible as proteins in blood or urine have been used to screen and diagnose various types of cancer. In general, tumor markers are produced either by the tumor itself or by the body in response to the presence of cancer or some inflammatory conditions. If a tumor marker level is higher than normal, the patient is examined more closely to look for cancer or other conditions. For example, CA19-9, CA-125, and CEA have been used to help diagnose pancreatic, ovarian, and gastrointestinal malignancies, respectively. However, although they have proven clinical utility, none of these tumor markers are highly sensitive or specific. Clinical research data suggest that tumor-specific markers exposed on cMVs are useful as a clinical tool to diagnose and monitor disease. Research is also ongoing to determine if tumor-specific markers exposed on cMVs are predictive for therapeutic response.[25][26][27][28]

Biological markers for disease

In addition to detecting cancer, it is possible to use microvesicles as biological markers to give prognoses for various diseases. Many types of neurological diseases are associated with increased level of specific types of circulating microvesicles. For example, elevated levels of phosphorylated tau proteins can be used to diagnose patients in early stages of Alzheimer's. Additionally, it is possible to detect increased levels of CD133 in microvesicles of patients with epilepsy.[24]

Mechanism for drug delivery

Circulating microvesicles may be useful for the delivery of drugs to very specific targets. Using electroporation or centrifugation to insert drugs into microvesicles targeting specific cells, it is possible to target the drug very efficiently.[14] This targeting can help by reducing necessary doses as well as prevent off-target side effects. They can target anti-inflammatory drugs to specific tissues.[23] Additionally, circulating microvesicles can bypass the blood–brain barrier and deliver their cargo to neurons while not having an effect on muscle cells. The blood-brain barrier is typically a difficult obstacle to overcome when designing drugs, and microvesicles may be a means of overcoming it.[14] Current research is looking into efficiently creating microvesicles synthetically, or isolating them from patient or engineered cell lines.[29]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Camussi, G; Deregibus, MC; Bruno, S; Cantaluppi, V; Biancone, L (November 2010). "Exosomes/microvesicles as a mechanism of cell-to-cell communication.". Kidney International. 78 (9): 838–48. doi:10.1038/ki.2010.278. PMID 20703216.

- 1 2 Van Doormaal, FF; Kleinjan, A; Di Nisio, M; Büller, HR; Nieuwland, R (2009). "Cell-derived microvesicles and cancer". The Netherlands journal of medicine. 67 (7): 266–73. PMID 19687520.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Muralidharan-Chari, V.; Clancy, J. W.; Sedgwick, A.; D'souza-Schorey, C. (2010). "Microvesicles: mediators of extracellular communication during cancer progression". Journal of Cell Science. 123 (Pt 10): 1603–11. doi:10.1242/jcs.064386. PMC 2864708

. PMID 20445011.

. PMID 20445011. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Cocucci, Emanuele; Racchetti, Gabriella; Meldolesi, Jacopo (2009). "Shedding microvesicles: artefacts no more". Trends in Cell Biology. 19 (2): 43–51. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2008.11.003. PMID 19144520.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pap, E.; Pállinger, É.; Pásztói, M.; Falus, A. (2009). "Highlights of a new type of intercellular communication: microvesicle-based information transfer". Inflammation Research. 58 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1007/s00011-008-8210-7. PMID 19132498.

- 1 2 3 Schorey, Jeffrey S.; Bhatnagar, Sanchita (2008). "Exosome Function: From Tumor Immunology to Pathogen Biology". Traffic. 9 (6): 871–81. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00734.x. PMID 18331451.

- ↑ Simpson, Richard J.; Jensen, Søren S.; Lim, Justin W. E. (2008). "Proteomic profiling of exosomes: Current perspectives". Proteomics. 8 (19): 4083–99. doi:10.1002/pmic.200800109. PMID 18780348.

- 1 2 3 4 Valadi, Hadi; Ekström, Karin; Bossios, Apostolos; Sjöstrand, Margareta; Lee, James J; Lötvall, Jan O (2007). "Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells". Nature Cell Biology. 9 (6): 654–9. doi:10.1038/ncb1596. PMID 17486113.

- 1 2 Raposo, G; Stoorvogel, W (Feb 18, 2013). "Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends.". The Journal of Cell Biology. 200 (4): 373–83. doi:10.1083/jcb.201211138. PMID 23420871.

- ↑ Lewin, Alfred; Yuan, Alex; Farber, Erica L.; Rapoport, Ana Lia; Tejada, Desiree; Deniskin, Roman; Akhmedov, Novrouz B.; Farber, Debora B. (2009). Lewin, Alfred, ed. "Transfer of MicroRNAs by Embryonic Stem Cell Microvesicles". PLoS ONE. 4 (3): e4722. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004722. PMC 2648987

. PMID 19266099.

. PMID 19266099. - ↑ Eldh M, Ekström K, Valadi H, Sjöstrand M, Olsson B, Jernås M, Lötvall J. Exosomes Communicate Protective Messages during Oxidative Stress; Possible Role of Exosomal Shuttle RNA. PLoS One. 2010 Dec 17;5(12):e15353.

- ↑ Simons, Mikael; Raposo, Graça (2009). "Exosomes – vesicular carriers for intercellular communication". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 21 (4): 575–81. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2009.03.007. PMID 19442504.

- 1 2 Ratajczak, J; Miekus, K; Kucia, M; Zhang, J; Reca, R; Dvorak, P; Ratajczak, M Z (2006). "Embryonic stem cell-derived microvesicles reprogram hematopoietic progenitors: evidence for horizontal transfer of mRNA and protein delivery". Leukemia. 20 (5): 847–56. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2404132. PMID 16453000.

- 1 2 3 Lakhal, S; Wood, MJ (October 2011). "Exosome nanotechnology: an emerging paradigm shift in drug delivery: exploitation of exosome nanovesicles for systemic in vivo delivery of RNAi heralds new horizons for drug delivery across biological barriers.". BioEssays. 33 (10): 737–41. doi:10.1002/bies.201100076. PMID 21932222.

- ↑ Yang, M; Chen, J; Su, F; Yu, B; Su, F; Lin, L; Liu, Y; Huang, JD; Song, E (Sep 22, 2011). "Microvesicles secreted by macrophages shuttle invasion-potentiating microRNAs into breast cancer cells". Molecular cancer. 10: 117. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-10-117. PMC 3190352

. PMID 21939504.

. PMID 21939504. - ↑ Shedden, Kerby; Xie, Xue Tao; Chandaroy, Parthapratim; Chang, Young Tae; Rosania, Gustavo R. (2003). "Expulsion of small molecules in vesicles shed by cancer cells: association with gene expression and chemosensitivity profiles". Cancer Research. 63 (15): 4331–7. PMID 12907600.

- ↑ Nieuwland, R (2012). Platelet-Derived Microparticles. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. pp. 453–67. ISBN 978-0123878373.

- ↑ Vanwijk, M; Vanbavel, E; Sturk, A; Nieuwland, R (2003). "Microparticles in cardiovascular diseases". Cardiovascular Research. 59 (2): 277–87. doi:10.1016/S0008-6363(03)00367-5. PMID 12909311.

- ↑ Biró, E; Sturk-Maquelin, KN; Vogel, GM; Meuleman, DG; Smit, MJ; Hack, CE; Sturk, A; Nieuwland, R (December 2003). "Human cell-derived microparticles promote thrombus formation in vivo in a tissue factor-dependent manner.". Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 1 (12): 2561–8. doi:10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00456.x. PMID 14738565.

- 1 2 3 4 Distler, JH; Pisetsky, DS; Huber, LC; Kalden, JR; Gay, S; Distler, O (November 2005). "Microparticles as regulators of inflammation: novel players of cellular crosstalk in the rheumatic diseases.". Arthritis and rheumatism. 52 (11): 3337–48. doi:10.1002/art.21350. PMID 16255015.

- ↑ Müller, I; Klocke, A; Alex, M; Kotzsch, M; Luther, T; Morgenstern, E; Zieseniss, S; Zahler, S; Preissner, K; Engelmann, B (March 2003). "Intravascular tissue factor initiates coagulation via circulating microvesicles and platelets.". FASEB Journal. 17 (3): 476–78. doi:10.1096/fj.02-0574fje. PMID 12514112.

- ↑ Shai, E; Varon, D (January 2011). "Development, cell differentiation, angiogenesis--microparticles and their roles in angiogenesis.". Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 31 (1): 10–4. doi:10.1161/atvbaha.109.200980. PMID 21160063.

- 1 2 Sun, D; Zhuang, X; Xiang, X; Liu, Y; Zhang, S; Liu, C; Barnes, S; Grizzle, W; Miller, D; Zhang, HG (September 2010). "A novel nanoparticle drug delivery system: the anti-inflammatory activity of curcumin is enhanced when encapsulated in exosomes.". Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 18 (9): 1606–14. doi:10.1038/mt.2010.105. PMID 20571541.

- 1 2 Colombo, E; Borgiani, B; Verderio, C; Furlan, R (2012). "Microvesicles: novel biomarkers for neurological disorders". Frontiers in Physiology. 3: 63. doi:10.3389/fphys.2012.00063. PMC 3315111

. PMID 22479250.

. PMID 22479250. - ↑ Larkin, Samantha ET; Zeidan, Bashar; Taylor, Matthew G; Bickers, Bridget; Al-Ruwaili, Jamal; Aukim-Hastie, Claire; Townsend, Paul A (2010). "Proteomics in prostate cancer biomarker discovery". Expert Review of Proteomics. 7 (1): 93–102. doi:10.1586/epr.09.89. PMID 20121479.

- ↑ Pawlowski, Traci L.; Spetzler, David; Tinder, Teresa; Esmay, Paula; Conrad, Amber; Ellis, Phil; Kennedy, Patrick; Tyrell, Annemarie; et al. (April 20, 2010). Identifying and characterizing subpopulation of exosomes to provide the foundation for a novel exosome-based cancer diagnostic platform. Proceedings of the 101st Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

- ↑ Kuslich, Christine; Pawlowski, Traci L.; Deng, Ta; Tinder, Teresa; Kim, Joon; Kimbrough, Jeff; Spetzler, David (2010). A Sensitive exosome-based biosignature for the diagnosis of prostate cancer (PDF). Proceedings of the 2010 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. Also published as Kuslich, Christine; Pawlowski, Traci L.; Deng, Ta; Tinder, Teresa; Kim, Joon; Kimbrough, Jeff; Spetzler, David (May 2010). "A sensitive exosome-based biosignature for the diagnosis of prostate cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 28 (15 suppl): 4636.

- ↑ Kuslich, Christine; Pawlowski, Traci; Kimbrough, Jeff; Deng, Ta; Tinder, Teresa; Kim, Joon; Spetzler, David (April 18, 2010). Plasma exosomes are a robust biosignature for prostate cancer. Proceedings of the 101st Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research. Also published as Kuslich, Christine; Pawlowski, Traci; Kimbrough, Jeff; Deng, Ta; Tinder, Teresa; Kim, Joon; Spetzler, David (2010). "Circulating exosomes are a robust biosignature for prostate cancer" (PDF). Caris Life Sciences.

- ↑ http://cordis.europa.eu/search/index.cfm?fuseaction=proj.document&PJ_RCN=11624184. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

Further reading

- Nilsson, J; Skog, J; Nordstrand, A; Baranov, V; Mincheva-Nilsson, L; Breakefield, X O; Widmark, A (2009). "Prostate cancer-derived urine exosomes: a novel approach to biomarkers for prostate cancer". British Journal of Cancer. 100 (10): 1–5. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605058. PMC 2696767

. PMID 19401683.

. PMID 19401683. - Al-Nedawi, Khalid; Meehan, Brian; Rak, Janusz (2009). "Microvesicles: messengers and mediators of tumor progression". Cell cycle. 8 (13): 2014–8. doi:10.4161/cc.8.13.8988. PMID 19535896.